NANTAI NVERSTES HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY ktisadi dari ve Sosyal

- Slides: 32

NİŞANTAŞI ÜNİVERSİTESİ HEALTH PSYCHOLOGY İktisadi, İdari ve Sosyal Bilimler Fakültesi iisbf. nisantasi. edu. tr NİŞANTAŞI ÜNİVERSİTESİ ©

LEARNING OUTCOMES By the end of this chapter, you should have an understanding of: • the physical and emotional impact of illness • the diverse nature of coping responses in the face of illness • demographic, clinical and psychosocial influences on patient outcomes • Qo. L as a multidimensional, dynamic and subjective construct • typical models of patient adjustment to illness • challenges to assessing subjective health status and quality of life

THE ILLNESS PROCESS Individuals facing illness have to deal with: Uncertainty: try to understand the meaning and severity of the first symptoms. Disruption: becomes evident that they have a significant illness. Experience a crisis characterised by intense stress and a high level of dependence on health professionals and/or other people who are emotionally close to the individual. Striving for recovery: attempt to gain some form of control over their illness by means of active coping. Restoration of well-being: achieve a new emotional equilibrium based on an acceptance of the illness and its consequences.

RESPONSES TO CANCER DIAGNOSIS (HOLLAND GOOEN-PIELS 2000) Initial response: can include disbelief, denial and shock. Some people may challenge the diagnosis or the ability of the health professional. Individuals may not process information clearly. Dysphoria: gradually (1– 2 weeks) come to terms with the reality of their diagnosis. Simultaneously, they may experience significant distress, insomnia, reduced appetite, poor concentration, anxiety and depression. Hope and optimism may also emerge. Adaptation: may last for weeks or months, and involves the person adapting more positively to their diagnosis and developing long-term coping strategies in order to maintain equilibrium. NB: Not all people will (a) move through the stages or (b) achieve adaptation.

ILLNESS AND PHYSICAL OUTCOMES Fatigue is common in many chronic conditions and within many is associated with anxiety and depression: • Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (Wearden et al. 2012) • cancer (Brown and Kroenke, 2009) • lung disease, diabetes CHD and rheumatoid arthritis (Katon et al. 2007) Fatigue is consistently associated with impaired Qo. L. Immune changes are provoked from acute stress • e. g. reduced NK cell or slowed wound healing • Those with acute pain or undergoing surgery report immune changes of a similar nature (Graham et al. 2006). Physical responses to illness have wider emotional and social consequences.

ILLNESS AND NEGATIVE EMOTIONS Reactions to diagnosis emotional reactions to a cancer diagnosis are frequently catastrophic and highly emotional (Landmark and Wahl 2002); negative emotional reactions also common among those with sudden onset heart disease, stroke, chronic lower back pain, HIV infection. Reactions to illness and/or treatment include higher distress, depression and anxiety; are even higher in diseases attached to stigma (i. e. HIV infection, AIDS); are contributed by a sense of loss (i. e. of control, independence, self, etc. ); can be caused by side effects e. g. cancer chemotherapy and distress; are elevated at certain points during treatment e. g. first and last treatment. Reactions at the end of treatment emotional ambivalence; perceived health-care professional ‘abandonment’; disappointment.

POSITIVE RESPONSES TO ILLNESS Positive appraisals – e. g. optimism: • Positive appraisals consistently associated with positive outcomes either directly, or indirectly via effects on coping. Positive emotions (Fredrickson 1998, 2001): • promote psychological resilience and more effective problem -solving; • dispel negative emotions; • trigger an upward spiral of positive feelings; • improve functional recovery (Fredman et al. 2006).

FINDING BENEFIT Five domains of positive change as a result of stress or trauma have generally been identified: • enhanced personal relationships; • greater appreciation for life; • a sense of increased personal strength; • greater spirituality; • a valued change in life priorities and goals. (Tedeschi and Calhoun 2004; Calhoun and Tedeschi 2007)

