Understanding difficult patients understanding ourselves STFM Annual Spring

- Slides: 48

Understanding difficult patients; understanding ourselves STFM Annual Spring Conference May 4, 2013 Jennifer Edgoose, MD, MPH Caitlin Regner, BS University of Wisconsin-Madison Contact info: Jennifer. edgoose@fammed. wisc. edu

Objectives • Introduce results of two studies regarding “difficult” patients • The first explores the patient perspective • The second assesses a tool to assist clinicians with their visits with difficult patients. • Can we move toward greater understanding of our patients and ourselves?

Background • Difficult patients • Heartsink patients who “…evoke an overwhelming mixture of exasperation, defeat and sometimes plain dislike…” Dr. Tom O’Dowd, BMJ, 1988 Photo by cellar_door_films • 1 in 6 ambulatory encounters

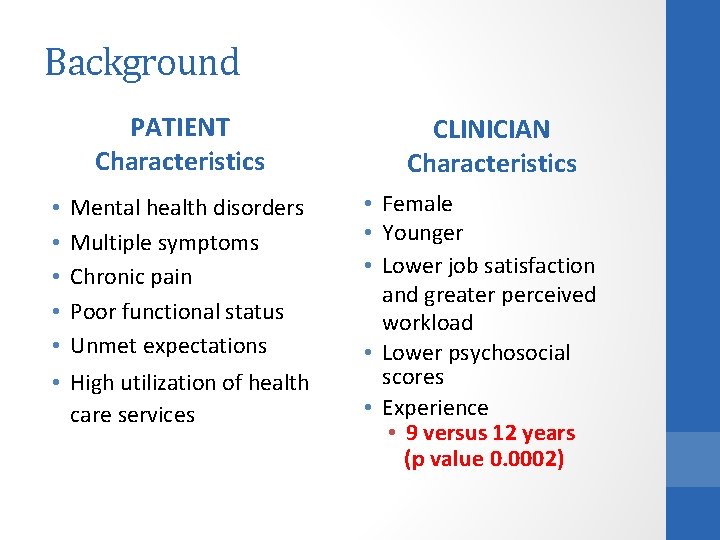

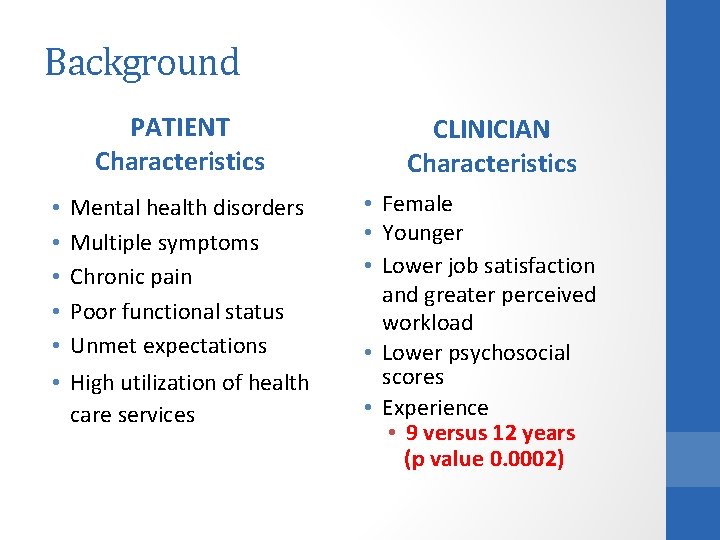

Background PATIENT Characteristics • • • Mental health disorders Multiple symptoms Chronic pain Poor functional status Unmet expectations • High utilization of health care services CLINICIAN Characteristics • Female • Younger • Lower job satisfaction and greater perceived workload • Lower psychosocial scores • Experience • 9 versus 12 years (p value 0. 0002)

Research Question #1 • If physicians find their relationships with difficult patients to be frustrating, if not overwhelming, … …do difficult patients also find these relationships to be equally challenging?

Study design • Cross-sectional study • Patient inclusion criteria: • Patients of 12 family medicine residents • 18 years or older • Patients were assigned coded numbers and notified of study at clinic check-in. • Residents indicated difficult patients for that day • Only coded numbers were submitted to maintain patient confidentiality

Study design Survey completed through • • • Option 1: interview by medical student Option 2: written self completion Basic Demographic Data collected: • • • Gender English speaking or non-English speaking Ethnicity/Race Education Level 5 Questions developed • • • Graded on a Likert Scale from 1 -7 Comments optional for each question

Patient questionnaire 1. In general, how easy is it for you to talk with your doctor? 2. How easy do you think your medical problems are for your doctor to deal with? 3. How much control do you feel you have over your health care decisions? 4. How often do you feel your doctor addresses your concerns during your appointments? 5. How often does your doctor ask you non-medical questions to help understand your concerns during your appointments? (e. g. What is your occupation or job? ; Where are you from? ; Who do you live with? ; Do you have access to a car? ; Do you have problems paying for your medicines? )

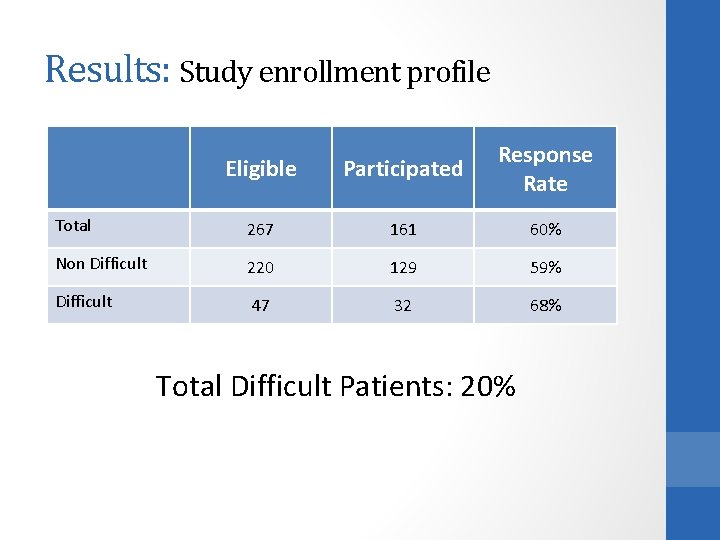

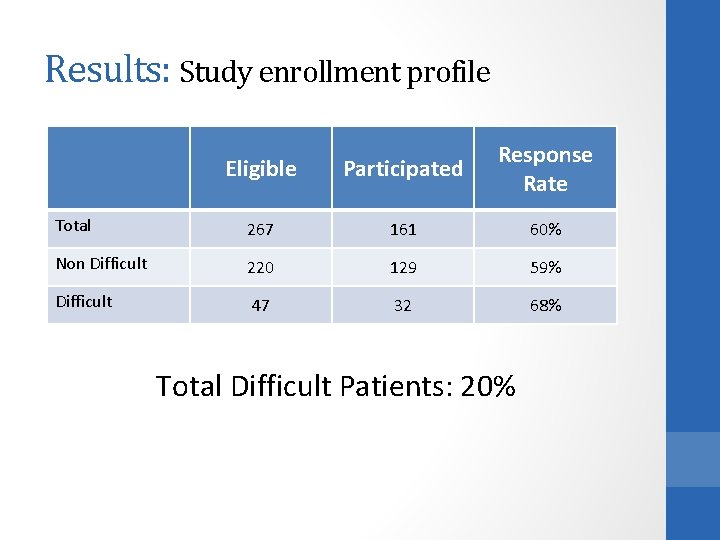

Results: Study enrollment profile Eligible Participated Response Rate Total 267 161 60% Non Difficult 220 129 59% Difficult 47 32 68% Total Difficult Patients: 20%

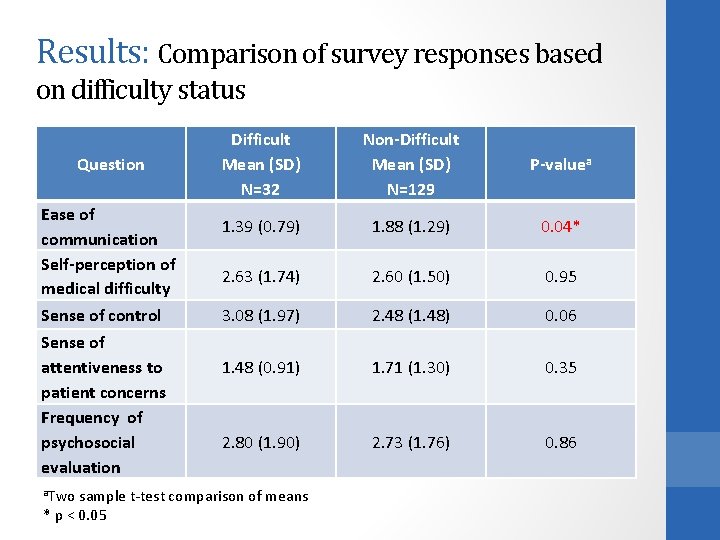

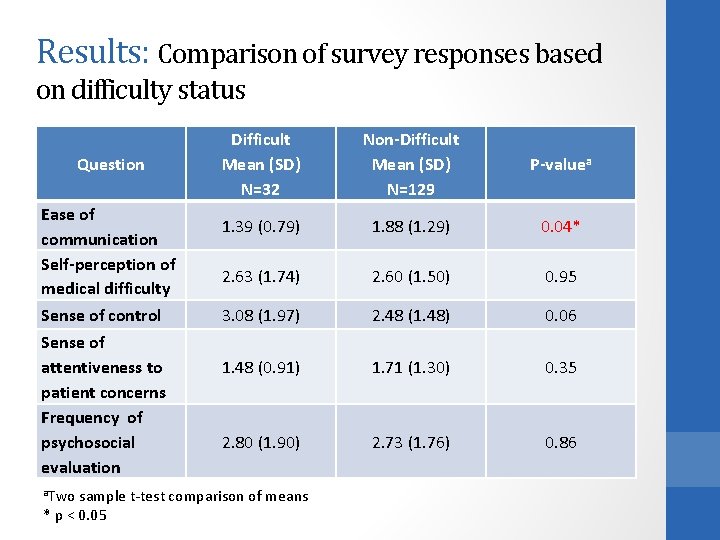

Results: Comparison of survey responses based on difficulty status Question Ease of communication Self-perception of medical difficulty Sense of control Sense of attentiveness to patient concerns Frequency of psychosocial evaluation a. Two Difficult Mean (SD) N=32 Non-Difficult Mean (SD) N=129 P-valuea 1. 39 (0. 79) 1. 88 (1. 29) 0. 04* 2. 63 (1. 74) 2. 60 (1. 50) 0. 95 3. 08 (1. 97) 2. 48 (1. 48) 0. 06 1. 48 (0. 91) 1. 71 (1. 30) 0. 35 2. 80 (1. 90) 2. 73 (1. 76) 0. 86 sample t-test comparison of means * p < 0. 05

