Selfinterest through delegation An alternative motivation for the

- Slides: 22

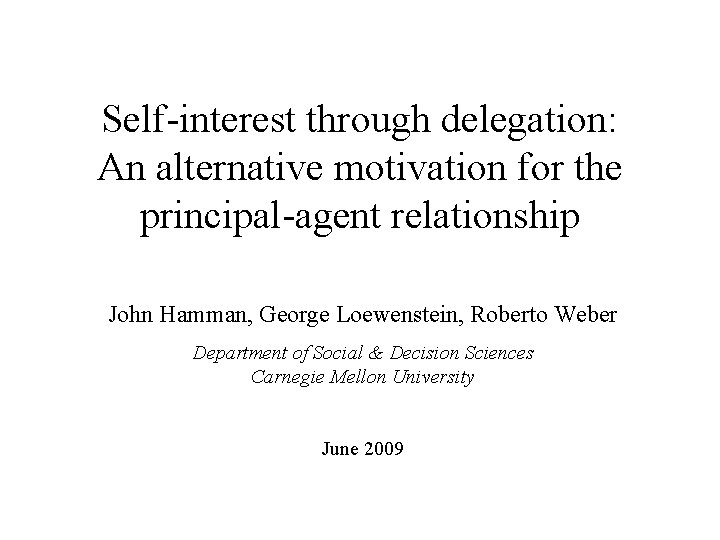

Self-interest through delegation: An alternative motivation for the principal-agent relationship John Hamman, George Loewenstein, Roberto Weber Department of Social & Decision Sciences Carnegie Mellon University June 2009

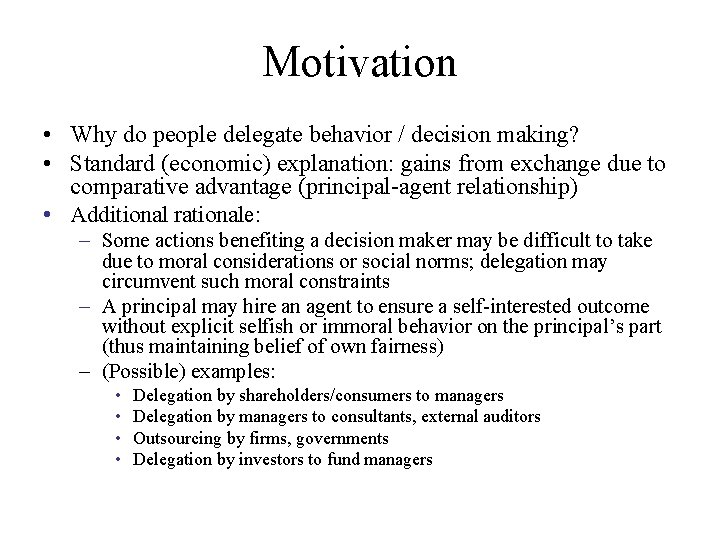

Motivation • Why do people delegate behavior / decision making? • Standard (economic) explanation: gains from exchange due to comparative advantage (principal-agent relationship) • Additional rationale: – Some actions benefiting a decision maker may be difficult to take due to moral considerations or social norms; delegation may circumvent such moral constraints – A principal may hire an agent to ensure a self-interested outcome without explicit selfish or immoral behavior on the principal’s part (thus maintaining belief of own fairness) – (Possible) examples: • • Delegation by shareholders/consumers to managers Delegation by managers to consultants, external auditors Outsourcing by firms, governments Delegation by investors to fund managers

Relevant Literature • People exhibit other-regarding behavior consistent with fairness or social welfare preferences (Forsythe et al. , 1994; Hoffman et al. , 1994; Fehr and Schmidt, 1999; Bolton and Ockenfels, 2000; Charness and Rabin, 2002) • But perhaps people value self-image rather than fairness per se (Konow, 2000; Murnighan, Oesch and Pillutla, 2001; Benabou and Tirole, 2006) • Given the opportunity to implement unfair outcomes without explicitly doing so themselves (“moral wiggle room”), many people do so (Dana, Weber, and Kuang, 2007; Dana, Cain, and Dawes, 2006; Lazear, Malmendier and Weber, 2007) • Diffusion of responsibility can also mitigate pro-social behavior (Latane and Darley, 1968; Darley and Latane, 1968; Dana, Weber, and Kuang, 2007) • Third-party agents bring higher earnings in bargaining (Katz, 1991; Schotter, Zheng, and Snyder, 2000; Fershtman and Gneezy, 2001) • Those affected and third parties are less likely to punish delegation (Bartling & Fischbacher 2008; Coffman 2008)

