Revisiting collocational priming Foundations integrating corpus and psycholinguistic

![[The shift to color vision in primates] may be related to changes in the [The shift to color vision in primates] may be related to changes in the](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/1fd4306995ae44f24a375b874417ebaa/image-38.jpg)

- Slides: 45

Revisiting collocational priming

Foundations: integrating corpus and psycholinguistic research

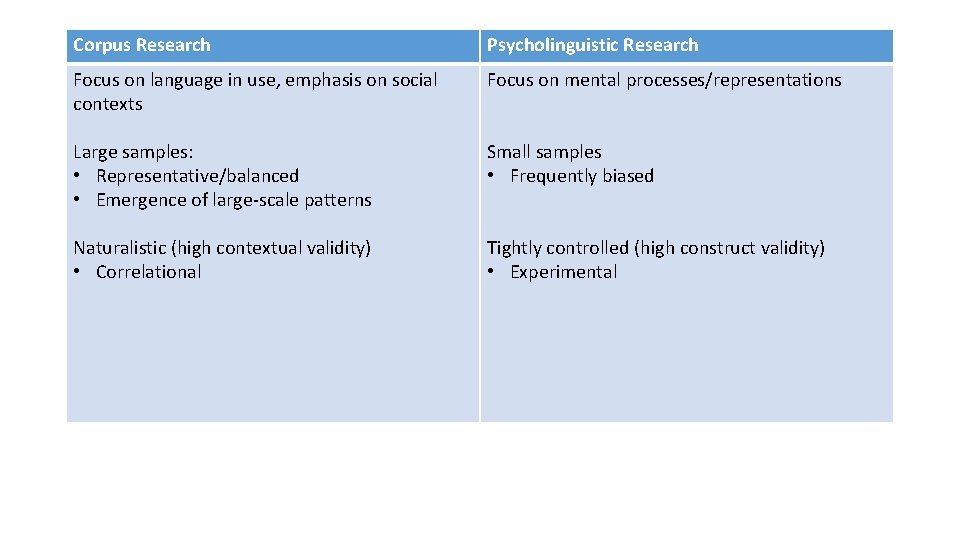

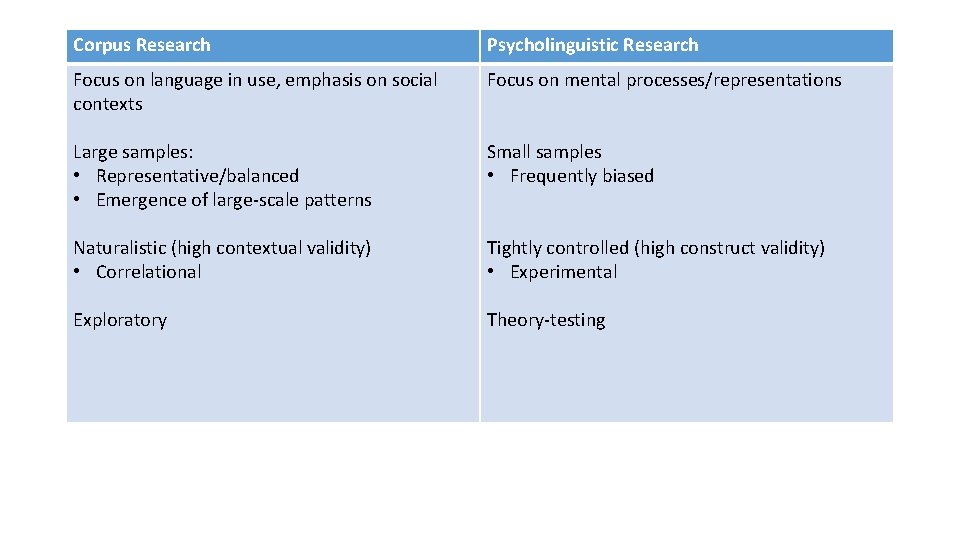

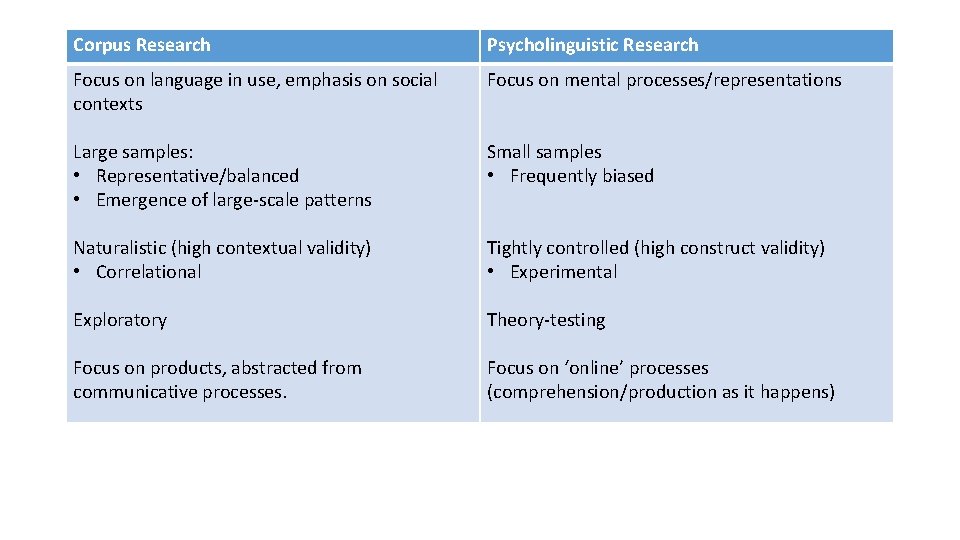

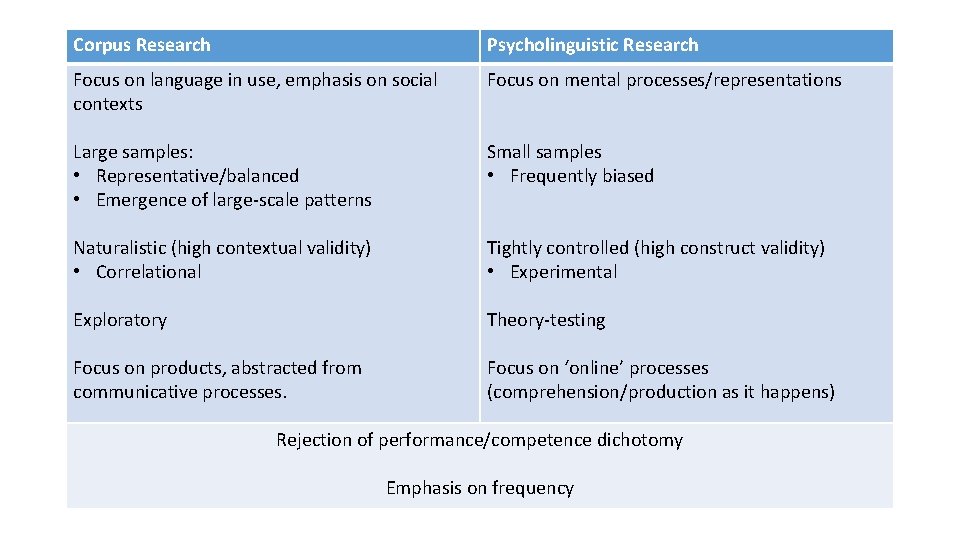

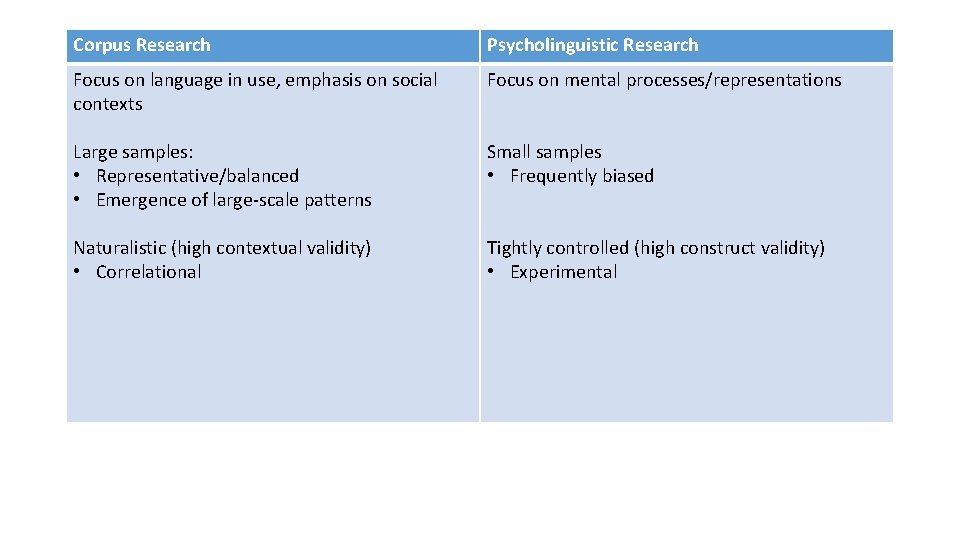

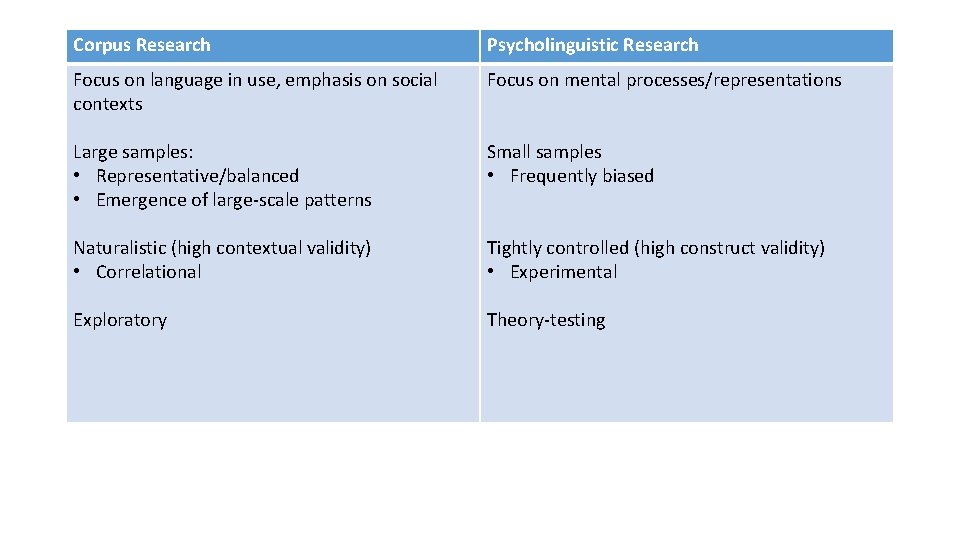

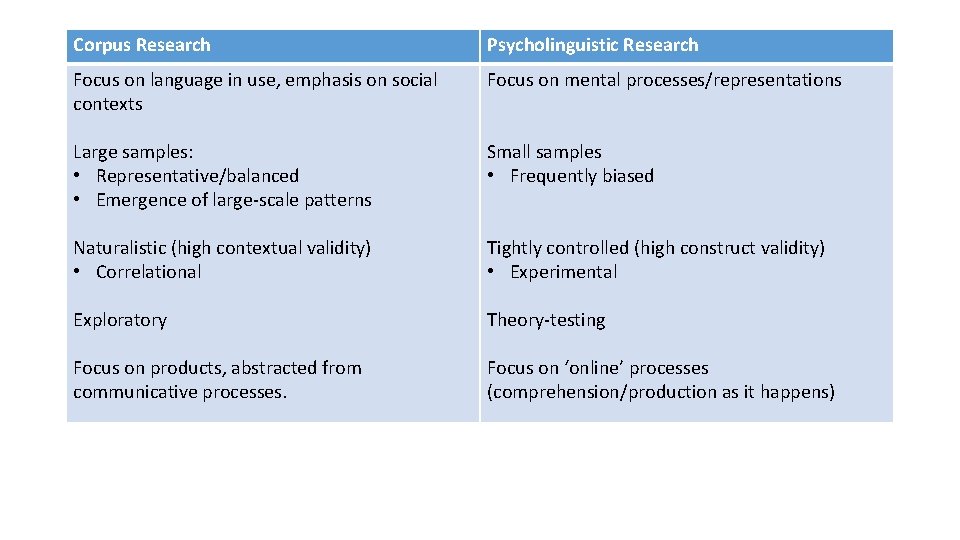

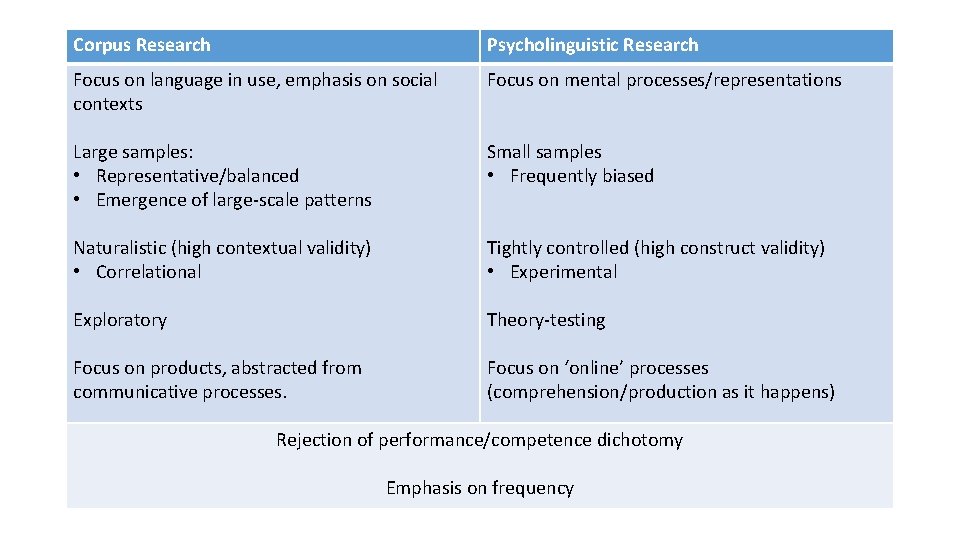

Corpus Research Psycholinguistic Research Focus on language in use, emphasis on social contexts Focus on mental processes/representations

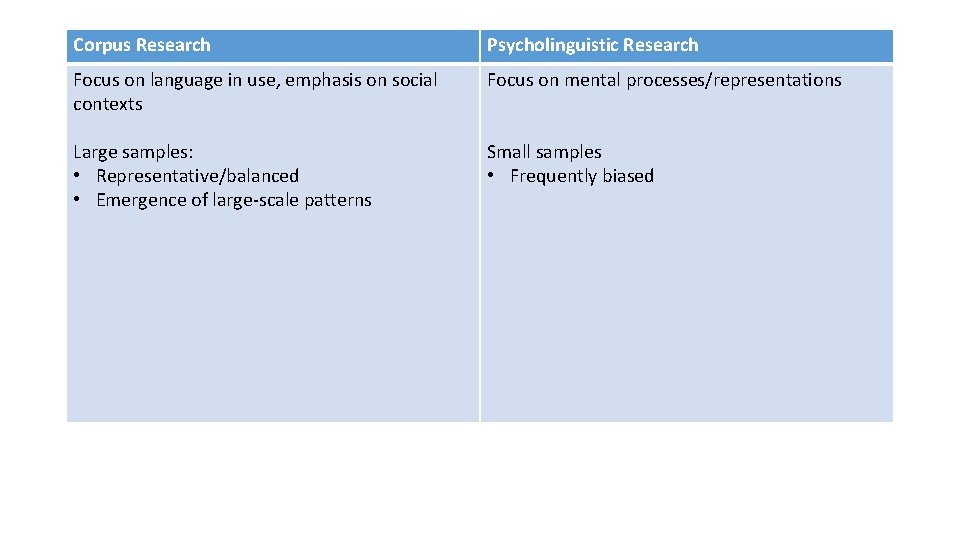

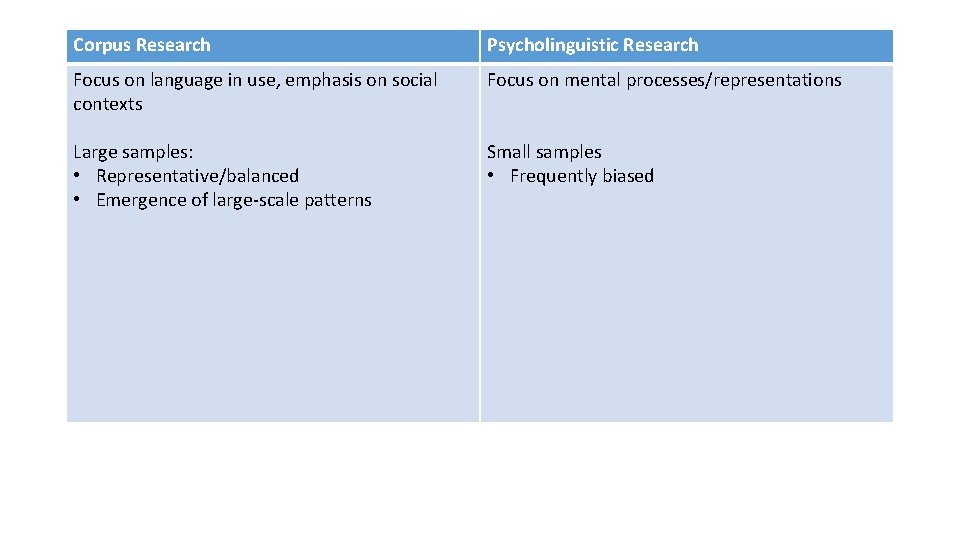

Corpus Research Psycholinguistic Research Focus on language in use, emphasis on social contexts Focus on mental processes/representations Large samples: • Representative/balanced • Emergence of large-scale patterns Small samples • Frequently biased