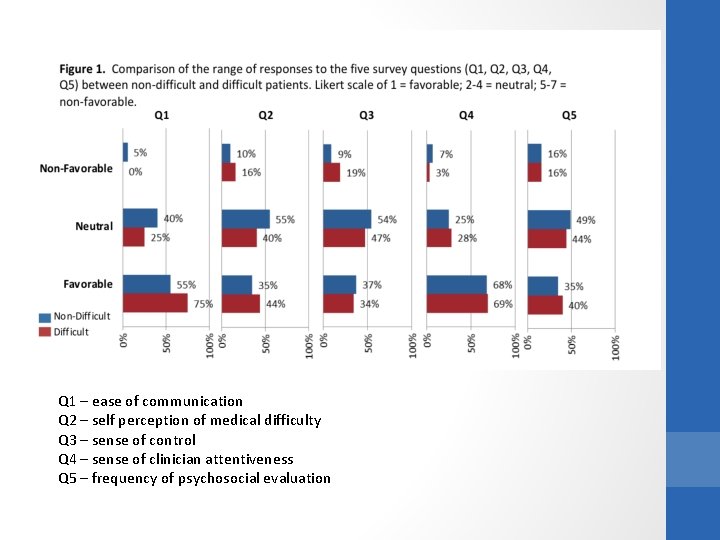

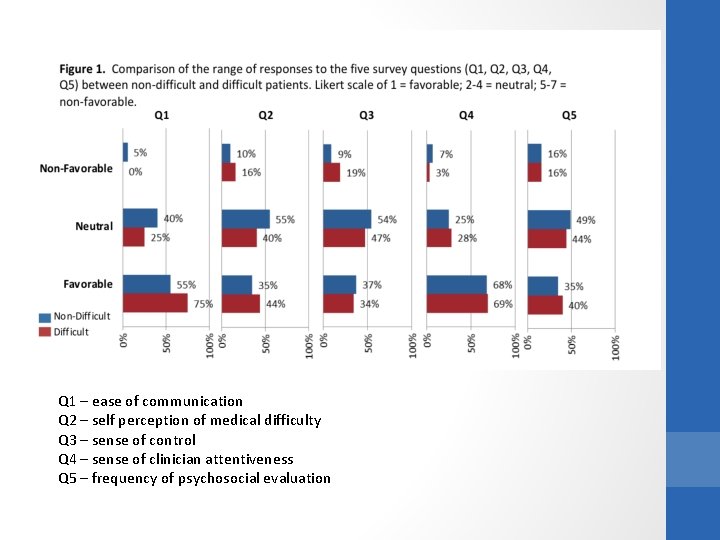

Q 1 – ease of communication Q 2 – self perception of medical difficulty Q 3 – sense of control Q 4 – sense of clinician attentiveness Q 5 – frequency of psychosocial evaluation

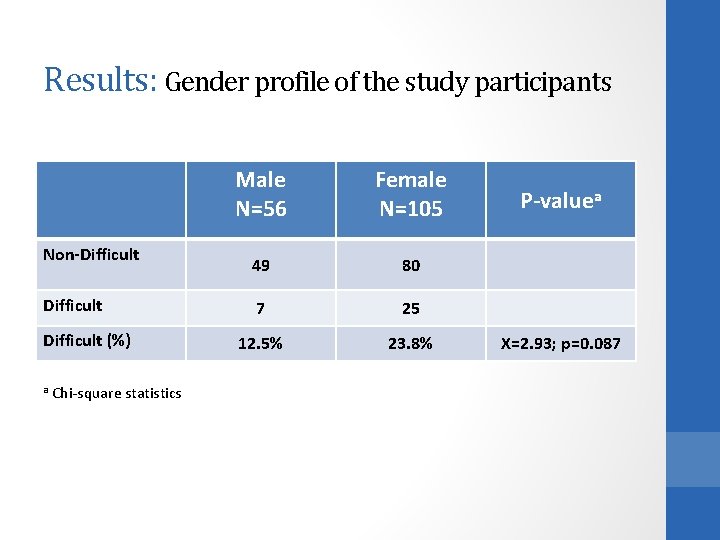

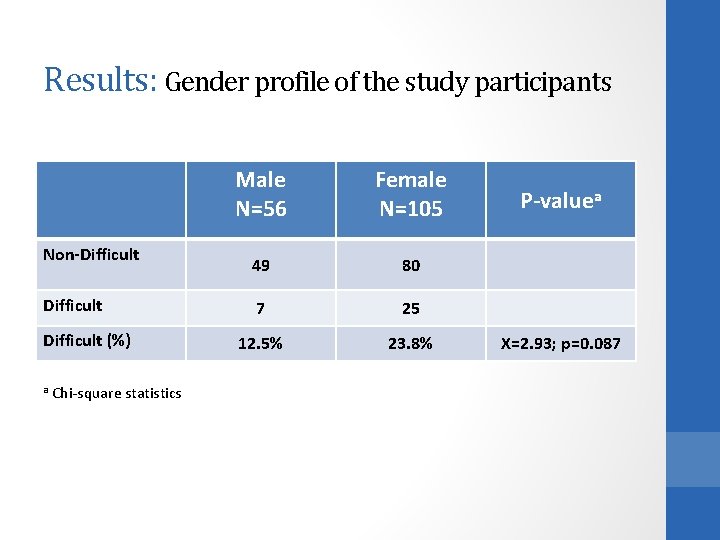

Results: Gender profile of the study participants Non-Difficult (%) a Chi-square statistics Male N=56 Female N=105 49 80 7 25 12. 5% 23. 8% P-valuea X=2. 93; p=0. 087

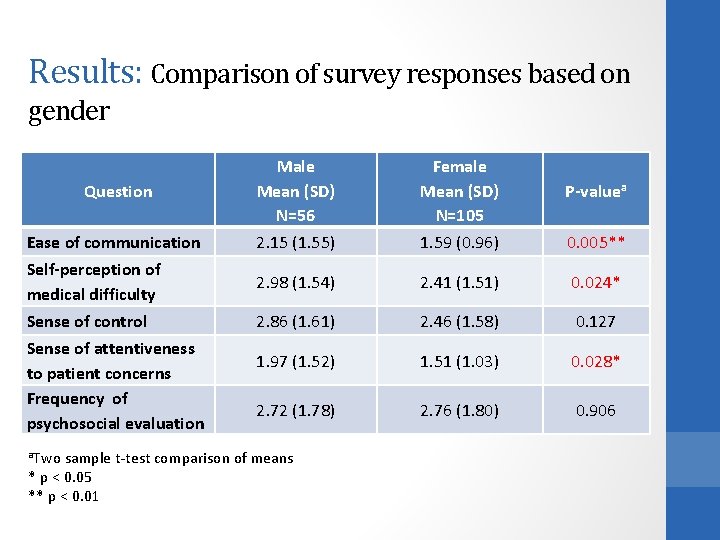

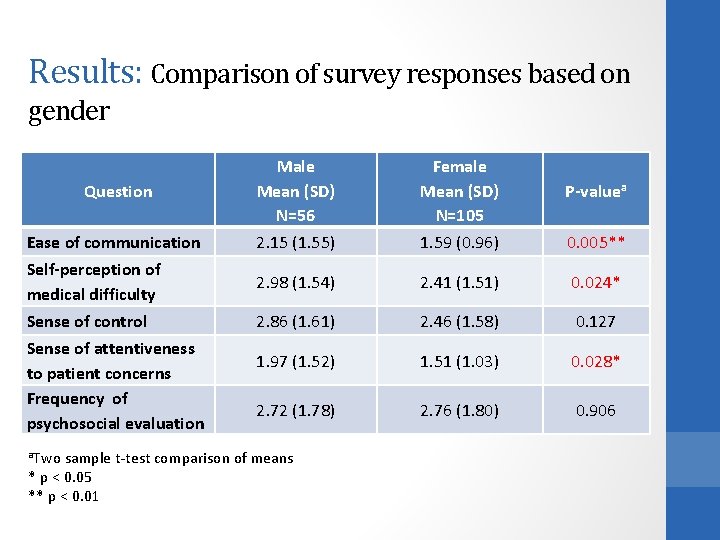

Results: Comparison of survey responses based on gender Question Male Mean (SD) N=56 Female Mean (SD) N=105 P-valuea Ease of communication 2. 15 (1. 55) 1. 59 (0. 96) 0. 005** Self-perception of medical difficulty 2. 98 (1. 54) 2. 41 (1. 51) 0. 024* Sense of control 2. 86 (1. 61) 2. 46 (1. 58) 0. 127 1. 97 (1. 52) 1. 51 (1. 03) 0. 028* 2. 72 (1. 78) 2. 76 (1. 80) 0. 906 Sense of attentiveness to patient concerns Frequency of psychosocial evaluation a. Two sample t-test comparison of means * p < 0. 05 ** p < 0. 01

Results: Multivariate Analysis of Gender, Race, Education and Difficulty • Gender is a significant predictor for questions 1, 2 and 3 (p = 0. 008; 0. 015 and 0. 046 respectively). • Thus, males report a harder time talking with their doctor; think they are more difficult for their doctor; and feel less in control of their health care decisions. Difficulty is NOT a predictor for these questions surrounding patient-doctor communication.

What does this mean ? • We speculate that provider frustration lies in the incongruity of patient and physician perspectives about their relationship. • Is the worldview of patient and provider discordant due to educational differences, language and/or personality disorders? • Schafer and Nowlis found that when analyzing 21 difficult patients, 33% of difficult patients had at least one personality disorder, particularly dependent personality disorders. • Do providers feel guilt about their feelings toward their patients and (over) compensate with extra time and energy?