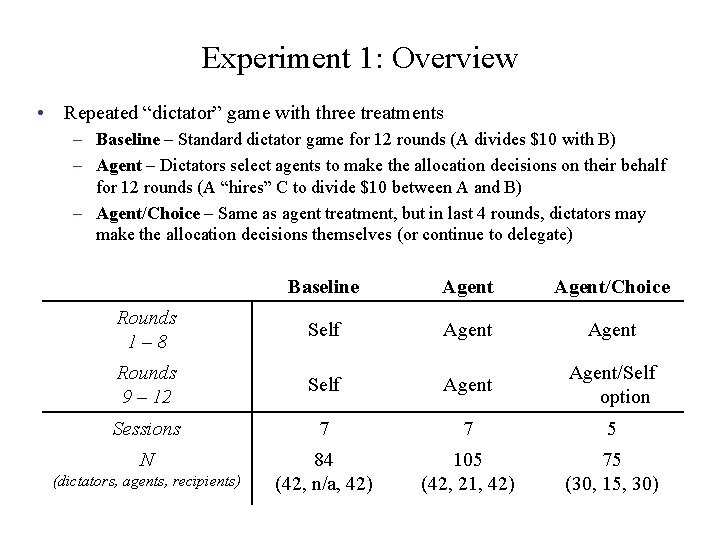

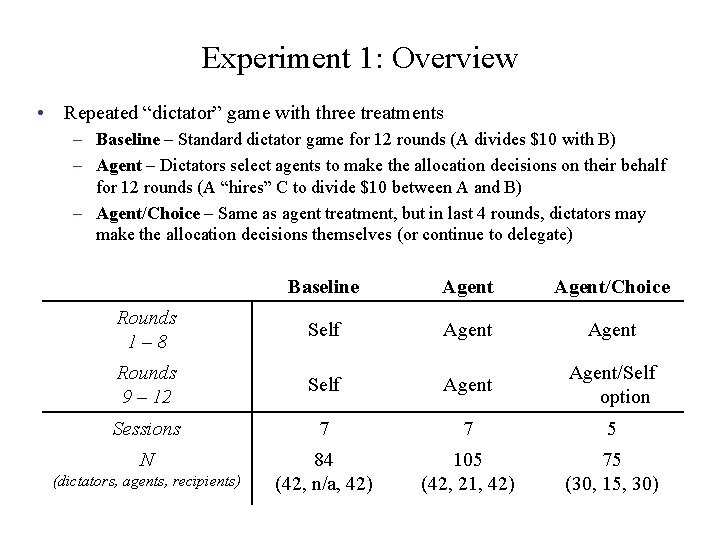

Experiment 1: Overview • Repeated “dictator” game with three treatments – Baseline – Standard dictator game for 12 rounds (A divides $10 with B) – Agent – Dictators select agents to make the allocation decisions on their behalf for 12 rounds (A “hires” C to divide $10 between A and B) – Agent/Choice – Same as agent treatment, but in last 4 rounds, dictators may make the allocation decisions themselves (or continue to delegate) Baseline Agent/Choice Rounds 1– 8 Self Agent Rounds 9 – 12 Self Agent/Self option Sessions 7 7 5 N 84 (42, n/a, 42) 105 (42, 21, 42) 75 (30, 15, 30) (dictators, agents, recipients)

Experiment 1: Main Predictions • Principals (dictators) will share money with recipients when they give directly (baseline) than when they hire agents to give on their behalf (agent treatments) • Principals will switch away from agents who share significant amounts to agents who share little or nothing • Self-report scores reflect diminished feelings of responsibility for unfair outcomes when acting through agents?