Corpus Research Psycholinguistic Research Focus on language in use, emphasis on social contexts Focus on mental processes/representations Large samples: • Representative/balanced • Emergence of large-scale patterns Small samples • Frequently biased Naturalistic (high contextual validity) • Correlational Tightly controlled (high construct validity) • Experimental

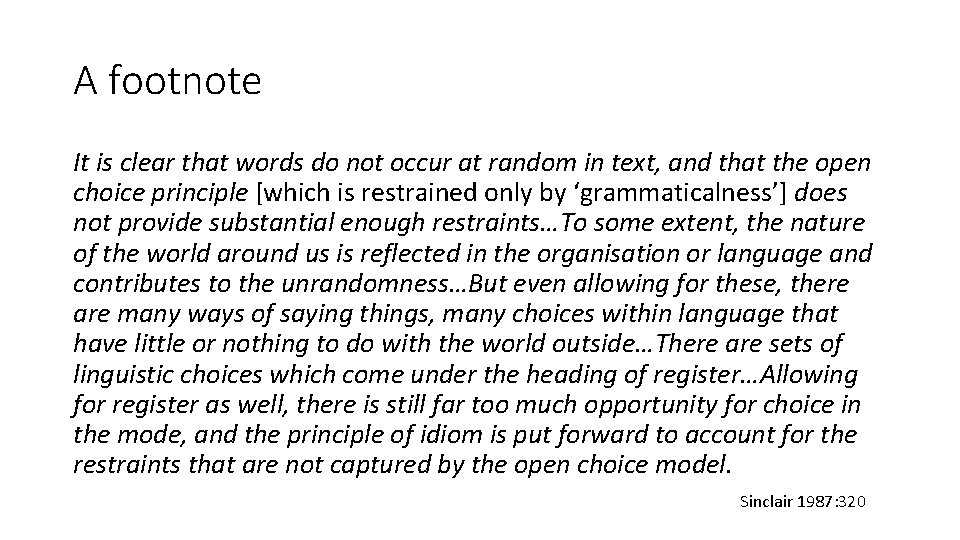

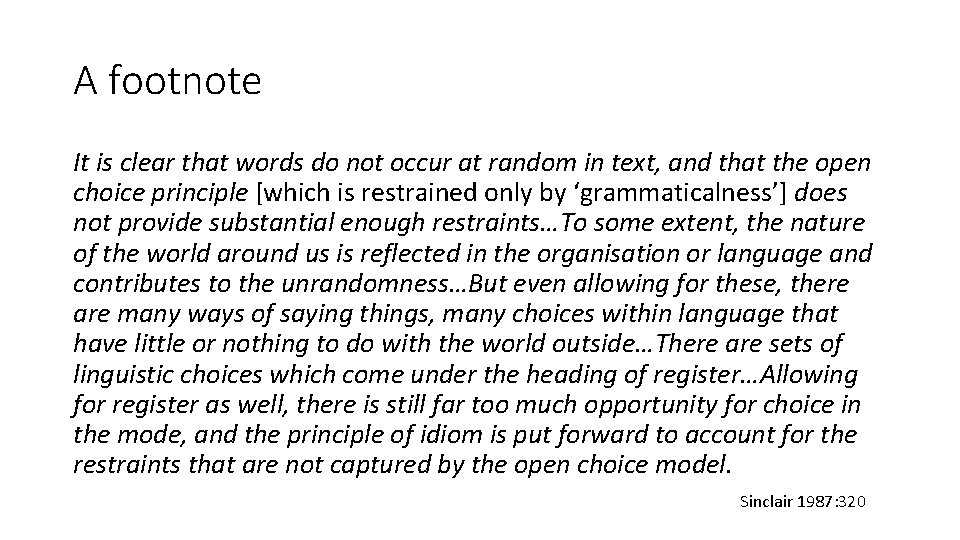

A footnote It is clear that words do not occur at random in text, and that the open choice principle [which is restrained only by ‘grammaticalness’] does not provide substantial enough restraints…To some extent, the nature of the world around us is reflected in the organisation or language and contributes to the unrandomness…But even allowing for these, there are many ways of saying things, many choices within language that have little or nothing to do with the world outside…There are sets of linguistic choices which come under the heading of register…Allowing for register as well, there is still far too much opportunity for choice in the mode, and the principle of idiom is put forward to account for the restraints that are not captured by the open choice model. Sinclair 1987: 320