Photo by Chat-Lunatique US THEM

Photo by nodeswitch . . . So who needs help in this relationship?

Research Question #2 • Can we develop a simple teaching tool that prompts clinical learners to consider and contemplate issues critical to achieving a patient -centered and self-reflective encounter with a patient whom the clinician considers “difficult”?

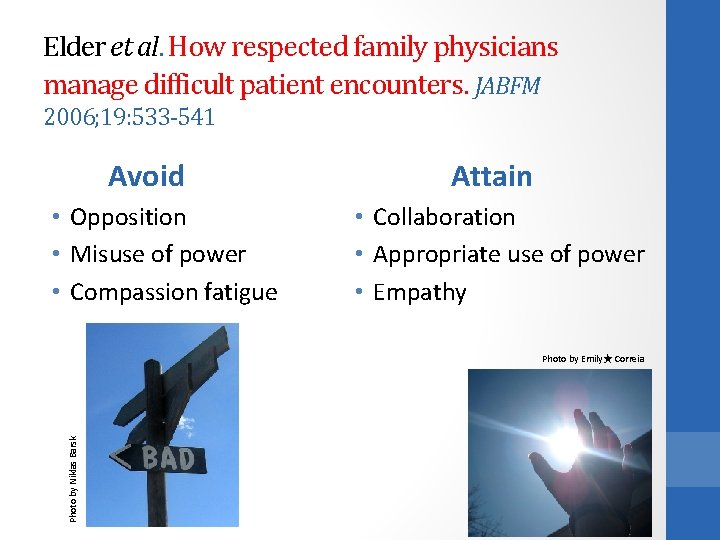

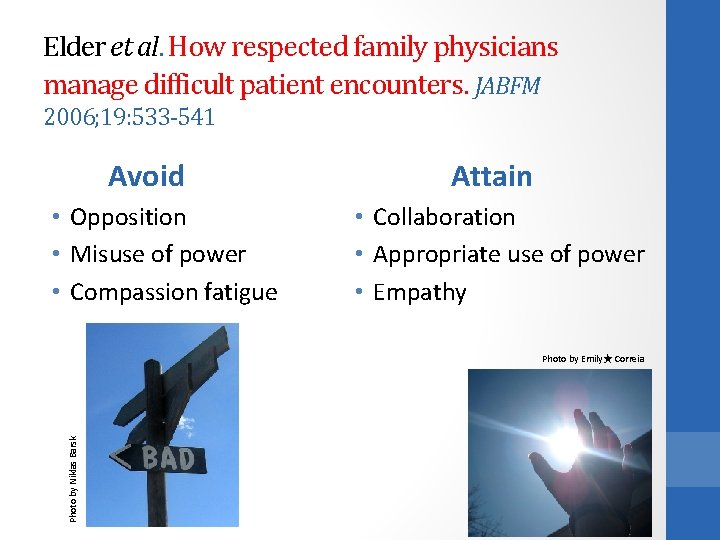

Elder et al. How respected family physicians manage difficult patient encounters. JABFM 2006; 19: 533 -541 Avoid • Opposition • Misuse of power • Compassion fatigue Attain • Collaboration • Appropriate use of power • Empathy Photo by Niklas Barsk Photo by Emily★ Correia

How to get there? • Physicians with poorer scores on the Physician Belief Scale have more difficult patient encounters • The PBS measures a clinician’s psychosocial orientation and correlates with a more patient-centered communication style Could we better explore who “they” are? Photo by timtom. ch • At the University of Wisconsin-Madison family medicine residency, social documentation was completed only 27% of the time.

How to get there? “We don’t see things as they are, we see things as we are. ” Anaïs Nin Photo by Tor HÃ¥kon Could we better explore who we are?

What do successful docs do? • “Physicians mentioned ‘psyching up’ by checking their own attitudes and recognizing their own biases, as well as trying to separate their own emotions from those of the patient, remaining open to surprises, and even using breathing exercises. ” (Elder, 2006)

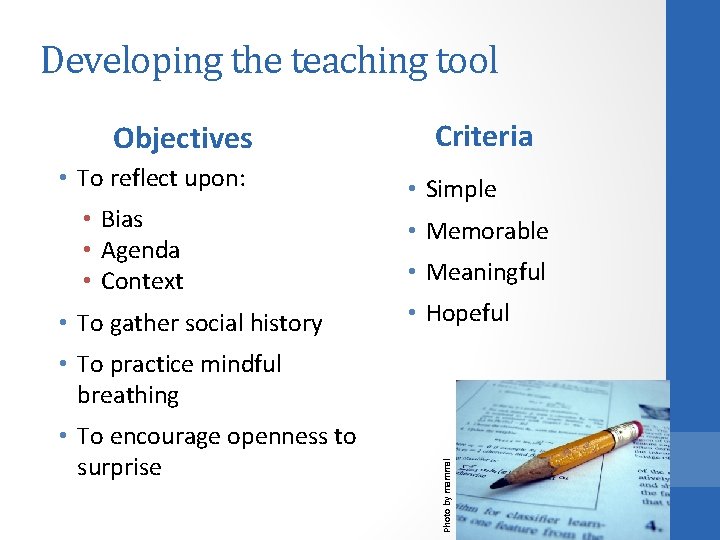

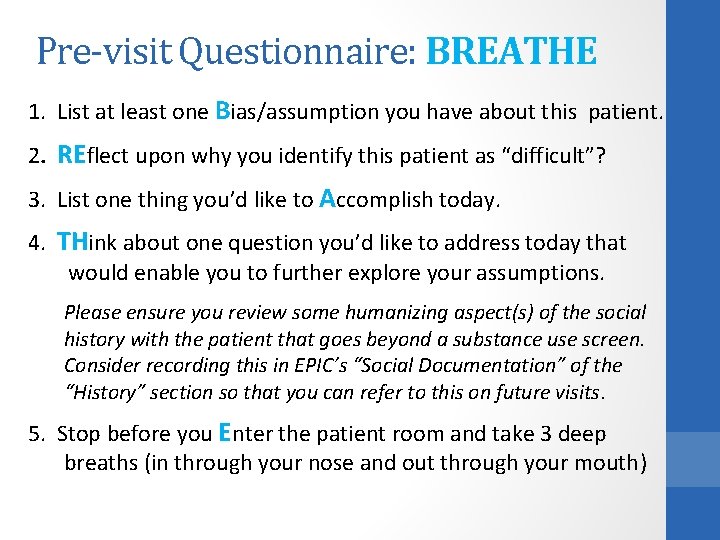

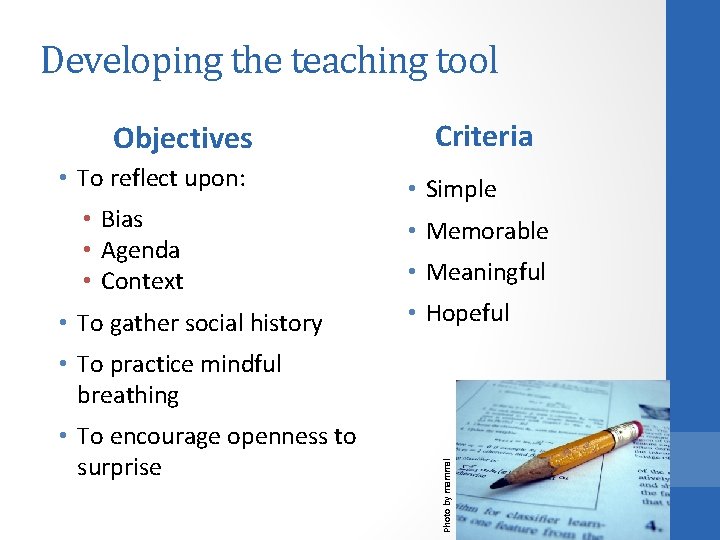

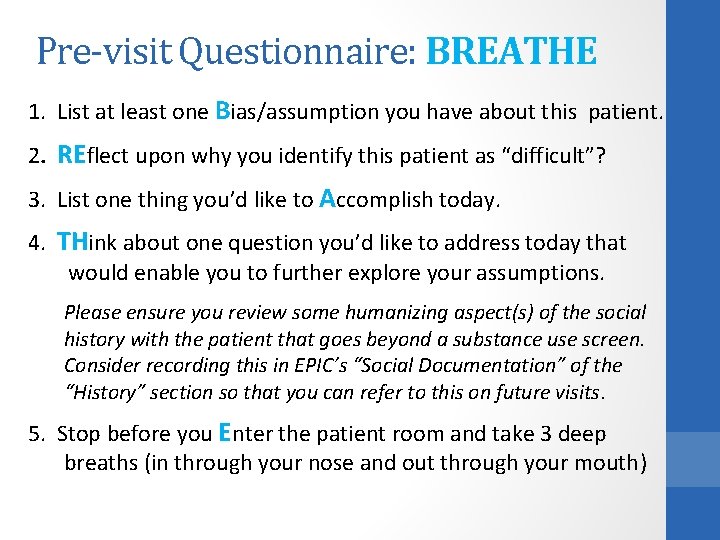

Developing the teaching tool Objectives • To reflect upon: • Bias • Agenda • Context • To gather social history Criteria • Simple • Memorable • Meaningful • Hopeful • To encourage openness to surprise Photo by mammal • To practice mindful breathing

BREATHE OUT Photo by mikak

Pre-visit Questionnaire: BREATHE 1. List at least one Bias/assumption you have about this patient. 2. REflect upon why you identify this patient as “difficult”? 3. List one thing you’d like to Accomplish today. 4. THink about one question you’d like to address today that would enable you to further explore your assumptions. Please ensure you review some humanizing aspect(s) of the social history with the patient that goes beyond a substance use screen. Consider recording this in EPIC’s “Social Documentation” of the “History” section so that you can refer to this on future visits. 5. Stop before you Enter the patient room and take 3 deep breaths (in through your nose and out through your mouth)