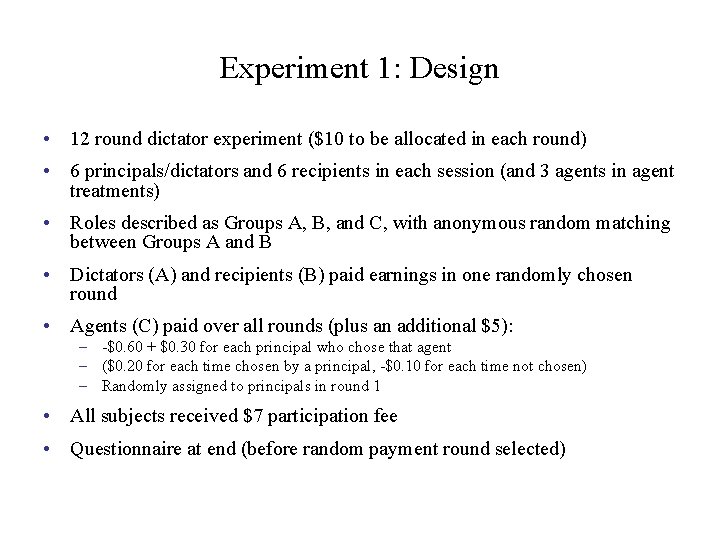

Experiment 1: Design • 12 round dictator experiment ($10 to be allocated in each round) • 6 principals/dictators and 6 recipients in each session (and 3 agents in agent treatments) • Roles described as Groups A, B, and C, with anonymous random matching between Groups A and B • Dictators (A) and recipients (B) paid earnings in one randomly chosen round • Agents (C) paid over all rounds (plus an additional $5): – -$0. 60 + $0. 30 for each principal who chose that agent – ($0. 20 for each time chosen by a principal, -$0. 10 for each time not chosen) – Randomly assigned to principals in round 1 • All subjects received $7 participation fee • Questionnaire at end (before random payment round selected)