Corpus Research Psycholinguistic Research Focus on language in use, emphasis on social contexts Focus on mental processes/representations Large samples: • Representative/balanced • Emergence of large-scale patterns Small samples • Frequently biased Naturalistic (high contextual validity) • Correlational Tightly controlled (high construct validity) • Experimental Exploratory Theory-testing

Corpus Research Psycholinguistic Research Focus on language in use, emphasis on social contexts Focus on mental processes/representations Large samples: • Representative/balanced • Emergence of large-scale patterns Small samples • Frequently biased Naturalistic (high contextual validity) • Correlational Tightly controlled (high construct validity) • Experimental Exploratory Theory-testing Focus on products, abstracted from communicative processes. Focus on ‘online’ processes (comprehension/production as it happens)

Corpus Research Psycholinguistic Research Focus on language in use, emphasis on social contexts Focus on mental processes/representations Large samples: • Representative/balanced • Emergence of large-scale patterns Small samples • Frequently biased Naturalistic (high contextual validity) • Correlational Tightly controlled (high construct validity) • Experimental Exploratory Theory-testing Focus on products, abstracted from communicative processes. Focus on ‘online’ processes (comprehension/production as it happens) Rejection of performance/competence dichotomy Emphasis on frequency

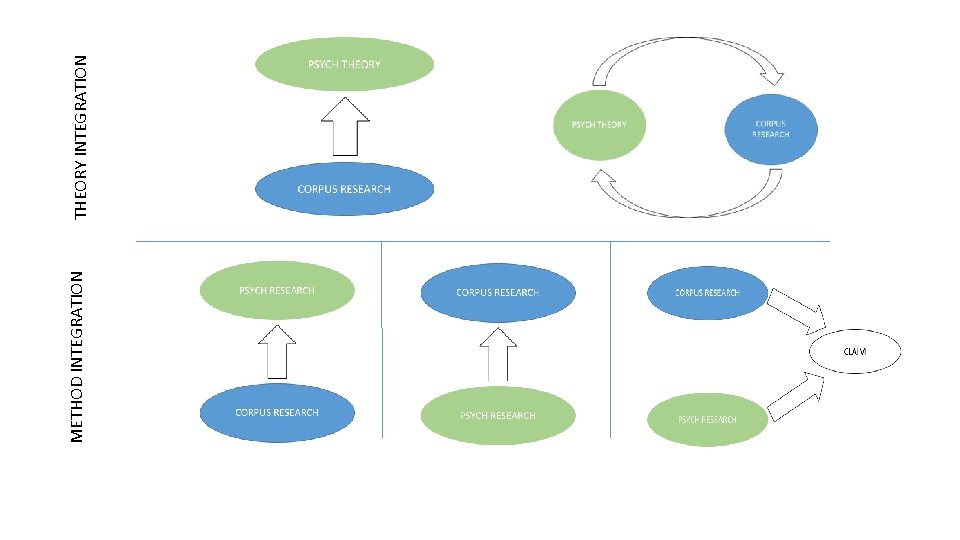

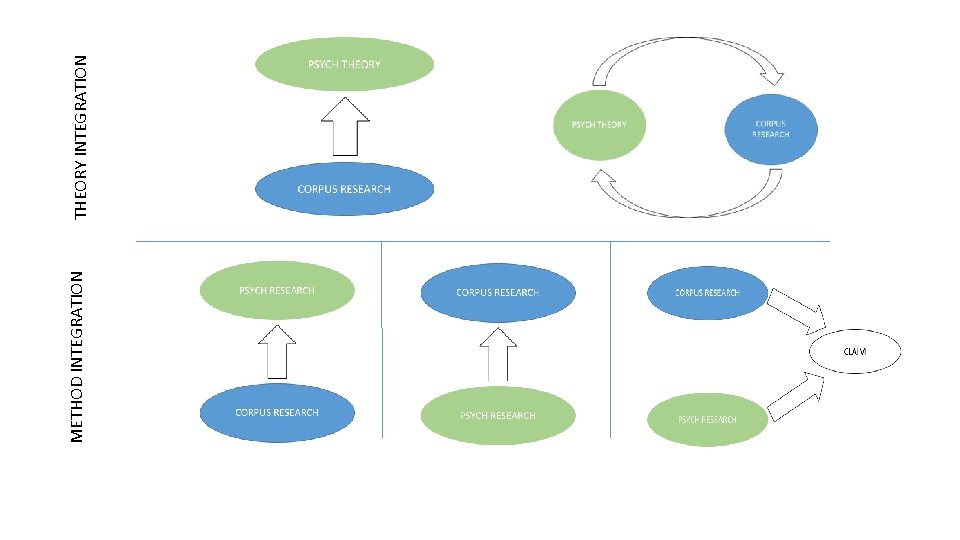

METHOD INTEGRATION THEORY INTEGRATION

Durrant & Doherty 2010

Background to Durrant & Doherty 2010 • Frequent collocations as a phenomenon of interest • Priming as a psycholinguistic mechanism for collocation (Hoey, 2005)

Hoey’s corpus-psycholinguistic integration Model Potential Issues • Introjection (Lamb, 2000) • Relevance of corpus data to individuals’ experience

’Priming’ as a model of collocation processing • Recognition of a word is facilitated by its preceding context (Meyer & Schvaneveldt, 1971) • Found between: • Words with similar spelling/pronunciation • Words related in meaning • Syntactically congruous words (e. g. determiner, noun) • Two-stage task: • View prime word • View target string; make word/nonword decision/read word • Automatic vs. strategic priming • Evidence of priming between associated words, some of which are collocations

Key questions • Does psycholinguistic priming exist between high-frequency collocations in general (not just associates)? • Does priming happen at the automatic or strategic level?

Durrant & Doherty’s integration Model Potential Issues • Relevance of corpus data to individuals’ experience • Coherence of constructs