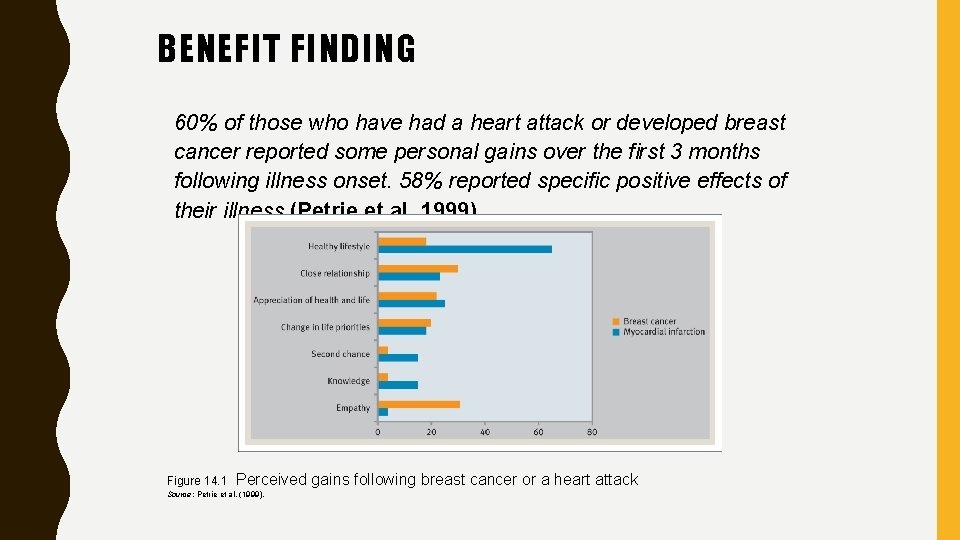

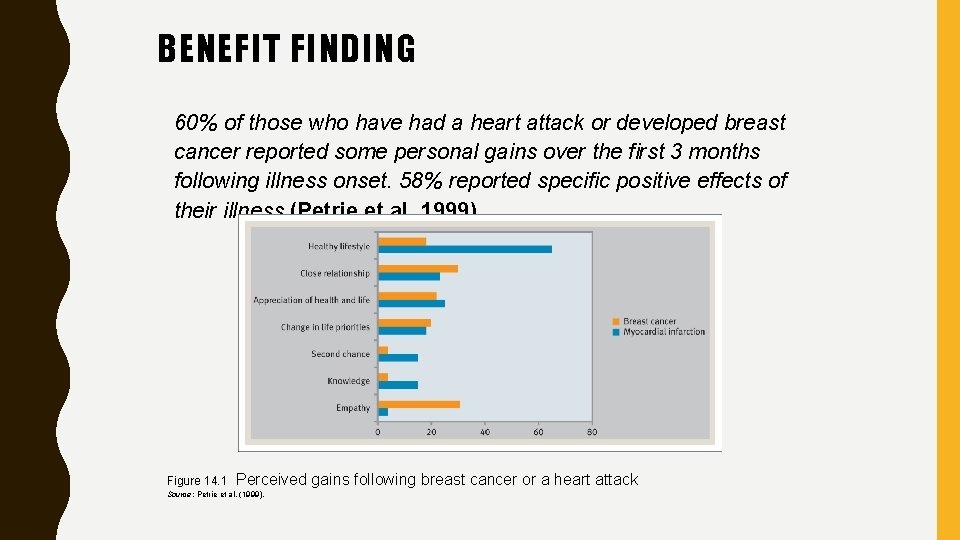

BENEFIT FINDING 60% of those who have had a heart attack or developed breast cancer reported some personal gains over the first 3 months following illness onset. 58% reported specific positive effects of their illness (Petrie et al. 1999). Figure 14. 1 Perceived gains following breast cancer or a heart attack Source: Petrie et al. (1999).