Mean Amount Shared per Round

Mean Amount Shared per Round

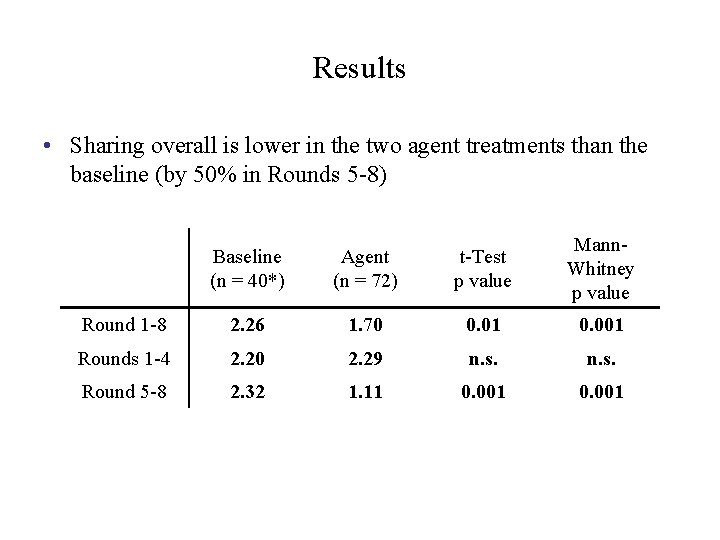

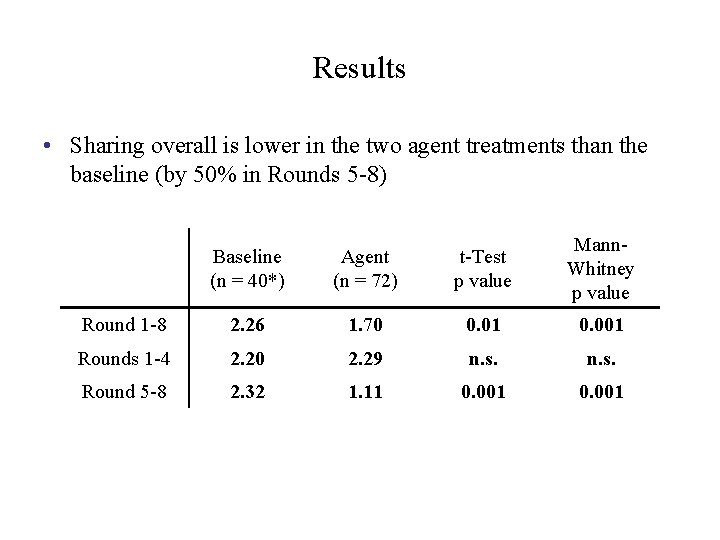

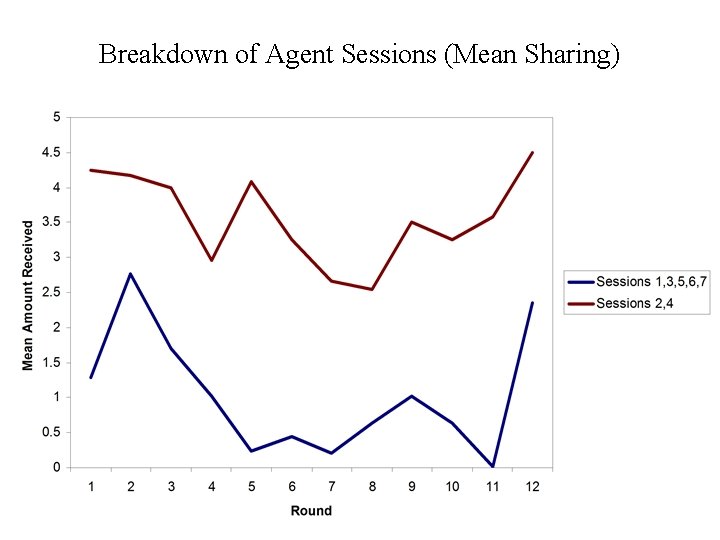

Results • Sharing overall is lower in the two agent treatments than the baseline (by 50% in Rounds 5 -8) Mannt-Test Whitney p value Baseline (n = 40*) Agent (n = 72) Round 1 -8 2. 26 1. 70 0. 01 0. 001 Rounds 1 -4 2. 20 2. 29 n. s. Round 5 -8 2. 32 1. 11 0. 001

Switching in rounds 2 – 8 (switching in round t based on amount shared in t-1)

Mean Amount Shared per Round

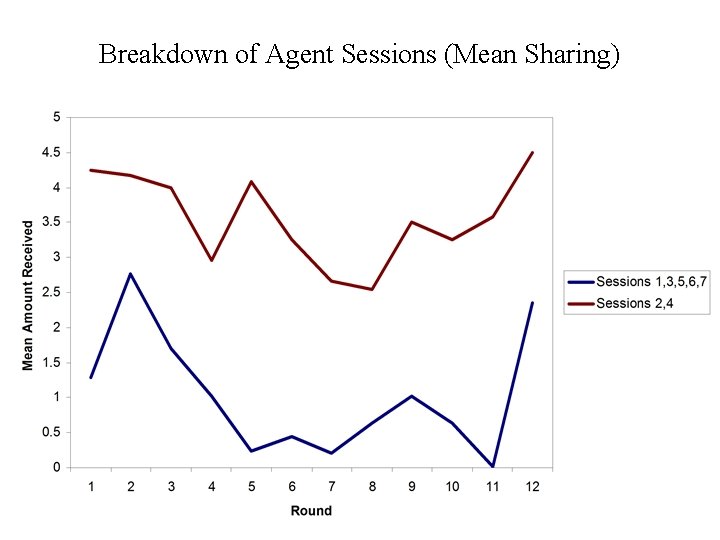

Breakdown of Agent Sessions (Mean Sharing)