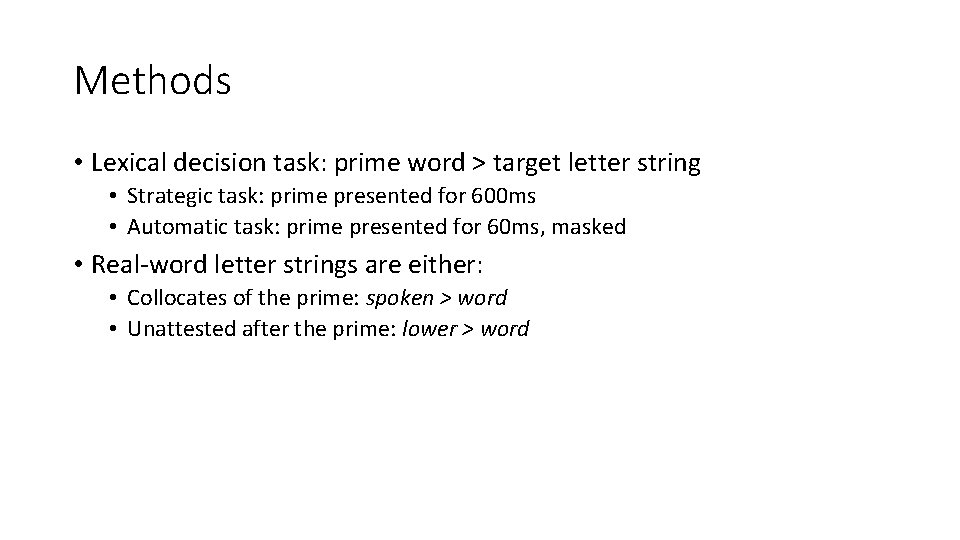

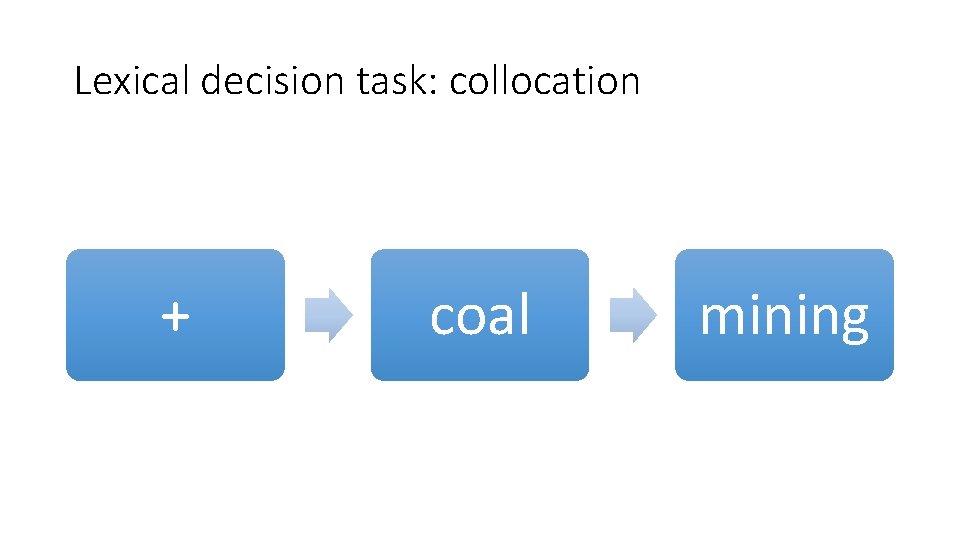

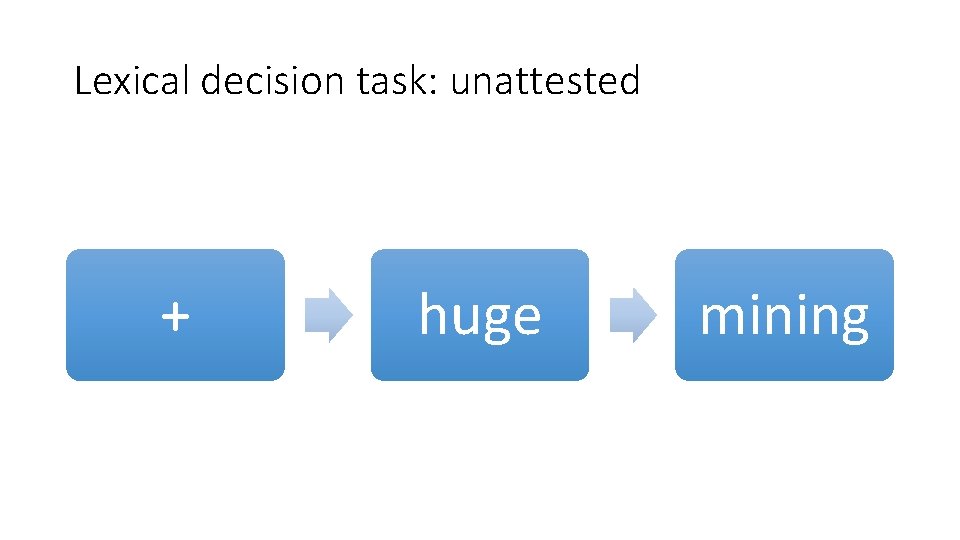

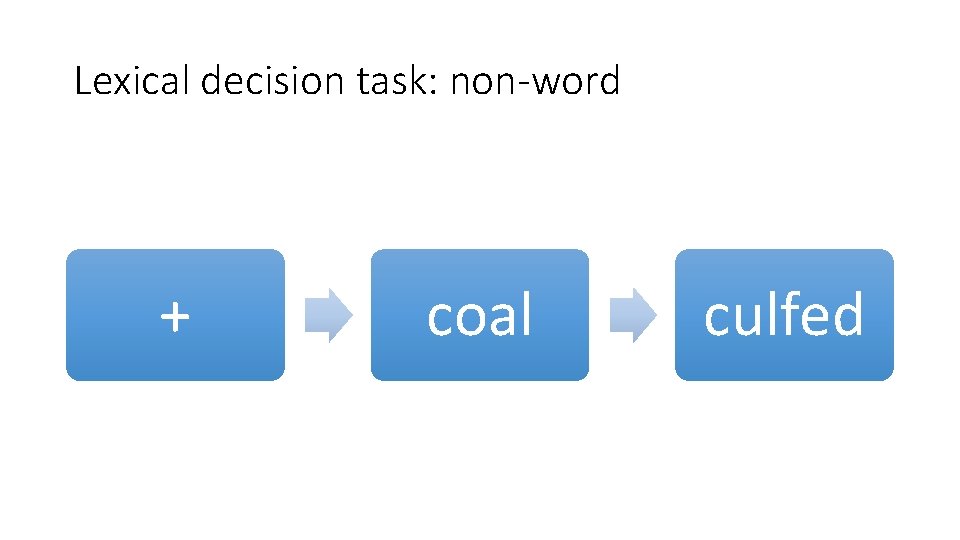

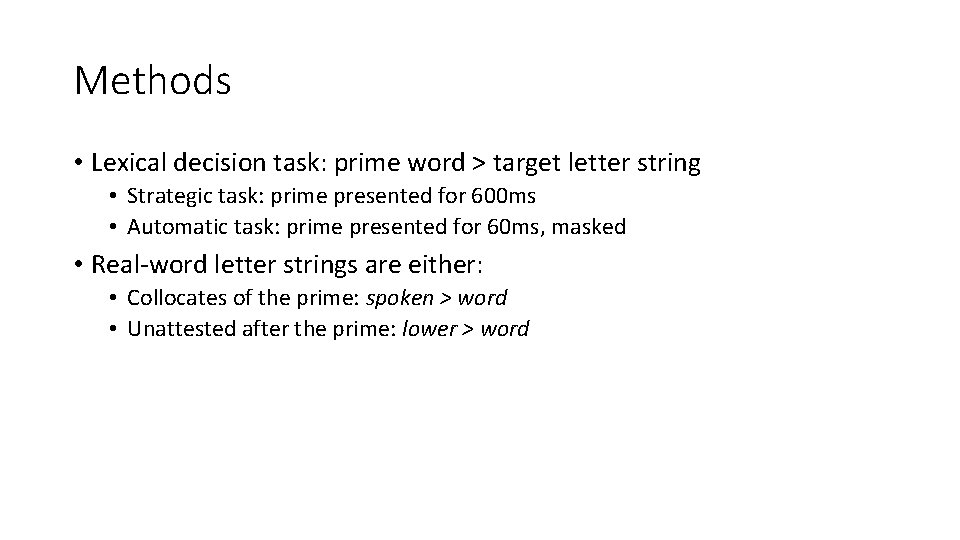

Methods • Lexical decision task: prime word > target letter string • Strategic task: prime presented for 600 ms • Automatic task: prime presented for 60 ms, masked • Real-word letter strings are either: • Collocates of the prime: spoken > word • Unattested after the prime: lower > word