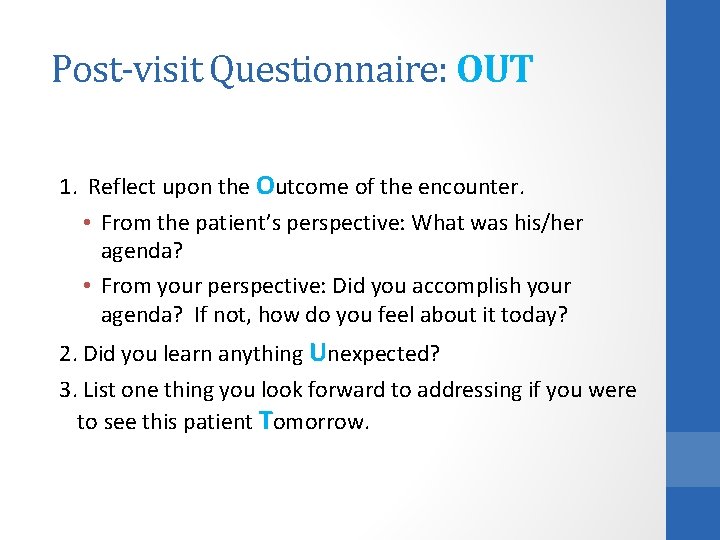

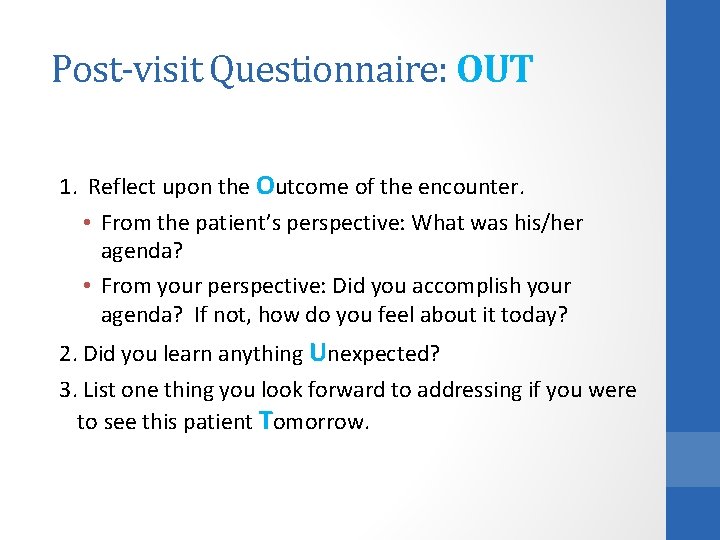

Post-visit Questionnaire: OUT 1. Reflect upon the Outcome of the encounter. • From the patient’s perspective: What was his/her agenda? • From your perspective: Did you accomplish your agenda? If not, how do you feel about it today? 2. Did you learn anything Unexpected? 3. List one thing you look forward to addressing if you were to see this patient Tomorrow.

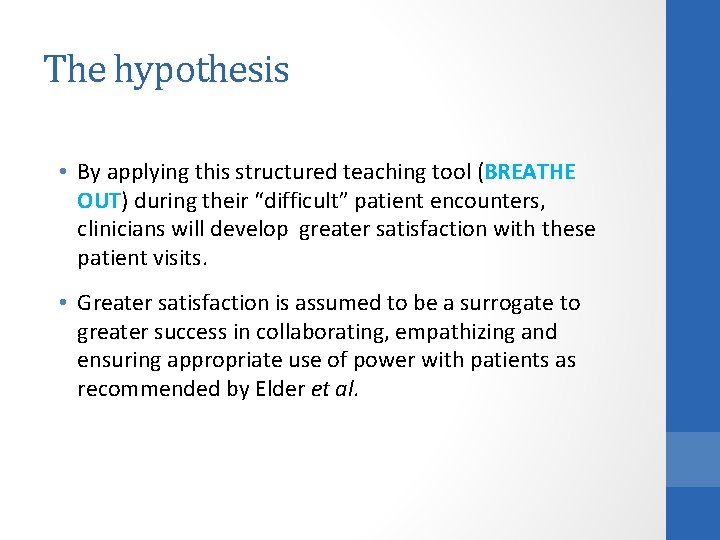

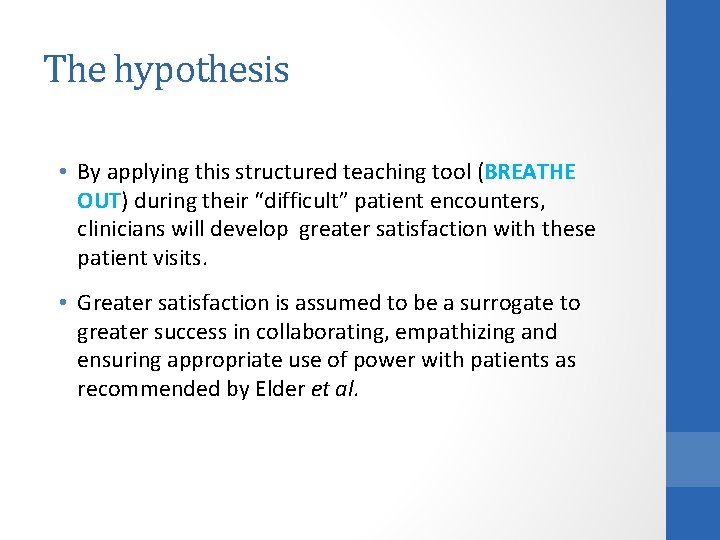

The hypothesis • By applying this structured teaching tool (BREATHE OUT) during their “difficult” patient encounters, clinicians will develop greater satisfaction with these patient visits. • Greater satisfaction is assumed to be a surrogate to greater success in collaborating, empathizing and ensuring appropriate use of power with patients as recommended by Elder et al.

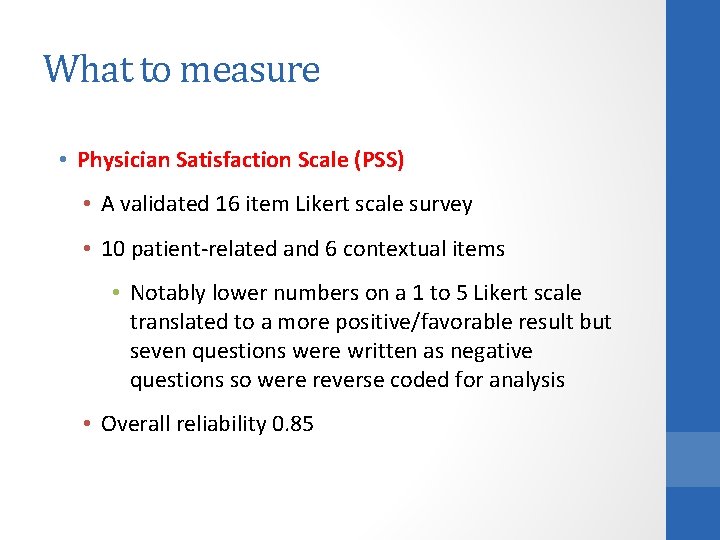

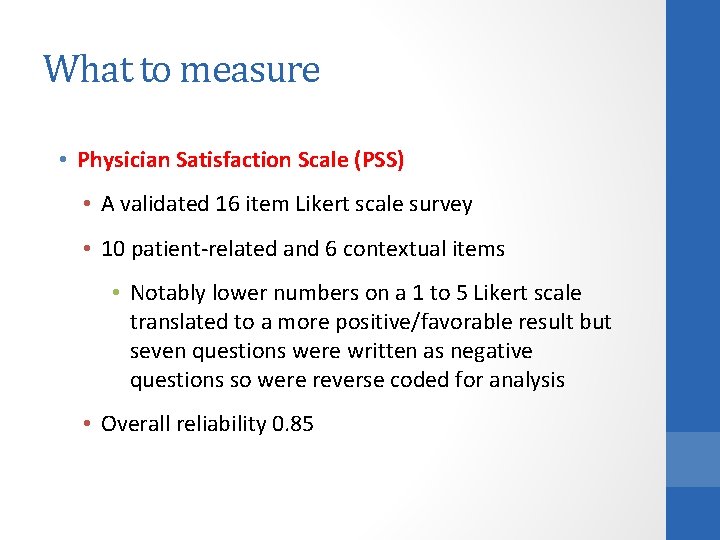

What to measure • Physician Satisfaction Scale (PSS) • A validated 16 item Likert scale survey • 10 patient-related and 6 contextual items • Notably lower numbers on a 1 to 5 Likert scale translated to a more positive/favorable result but seven questions were written as negative questions so were reverse coded for analysis • Overall reliability 0. 85

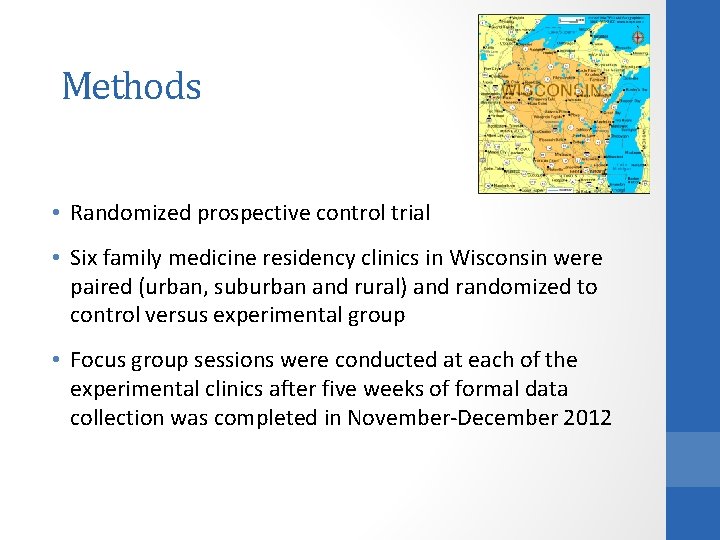

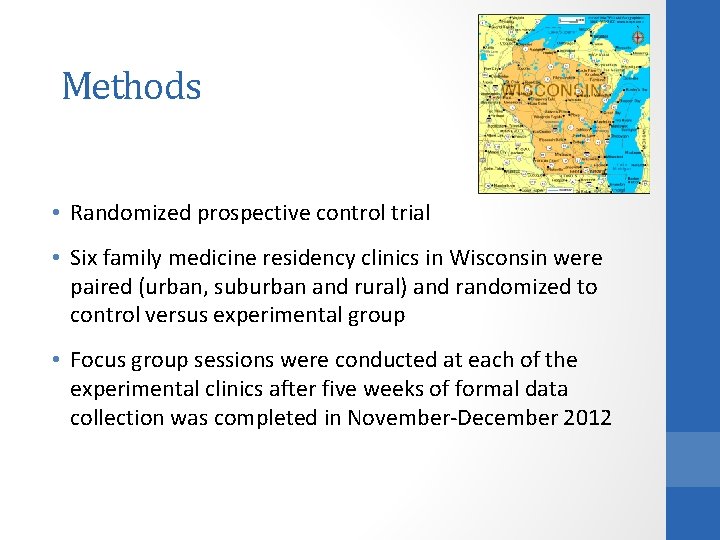

Methods • Randomized prospective control trial • Six family medicine residency clinics in Wisconsin were paired (urban, suburban and rural) and randomized to control versus experimental group • Focus group sessions were conducted at each of the experimental clinics after five weeks of formal data collection was completed in November-December 2012