Mean Amount Shared per Round

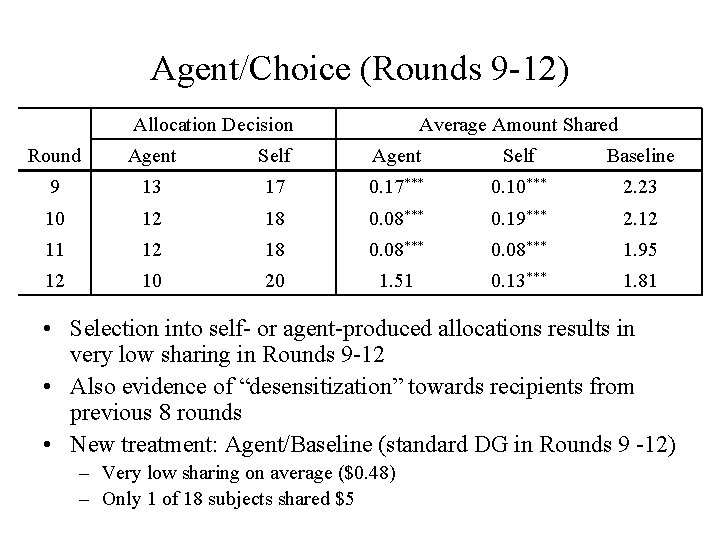

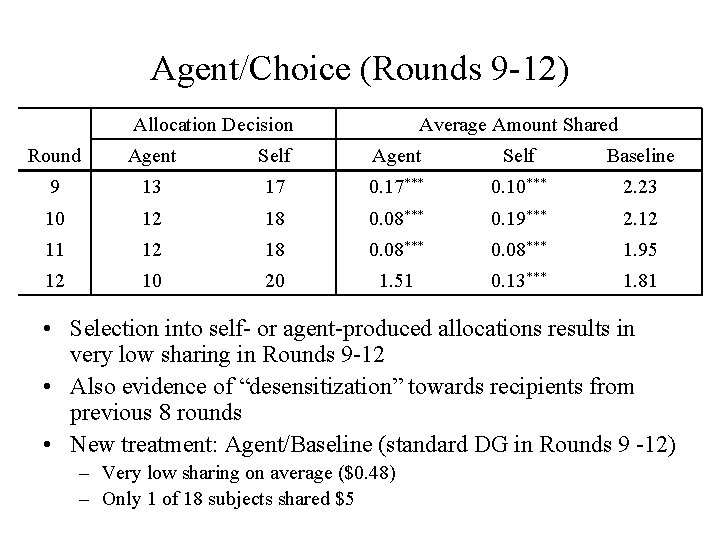

Agent/Choice (Rounds 9 -12) Allocation Decision Average Amount Shared Round Agent Self Baseline 9 13 17 0. 17*** 0. 10*** 2. 23 10 12 18 0. 08*** 0. 19*** 2. 12 11 12 18 0. 08*** 1. 95 12 10 20 1. 51 0. 13*** 1. 81 • Selection into self- or agent-produced allocations results in very low sharing in Rounds 9 -12 • Also evidence of “desensitization” towards recipients from previous 8 rounds • New treatment: Agent/Baseline (standard DG in Rounds 9 -12) – Very low sharing on average ($0. 48) – Only 1 of 18 subjects shared $5

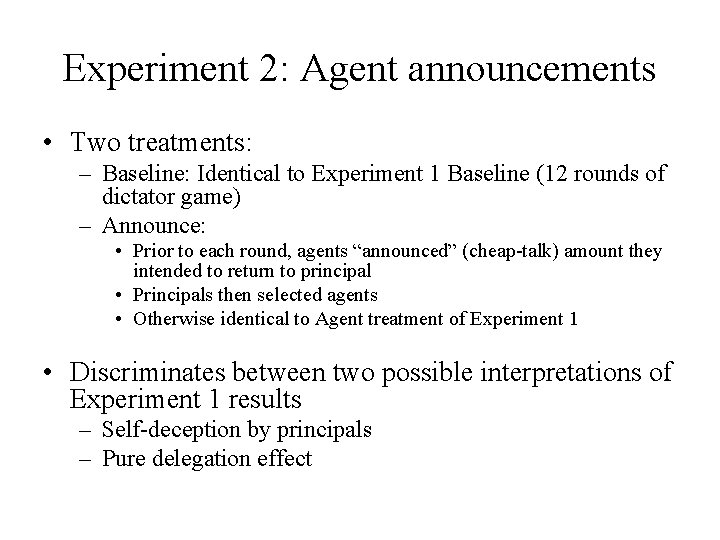

Experiment 2: Agent announcements • Two treatments: – Baseline: Identical to Experiment 1 Baseline (12 rounds of dictator game) – Announce: • Prior to each round, agents “announced” (cheap-talk) amount they intended to return to principal • Principals then selected agents • Otherwise identical to Agent treatment of Experiment 1 • Discriminates between two possible interpretations of Experiment 1 results – Self-deception by principals – Pure delegation effect