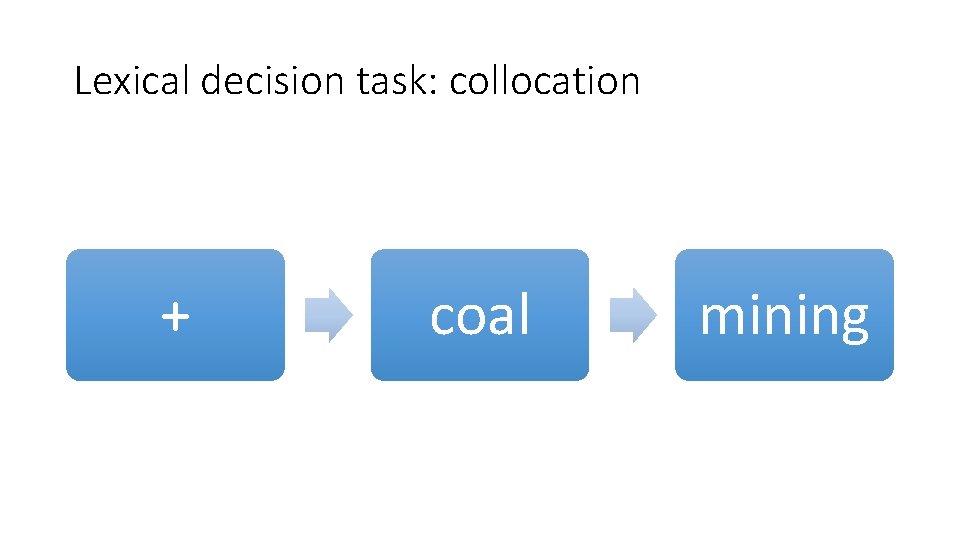

Lexical decision task: collocation + coal mining

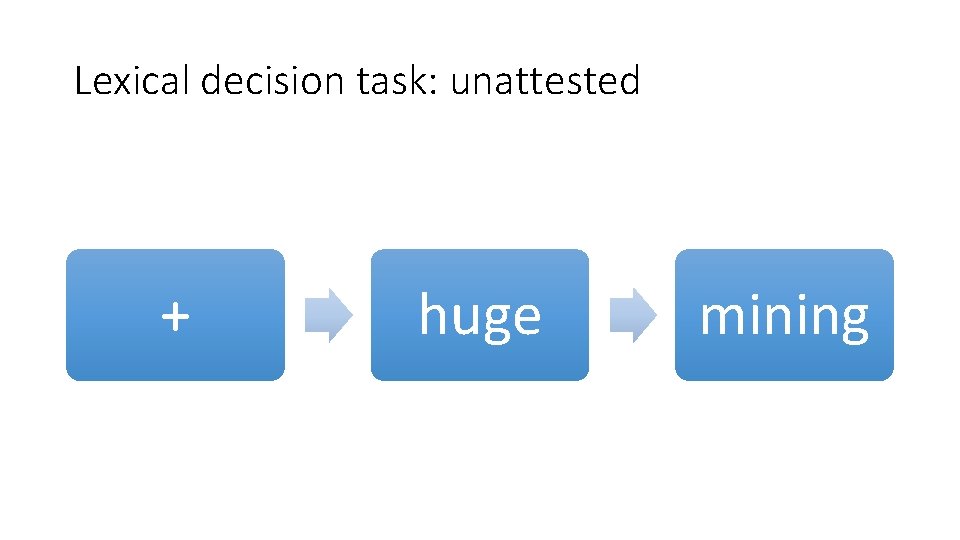

Lexical decision task: unattested + huge mining

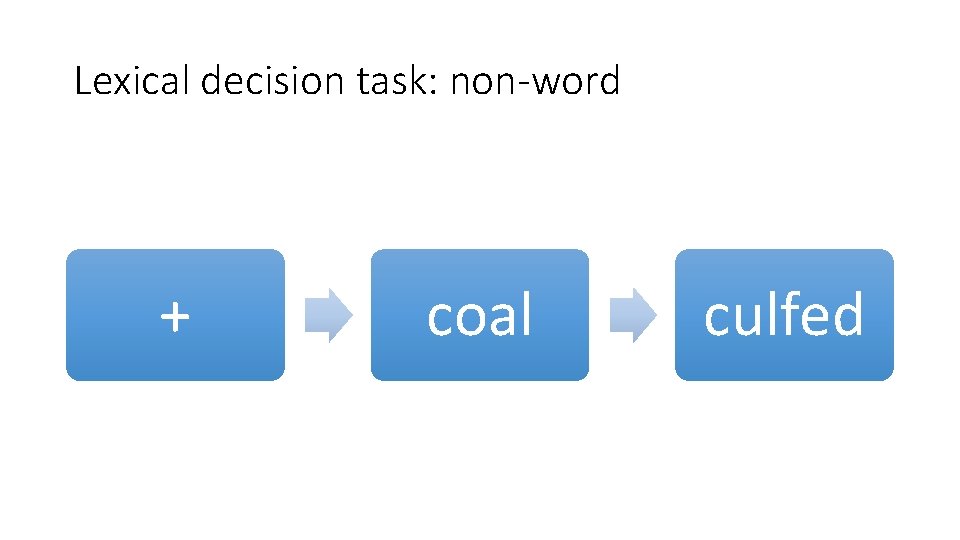

Lexical decision task: non-word + coal culfed

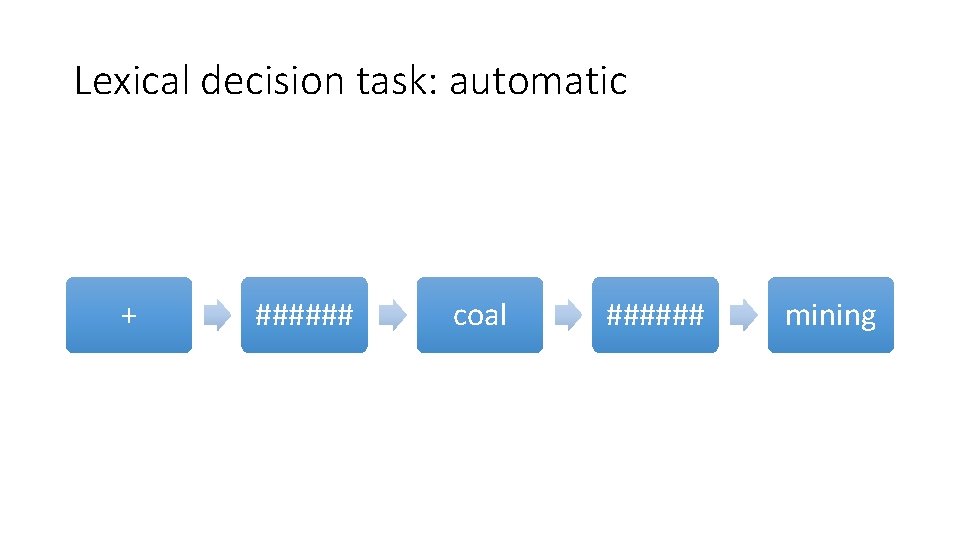

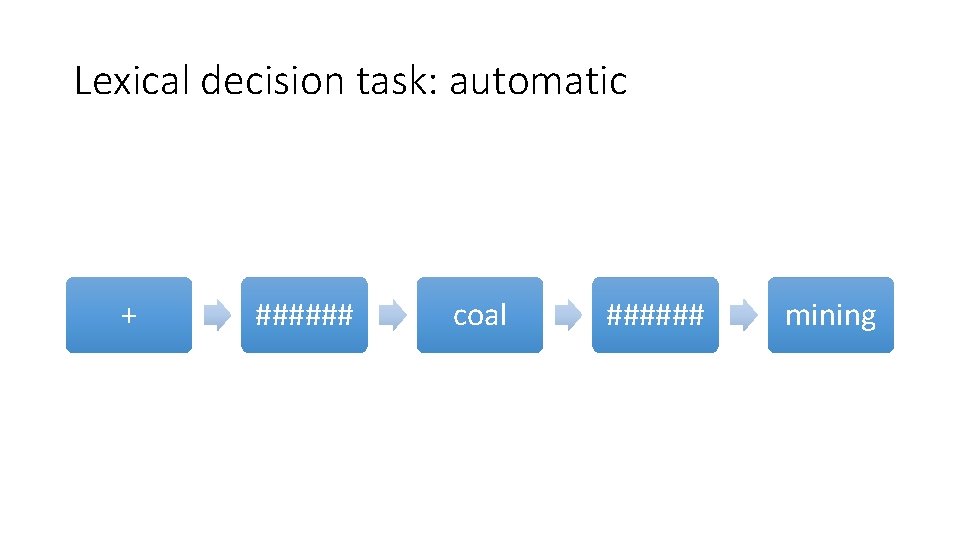

Lexical decision task: automatic + ###### coal ###### mining

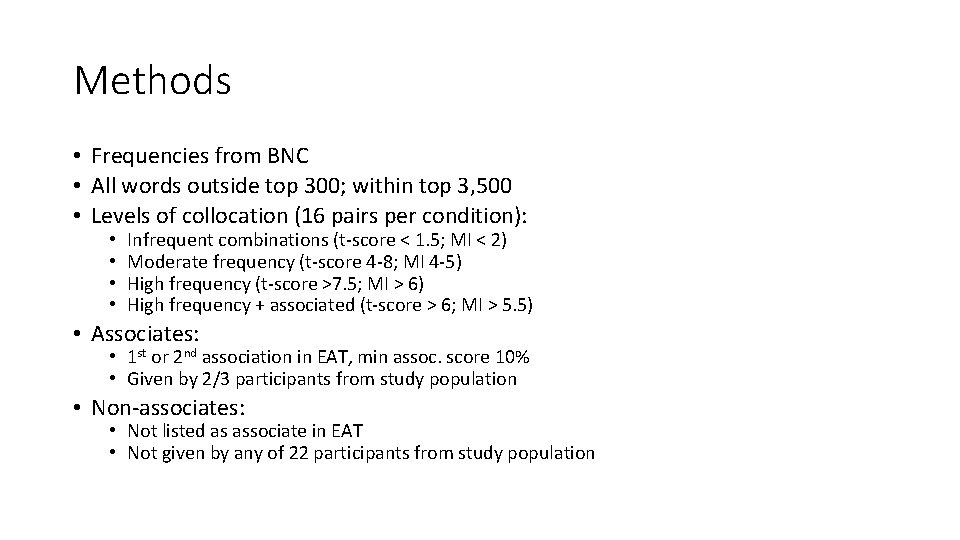

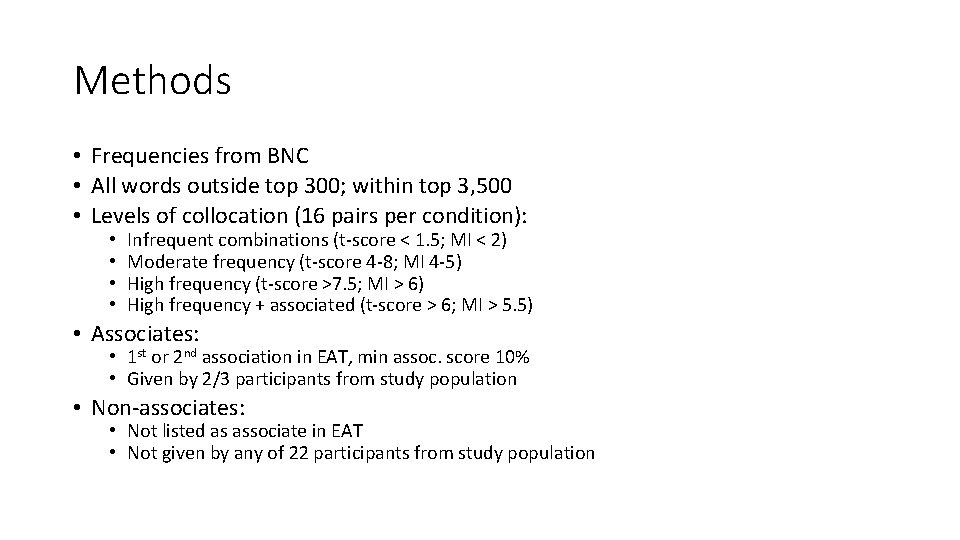

Methods • Frequencies from BNC • All words outside top 300; within top 3, 500 • Levels of collocation (16 pairs per condition): • • Infrequent combinations (t-score < 1. 5; MI < 2) Moderate frequency (t-score 4 -8; MI 4 -5) High frequency (t-score >7. 5; MI > 6) High frequency + associated (t-score > 6; MI > 5. 5) • Associates: • 1 st or 2 nd association in EAT, min assoc. score 10% • Given by 2/3 participants from study population • Non-associates: • Not listed as associate in EAT • Not given by any of 22 participants from study population

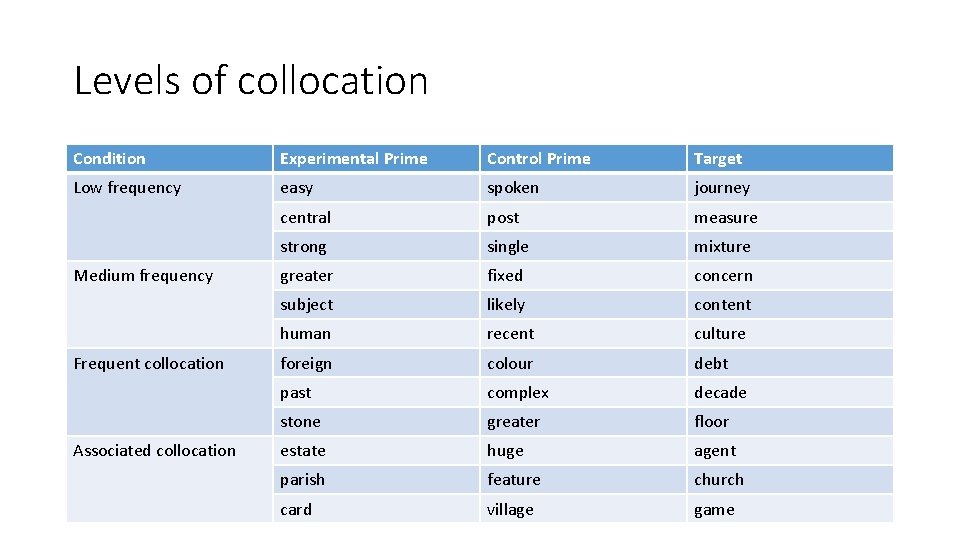

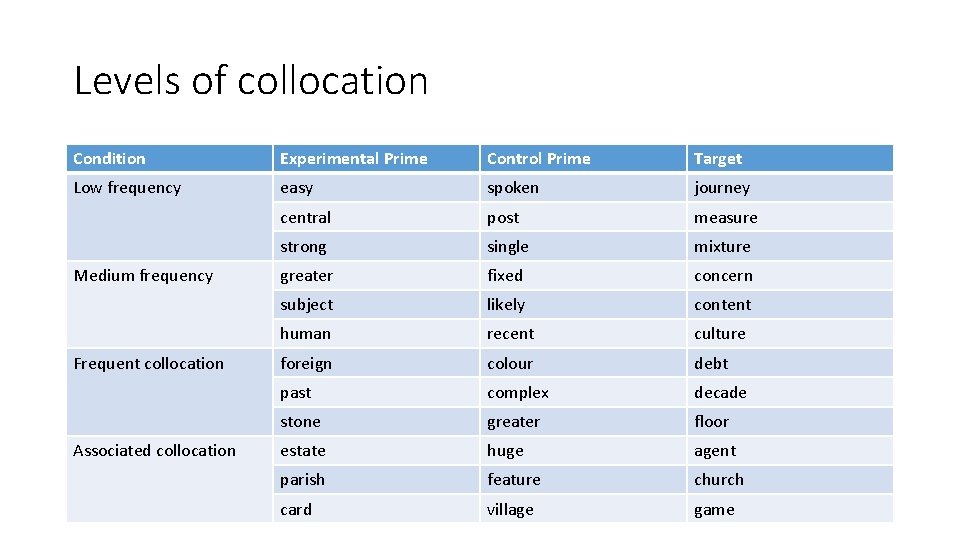

Levels of collocation Condition Experimental Prime Control Prime Target Low frequency easy spoken journey central post measure strong single mixture greater fixed concern subject likely content human recent culture foreign colour debt past complex decade stone greater floor estate huge agent parish feature church card village game Medium frequency Frequent collocation Associated collocation

