Navigating the Intercultural Contexts of Contemporary Healthcare Delivery

- Slides: 31

Navigating the Intercultural Contexts of Contemporary Healthcare Delivery John J. Rief, Ph. D Assistant Professor Department of Communication & Rhetorical Studies Duquesne University

Learning Objectives § Defining and understanding the scope of cultural competence for the clinical setting [ubiquitous phrasing in the literature] § Considering various ways to develop cultural competence through education, experiential learning, and ongoing reflection § Developing skills in applying the concept of cultural competence to specific cases and discerning when the concept is both helpful and potentially insufficient

Some Preliminary Notes from Communication Theory

Medicine and Communication Brent D. Ruben: § “the dynamics of communication in health care contexts have been widely studied, and substantial efforts to improve provider communication skills have been implemented in a variety of settings. And yet, what is perhaps the most fundamental challenge in the translation of communication theory for improving health care remains. . . this persistent gap is, at least in part, a consequence of the way in which communication theory has been appropriated and integrated into health care discourse and practice” 1 § THE PROBLEM: “notions of ‘exchange’ or ‘sharing’ of information” 2 1 Brent D. Ruben, “Communication Theory and Health Communication Practice: The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same, ” Health Communication, Volume 31 (2016): 1 -11, 3; 2 Ruben, “Communication Theory and Health Communication Practice, ” 3.

The Scope of the “Rhetoric of Medicine” Kenneth Burke: “we could observe that even the medical equipment of a doctor’s office is not to be judged purely for its diagnostic usefulness, but also has a function in the rhetoric of medicine. Whatever it is as apparatus, it also appeals as imagery; and if a man has been treated to a fulsome series of tappings, scrutinizings, and listenings, with the aid of various scopes, meters, and gauges, he may feel content to have participated as a patient in such histrionic action, though absolutely no material thing has been done for him, whereas he might count himself cheated if he were given a real cure, but without the pageantry. ” 3 3 Kenneth Burke, A Rhetoric of Motives (New York, NY: Prentice-Hall, Inc. , 1952), 171; on the scope of rhetoric in the area of medicine, see Lisa Meloncon and J. Blake Scott, “Manifesting a Scholarly Dwelling Place in RHM, ” Rhetoric of Health & Medicine, Volume 1, Numbers 1 -2, pp. i-x (http: //journals. upress. ufl. edu/rhm/article/view/670/696).

Identifying with Patients Kenneth Burke: “Identification is affirmed with earnestness precisely because there is division. Identification is compensatory to division. ” 4 “But put identification and division ambiguously together, so that you cannot know for certain just where one ends and the other begins, and you have the characteristic invitation to rhetoric. ” 5 4 Burke, A Rhetoric of Motives, 22; 5 Burke, A Rhetoric of Motives, 25.

What is Cultural Competence? Definitions, Concepts, & Revisions

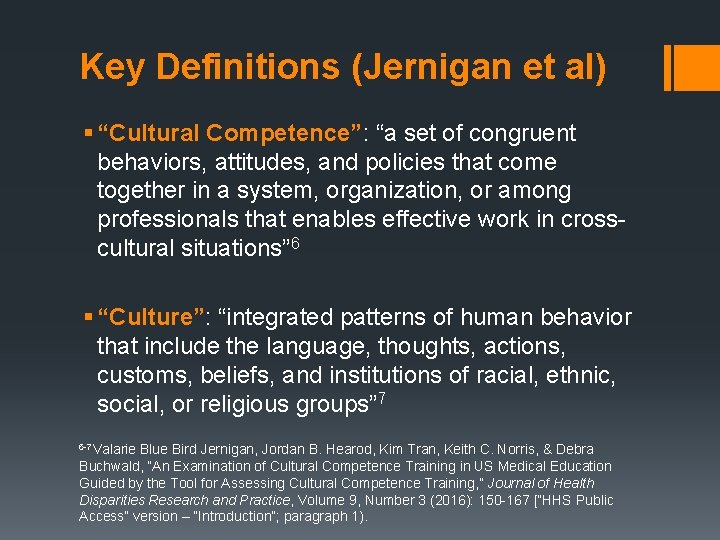

Key Definitions (Jernigan et al) § “Cultural Competence”: “a set of congruent behaviors, attitudes, and policies that come together in a system, organization, or among professionals that enables effective work in crosscultural situations” 6 § “Culture”: “integrated patterns of human behavior that include the language, thoughts, actions, customs, beliefs, and institutions of racial, ethnic, social, or religious groups” 7 6 -7 Valarie Blue Bird Jernigan, Jordan B. Hearod, Kim Tran, Keith C. Norris, & Debra Buchwald, “An Examination of Cultural Competence Training in US Medical Education Guided by the Tool for Assessing Cultural Competence Training, ” Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice, Volume 9, Number 3 (2016): 150 -167 [“HHS Public Access” version – “Introduction”; paragraph 1).