Results: Experiment 2

Results: Experiment 2

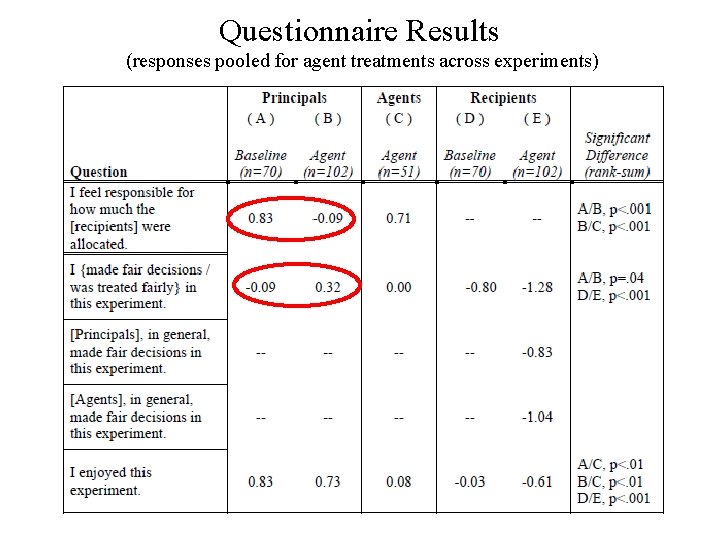

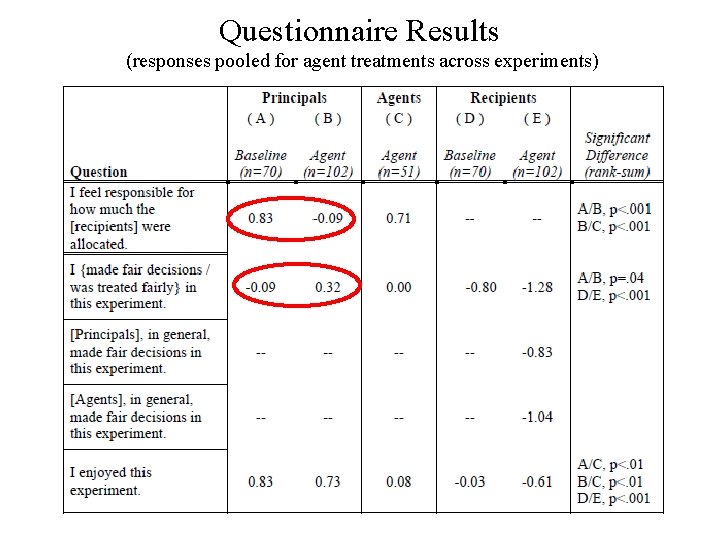

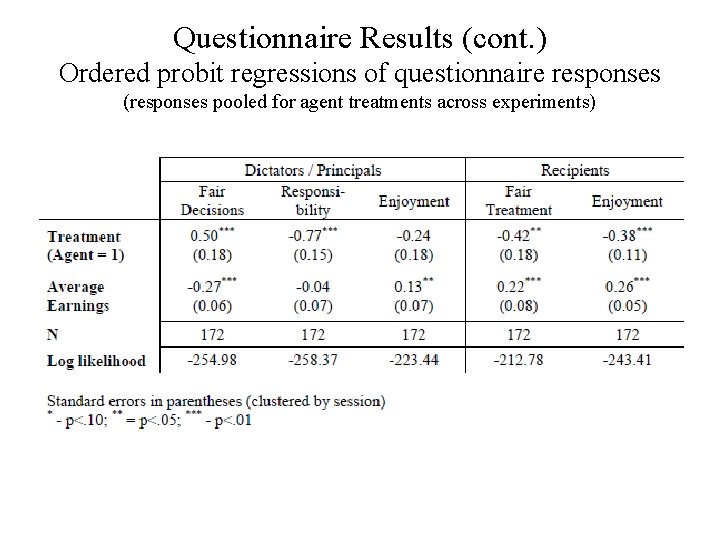

Questionnaire Results (responses pooled for agent treatments across experiments)