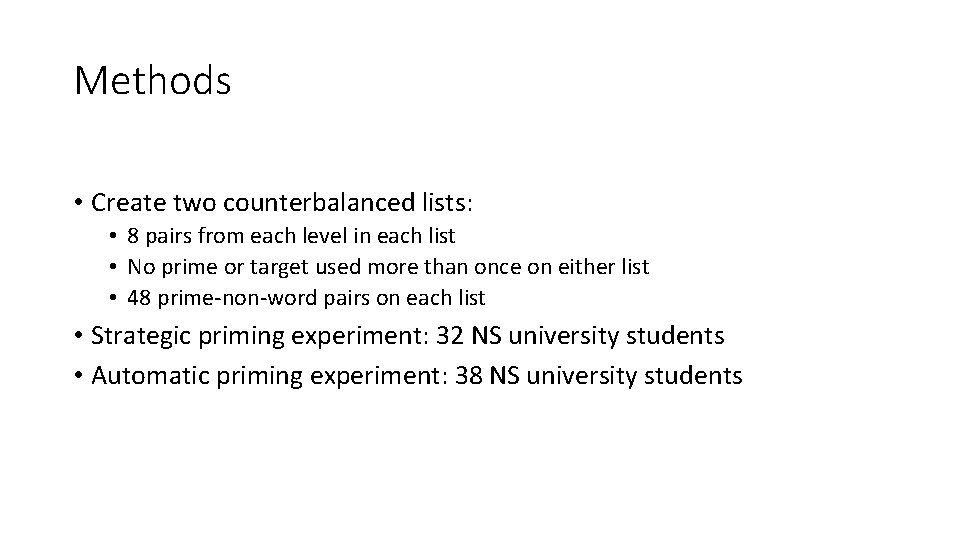

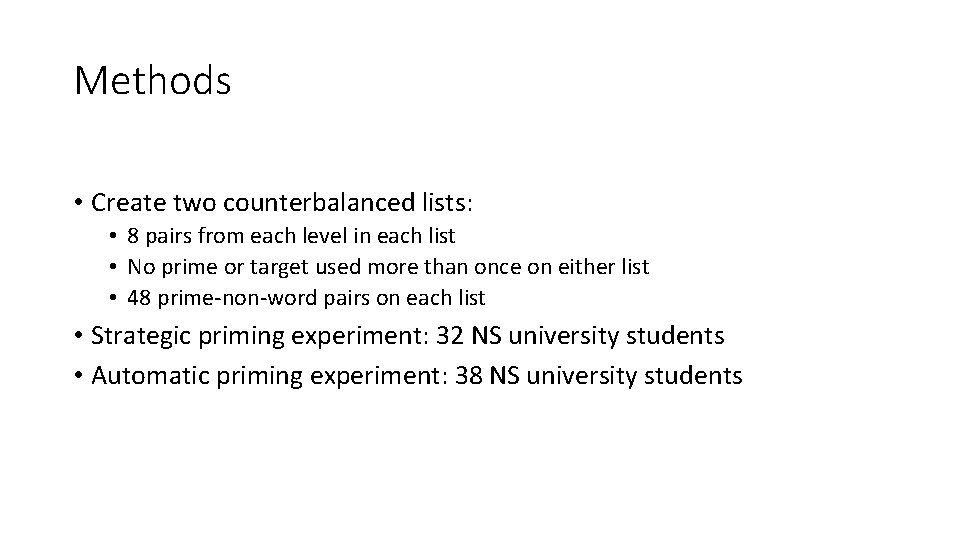

Methods • Create two counterbalanced lists: • 8 pairs from each level in each list • No prime or target used more than once on either list • 48 prime-non-word pairs on each list • Strategic priming experiment: 32 NS university students • Automatic priming experiment: 38 NS university students

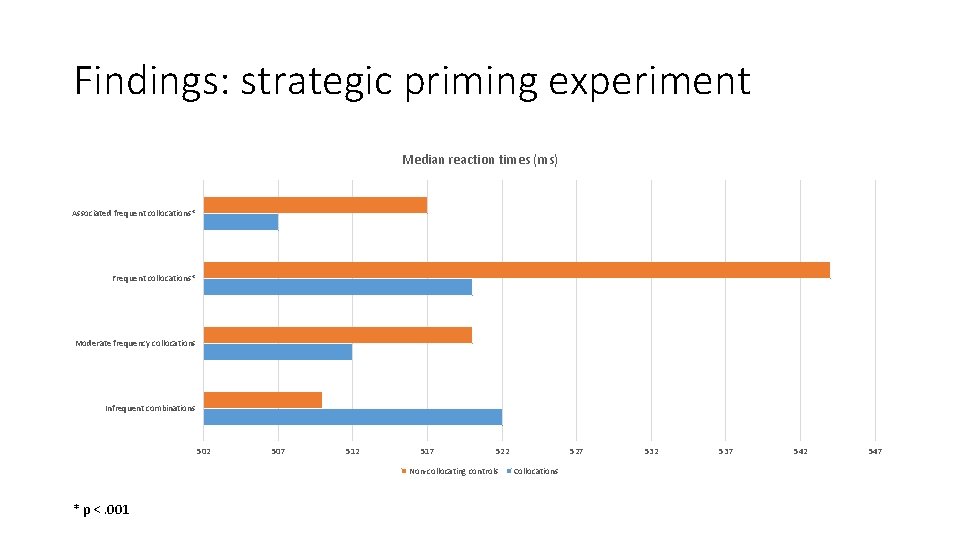

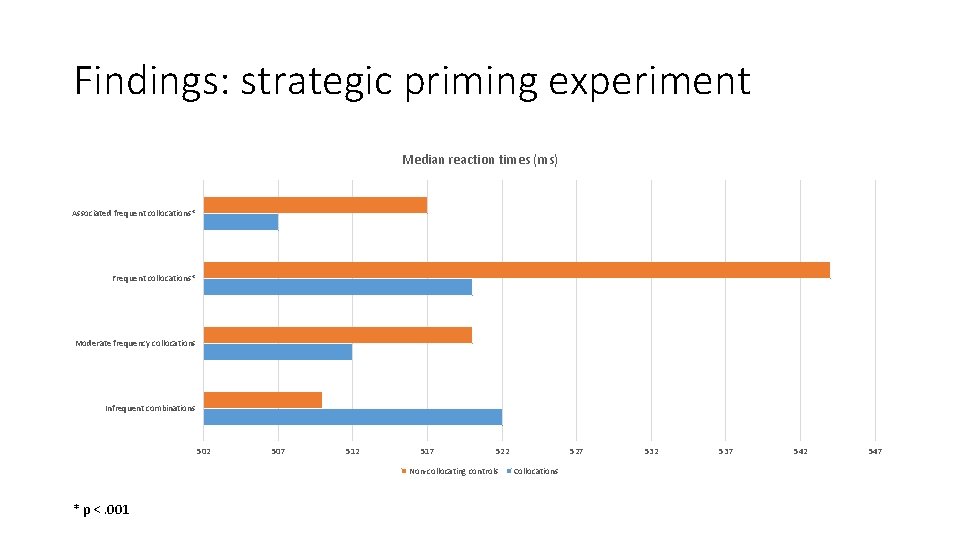

Findings: strategic priming experiment Median reaction times (ms) Associated frequent collocations* Frequent collocations* Moderate frequency collocations Infrequent combinations 502 507 512 517 522 Non-collocating controls * p <. 001 527 Collocations 532 537 542 547

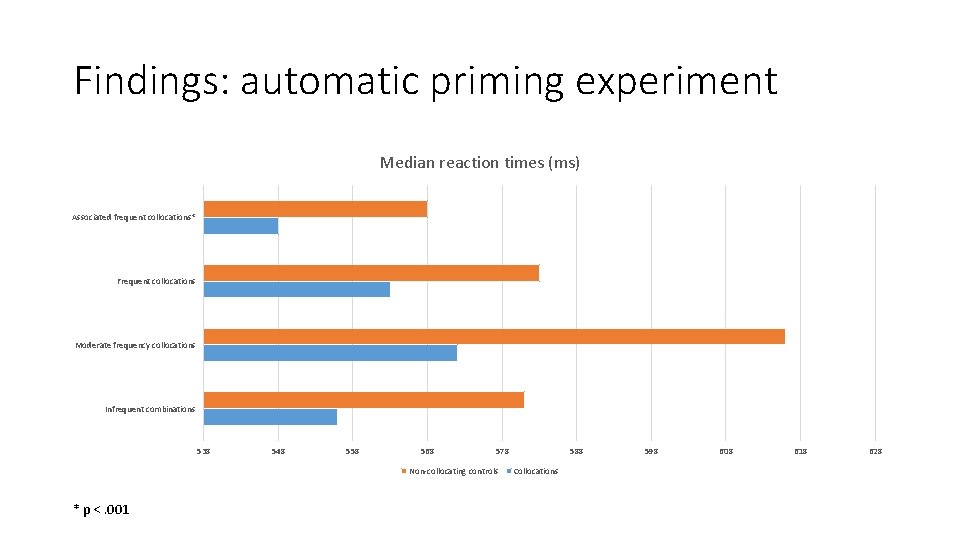

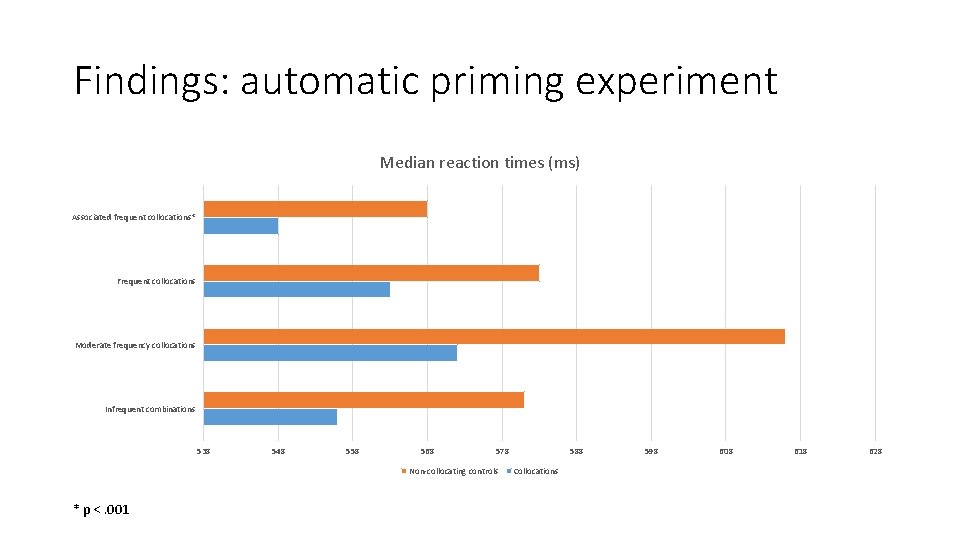

Findings: automatic priming experiment Median reaction times (ms) Associated frequent collocations* Frequent collocations Moderate frequency collocations Infrequent combinations 538 548 558 568 578 Non-collocating controls * p <. 001 588 Collocations 598 608 618 628