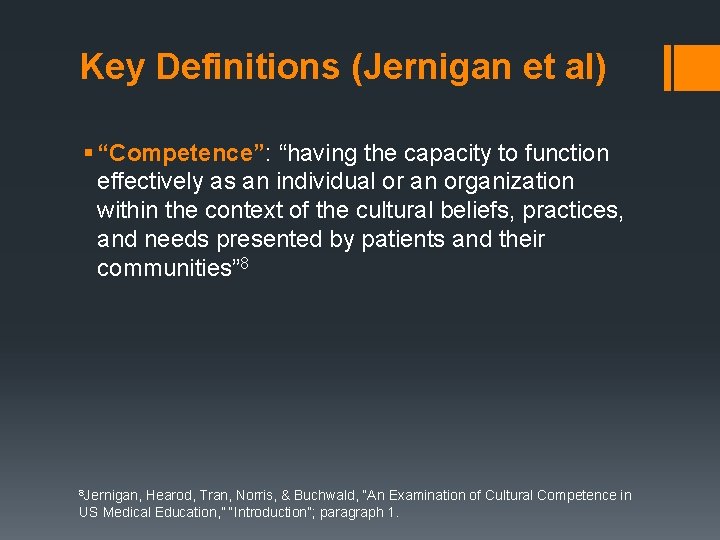

Key Definitions (Jernigan et al) § “Competence”: “having the capacity to function effectively as an individual or an organization within the context of the cultural beliefs, practices, and needs presented by patients and their communities” 8 8 Jernigan, Hearod, Tran, Norris, & Buchwald, “An Examination of Cultural Competence in US Medical Education, ” “Introduction”; paragraph 1.

Dialogue § How would you challenge, redefine, expand, or otherwise revise these definitions? § Cultural Competence § Culture § Competence

