MUS Somatisation Functional somatic distress disorders Frank Rhricht

- Slides: 25

MUS / Somatisation / Functional somatic (distress) disorders Frank Röhricht MD, FRCPsych Medical Director Honorary Professor of Psychiatry & Nina Papadopoulos Senior Dance Movement Psychotherapist MUS Project Manager and Clinical Supervisor

What I hope to cover 1. Overview of MUS 2. Main Characteristics 3. Patients' explanatory beliefs and expectations 4. Body oriented management: our model 5. Key findings

What is it about? • Medically unexplained symptoms (MUS) refer to persistent bodily complaints for which adequate examination (including investigation) does not reveal sufficiently explanatory structural or other specified pathology • “These symptoms are often chronic in nature (for example, persistent pain, tiredness or gastric symptoms); they can cause people significant distress, and often have an important psychological component. ” Kings Fund, March 2016

It’s costly in three ways: 1 patients… • Significant health concerns, distress, functional impairment • When compared with other chronically ill patients, MUS patients report lower quality of life, comparable or greater impairment of physical function, poorer perceived general health and worse mental health. (Smith et al. 1986)

It’s costly for GPs… • GPs see large numbers of patients with somatisation (appr. 30 -50%) of patients in PC Wessely et al. 1997, Gureje et al. 1998, Hartz et al. 2000; Nimnuan et al. 2001 • GP frustration is tied to a range of negative emotions, including feelings of inadequacy, resentment and a fear of patients who may manipulate the course of treatment Wileman et al. 2002

It’s costly… • “Such. . . disorders are often a burden for the sufferers, costly for society and difficult to treat. ” (Fink & Rosendal 2008) • The NHS in England is estimated to spend at least £ 3 billion each year…to diagnose and treat MUS, total societal costs = around £ 18 billion (Bermingham et al 2010) • “Much of this expenditure currently delivers limited value to patients; at worst, it can be counterproductive or even harmful. ” (The Kings Fund 2016)

Main characteristics • • Pattern of symptoms emerging before age of 30 Recurring nature Predominantly multiple sites or generalised pain Symptoms neither intentionally produced, not fully explained • Medical attention seeking behaviour • Impairment of social/interpersonal/occupational functioning

