Argosy University Seattle WALDORF EDUCATION The secret of

- Slides: 19

Argosy University, Seattle WALDORF EDUCATION The secret of American schooling is not that it doesn’t teach the way children learn. It’s that it isn’t supposed to teach about being a strong, self-directed man or woman. . . Jackie A. Giuliano, Ph. D. © 2006 Jackie Alan Giuliano All Rights Reserved

Love the questions. . . Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart And try to love the questions themselves. Do not now seek the answers that cannot be given you Because you would not be able to live them. And the point is to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will gradually, Without noticing it, Live along some distant day Into the answer. n -- Rainer Maria Rilke

Many educational approaches n Many educational models are embracing new (old? ) principles of learning. n Waldorf Education is a good example n Check out http: //www. raphaelhouse. school. nz/index. php? pid=2 n The following presentation is adapted from this website

Waldorf Education – Rudolf Steiner n Teachers in these schools are dedicated to generating a genuine inner enthusiasm for learning within every child. n They achieve this in a variety of ways. Even a seemingly dry and academic subject will receive a pictorial or dynamic presentation. n This method removes the pressure for competitive testing, placing and reward; motivation can arise from within. n Ways in which the Waldorf approach to education differs from others n the response of the curriculum to the various phases in child development; n the crucial though changing relationship between teacher and child as these various phases are met. n

The essential phases in childhood. . . n Rudolf Steiner drew particular attention to three essential phases, and the corresponding needs and capabilities of the child within each of them. n The first seven years - imitation n Apparently helpless in his mother's arms, the infant may seem to be incapable of learning. n n n In fact he is at his most absorptive stage. From birth he is learning to stand, to talk and to think. Uprightness, the acquisition of language and the ability to think are gigantic achievements in a period of three or four years. And they are learned without benefit of instruction! The child gains them through a combination of latent ability, instinct and above all imitation. The last one is the specific talent that characterizes the period up to the age of 6 or 7; § the young child mimics everything in the environment uncritically - not only the sounds of speech, the gestures of people (and machines!) but the attitudes and values of parents and peers.

The heart of childhood - imagination n A transition occurs at around 7, the most prominent physical change being the loss of the milk teeth. n On the one hand the child develops a new and vivid life of imagination; n on the other, a readiness for more formal learning. n He both expresses and experiences life through finely shaded feelings. n As he moves through these years the faculty for more consecutive thought also begins to unfold. n Yet careful handling is necessary, for while this faculty needs nurturing, the ability to be fully at home in the pictorial world of imagination remains the child's most vital asset.

Towards adulthood - rational judgment n It is the third development stage - adolescence - that is crucial for the right cultivation of critical judgment. n At this point, it becomes possible for the pupil to use thinking as an objective instrument. n Two other features are present in the adolescent psyche: n n n first, a healthy, valuable idealism; second, a vulnerable sensitivity about one's own feelings and inner experiences. These traits need protection, and many youngsters from puberty onwards are energetic in disguising their inner condition: n n n girls may become coquettish, daring and defiant; boys' defenses may well take the form of sullen or introverted behavior, apparent unwillingness to communicate or a hard shell. In any case, a barrier is erected as self-protection. The person behind the barrier is constantly seeking a model, with qualities to emulate.

The pre-school child n Learning is the key to human development, but it is not a simple, homogeneous process. n What to learn, when to learn and how to learn are arrived at through a conscious and careful study of children as well as a comprehensive understanding of the human being through all stages of development. n The teacher strives to help the child eventually to become a clear-thinking, sensitive and well-centered adult. n To achieve this, Waldorf teachers relate to their pupils by responding to the most appropriate elements in each childhood phase.

Kindergarten - a homelike environment n The Kindergarten teacher works with the young child first by creating an environment as of a warm and loving home, rhythmically repetitive and secure. Here they respond to the developing child through two broad themes. n Firstly, teachers engage themselves in domestic, practical and artistic activities which the child can readily imitate n n Secondly, the teachers nurture the children's power of fantasy peculiar to the age in the telling of carefully selected stories n n n for example, baking, painting, gardening and handicrafts, coloring the work with the yearly flow of seasonal moods and seasonal festivals. help them to experience many aspects of life more deeply by encouraging free play. Where toys are used, they will be made of natural materials, together with cones, shells and other objects from nature that the children themselves have collected. In this truly natural, loving and creative environment, the children are given the scope and form which prepare them for the next phase of school life.