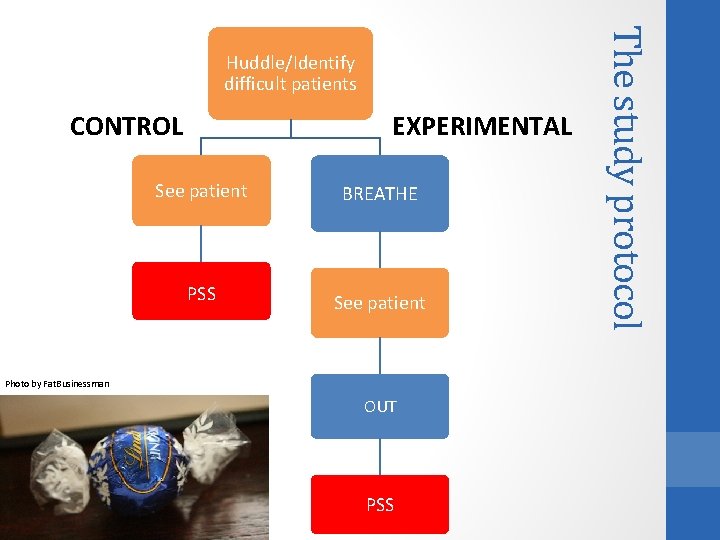

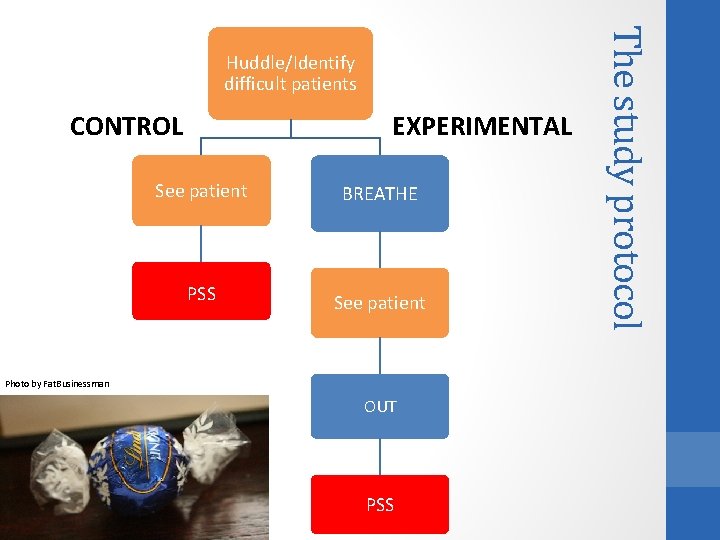

EXPERIMENTAL CONTROL See patient BREATHE PSS See patient Photo by Fat. Businessman OUT PSS The study protocol Huddle/Identify difficult patients

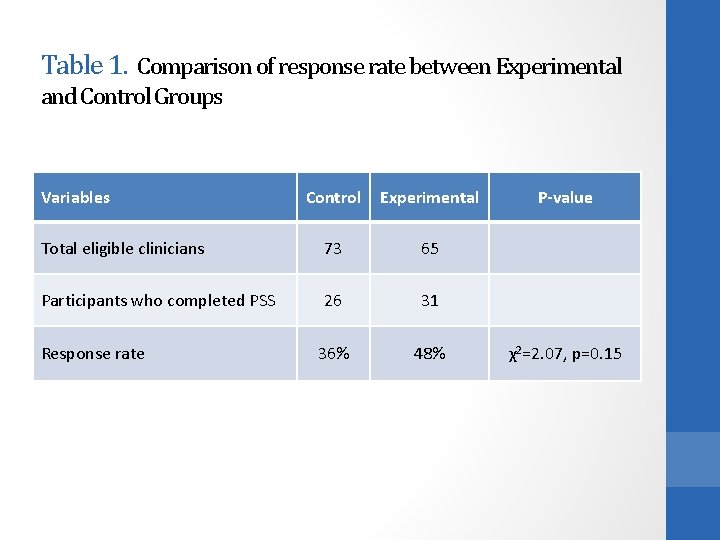

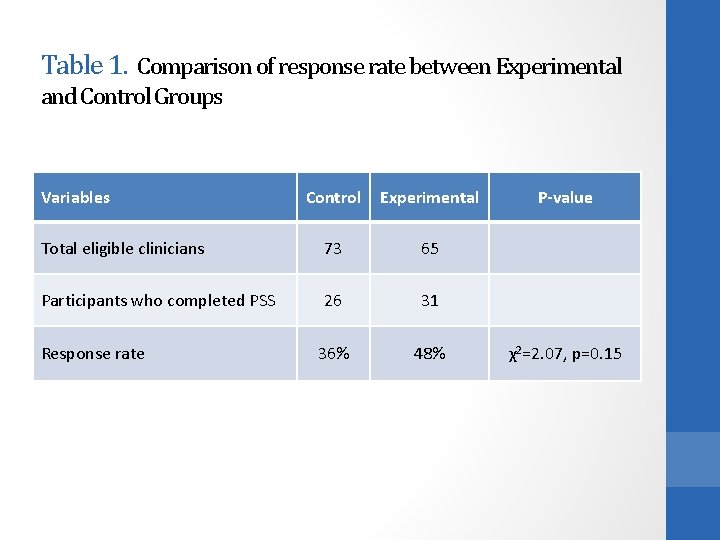

Table 1. Comparison of response rate between Experimental and Control Groups Variables Control Experimental Total eligible clinicians 73 65 Participants who completed PSS 26 31 36% 48% Response rate P-value χ2=2. 07, p=0. 15

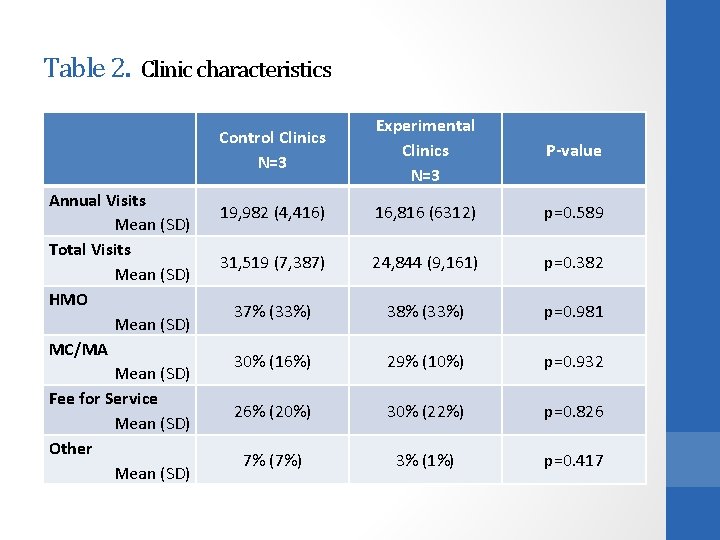

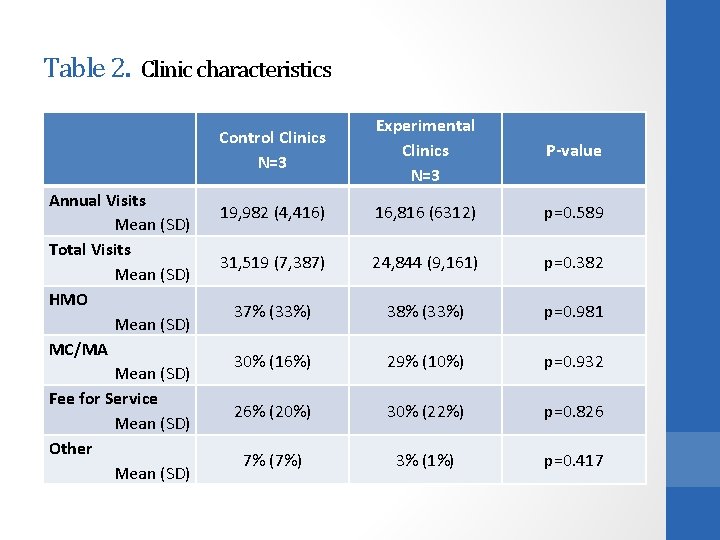

Table 2. Clinic characteristics Annual Visits Mean (SD) Total Visits Mean (SD) HMO Mean (SD) MC/MA Mean (SD) Fee for Service Mean (SD) Other Mean (SD) Control Clinics N=3 Experimental Clinics N=3 P-value 19, 982 (4, 416) 16, 816 (6312) p=0. 589 31, 519 (7, 387) 24, 844 (9, 161) p=0. 382 37% (33%) 38% (33%) p=0. 981 30% (16%) 29% (10%) p=0. 932 26% (20%) 30% (22%) p=0. 826 7% (7%) 3% (1%) p=0. 417