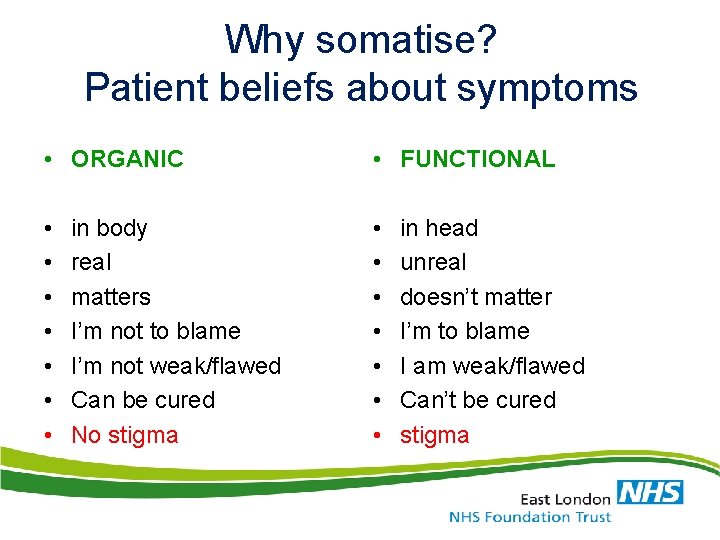

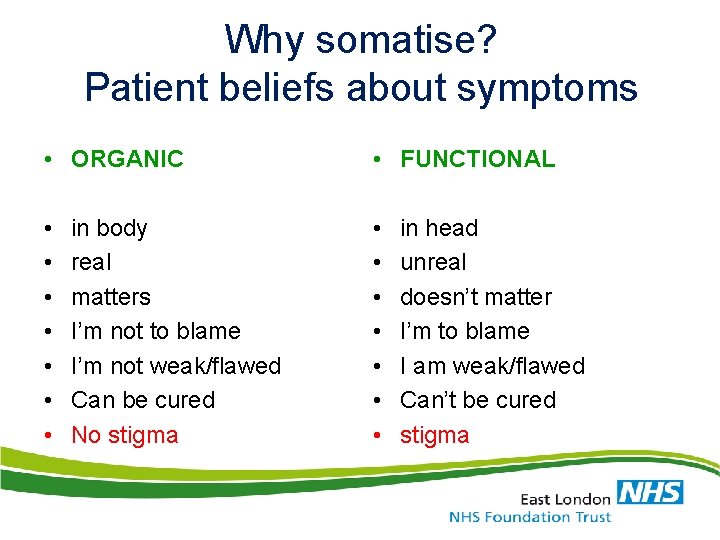

Why somatise? Patient beliefs about symptoms • ORGANIC • FUNCTIONAL • • • • in body real matters I’m not to blame I’m not weak/flawed Can be cured No stigma in head unreal doesn’t matter I’m to blame I am weak/flawed Can’t be cured stigma

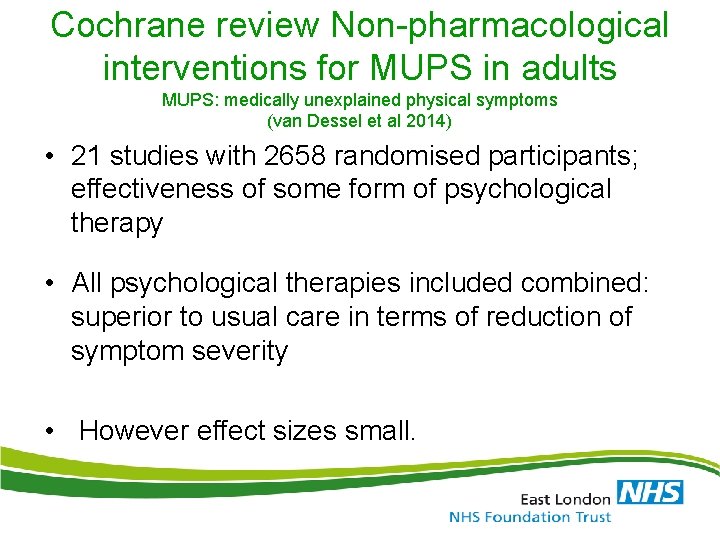

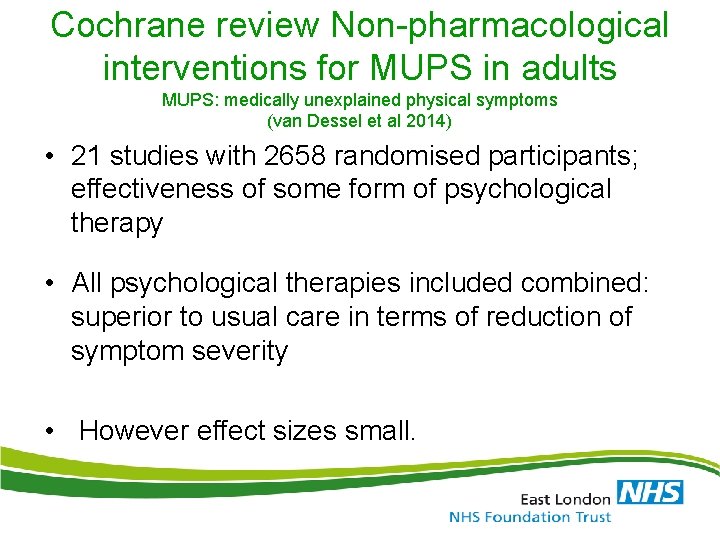

Cochrane review Non-pharmacological interventions for MUPS in adults MUPS: medically unexplained physical symptoms (van Dessel et al 2014) • 21 studies with 2658 randomised participants; effectiveness of some form of psychological therapy • All psychological therapies included combined: superior to usual care in terms of reduction of symptom severity • However effect sizes small.

