Recommendations Adoption Leave for Adoptive Parents Commissioning Parent

- Slides: 20

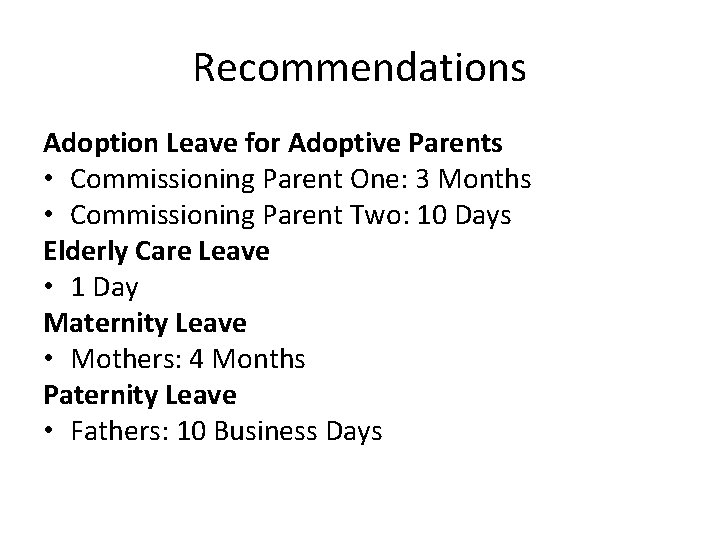

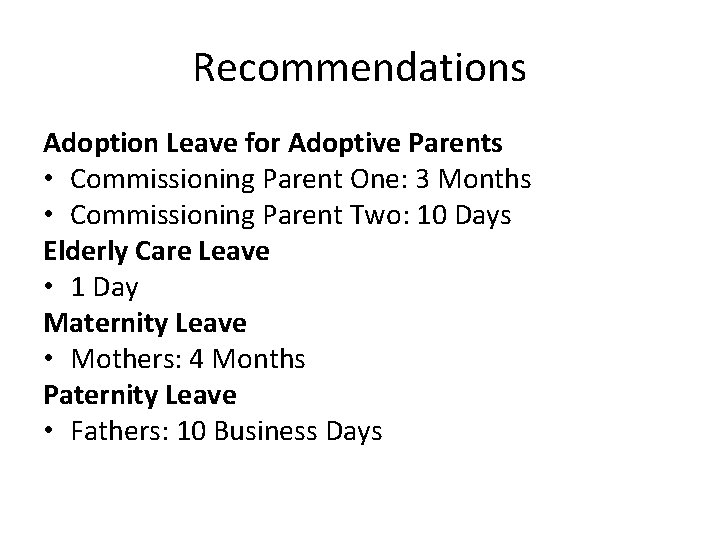

Recommendations Adoption Leave for Adoptive Parents • Commissioning Parent One: 3 Months • Commissioning Parent Two: 10 Days Elderly Care Leave • 1 Day Maternity Leave • Mothers: 4 Months Paternity Leave • Fathers: 10 Business Days