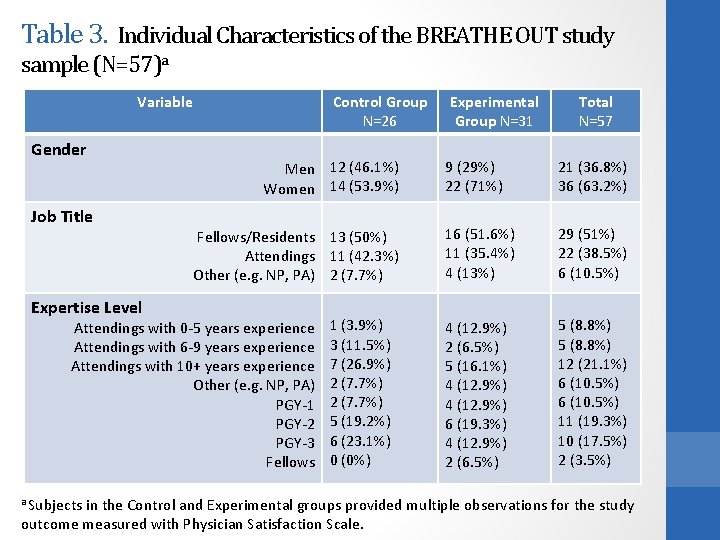

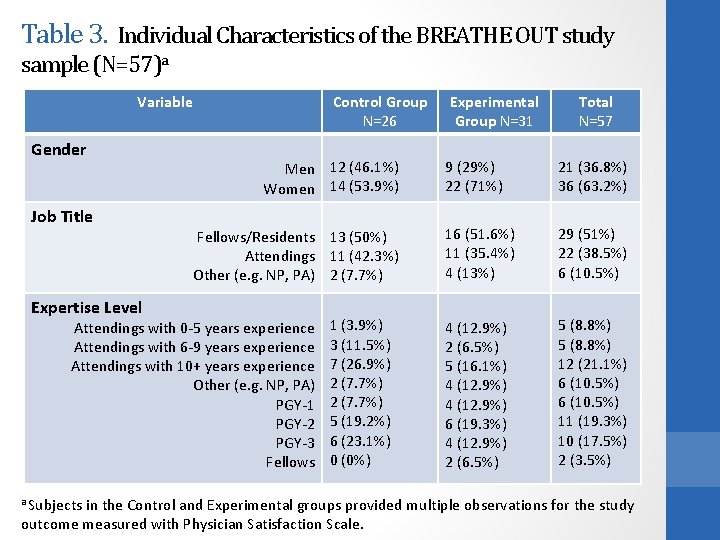

Table 3. Individual Characteristics of the BREATHE OUT study sample (N=57)a Variable Gender Job Title Expertise Level Control Group N=26 Men 12 (46. 1%) Women 14 (53. 9%) Fellows/Residents 13 (50%) Attendings 11 (42. 3%) Other (e. g. NP, PA) 2 (7. 7%) Attendings with 0 -5 years experience Attendings with 6 -9 years experience Attendings with 10+ years experience Other (e. g. NP, PA) PGY-1 PGY-2 PGY-3 Fellows a Subjects 1 (3. 9%) 3 (11. 5%) 7 (26. 9%) 2 (7. 7%) 5 (19. 2%) 6 (23. 1%) 0 (0%) Experimental Group N=31 Total N=57 9 (29%) 22 (71%) 21 (36. 8%) 36 (63. 2%) 16 (51. 6%) 11 (35. 4%) 4 (13%) 29 (51%) 22 (38. 5%) 6 (10. 5%) 4 (12. 9%) 2 (6. 5%) 5 (16. 1%) 4 (12. 9%) 6 (19. 3%) 4 (12. 9%) 2 (6. 5%) 5 (8. 8%) 12 (21. 1%) 6 (10. 5%) 11 (19. 3%) 10 (17. 5%) 2 (3. 5%) in the Control and Experimental groups provided multiple observations for the study outcome measured with Physician Satisfaction Scale.

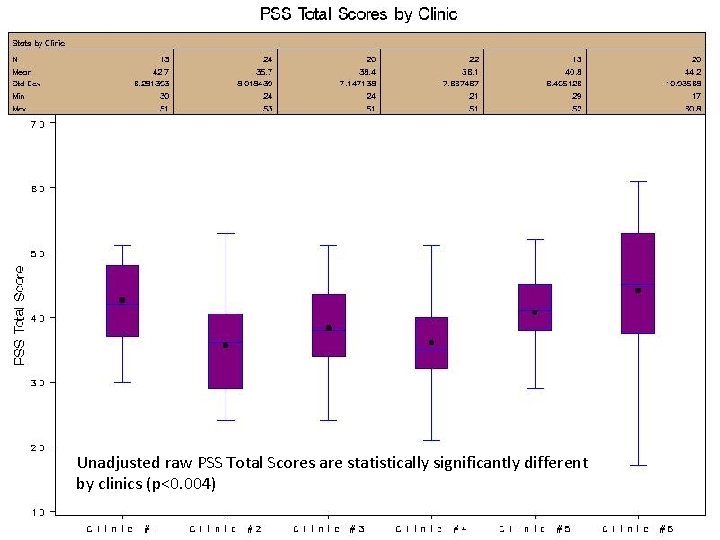

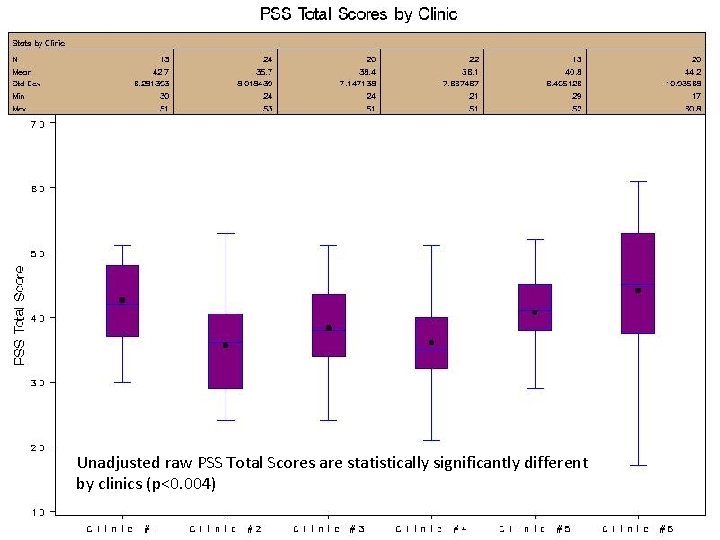

Unadjusted raw PSS Total Scores are statistically significantly different by clinics (p<0. 004)

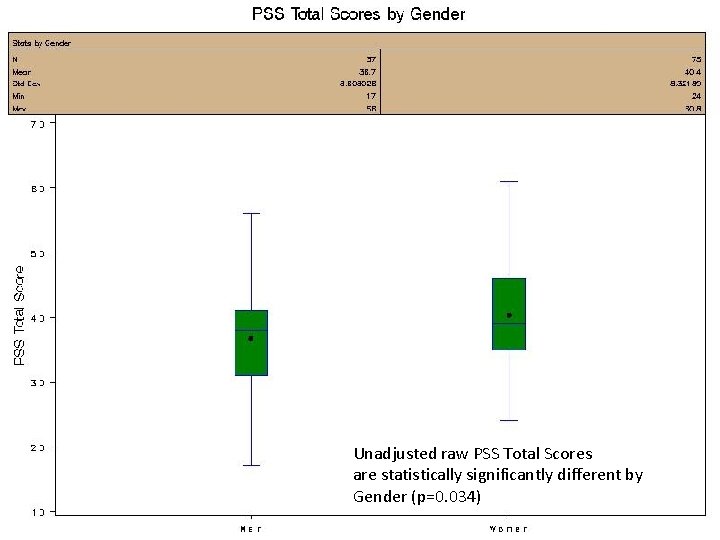

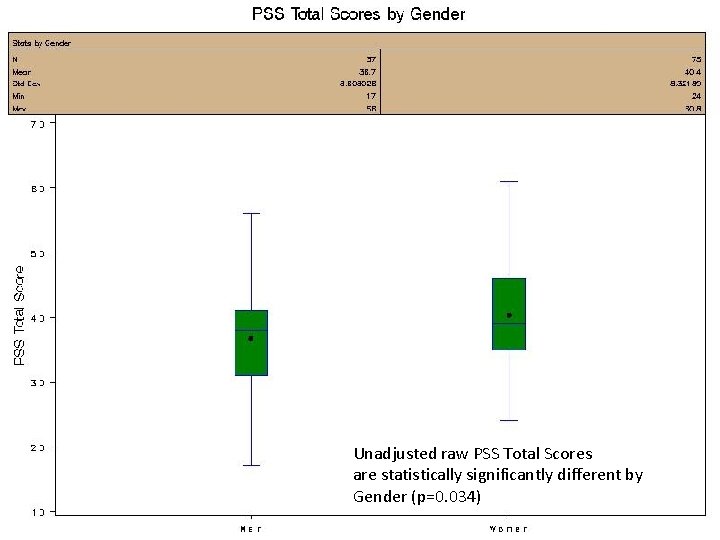

Unadjusted raw PSS Total Scores are statistically significantly different by Gender (p=0. 034)