The Lower School n It is now appropriate to use the powers of understanding for more abstract matters, including writing, reading and arithmetic. n But, to the child, it is not simply the acquisition of knowledge that is important n it is the experience of what knowledge is in life, in the hearts and minds of adults whom the child needs and wishes to recognize as authorities. n The Rudolf Steiner school responds to this need by introducing the Class Teacher n the key authority, though by no means the only teacher of the class, between the 'change of teeth' and puberty. n The Class Teacher's appointment ideally is for seven years. It is the Class Teacher's task to guide this group of children during these important and impressionable years, and to teach the class many of the curriculum subjects.

The lower school. . . n During these years - Classes 1 to 7 - all the basic skills of literacy and numeracy are imparted, and all cultural activities which cultivate the imaginative faculties n recitation of poetry, drawing, painting, drama, music n In both the practical and cultural activities, however, the essence of the teacher's task is to work with his pupils as 'artist'. n It is not that the child should simply be taught 'art', but that he should be taught so-called 'non-art' subjects imaginatively and artistically. n This is true, though in widely different ways, of mathematics and grammar, carpentry and knitting, sports and foreign languages, all of which appear in the Waldorf curriculum.

Examples n For example, it is more important in 'history' that the children share the anguish of Martin Luther over the decadence of the Church than that they should learn the significant dates of Luther's biography. n But the latter becomes more meaningful if they have experienced the former. n In geography, the picture of the climatic zones of Africa will be clearer to the child if the teacher can convey, artistically, descriptively, dramatically, n the atmosphere of the burning dry Sahara, n of the fetid clammy rain forest of the Guinea Coast, n or the wet-and-dry seasonal swings of the great grasslands of the Eastern plateau.

Developing reverence. . . n In the natural sciences, the sense of awe and wonder is cultivated at this age. n Such a mood can arise, for example, when studying the human body, and discovering the vital relationship between the hardest of substances, bone, and the quickest of cells (produced in the bones), the red corpuscles. n in examining the modes of seed production in lower and higher plants, that there is an evolutionary sequence, a connected progression. n This sense of awe and wonder will develop also into a feeling of reverence that may be a firm foundation for a healthier treatment of the environment in later life. n And it should underlie - yet never undermine - the critical faculties that the study of science both requires and develops in the later stages of education.

Primarily about feelings. . . n The teacher is appealing primarily to the feelings of the child between seven and fourteen n the child's relationship is more likely to be shaped by the teacher's power and efforts as 'artist' than by the inherent subject matter. n To support such an approach, everything in a Waldorf school, from the classroom furnishings to the way a poem is recited, n from the kind of pen a pupil uses n to the exercises in the gymnasium, n is considered with two criteria in mind: n they should be functional or utilitarian, and n beautiful. n For the children this guarantees a caring authority that works on their own sensibilities. n

The Main Lesson n In the Lower School, the Class Teacher does his or her work principally in the Main Lesson. n This period of two hours or so beginning the day in all Waldorf schools, can be a rich experience. n The teacher organizes the subject matter to create a balanced appeal to the pupils' intellect, feelings and will. n The thinking element will arise through listening, understanding, remembering or discussing; n the feeling element will be cultivated through artistic work or experience; n the will element will be engaged through an activity: n n a set task of writing, map drawing or constructing models, for example, or through movement itself in some form. However, at this age, the Class Teacher does not yet appeal to the child's latent powers of discrimination or critical judgment.

The Upper School n The 7 - 12 year old expects adults to know everything, and the young teenager still hopes for it. n If these hopes and expectations of authority are satisfied during the first eight years in a Waldorf school, pupils will be able to exercise authority over themselves in adulthood all the more effectively. n In the Upper School, Classes 8/9 to 12, a new image of the adult stands in the youngster's mind as an ideal. n Thoughtful, self-possessed, considerate, strong-minded, warm-hearted. n From around age fourteen, the students look for such qualities in their teachers. n They no longer accept their authority, but want to follow a personal leader of their own choosing.

Last but not least. . . n The Upper School Student can realize this vision of adulthood in teachers who are clearly experts through n having devoted themselves to the mastery of their subject, n to the logic in mathematics, n to the control of hand sharpening of eye in metal-work and wood-carving, or n to the development of bodily grace, control and expression in eurhythmy and gymnastics.