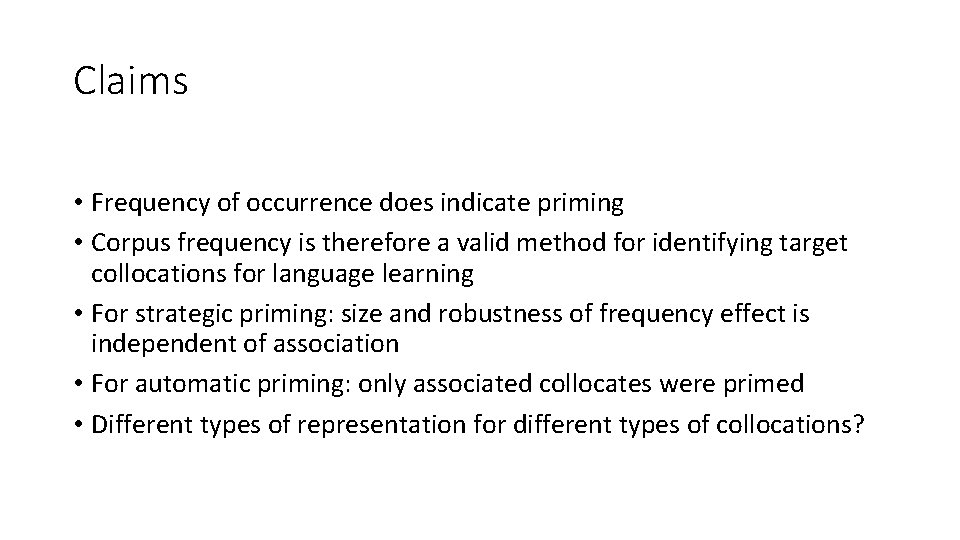

Claims • Frequency of occurrence does indicate priming • Corpus frequency is therefore a valid method for identifying target collocations for language learning • For strategic priming: size and robustness of frequency effect is independent of association • For automatic priming: only associated collocates were primed • Different types of representation for different types of collocations?

Methodological issues

Grouping collocations into frequency bands • Binary classification of predictor variables • Collocations as gradient, rather than binary

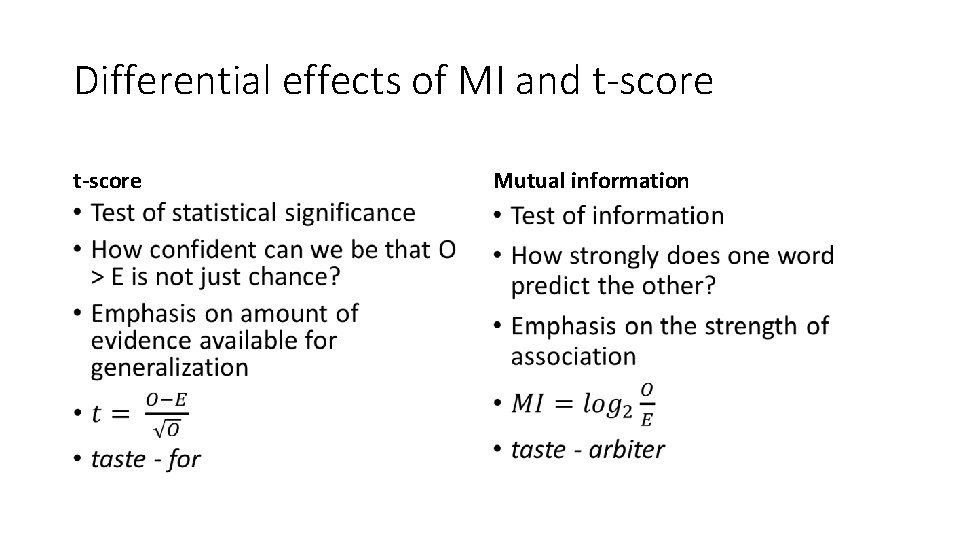

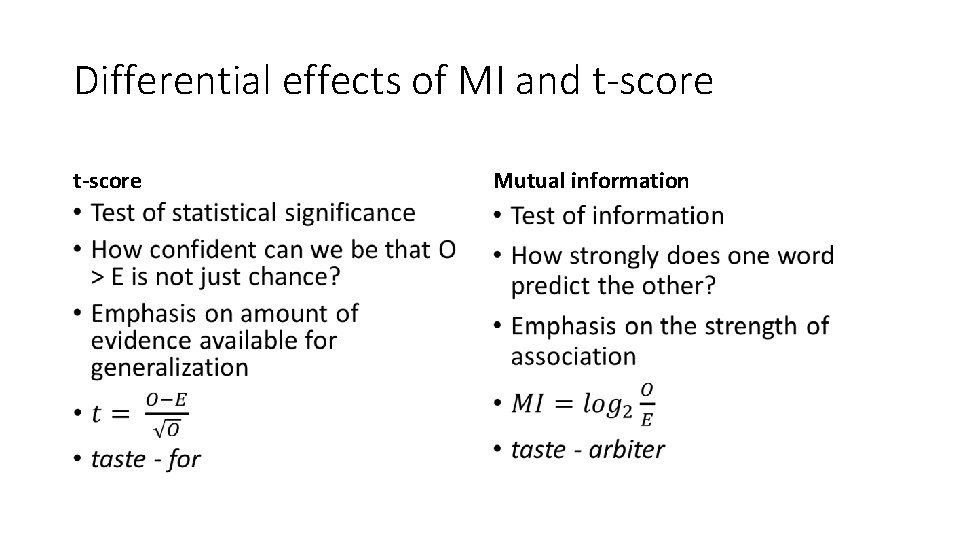

Conflating MI and t-score • MI and t-score used in combination to classify combinations • • Infrequent combinations (t-score < 1. 5; MI < 2) Moderate frequency (t-score 4 -8; MI 4 -5) High frequency (t-score >7. 5; MI > 6) High frequency + associated (t-score > 6; MI > 5. 5) • But there is evidence that their effects are likely to be different…

Logic of association measures • Is occurrence greater than chance? • i. e. is observed occurrence greater than expected occurrence?