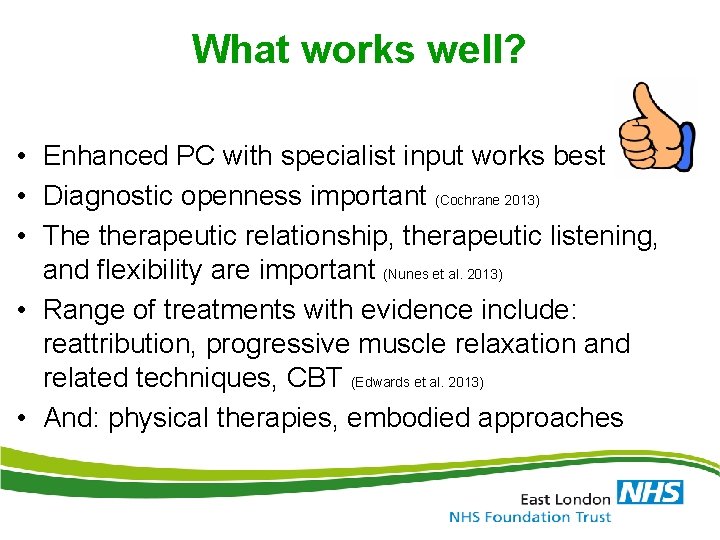

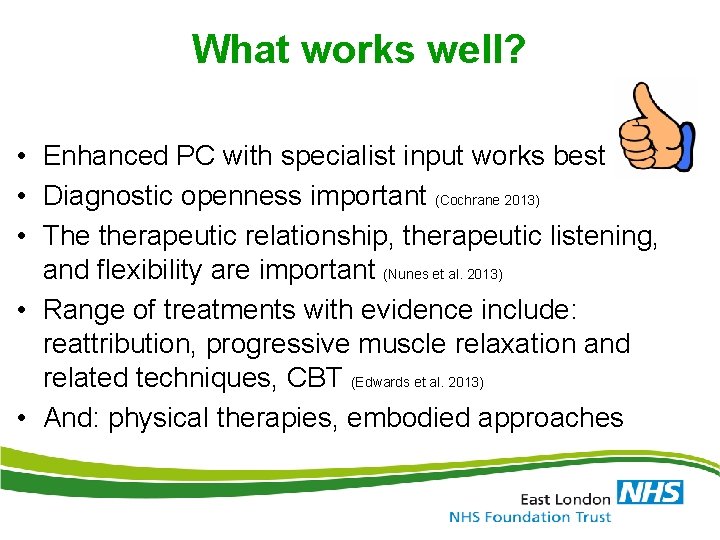

What works well? • Enhanced PC with specialist input works best • Diagnostic openness important (Cochrane 2013) • The therapeutic relationship, therapeutic listening, and flexibility are important (Nunes et al. 2013) • Range of treatments with evidence include: reattribution, progressive muscle relaxation and related techniques, CBT (Edwards et al. 2013) • And: physical therapies, embodied approaches

BEST PRACTICE IN MUS CARE: THE “DO’S & “DON’T’S”