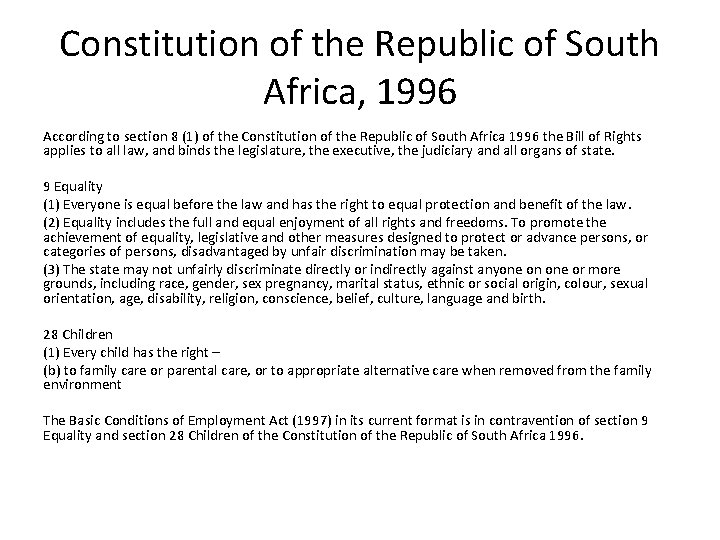

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 According to section 8 (1) of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 1996 the Bill of Rights applies to all law, and binds the legislature, the executive, the judiciary and all organs of state. 9 Equality (1) Everyone is equal before the law and has the right to equal protection and benefit of the law. (2) Equality includes the full and equal enjoyment of all rights and freedoms. To promote the achievement of equality, legislative and other measures designed to protect or advance persons, or categories of persons, disadvantaged by unfair discrimination may be taken. (3) The state may not unfairly discriminate directly or indirectly against anyone on one or more grounds, including race, gender, sex pregnancy, marital status, ethnic or social origin, colour, sexual orientation, age, disability, religion, conscience, belief, culture, language and birth. 28 Children (1) Every child has the right – (b) to family care or parental care, or to appropriate alternative care when removed from the family environment The Basic Conditions of Employment Act (1997) in its current format is in contravention of section 9 Equality and section 28 Children of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa 1996.

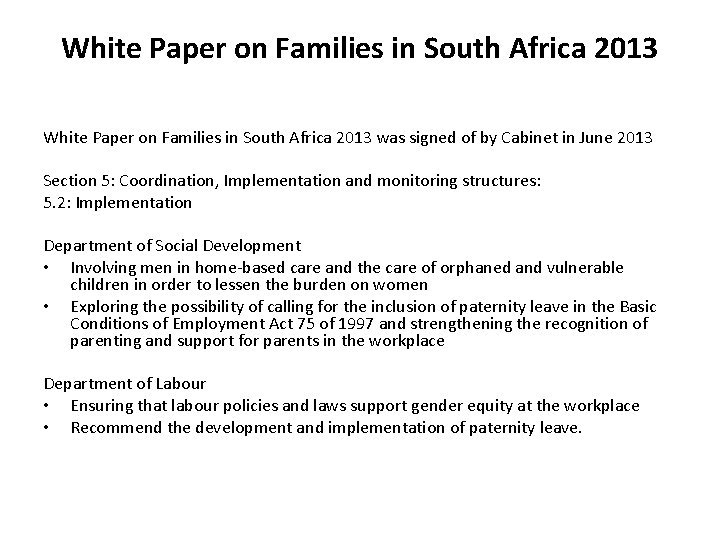

White Paper on Families in South Africa 2013 was signed of by Cabinet in June 2013 Section 5: Coordination, Implementation and monitoring structures: 5. 2: Implementation Department of Social Development • Involving men in home-based care and the care of orphaned and vulnerable children in order to lessen the burden on women • Exploring the possibility of calling for the inclusion of paternity leave in the Basic Conditions of Employment Act 75 of 1997 and strengthening the recognition of parenting and support for parents in the workplace Department of Labour • Ensuring that labour policies and laws support gender equity at the workplace • Recommend the development and implementation of paternity leave.