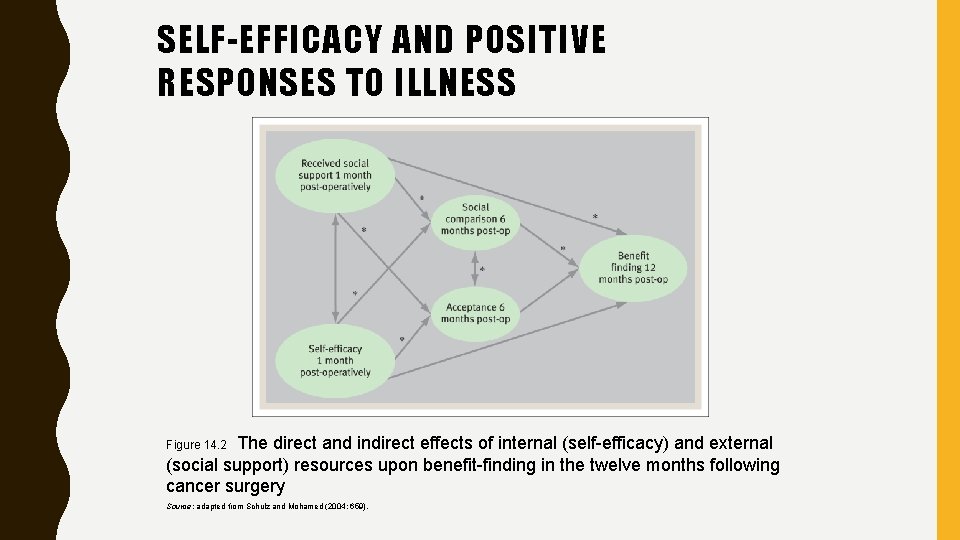

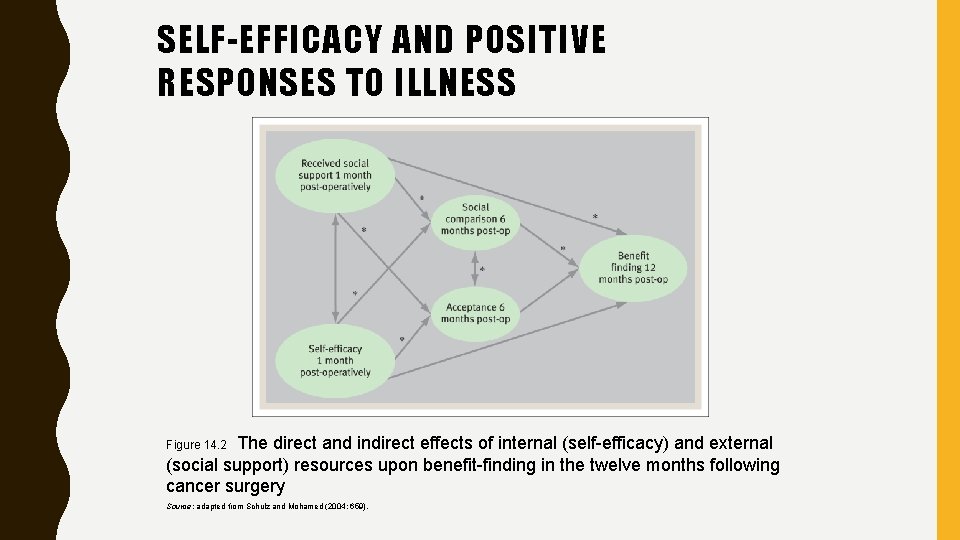

SELF-EFFICACY AND POSITIVE RESPONSES TO ILLNESS The direct and indirect effects of internal (self-efficacy) and external (social support) resources upon benefit-finding in the twelve months following cancer surgery Figure 14. 2 Source: adapted from Schulz and Mohamed (2004: 659).

CRISIS THEORY OF ILLNESS Moos and Schaefer (1984) describe the experience of illness as a ‘crisis’, whereby individuals face potential changes in: • identity (e. g. healthy person to ‘sick’ person) • location (home to hospital or nursing home) • role (e. g. from independent breadwinner to dependent) • aspects of social support (e. g. from socially integrated to socially isolated).

COPING WITH A ‘CRISIS’ Moos and Schaefer (1984) identified 3 processes resulting from an illness ‘crisis’: Cognitive appraisal: the individual appraises the implications of the illness for their lives. Adaptive tasks: the individual performs illness-specific tasks (e. g. dealing with symptoms) and general tasks (e. g. preserving emotional balance and relationships). Coping skills: the individual engages in coping strategies: • • • appraisal-focused (e. g. denial or minimising, positive reappraisal, mental preparation/planning) problem-focused (e. g. information and support-seeking, taking action to deal with a problem, identifying alternative goals and rewards) emotion-focused (e. g. mood regulation, emotional discharge such as venting anger, or passive and resigned acceptance).

ADAPTIVE TASKS IN CHRONIC DISEASE Moos and Schaefer (1984) illness-specific tasks: – dealing with symptoms of the disease and possible pain; – maintaining control over illness, such as symptom management, treatment, or prevention of progression; – managing communicative relationships with health care professionals (HCP); – facing and preparing for an uncertain future; – preserving self-image and possibly self-esteem; – maintaining control over health and life in general; – dealing with changes in relationships with family and friends.