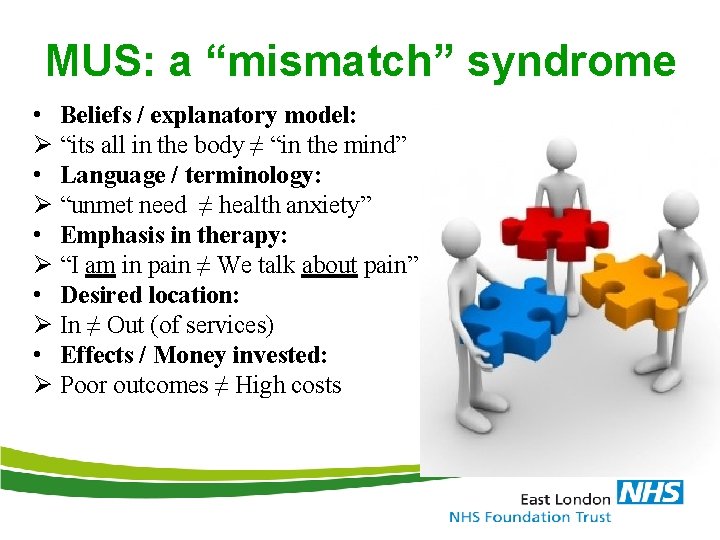

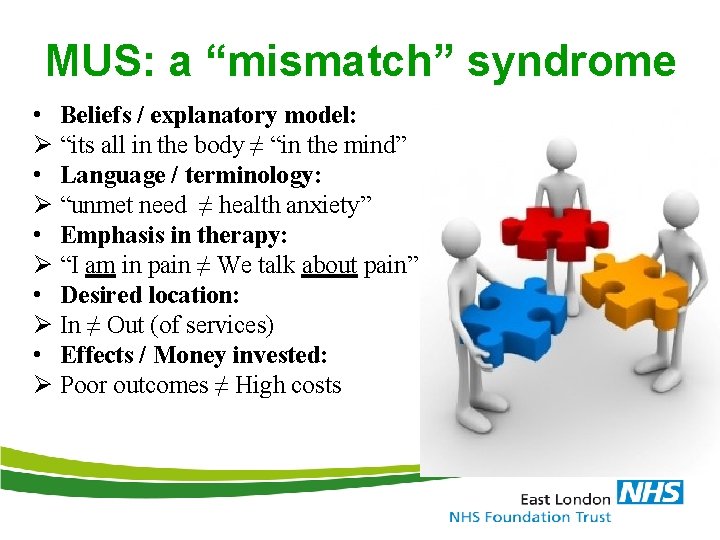

MUS: a “mismatch” syndrome • Beliefs / explanatory model: Ø “its all in the body ≠ “in the mind” • Language / terminology: Ø “unmet need ≠ health anxiety” • Emphasis in therapy: Ø “I am in pain ≠ We talk about pain” • Desired location: Ø In ≠ Out (of services) • Effects / Money invested: Ø Poor outcomes ≠ High costs

Key physician behaviours (Do’s): • Understand the patient, i. e. the effect the symptoms are having on them. • Show patient you believe they have the symptoms. • Be honest when a patient has unusual symptoms • Think about how you can empower the patient • Explain the links between physical and psychological stresses • Negotiate a culturally responsive explanation • Normalise: all symptoms are bio-psycho-social sources including Rosendal et al (2005), Salmon et al (1999), Morriss et al (2006), Guthrie (2008), and Smith et al (2003).

MUS: actually we can and should explain such symptoms (Danczak, A. Br J Gen Pract 2017)

Explanation to patient “the stress you have been under recently has led to contractions in the muscles around the gut (which is like a tube); this leads to pain and discomfort experienced in your abdomen; …. let’s talk about ways in which we can help you to manage and control the pain” Salmon P et al. Br Med J 1999; 318: 372

Key physician behaviours (Don’ts): • Tell them that you can find nothing wrong. There is something wrong. • Tell them the symptoms are normal. They are not normal for the patient. • Reassure repeatedly (never ending cycle). • Tell them there is nothing you can do to help. • Give results of normal tests and reassure and think that this will help.