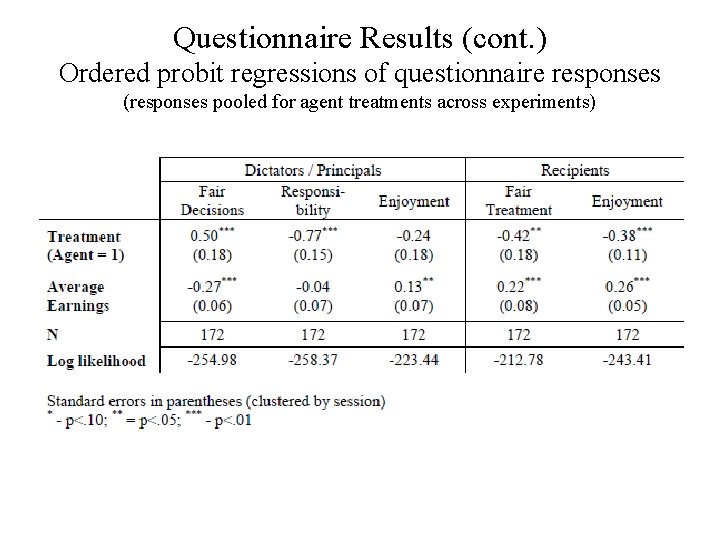

Questionnaire Results (cont. ) Ordered probit regressions of questionnaire responses (responses pooled for agent treatments across experiments)

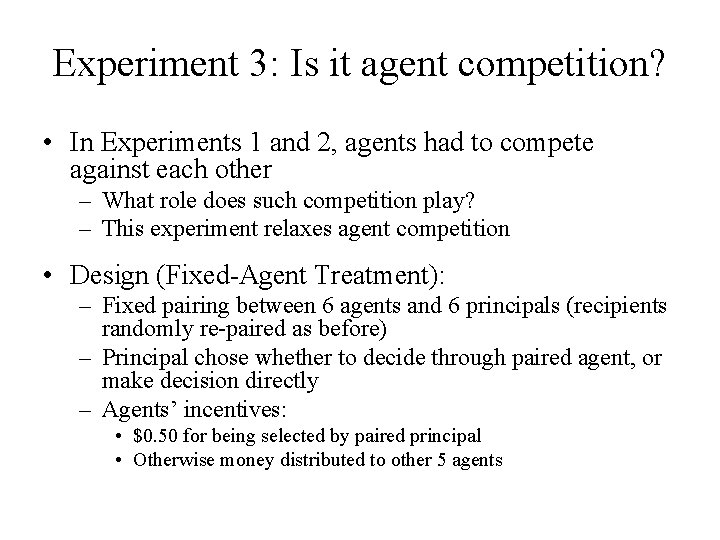

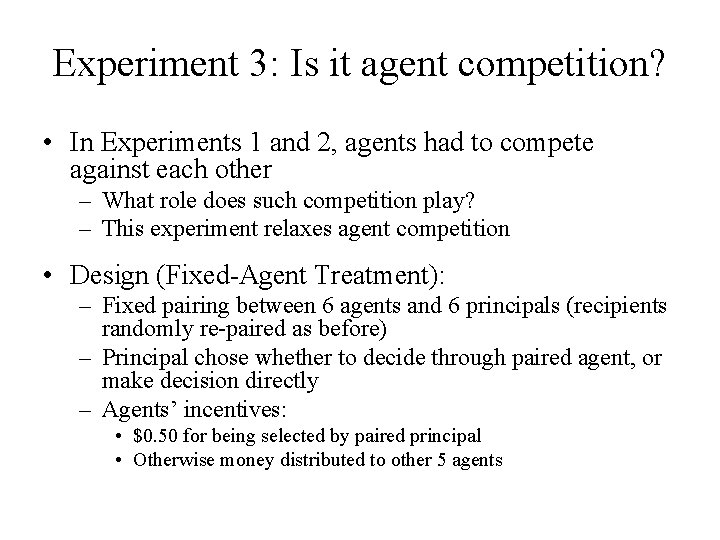

Experiment 3: Is it agent competition? • In Experiments 1 and 2, agents had to compete against each other – What role does such competition play? – This experiment relaxes agent competition • Design (Fixed-Agent Treatment): – Fixed pairing between 6 agents and 6 principals (recipients randomly re-paired as before) – Principal chose whether to decide through paired agent, or make decision directly – Agents’ incentives: • $0. 50 for being selected by paired principal • Otherwise money distributed to other 5 agents