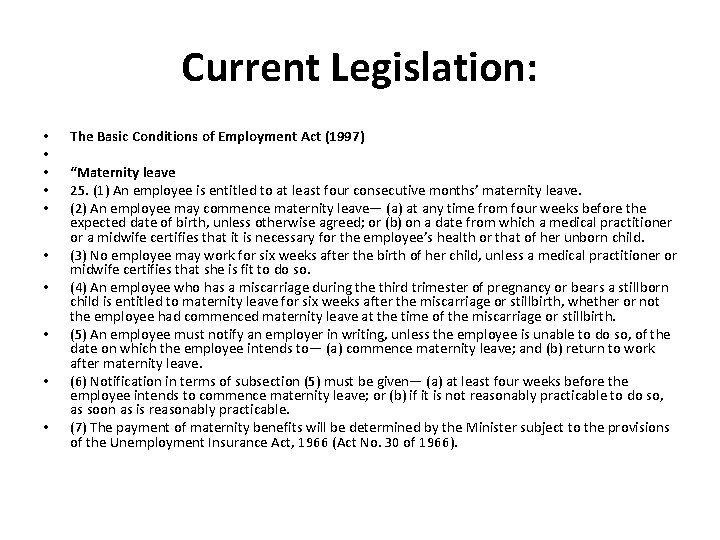

Current Legislation: • • • The Basic Conditions of Employment Act (1997) “Maternity leave 25. (1) An employee is entitled to at least four consecutive months’ maternity leave. (2) An employee may commence maternity leave— (a) at any time from four weeks before the expected date of birth, unless otherwise agreed; or (b) on a date from which a medical practitioner or a midwife certifies that it is necessary for the employee’s health or that of her unborn child. (3) No employee may work for six weeks after the birth of her child, unless a medical practitioner or midwife certifies that she is fit to do so. (4) An employee who has a miscarriage during the third trimester of pregnancy or bears a stillborn child is entitled to maternity leave for six weeks after the miscarriage or stillbirth, whether or not the employee had commenced maternity leave at the time of the miscarriage or stillbirth. (5) An employee must notify an employer in writing, unless the employee is unable to do so, of the date on which the employee intends to— (a) commence maternity leave; and (b) return to work after maternity leave. (6) Notification in terms of subsection (5) must be given— (a) at least four weeks before the employee intends to commence maternity leave; or (b) if it is not reasonably practicable to do so, as soon as is reasonably practicable. (7) The payment of maternity benefits will be determined by the Minister subject to the provisions of the Unemployment Insurance Act, 1966 (Act No. 30 of 1966).

Current Legislation: The Basic Conditions of Employment Act (1997) “Family responsibility leave 27. (1) This section applies to an employee— (a) who has been in employment with an employer for longer than four months; and (b) who works for at least four days a week for that employer. (2) An employer must grant an employee, during each annual leave cycle, at the request of the employee, three days’ paid leave, which the employee is entitled to take— (a) when the employee’s child is born; (b) when the employee’s child is sick; or (c) in the event of the death of— (i) the employee’s spouse or life partner; or (ii) the employee’s parent, adoptive parent, grandparent, child, adopted child, grandchild or sibling.

(3) Subject to subsection (5), an employer must pay an employee for a day’s family responsibility leave— (a) the wage the employee would ordinarily have received for work on that day; and (b) on the employee’s usual pay day. (4)An employee may take family responsibility leave in respect of the whole or a part of a day. (5) Before paying an employee for leave in terms of this section, an employer may require reasonable proof of an event contemplated in subsection (1) for which the leave was required. (6) An employee’s unused entitlement to leave in terms of this section lapses at the end of the annual leave cycle in which it accrues. (7)Acollective agreement may vary the number of days and the circumstances under which leave is to be granted in terms of this section. ”

Cost of Ten Days Paid Paternity Leave • The only negative aspect of 10 Days Paid Paternity Leave is the actual cost to the employer with the Ten Days absenteeism of Fathers with the birth of their child (ren) from work. • The average monthly income for employed males aged 15 -64, as per Census 2011 was R 9 396 per month. If the average salary per month was R 9 396. 00 than the cost of Paternity Leave for 10 Days will be +/- R 4 335. 95 per birth of a child. • The Unemployment Insurance Fund Act 2001 can be amended to include Right to Paternity Benefits • Total Fertility Rate: average number of children born to a woman during her lifetime South Africa 2. 3 World 2. 5 (Population Reference Burea)

Impact / Benefit of Paternity Leave: Impact on Children: • In the UK, fathers’ not using paternity leave or not sharing childcare responsibilities are associated with increased likelihood of their three year old having developmental problems (Dex & Ward, 2007) • In Sweden an increase in fathers’ share of parental leave over time has been paralleled by a downward trend in child injury rates, age 0 -4 years (Laflamme et al, 2012) • Some have suggested that leave-taking by fathers would be associated with greater incidence of child injury. This is not born out in the research: in Sweden, child injury (age 0 -2 years) was lower during paternity as compared with maternity leave (Laflamme et al, 2012) • If one parent is better-educated than the other, some children may benefit from the better-educated parent undertaking more care: e. g. in Norway, girls (but not boys) have been found to do better at school when a father who was better educated than their mother took longer-than-average leave (Cools et al, 2011. ) In Sweden, longer leave-taking by mothers only impacted positively on children’s scholastic performance if the mother was highly educated (Liu and Sans, 2010). • Australian children whose fathers take long leave after their birth perform better in cognitive development tests and are more likely to be prepared for school at ages four and five (Huerta et al, 2013) • High take up of parental leave by Swedish fathers is linked to more contact with children after separation (Duvander and Jans, 2009).