AVOIDANT COPING AND DENIAL Many, but not all, studies report negative outcomes of such coping: Avoidant coping and emotion-focused strategies associated with greater depression than problem-focused coping among HIV positive homosexual men (Safren et al. 2002). Cognitive avoidance coping (i. e. passive acceptance, resignation) among women with breast cancer was associated with a significant risk of poor long-term psychological adjustment at a 3 year follow-up (Hack and Degner 2004). Positive adjustment predicted by seeking social support and confrontational coping; negative adjustment predicted by depressive coping among adolescents with chronic disease. Avoidance coping not a strong predictor (Meijer et al. 2002). Scoring highly on avoidance/denial positively correlated with active coping and positive outcomes among RA patients (Smith et al. 1997).

PROBLEM-FOCUSED AND ACCEPTANCE COPING These styles of coping are often associated with more positive adaptation: acceptance-focused coping (e. g. accepting things as they are, reinterpreting things in a positive light) was associated with lower levels of distress (Lowe et al. 2000), problem-focused coping associated with high levels of positive mood, and emotion-focused coping was associated with low mood (Lowe et al. 2000). Acceptance of illness: “recognizing the need to adapt to chronic illness while perceiving the abilityto tolerate the unpredictable, uncontrollable nature of the disease and handle its adverse consequences” (Evers et al. 2001, p 1027, as cited in Casier et al. 2013)

QUALITY OF LIFE Quality of Life (Qo. L): an individual’s evaluation of their overall life experience at a given time (global quality of life). Health-related Qo. L (HRQo. L): evaluations of life experience and how it is affected by disease, accidents or treatments. According to the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL) working group (1993, 1994), Qo. L is a person’s perceptions of their position in life in relation to their cultural context and the value systems of that context and their own goals, standards and expectations.

QUALITY OF LIFE (CONT. ) Qo. L is a broad concept affected by an individuals’: • • • physical health: pain, discomfort; energy/fatigue; sleep, rest; psychological health: positive feelings; self-esteem; thinking, memory, learning and concentration; bodily image and appearance; negative feelings; level of independence: activities of daily living (e. g. self-care); mobility, medication and treatment dependence; work capacity; social relationships: personal relationships; practical social support; sexual activity; environment: e. g. physical safety and security; financial resources; home environment; availability/quality of health/social care; learning opportunities; leisure participation/opportunities; spirituality, religious and personal beliefs.

What Influences Quality of Life? Many factors influence Qo. L including: – demographics: e. g. age, culture; – the condition itself: e. g. symptoms, presence or absence of pain, functional disability, neurological damage with associated motor, emotional, cognitive, sensory or communicative impairment; – treatment: e. g. availability, nature, extent, toxicity, side effects, etc. ; – psychosocial factors: e. g. emotions (anxiety, depression), coping, social context, goals and support.

AGE AND QOL: YOUNG PEOPLE Studies with children often rely on proxy measures i. e. parents rate their child’s Qo. L. One exception: Cramer et al. (1999, cited in Mc. Ewan et al. 2004). Focus groups with adolescents (11– 17 years) with epilepsy. Identified 8 subscales related to HRQo. L: • general epilepsy impact; • memory/concentration problems; • attitudes towards epilepsy; • physical functioning; • stigma; • social support; • school behaviour; • general health perceptions. Generic Qo. L may be less affected by health status than by socio-economic factors (Jirojanakul et al. 2003).

AGE AND QOL: OLDER PEOPLE The effect of age on Qo. L ratings is not inevitable; healthy ageing is possible. Important life domains among older adults: good physical functioning; relationships with others; maintaining health and social activity (e. g. Grundy and Bowling 1999). Compared to younger samples, older people are more likely to mention: independence, or the fear of losing it; becoming dependent (Bowling 1995 b). Influences on Qo. L (Blane et al. 2004): serious and limiting health problems; housing security; receipt of welfare or non-pension income; for men only – years out of work; • non-limiting chronic disease did not affect Qo. L.

CULTURE AND QOL ‘If disease, as anthropological research suggests is so very much culture-bound, how could quality of life be culture

ASPECTS OF ILLNESS AND QOL Severity of illness/extent of disability is not consistently or inevitably associated with lower HRQo. L. • disease-specific relationships need to be explored Pervasive and persistent pain is generally associated with reduced Qo. L; e. g. indicated by depression, disability, use of health care and feelings of helplessness. Cognitive impairments in, e. g. memory or attention can influence Qo. L judgements (or the ability to complete the commonly used self-report Qo. L assessments).