Integrated MUS primary care - a person centered “one-stop-shop” service Röhricht, F. , Papadopoulos, N. , Zammit, I. (BJGPopen, 2017)

OBJECTIVES • Deliver an integrated care package incorporating best practice from primary and secondary care • Increase MUS patient satisfaction through adequate treatment, signposting and care • Improve engagement techniques between clinical professionals and MUS patients • Make the patient feel understood , enhance their coping • Reduce the intensity/frequency of somatic complaints and improve functioning • Reduce unplanned attendance in health care

How? Holistic, Body based, patient centered… • Identification: Specific somatic symptom algorithm • Engagement strategy is empathic: Ø interest in and time for the physical complaints (how, when, where, under which circumstances…) • Assessment is focused: Ø Range of in-depth somatic symptom questionnaires, health related quality of life measures • Interventions are non-verbal / embodied: Ø explicitly focusing upon / engaging with bodily symptoms (MBSR / Body Oriented Psychological Interventions as “SBLG”)

Clinical Algorithm for Screening Identifying suitable patients • pain in different locations (unspecific, unexplained) • non-specific complaints affecting multiple organ systems (unspecific, unexplained) • repeated complaints of fatigue or exhaustion • Physical symptoms occurring in the context of a stressful lifestyle or stressful life events • somatisation “plus” (anxiety/low mood/tension) • Frequent attending for PC consultations • Frequent requests for investigations

Some quotes from patients after taking part in one of the two intervention groups “I am now helping my self rather than depending completely on family” “I learned to be kind to myself…. It has really turned my life around and empowered me. . “ “It made me realise I was in denial about the wider picture of my life” “When I was there I found I was not the only one going through these problems which I think are unexplained. ”

Outcomes The Strength of the Model: Addressing 3 “costs” 1. Patients: Improvement in Qo. L and somatic symptom levels 2. Professionals: Gave ‘hope’ 3. Society: reduced service utilization

Discussion / Key findings • • • Managing MUS in PC: it is not, never was/will be easy PC embedded models work best It is possible to engage patients from all backgrounds High level of sensitivity required: cultural, social, personal Embodied approach accepted by 2/3 of patients with significant benefits re reduction of symptom levels & service cost • Once engaged in this primary care pathway even low level inputs make a difference

Thank you for your attention! Frank. Rohricht@nhs. net Nina. Papadopoulos@nhs. net www. mus. elft. nhs. uk

Chapter 29 somatic symptom and dissociative disorders

Chapter 29 somatic symptom and dissociative disorders Cengage

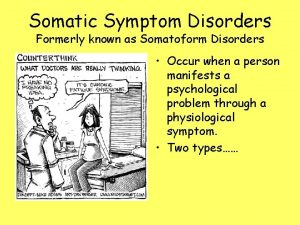

Cengage Chapter 17 somatic symptom disorders

Chapter 17 somatic symptom disorders Frank william abagnale

Frank william abagnale Mus musculus life cycle

Mus musculus life cycle Vatvalandė

Vatvalandė Kaip inercija padeda zaisti krepsini

Kaip inercija padeda zaisti krepsini Baltos sviesos skaidymas i spektra

Baltos sviesos skaidymas i spektra Monetary unit sampling

Monetary unit sampling Ni mus

Ni mus [email protected]

[email protected] M s t mus tis nt

M s t mus tis nt Arbejdstidsplanlægning

Arbejdstidsplanlægning Mutacin

Mutacin Mus (rod)

Mus (rod) Mus-samtale forberedelsesskema

Mus-samtale forberedelsesskema Søren banjomus sangtekst

Søren banjomus sangtekst Transpalatal arch space maintainer

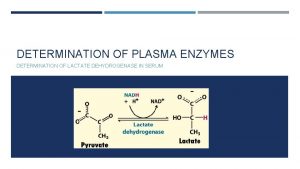

Transpalatal arch space maintainer Non functional plasma enzymes

Non functional plasma enzymes Enzymes of blood plasma

Enzymes of blood plasma Functional and non functional

Functional and non functional Respiratory distress

Respiratory distress Respiratory distress nasal flaring

Respiratory distress nasal flaring Grading of meconium stained liquor ppt

Grading of meconium stained liquor ppt Emotional thermometer

Emotional thermometer Modified sims position for prolapsed cord

Modified sims position for prolapsed cord