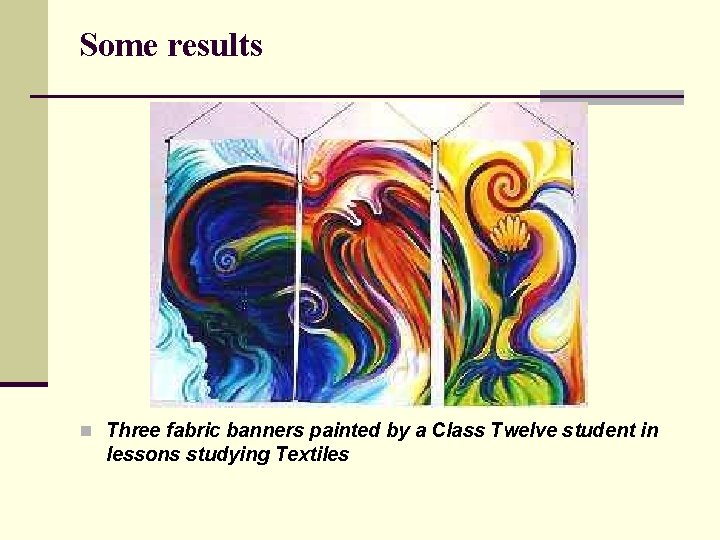

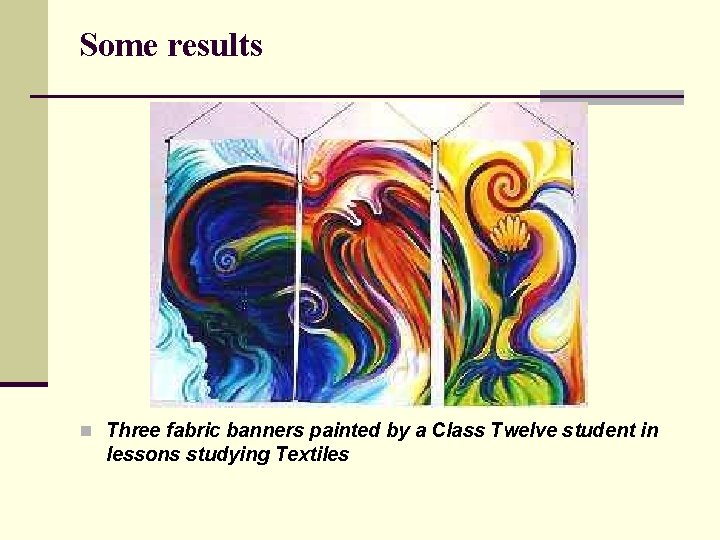

Some results n Three fabric banners painted by a Class Twelve student in lessons studying Textiles

In Summary n The Waldorf curriculum is comprehensive, covering a wide range of subject-matter, all of which is encountered by all pupils in a Waldorf school over a twelve-year period between the ages of six and eighteen. n Waldorf teachers feel that the early specialization often demanded in education of children, particularly teenagers, is a denial of the importance of the holistic treatment of the whole human being. n At the same time, pupils' individual talents, in whatever field, are fully recognized, guided and encouraged.

Pros and cons of waldorf

Pros and cons of waldorf Pedagogia waldorf caracteristici

Pedagogia waldorf caracteristici Waldorf color theory

Waldorf color theory Waldorf graduates statistics

Waldorf graduates statistics Seattle university albers school of business

Seattle university albers school of business Seattle university school of theology and ministry

Seattle university school of theology and ministry Seattle university endowment

Seattle university endowment Southeast seattle education coalition

Southeast seattle education coalition Hình ảnh bộ gõ cơ thể búng tay

Hình ảnh bộ gõ cơ thể búng tay Lp html

Lp html Bổ thể

Bổ thể Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em

Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em Voi kéo gỗ như thế nào

Voi kéo gỗ như thế nào Chụp tư thế worms-breton

Chụp tư thế worms-breton Bài hát chúa yêu trần thế alleluia

Bài hát chúa yêu trần thế alleluia Môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng chữ đua

Môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng chữ đua Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất

Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Công của trọng lực

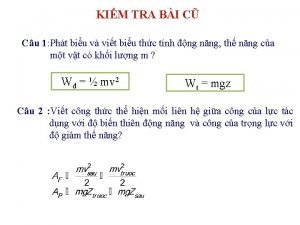

Công của trọng lực Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ

Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