Impact on Mothers: • In the UK, a father’s taking paternity leave is strongly associated with mothers’ well-being three months after the birth (Redshaw & Henderson, 2013) • In Norway, mothers’ absence due to sickness is reduced by about 5– 10% from an average level of 20% in families where fathers take longer leave (Bratberg and Naz, 2009) • In France, when paternity leave results in more infant care by fathers, new mothers are less likely to be depressed (Séjourné et al, 2012)

Impact on couples: • In Norway, following the introduction of the four-week ‘daddy quota’ significant numbers of fathers took longer leave. After this, an 11% lower level of conflict over household division of labour was found, and couples were 50% more likely to share clothes-washing equally (Kotsadam and Finseraas, 2011). • Similarly, in Quebec, some years after the introduction of their ‘daddy quota’, fathers were found to be more engaged in routine household tasks (Patnaik, 2013 ). A robust evidence base finds that greater participation in household chores is connected with couple relationship stability. • Swedish couples are 30% less likely to separate if the father took more than two weeks leave to care for their first child (Olah, 2001). • There is less violence in families where fathers have taken parental leave (Holter et al, 2008)

Impact on Fathers: • Swedish fathers who took paternity leave in the late 1970 s have had an 18% lower risk of alcohol-related care and/or death than other fathers and a 16% overall reduced risk of early death (Mansdotter et al, 2008; Mansdotter et al, 2007). • Swedish fathers who take longer leave are more satisfied with time spent with their children (Haas & Hwang, 2008). • Israeli and US fathers who take longer leave remain more focused on their infant afterwards and more supportive to their partner, and place higher value on family life. Employer responses to their leave-taking are also more positive (Feldman et al, 2004).

The impact of longer leave-taking on fathers’ childcare involvement • Swedish fathers who took 120 or more days of leave during the 1990 s reported that taking this leave enabled them to develop closer emotional relationships with their children and this made them feel responsible for childcare after the leave period was over (Chronholm, 2004) • In Norway, two early in-depth studies of ‘leave sharing couples’ found that when fathers take leave ‘there is a redefinition and redistribution’ of tasks at home (Brandth and Kvande, 1998) and ‘a development of competence’ in childcare (Brandth and Kvande, 2005). • More recently, taking account of fathers’ education and income, studies in the US (Nepomnyaschy and Waldfogel, 2007) and the UK (Tanaka and Waldfogel, 2007) found a significant connection between fathers’ taking leave around the birth and involvement in the care of their babies and young children later. • For example, UK fathers who take formal leave are 25% more likely to change nappies and 19% more likely to feed their 8 -12 month old babies and to get up to them at night (Tanaka and Waldfogel, 2007). This was unrelated to their commitment to parenting before the child’s birth and was irrespective of the time mothers or other family members spent with the children (Huerta et al, 2013). • Analysis of Swedish fathers working in large private companies showed that fathers who took longer leave were more involved in the care of their children right up to age 12. And any leave-taking was connected with fathers being more likely to look after children on their own while the mothers worked (Haas & Hwang, 2008). • In Australia, Hosking et al. (2010) found an association between fathers’ leave-taking and being more likely to look after children on their own at weekends (Hoskings et al, 2010); and Huerta et al (2013) reported that Australian fathers who had taken 10 or more days off work around childbirth were more likely to be involved in childcare-related activities when children were 2 to 3 years old.

Impact on couples: • In Norway, following the introduction of the four-week ‘daddy quota’ significant numbers of fathers took longer leave. After this, an 11% lower level of conflict over household division of labour was found, and couples were 50% more likely to share clothes-washing equally (Kotsadam and Finseraas, 2011). • Similarly, in Quebec, some years after the introduction of their ‘daddy quota’, fathers were found to be more engaged in routine household tasks (Patnaik, 2013 ). A robust evidence base finds that greater participation in household chores is connected with couple relationship stability. • Swedish couples are 30% less likely to separate if the father took more than two weeks leave to care for their first child (Olah, 2001). • There is less violence in families where fathers have taken parental leave (Holter et al, 2008)