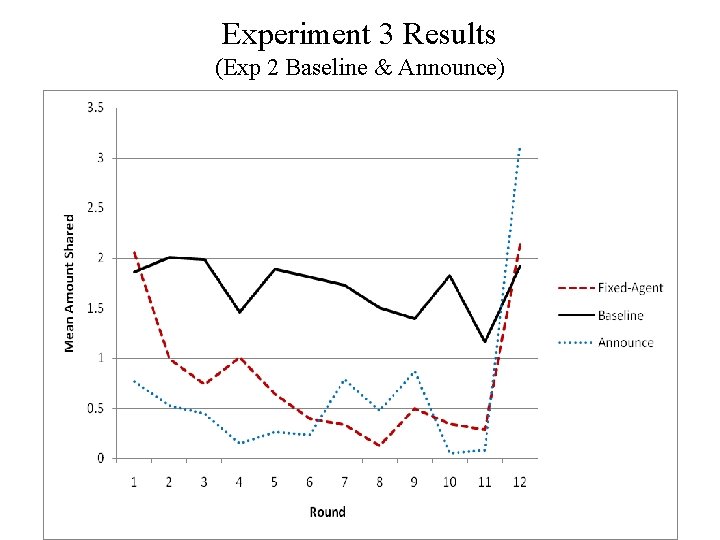

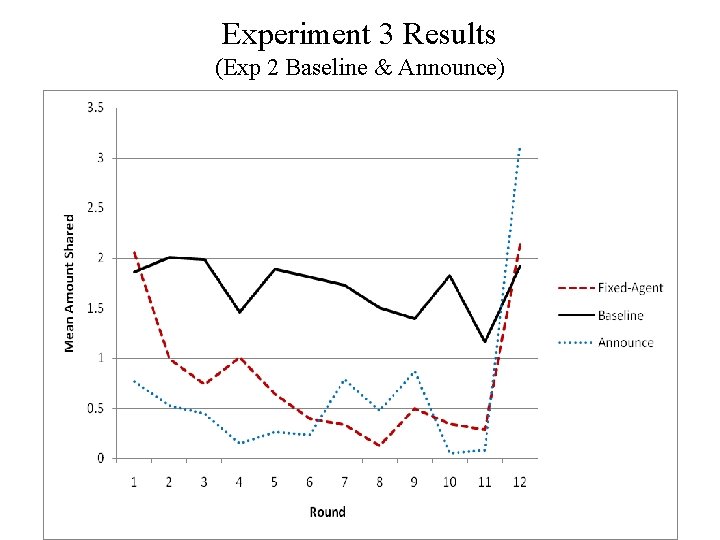

Experiment 3 Results (Exp 2 Baseline & Announce)

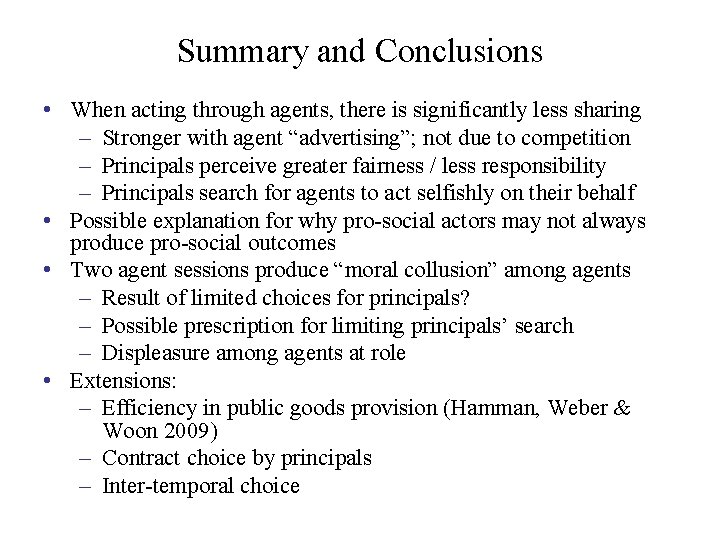

Summary and Conclusions • When acting through agents, there is significantly less sharing – Stronger with agent “advertising”; not due to competition – Principals perceive greater fairness / less responsibility – Principals search for agents to act selfishly on their behalf • Possible explanation for why pro-social actors may not always produce pro-social outcomes • Two agent sessions produce “moral collusion” among agents – Result of limited choices for principals? – Possible prescription for limiting principals’ search – Displeasure among agents at role • Extensions: – Efficiency in public goods provision (Hamman, Weber & Woon 2009) – Contract choice by principals – Inter-temporal choice