ASPECTS OF TREATMENT AND QOL Children undergoing intensive treatment for cancer showed poorer Qo. L than those in remission (Bijttebier et al. 2001). Comparison of 2 types of bone marrow transplant (BMT) with chemotherapy treatment alone in an adult sample found that after 1 year BMT patients had – greater fatigue; – more problems in sexual and social relationships; – greater disruption to work and leisure activities; – BMT with donations from siblings had greater negative impact on Qo. L than those receiving from unrelated donors (Watson et al. 2004). The Qo. L reported by adults who had received a BMT at approx. 11 years of age was not significantly worse than Qo. L reported by a healthy sample (Helder et al. 2004).

PSYCHOSOCIAL INFLUENCES ON QOL Emotional responses, e. g. • lower Qo. L 4 months following heart attack in those initially most depressed or anxious (Lane et al. 2000). Coping differences, e. g. • avoidance may benefit reported Qo. L in low control situations (Carver et al. 1992); • although in low control chronic situations, e. g. chronic pain, acceptance coping or positive reinterpretation and growth coping may be more adaptive (Mc. Cracken and Eccleston 2003). Social support, e. g. • consistent support for relationship between having and using social support and positive Qo. L outcomes; • does social support lead to better Qo. L or does Qo. L lead to better

GOALS AND QOL Disturbance of personal goal attainment caused by chronic illness and its consequences is likely to influence perceived Qo. L (Echteld et al. 1998). • Goal disturbance following heart surgery was an independent predictor of disease-specific Qo. L (Echteld et al. 2003). • Being unable to fulfil ‘higher order goals’ such as fulfilling duties to others, or having fun, was associated with anxiety, depression and a lower Qo. L following a heart attack (Boersma et al. 2005). Goals may indirectly affect Qo. L outcomes by altering the ‘meaning’ a person attaches to their illness (Taylor 1983).

MEASURING QUALITY OF LIFE IN CLINICAL PRACTICE Higginson and Carr (2001) suggested several reasons for Qo. L assessment: Measure to inform: to increase understanding about the multidimensional impact of illness and factors that moderate impact to (a) inform interventions and (b) inform patients. Measure to evaluate alternatives: as a form of clinical ‘audit’ to identify which interventions have the ‘best’ outcomes – for the patient, but also in terms of costs (related concept – Quality Adjusted Life Years (QALY)), effects and patient age. Measure to promote communication: unlikely to be the primary motive for Qo. L assessment in a clinical setting. Engaging patients in Qo. L assessment so health professionals can address areas that they may not have addressed.