The Business Case for Paternity Leave by the Fatherhood Institute Fathers’ take-up of paternity and parental leave enables mothers to take shorter maternity leave: this is helpful to employers Employers told the UK’s Department of Trade and Industry when paternity leave was first mooted, that maternity leave greater than six months was particularly problematic for them. As the length of fulltime maternity leave taken extends beyond 20 weeks (Plantenga, 2009, cited by O’Brien, 2009) or six months (Cawston et al, 2009), so do the negative effects on women’s wages and future economic wellbeing, with negative knock-on effects for employers who have ‘wasted’ resources on training and promoting women who are out of the workplace for so long – and then tend to move into lower skilled, often part time, work. The Women and Work Commission has estimated that Britain is losing £ 15 bn£ 23 bn per year due to the under-use of women’s skills (EHRC, 2009), this national financial loss translating into loss for individuals – and both large and small businesses. Paternity and Additional Paternity Leave enable fathers to become more skilled at babycare and to take on more of the caring. Research shows that many more women would be willing to return to work if their babies were being looked after by their babies’ fathers (Hand, 2005; Houston & Marks, 2005). When women take shorter maternity leave, this strengthens their attachment to the workforce and enables them to maintain or improve employment gains with knock-on positive effects for employers who are then maximising their investment in the women. Researchers in Sweden have shown that for every additional month of leave taken by a father, his partner’s annual income increases by 7% (Johansson, 2010).

Fathers’ take up of Paternity and Additional Paternity Leave may improve both fathers’ and mothers’ physical and mental health - with positive spinoffs for employers, given the costs to them of poor employee health. Reducing mothers’ sole responsibility for infants and young children through more active paternal care, and supporting mothers to interact with adults outside the child-rearing arena (for example, in employment) are likely to contribute to better mental health among mothers and reduced parenting stress (Hrdy, 2009 – pp 168 -171). Similarly, increasing the likelihood of mothers’ participating substantially in the paid workforce may improve fathers’ health and wellbeing: employed fathers with employed partners have a significantly better sense of purpose and wellbeing (Lancaster University Management School/Working Families, 2010); and employed fathers whose partners do not work are the most likely to suffer stress (Cowan & Cowan, 2000), possibly because they are totally responsible for breadwinning in their families. A correlation has recently been found between fathers’ uptake of paternity leave and their longer term health, evidenced by delayed death. Based on a population of all Swedish couples who had their first child together in 1978 (45, 801 males), the risk of death for men who took paternity leave was found to decrease by 16% (Mansdotter et al, 2007). While health-related selection is likely to be a factor, this cannot explain the whole variance; and it is thought that, among other things, taking paternity leave may set in train a diminution in traditional masculine health behaviours, which are strongly linked to poor health outcomes among men. The act of caring for babies renders fathers/men more nurturing, and is correlated with raised levels of hormones associated with tolerance/trust (oxytocin), sensitivity to infants (cortisol) and brooding/lactation/bonding (prolactin). Among males, physiological changes can occur with 15 minutes of holding a baby; and the more experienced a male is as a caregiver, the more pronounced are the changes (Hrdy, 2009 – pp 168 -171).

Addressing fathers’ caring responsibilities transparently through paternity leave enables employers to optimise the men’s performance. ‘Sweeping fatherhood under the carpet’ is no longer a viable strategy. Today’s fathers have substantial caring responsibilities. Employed fathers usually have employed partners – and UK dads with full-time employed partners do 33% of child-related tasks on weekdays and more at weekends (EOC, 2003). Where mothers work part-time, couples may ‘box and cox’ shifts. For instance, 21% of fathers of under-fives are solely responsible for childcare at some point during the working week; and 43% of fathers of school-aged children care for them alone before or after school every week (EHRC, 2009 b). Among separated fathers, 40% have responsibility for their children part of every week; and 11% share the care of their children equally with the mother (Peacey & Hunt, 2008). Sixty-nine percent of male employees say the demands of their job interfere with family; and 29% say the demands of family interfere with work (Lancaster University Management School/Working Families, 2010). Their father not using paternity leave increases the likelihood of a three year old child having developmental problems (Dex & Ward, 2007) which of course translates into parenting stress for both parents. Parenting stress in fathers is no less destructive of work performance than other forms of stress which, as is well known, are linked with absenteeism, decreased work commitment, impaired performance /productivity, higher staff turnover, increased accidents/unsafe working, increased customer complaints & liability to legal claims/actions. A father’s worry about his relationship with his children, particularly teenagers, is a very strong predictor of his own ill health (and hence poor work performance). Substantial early involvement by fathers makes a good father-adolescent relationship far more likely, with high father involvement in childhood and adolescence correlated with lower adolescent risk behaviour (Bronte-Tinkew et al, 2006) including smoking (Menning, 2006) and criminality (Flouri, 2005). High father involvement and increasing father-teen closeness are associated with reduced psychological distress in adolescents of both sexes (Harris et al, 1998) and, consequently, more positive behaviour.