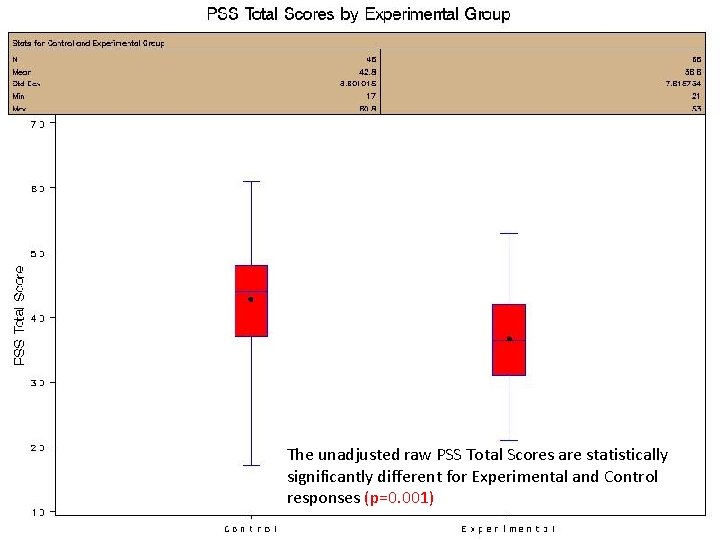

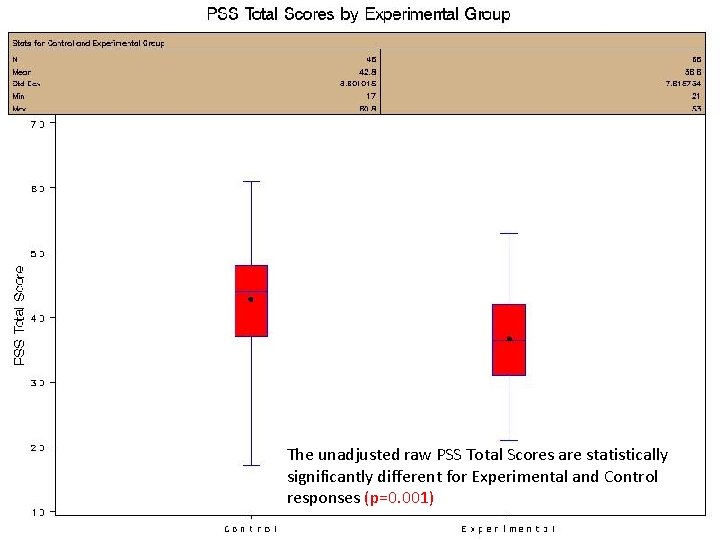

The unadjusted raw PSS Total Scores are statistically significantly different for Experimental and Control responses (p=0. 001)

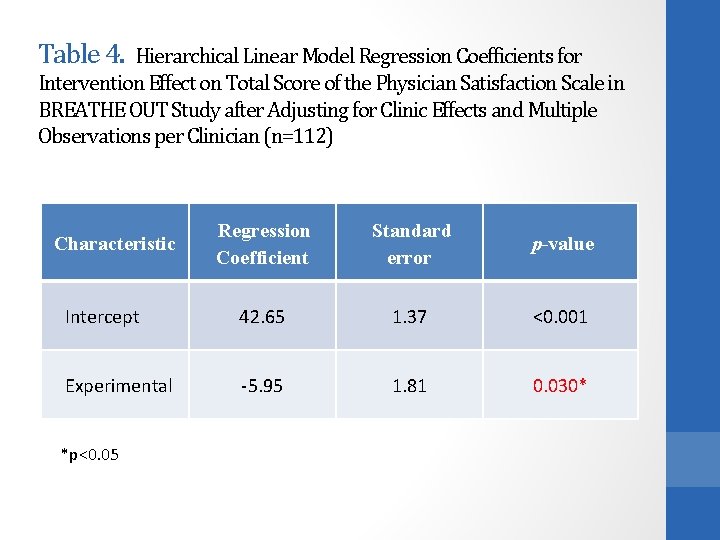

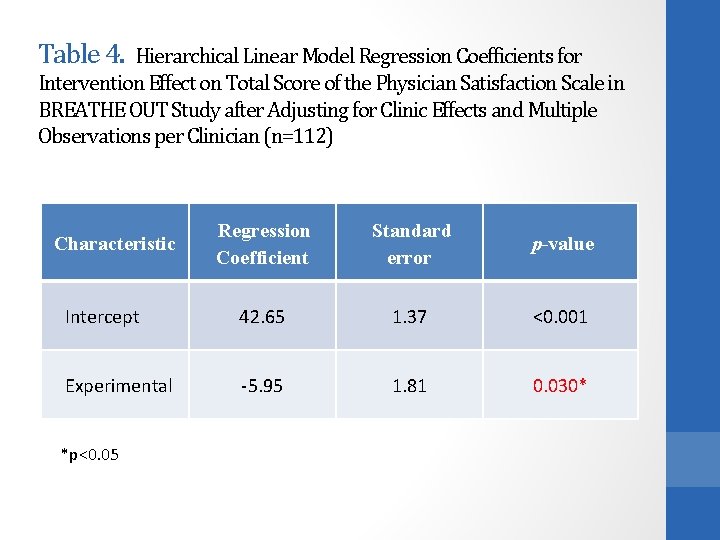

Table 4. Hierarchical Linear Model Regression Coefficients for Intervention Effect on Total Score of the Physician Satisfaction Scale in BREATHE OUT Study after Adjusting for Clinic Effects and Multiple Observations per Clinician (n=112) Regression Coefficient Standard error p-value Intercept 42. 65 1. 37 <0. 001 Experimental -5. 95 1. 81 0. 030* Characteristic *p<0. 05

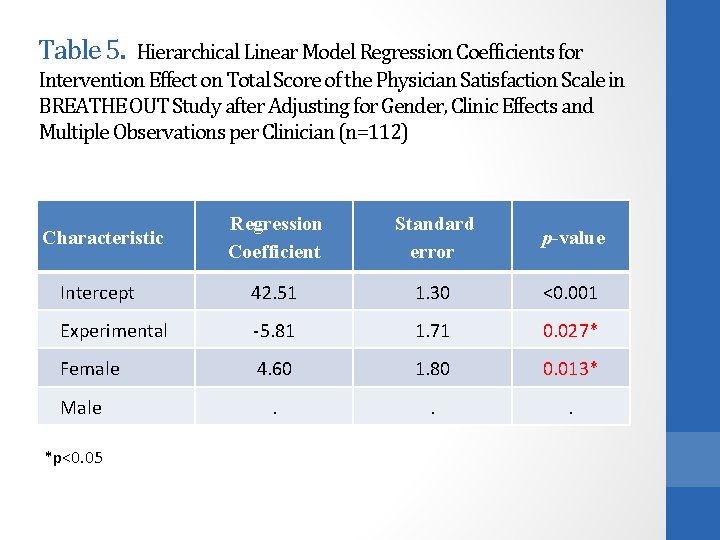

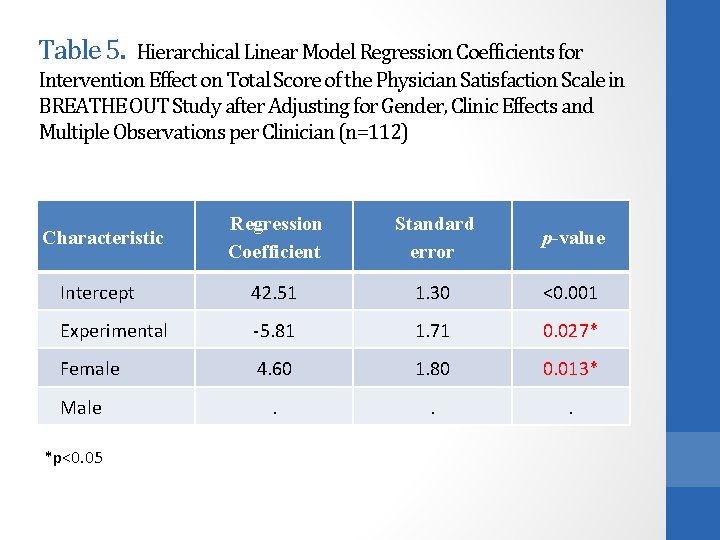

Table 5. Hierarchical Linear Model Regression Coefficients for Intervention Effect on Total Score of the Physician Satisfaction Scale in BREATHE OUT Study after Adjusting for Gender, Clinic Effects and Multiple Observations per Clinician (n=112) Characteristic Regression Coefficient Standard error p-value Intercept 42. 51 1. 30 <0. 001 Experimental -5. 81 1. 71 0. 027* Female 4. 60 1. 80 0. 013* . . . Male *p<0. 05

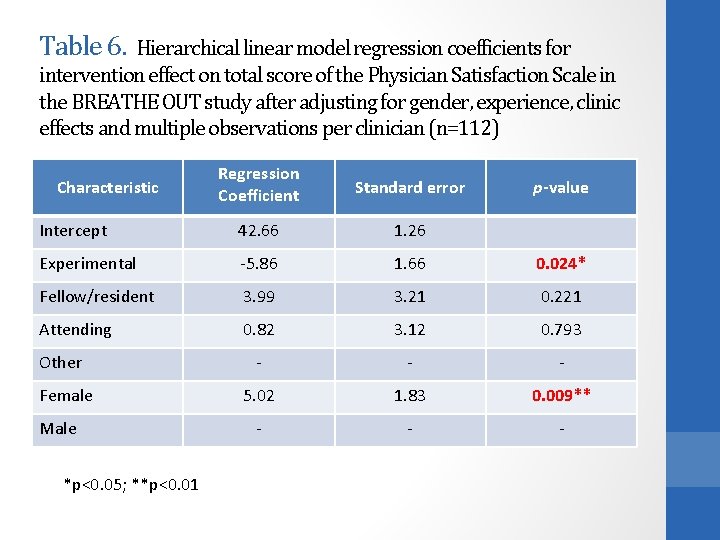

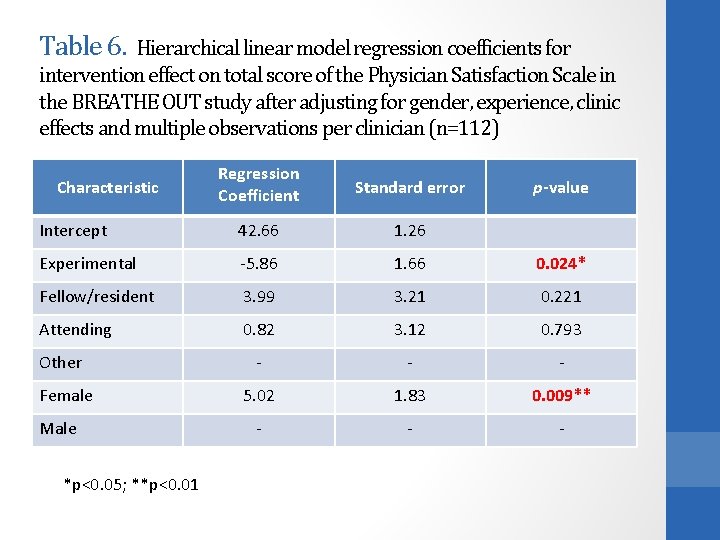

Table 6. Hierarchical linear model regression coefficients for intervention effect on total score of the Physician Satisfaction Scale in the BREATHE OUT study after adjusting for gender, experience, clinic effects and multiple observations per clinician (n=112) Regression Coefficient Standard error Intercept 42. 66 1. 26 Experimental -5. 86 1. 66 0. 024* Fellow/resident 3. 99 3. 21 0. 221 Attending 0. 82 3. 12 0. 793 Other - - - Female 5. 02 1. 83 0. 009** - - - Characteristic Male *p<0. 05; **p<0. 01 p-value