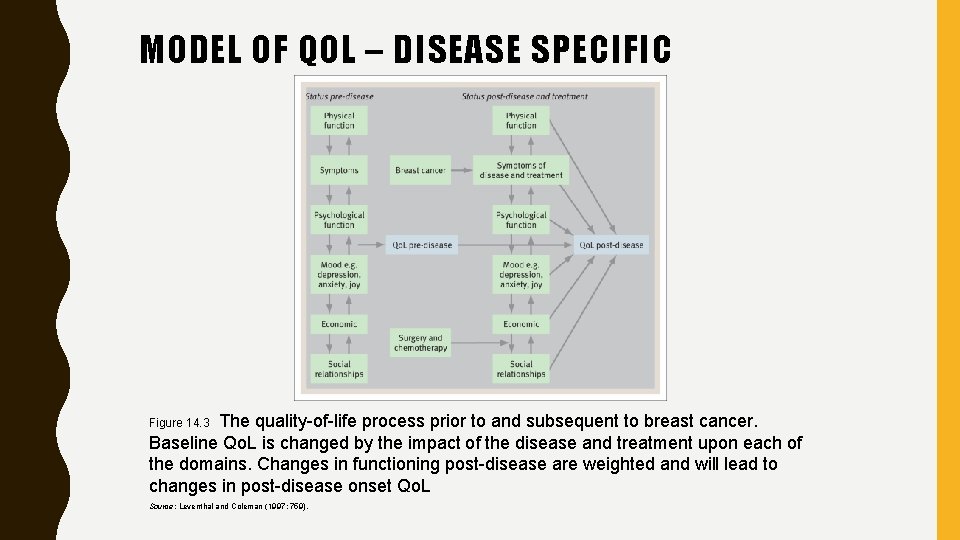

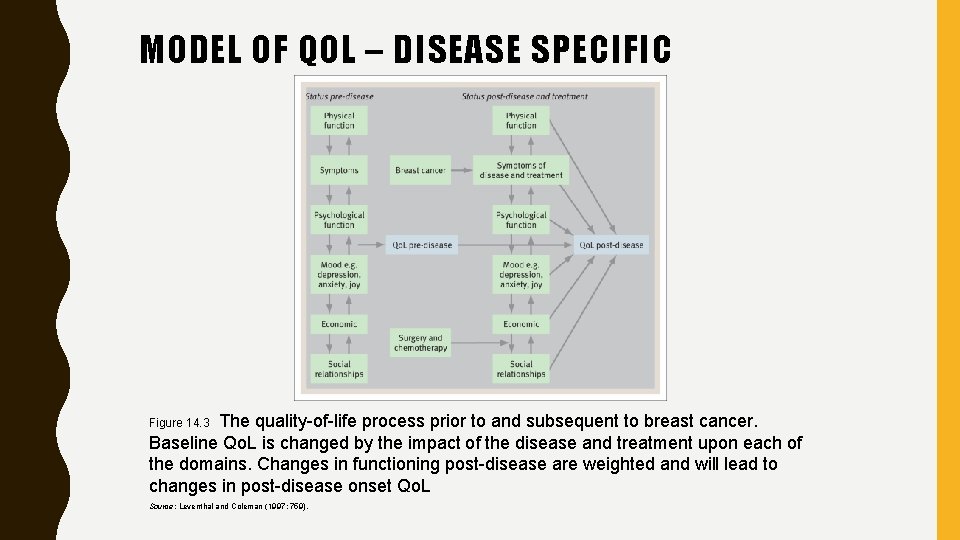

MODEL OF QOL – DISEASE SPECIFIC The quality-of-life process prior to and subsequent to breast cancer. Baseline Qo. L is changed by the impact of the disease and treatment upon each of the domains. Changes in functioning post-disease are weighted and will lead to changes in post-disease onset Qo. L Figure 14. 3 Source: Leventhal and Coleman (1997: 759).

GENERIC VS. SPECIFIC QOL MEASURES Disadvantages and advantages to both types: Generic measures (e. g. SF 36, SF 12, NHP, EUROQOL, WHOQOL) allow for comparison between different illness groups, but often fail to address some of the unique Qo. L issues for that illness. Disease-specific measures (e. g. EORTC QLQ-C 30, FACT-G, AIMS, WHOQOL-HIV) have ‘added value’ in addressing disease-specific issues, but do not allow for the same amount of cross-illness comparability.

INDIVIDUALISED QOL MEASURES Individual Qo. L instruments abandon the dimensions of many generic and disease-specific instruments and allow respondents to choose the dimensions and concerns relevant and of value to them. This ‘idiographic’ approach is adopted by: Schedule for the Evaluation of Individual Quality of Life (SEIQo. L; O’Boyle et al. 1993; Joyce et al. 2003): • invites individuals to identify 5 aspects of life that are important to them; • individuals then rate their current level of functioning on each, attach a weighting of importance to each aspect, and rate how satisfied they are with that aspect of life currently. Such methods are extremely informative but are also time consuming and complex.

ISSUES IN QOL MEASUREMENT Factors to be considered include the following: • which method of measurement; • which measure(s); • the practicality of chosen method and measures in the relevant setting (e. g. in clinics, schools, etc. ); • response shift (due to the changing course of many illnesses and treatments); • relevance to study populations’ culture and age; • assessment frequency (given potential for change).

RESPONSE SHIFT Illness can cause individuals to recalibrate their internal standards, reprioritise expectations and life values (Schwartz et al. 2004). Yardley and Dibb (2007) • Longitudinal study of 301 Meniere’s disease patients ‒ T 1: current Qo. L (SF 36) ‒ T 2 (+10 mth): current Qo. L AND re-measured T 1 Qo. L • No significant difference in Qo. L between T 1 and T 2 BUT significant reduction in re-measure of Qo. L (than they had reported at T 1).

MODELS OF ADJUSTMENT Adjustment or adaptation means different things depending on one’s perspective i. e. : – Medical perspective: adaptation implies changed pathology, symptom reduction and physical adjustment. – Psychological perspective: adaptation implies emotional wellbeing, lack of distress, cognitive adaptation, possibly reduced psychiatric morbidity and coping. – Biopsychosocial perspective: adaptation considers all the above, plus the nature and extent of social adjustment or functioning. Walker et al. (2004) consider that the biopsychosocial approach best ‘fits’ the chronic disease experience.