Fathers’ take up of paternity leave can ‘buffer’ families against separation and divorce. Family breakdown is very costly to employers. Fathers experiencing family breakdown typically perform poorly at work and are at high risk of unemployment. At least 50% of new fathers experience a serious decline in ‘couple happiness’ after their baby’s birth, from which their relationship may never recover (Cowan & Cowan, 2000; Belsky & Kelly, 1994). Taking substantial paternity/parental leave can ‘buffer’ couples against relationship decline. Sixty nine percent of UK fathers who took paternity leave said it improved the quality of family life (EHRC, 2009). Taking paternity leave was also linked with fathers’ higher levels of involvement in infant care (Tanaka & Waldfogel, 2007) which, in turn, usually translates into greater couple happiness: among cohabiting couples with newborns, both parents’ beliefs that father-involvement is important plus fathers’ actual involvement predict relationship stability (Hohmann-Marriott, 2006). Conversely, low father involvement is associated with high levels of women’s anger at their partners (Ross & Van Willigen, 1996) and low satisfaction among fathers (Craig & Sawriker, 2006). Take up of parental leave by Swedish fathers (the equivalent of Additional Paternity Leave in the UK) is linked to lower rates of separation/divorce (Olah, 2001). An important longitudinal US study which controlled for socioeconomic factors found fathers’ involvement in routine every day childcare plus play/school liaison throughout a child’s life to beyond adolescence, accounting for 21% of the variance in fathers’ marital happiness at midlife (Snarey, 1993).

Adoption Leave There exists however in the Basic Conditions of Employment Act (1997) no legal obligation on employers to grant an adoptive parent any leave after the adoption of a child(ren). Children’s Act 38 of 2005: Adoption 228. A child is adopted if the child has been placed in the permanent care of a person in terms of a court order that has the effects contemplated in section 242. Purposes of Adoption 229. The purposes of adoption are to(a) protect and nurture children by providing a safe, healthy environment with positive support; and (b) promote the goals of permanency planning by connecting children to other safe and nurturing family relationships intended to last a lifetime. In South Africa same-sex marriage has been legal since the Civil Union Act came into force on 30 November 2006. Three important court cases to consider: • Du Toit v Minister of Welfare and Population Development (2002) allowed same-sex couples to adopt children jointly • J and B v Director General, Department of Home Affairs (2003) allowed both partners to be recorded as the parents of a child conceived through artificial insemination. • MIA v State Information Technology Agency (Pty) Ltd the Labour court found that the respondent’s policy discriminates unfairly on the applicant and that he was in fact entitled to 4 months paid maternity leave.

Part E: Adoption benefits Right to adoption benefits 27. (1) Subject to section 14, only one contributor of the adopting parties is entitled to the adoption benefits contemplated in this Part in respect of each adopted child and only if— (a) the child has been adopted in terms of the Child Care Act, 1983 (Act No. 74 of 1983); (b) the period that the contributor was not working was spent caring for the child; (c) the adopted child is below the age of two; and (d) the application is made in accordance with the prescribed requirements and the provisions of this Part. (2) The entitlement contemplated in subsection (1) commences on the date that a competent court grants an order for adoption in terms of the Child Care Act, 1983 (Act No. 74 of 1983). (3) Subject to subsection (4), the contributor must be paid the difference, if any, between any adoption benefit paid to that contributor in terms of any other law or any collective agreement or contract of employment for the period contemplated in section 19(2) and the maximum benefit payable in terms of section 12(2). (4) When taking into account any leave paid to the contributor in terms of any other law or any collective agreement or contract of employment, the benefit may not be more than the remuneration the employer would have paid the contributor if the contributor had been at work. Although according to Section 5 of the Unemployment Insurance Contributions Act No 4 of (2002) every employer and every employee to whom this Act applies must, on a monthly basis, contribute to the Unemployment Insurance Fund, only a contributor who is pregnant is entitled to the maternity benefits according to section 24 (1) of the Unemployment Insurance Fund Act (2001) or only one contributor of the adopting parties is entitled to the adoption benefits contemplated in section 27(1).