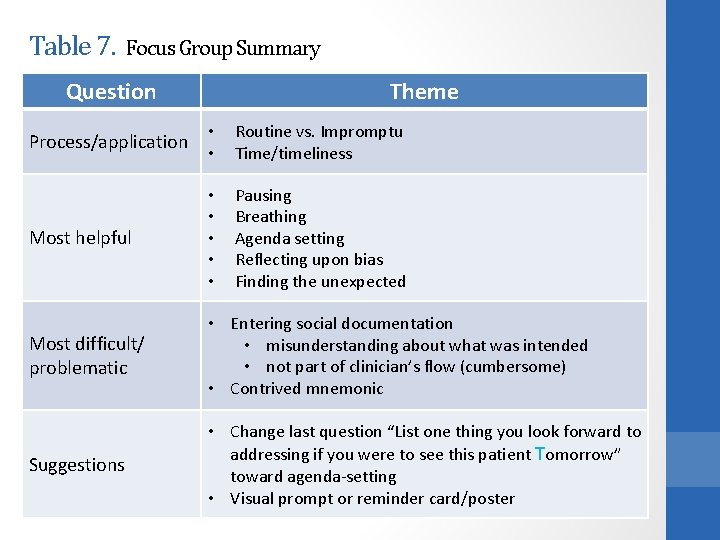

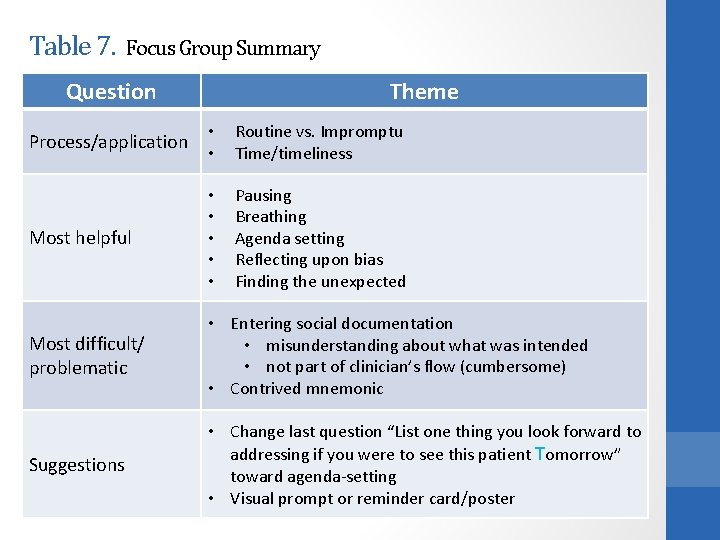

Table 7. Focus Group Summary Question Theme Process/application • • Routine vs. Impromptu Time/timeliness Most helpful • • • Pausing Breathing Agenda setting Reflecting upon bias Finding the unexpected Most difficult/ problematic • Entering social documentation • misunderstanding about what was intended • not part of clinician’s flow (cumbersome) • Contrived mnemonic Suggestions • Change last question “List one thing you look forward to addressing if you were to see this patient Tomorrow” toward agenda-setting • Visual prompt or reminder card/poster

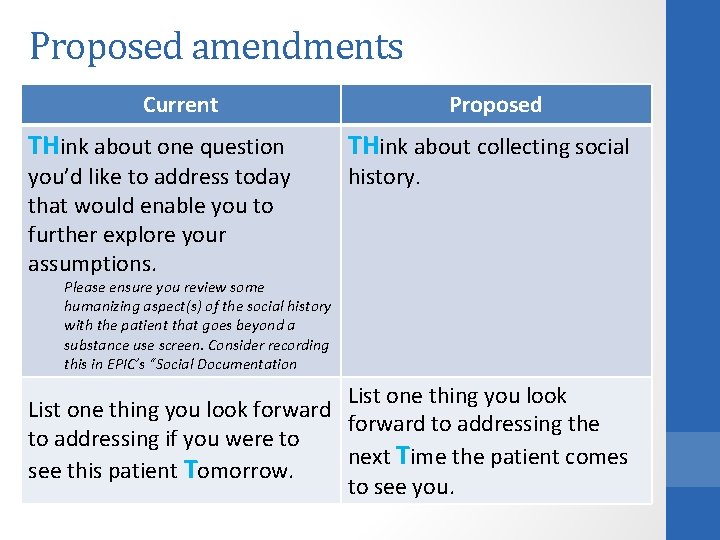

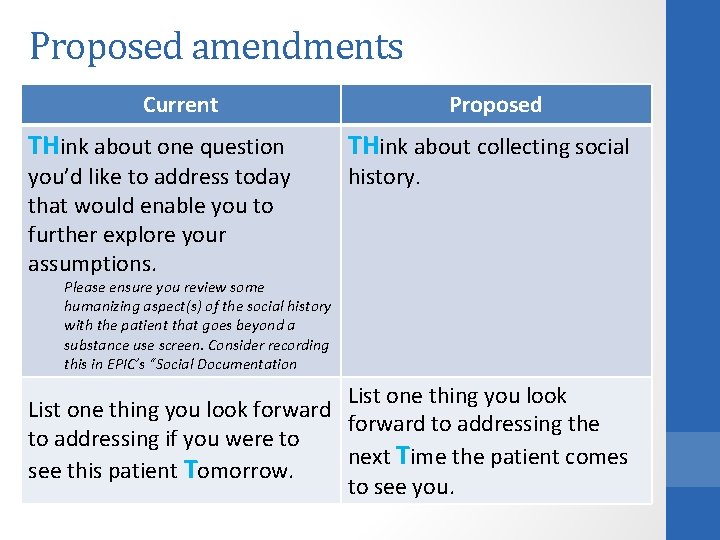

Proposed amendments Current THink about one question you’d like to address today that would enable you to further explore your assumptions. Proposed THink about collecting social history. Please ensure you review some humanizing aspect(s) of the social history with the patient that goes beyond a substance use screen. Consider recording this in EPIC’s “Social Documentation List one thing you look forward to addressing the to addressing if you were to next Time the patient comes see this patient Tomorrow. to see you.

Photo by kristy In summary

Our difficult patients’ perspective • In our study, there was a trend by difficult patients to reporting greater ease of communication with their clinicians. Photo by raybo. B • The discordance in perspectives between clinicians and their “difficult” patients further compels the particular need to intervene on behalf of the clinician.

There is something about gender… Women clinicians rate greater dissatisfaction than men clinicians when encountering patients they consider “difficult. ” Photo by Leo Reynolds Men patients report a harder time talking with their doctor; think they are more difficult for their doctor; and feel less in control of their health care decisions.

Improving our perspective • The BREATHE OUT tool, which prompts clinicians to not only explore who their patients are but also reflect upon themselves, does improve clinician satisfaction across gender and all levels of experience and training. Photo by Tamara van Molken • Next steps: Explore how to integrate this tool on a curricular level for clinical learners.

References • An PG, Rabatin JS, Manwell LB, Linzer M, Brown RL, Schwartz MD Burden of difficult encounters in primary care: data from the minimizing error, maximizing outcomes study. Arch Int Med. 2009; 169: 410 -414. • Ashworth CD, Williamson P, Montano D. A scale to measure physician beliefs about psychosocial aspects of patient care. Soc Sci Med. 1984; 19: 1235 -1238. • Barnett DR, Bass PF, Griffith CH, Caudill S, Wilson J. Determinants of resident satisfaction with patients in their continuity clinic. J Gen Intern Med 2004; 19: 456 -459. • Elder N, Ricer R, Tobias B. How respected family physicians manage difficult patient encounters. JABFM 2006; 19: 533 -541 • Hahn SR. Physical Symptoms and Physician-Experienced Difficulty in the Physician-Patient Relationship. Ann Internal Med. 2001 May 1; 129(9 pt. 2): 897 -904. • Hahn SR, Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, et al. The difficult patient: prevalence, psychopathology and functional impairment. J Gen Intern Med 1996; 11(1): 1 -8. • Hahn SR, Thompson KS, Wills TA et al. The difficult doctor-patient relationship: somatization, personality and psychopathology. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994: 47: 647 -657. • Hinchey, SA, Jackson AL. A cohort study assessing difficult patient encounters in a walk-in primary care clinic, predictors and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2011 Jan 25. [Epub ahead of print] • Jackson JL, Kroenke K. Difficulty patient encounters in the ambulatory clinic. Arch Intern Med. 1999; 159: 1069 -1075. • Mathers N, Jones N, Hannay D. Heartsink patients: a study of their general practitioners. Br. J Gen Pract. 1995; 45(395): 293 -296. • Nin A. The Diary of Anaïs Nin, 1939 -1944. New York, NY: Harcourt Brace & World; 1969. • O’Dowd TC. Five years of heartsink patients in general practice. BMJ 1988; 297(6647): 528 -30. • Schafer S, Nowlis DP. Personalisty disorders among difficult patients. Arch Fam Med. 1998; 7: 126 -129. • Shore BE, Franks P. Physician satisfaction with patient encounters: reliability and validity of an encounterspecific questionnaire. Medical Care. 1986; 24: 580 -589. • Smith RC, Unrecognized responses and feelings of residents and fellows during psychosocial medicine for residents: a controlled study. J Gen Intern Med 1986; 61: 982. • All photos from Flickr Creative Commons

Thank you! • Larissa Zakletskaia, senior analyst UW DFM • Mary Beth Plane, former research director of UW DFM • Dr. Mindy Smith, DFM consultant • University of Wisconsin Department of Family Medicine who provided a small departmental grant

Questions? BREATHE OUT Photo by unbearable lightness