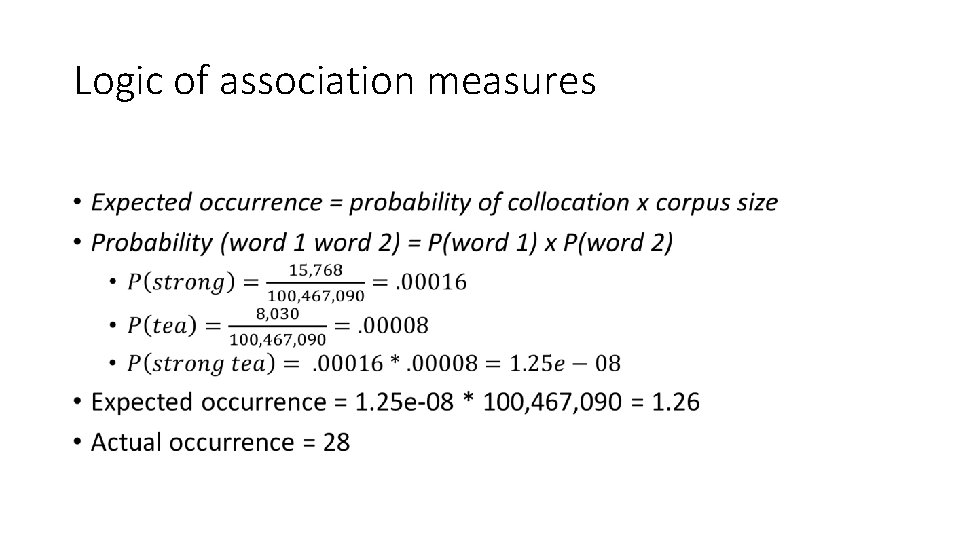

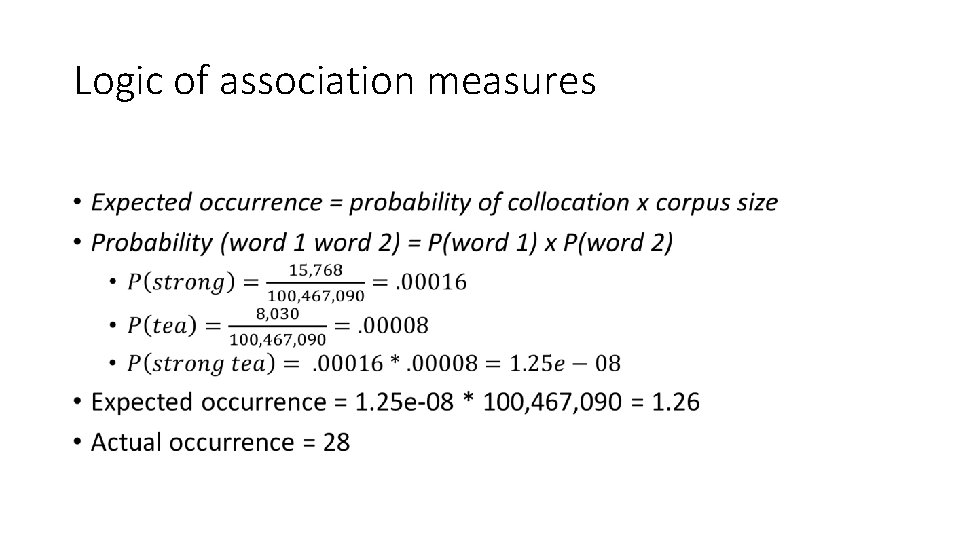

Logic of association measures •

Differential effects of MI and t-score Mutual information • •

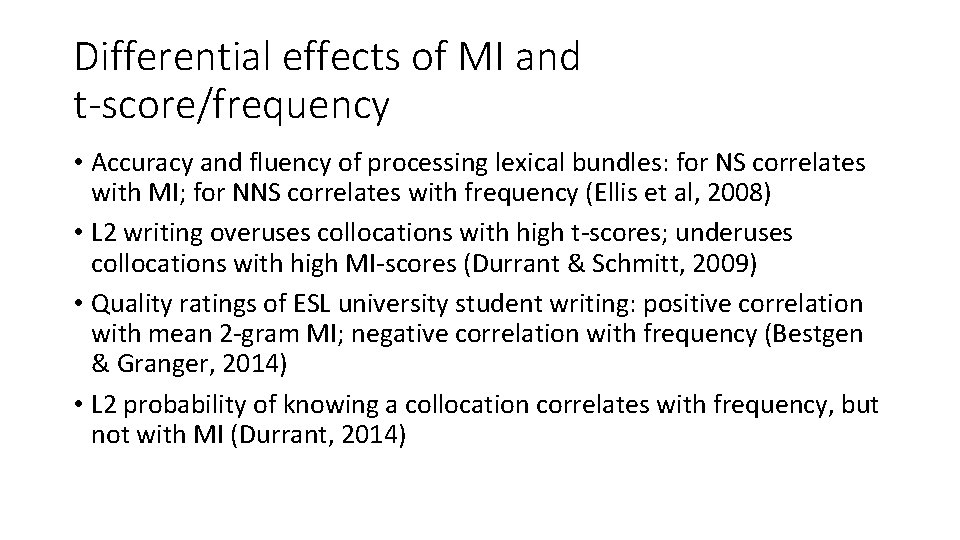

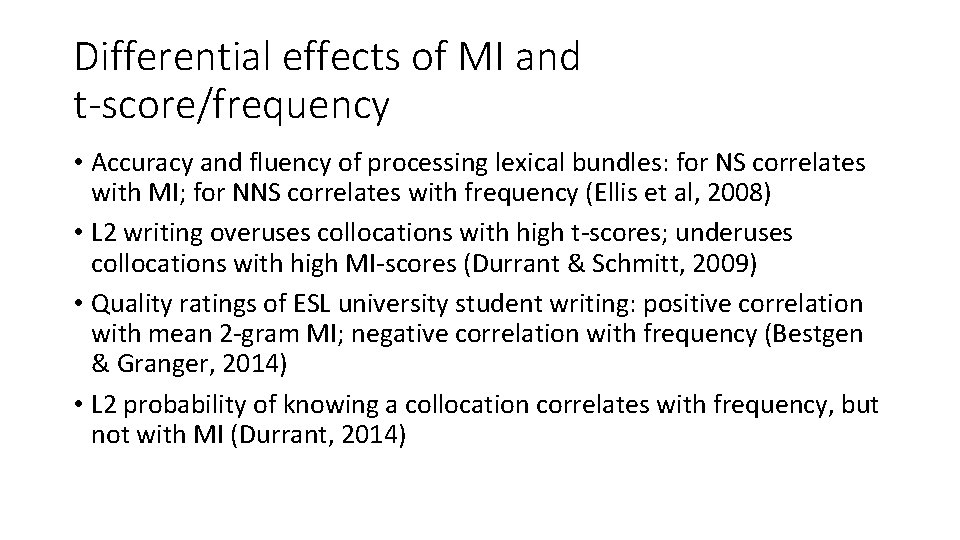

Differential effects of MI and t-score/frequency • Accuracy and fluency of processing lexical bundles: for NS correlates with MI; for NNS correlates with frequency (Ellis et al, 2008) • L 2 writing overuses collocations with high t-scores; underuses collocations with high MI-scores (Durrant & Schmitt, 2009) • Quality ratings of ESL university student writing: positive correlation with mean 2 -gram MI; negative correlation with frequency (Bestgen & Granger, 2014) • L 2 probability of knowing a collocation correlates with frequency, but not with MI (Durrant, 2014)

Theoretical issues

Theoretical issues • Arguments against frequency-based approaches to collocation • Relevance of priming for pedagogy • Modelling collocation processing • ‘Collocation’ as a non-unified phenomenon • How can psycholinguistic research and corpus research interact?

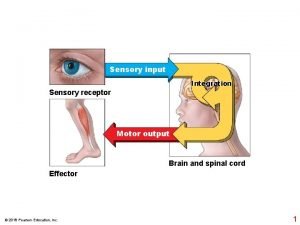

Arguments against frequency • Herbst (1996): collocation frequency simply reflects extra-linguistic facts about the world. Dark night is a frequent collocation “because nights tend to be dark and not bright” (p. 384). • Newmeyer (2003): frequency-based analysis “is no more defensible as an approach to language and the mind than would be a theory of vision that tries to tell us what we are likely to look at” (p. 697).

![The shift to color vision in primates may be related to changes in the [The shift to color vision in primates] may be related to changes in the](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/1fd4306995ae44f24a375b874417ebaa/image-38.jpg)

[The shift to color vision in primates] may be related to changes in the flora of the earth millions of years ago. It helps to think what color vision was likely good for when it first appeared. Monkeys that live in trees would benefit because color vision enabled them to discriminate many kinds of fruits and leaves and select the most nutritious among them. From studying the other primates that have color vision, we can estimate that our kind of color vision arose about 55 million years ago. At this time we find fossil evidence of changes in the composition of ancient forests. Before this time, the forests were rich in figs and palms, which are tasty but all the same general color. Later forests had more of a diversity of plants, likely with different colors. It seems a good bet that the switch to color vision correlates with a switch from a monochromatic forest to one with a richer palette of colors in food. Shubin, 2008: loc. 1873

The relevance of priming for pedagogy • “Establishing whether the high frequency collocations found in a corpus are psychologically real … has clear practical implications” • We want to identify which collocations learners should target. • So we need to know which collocations competent speakers know. • Priming can show if these items are identified from corpus data Durrant & Doherty 2010: 127

Modelling collocation processing • Collocation vs. other types of formulaic language • ‘Holistic storage’/’chunking’? • Collocation knowledge as aspect of word knowledge vs. independent construct • Different models for different language users? • L 1/L 2 (Yamashita & Jiang, 2010; Durrant, 2014) • Analytic vs. Gestalt learners (Peters, 1977; Nelson, 1981; Van Lancker-Sidtis, 2004) • Language community (Wray & Grace, 2007)

Collocation as a non-unified phenomenon • Strong vs. weak psychological associates • High-frequency collocations vs. strongly associated collocations • Fixed vs. flexible collocations • ‘Literal’ vs. semantically-specialised collocations • L 1 -congruent vs. non-congruent collocations

Conclusions • Position of Hoey (2005) and Durrant & Doherty (2010) in framework of corpus-psycholinguistic integration • Some key arguments about the relevance of corpus and psycholinguistic data no longer ring true to me • Durrant & Doherty (2010) shows priming paradigm detects differences between collocations and non-collocations and between associated/non-associated collocations, but… • Binary nature of paradigm is not ideal • Different types of psycholinguistic model may be needed for different categories of language users/collocations/formulas.

References • Bestgen, Y. , & Granger, S. (2014). Quantifying the development of phraseological competence in L 2 English writing: An automated approach. Journal of second language writing, 26, 28 -41. • Durrant, P. (2014). Corpus frequency and second language learners' knowledge of collocations. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics, 19(4), 443 -477. • Durrant, P. , & Doherty, A. (2010). Are high-frequency collocations psychologically real? Investigating thesis of collocational priming. Corpus linguistics and linguistic theory, 6(2), 125 -155. • Durrant, P. , & Schmitt, N. (2009). To what extent do native and non-native writers make use of collocations? International review of applied linguistics, 47(2), 157 -177. • Ellis, N. C. , Simpson-Vlach, R. , & Maynard, C. (2008). Formulaic language in native and second-language speakers: psycholinguistics, corpus linguistics, and TESOL Quarterly, 41(3), 375 -396.

References • Herbst, T. (1996). What are collocations: sandy beaches or false teeth? English studies, 4, 379 -393. • Hoey, M. (2005). Lexical priming: A new theory of words and language. London: Routledge. • Lamb, S. (2000). Bidirectional processing in language and related cognitive systems. In M. Barlow & S. Kemmer (Eds. ), Usage based models of language (pp. 87 -119). Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications. • Meyer, J. , & Land, R. (2003). Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge: Linkages to Ways of Thinking and Practising within the Disciplines. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh. • Nelson, K. (1981). Individual differences in language development: implications for development and language. Developmental Psychology, 17(2), 170 -187. • Newmeyer, F. (2003). Grammar is grammar and usage is usage. Language, 79, 682 -707.

References • Peters, A. M. (1977). Language-learning strategies: does the whole equal the sum of the parts? Language, 53(3), 560 -573. • Sinclair, J. M. Collocation: A progress report. In R. Steel, & T. Threadgold (Eds. ), Language topics: Essays in honour of Michael Halliday (Vol. 2, pp. 319 -331). Amsterdam: John Bejamins. • Van Lancker-Sidtis, D. (2004). When novel sentences spoken or heard for the first time in the history of the universe are not enough: toward a dual-process model of language. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 39(1), 1 -44. • Wray, A. , & Grace, G. W. (2007). The consequences of talking to strangers: Evolutionary corollaries of socio-cultural influences on linguistic form. Lingua, 117, 543 -578. • Yamashita, J. , & Jiang, N. (2010). L 1 influence on the acquisition of L 2 collocations: Japanese ESL users and EFL learners acquiring English collocations. TESOL Quarterly, 44(4), 647 -668.

Oogenesis

Oogenesis Petek korkusuz

Petek korkusuz Bakit ang pagbasa ay isang psycholinguistic guessing game

Bakit ang pagbasa ay isang psycholinguistic guessing game Psycholinguistics aspects of interlanguage

Psycholinguistics aspects of interlanguage Psycholinguistic aspects of interlanguage

Psycholinguistic aspects of interlanguage Psycholinguistic aspects of interlanguage

Psycholinguistic aspects of interlanguage Psycholinguistic guessing game

Psycholinguistic guessing game Psycholinguistic aspects of interlanguage

Psycholinguistic aspects of interlanguage Priming memory examples

Priming memory examples Priming memory

Priming memory Priming the hplc system

Priming the hplc system Priming memory

Priming memory Context dependent memory ap psychology

Context dependent memory ap psychology Rpg test

Rpg test Conceptual priming

Conceptual priming Zoom lens model of attention

Zoom lens model of attention Chunking ap psychology examples

Chunking ap psychology examples Conceptual priming

Conceptual priming Constanze vorwerg

Constanze vorwerg Contoh pemrosesan otomatis

Contoh pemrosesan otomatis Ecmo weaning criteria

Ecmo weaning criteria Priming

Priming Integrating classification and association rule mining

Integrating classification and association rule mining Exemplifies the complexity of relationships

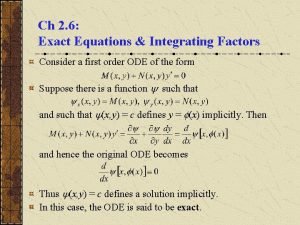

Exemplifies the complexity of relationships Exact equations and integrating factors

Exact equations and integrating factors Integrating science and social studies

Integrating science and social studies Chapter 4 strategic management

Chapter 4 strategic management Integrating qualitative and quantitative methods

Integrating qualitative and quantitative methods Tactical communication skills

Tactical communication skills Integrating sel and pbis

Integrating sel and pbis Integrating public health and primary care

Integrating public health and primary care Signal phrases

Signal phrases Embedded quotes mla examples

Embedded quotes mla examples Pellucidum

Pellucidum Differential equation exponential solution

Differential equation exponential solution Integrating plm system in dynamics

Integrating plm system in dynamics Basic concepts on integrating technology in instruction

Basic concepts on integrating technology in instruction Integrating factor formula

Integrating factor formula Integrating marketing communication to build brand equity

Integrating marketing communication to build brand equity Conscious marketing vs csr

Conscious marketing vs csr Integrating type dvm

Integrating type dvm Integration by parts meaning

Integration by parts meaning Differentiating stage of a relationship

Differentiating stage of a relationship Integrating factor of differential equation

Integrating factor of differential equation Dialogue quote vs flow quote

Dialogue quote vs flow quote Integrating factor of differential equation

Integrating factor of differential equation