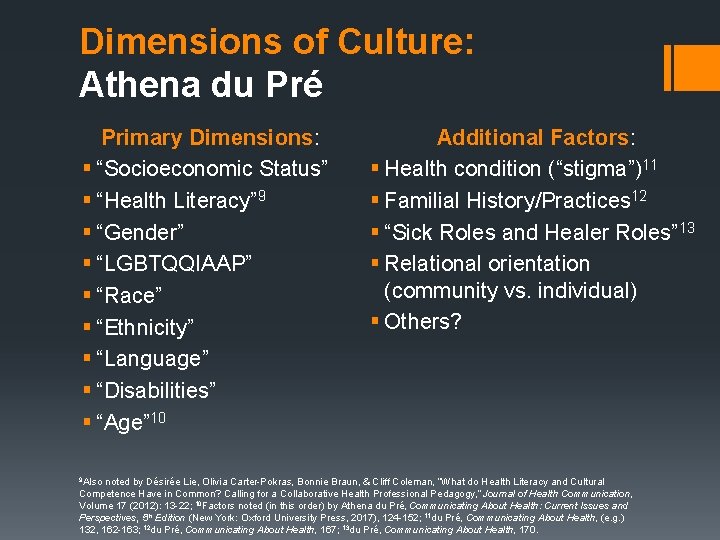

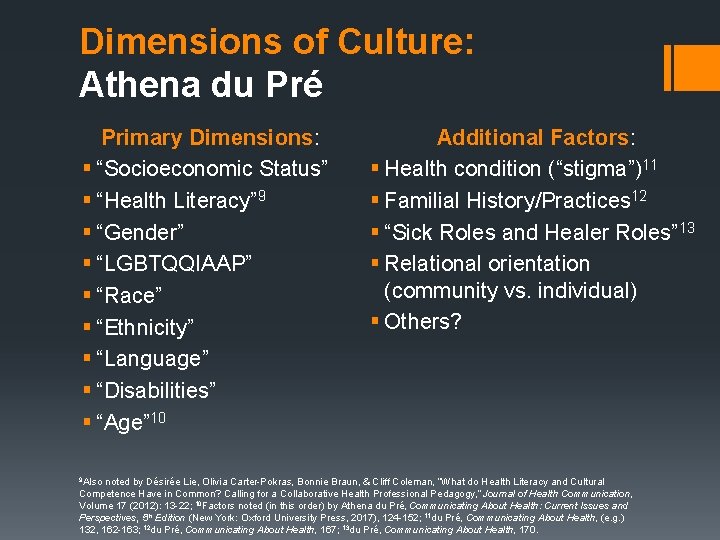

Dimensions of Culture: Athena du Pré Primary Dimensions: § “Socioeconomic Status” § “Health Literacy” 9 § “Gender” § “LGBTQQIAAP” § “Race” § “Ethnicity” § “Language” § “Disabilities” § “Age” 10 9 Also Additional Factors: § Health condition (“stigma”)11 § Familial History/Practices 12 § “Sick Roles and Healer Roles” 13 § Relational orientation (community vs. individual) § Others? noted by Désirée Lie, Olivia Carter-Pokras, Bonnie Braun, & Cliff Coleman, “What do Health Literacy and Cultural Competence Have in Common? Calling for a Collaborative Health Professional Pedagogy, ” Journal of Health Communication, Volume 17 (2012): 13 -22; 10 Factors noted (in this order) by Athena du Pré, Communicating About Health: Current Issues and Perspectives, 5 th Edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), 124 -152; 11 du Pré, Communicating About Health, (e. g. ) 132, 162 -163; 12 du Pré, Communicating About Health, 167; 13 du Pré, Communicating About Health, 170.

“Intersectionality” 14 § du Pré: “Intersectionality. . . proposes that a person’s social position emerges within the interface of micro-level personal identities and macro-level sociocultural patterns. . . Each of these levels is dynamic and complex. Personal identify may reflect age, race, sexual orientation, physical ability, and education. . . Sociocultural variables may include sexism, racism, power, resources, public policies, and so on. ” 15 § Concept received significant attention after Kimberlé Crenshaw’s work in the 1980 s/90 s 16 14 -15 du Pré, Communicating About Health, 124 -125. ; 16(as cited in du Pré) Kimberlé Crenshaw, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics, ” University of Chicago Legal Forum, Volume 1989, Issue 1 (1989): 139 -167; Kimberelé Crenshaw, “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color, ” Stanford Law Review, Volume 43, Number 6 (1991): 1241 -1299; see also bell hooks, Ain’t I A Woman: black women and feminism (Gloria Watkins, 1981).

Be Careful with Terms & Concepts: Fundamental Point du Pré: “culture is not a fixed construct, but an evolving and complex one. Even within the same culture, what is considered appropriate for one person, in one situation, may be unacceptable for another. No amount of cultural knowledge allows us to predict accurately how an individual will think or behave. ” 17 17 du Pré, Communicating About Health, 154.

Medicine as Professional Culture § Overall cultural composition (Jernigan et al): “non. Hispanic Whites comprise 75% of the physician workforce and 61% of medical school faculty” 18 § Professional practices and modes of communication (expertise)19 § Montgomery: “Biomedical discourse” and “biomilitarism” 20 § Illness vs. disease 21 18 Jernigan, Hearod, Tran, Norris, & Buchwald, “An Examination of Cultural Competence in U. S. Medical Education, ” “Conclusion”; paragraph 1. They cite the Association of American Medical Colleges on this statistic; see also du Pré, Communicating About Health, 135. 19 Jernigan, Hearod, Tran, Norris, & Buchwald, “An Examination of Cultural Competence Training in U. S. Medical Education, ” ”Results-Program Descriptions-Definition and application of cultural competence, ” paragraph 2; Ruben, “Communication Theory and Health Communication Practice, ” 5; Lie, Carter-Pokras, Braun, & Coleman, “What do Health Literacy and Cultural Competence Have in Common? 15; (as cited in Jernigan et al. ) Paritosh Kaul, & Gretchen Guiton, “Responding to the Challenges of Teaching Cultural Competency, ”Medical Education, Volume 44 (2010): 506; Désirée Lie, Johanna Shapiro, Felicia Cohn, and Wadie Najm, “Reflective Practice Enriches Clerkship Students’ Cross-Cultural Experiences, ” Journal of General Internal Medicine, Volume 25 (Supplement 2) (2009): s 119 -s 125; du Pré, Communicating About Health, 128; 20 Scott L. Montgomery, “Illness and Image: On the Contents of Biomedical Discourse, ” in The Scientific Voice (New York, NY: The Guildford Press, 1996), 134 -195; see also du Pré, Communicating About Health, 168 -169; 21 Montgomery, “Illness and Image, ” 189 (FN 2); Arthur Kleinman, The Illness Narratives: Suffering, Healing and the Human Condition (Basic Books, 1998).

Patient-Provider Communication as Intercultural Ruben: “health communication interactions are most appropriately viewed as cross-cultural encounters. . . Differences in vocabulary, rate of speaking, age, background, familiarity with medical technology, education, physical capability, and experience can create a huge cultural and communication chasm – all too easily overlooked because all parties speak the ‘same’ language. ” 22 22 Ruben, “Communication Theory and Health Communication Practice, ” 5.

Medicine as an Intercultural Profession § Increased specialization, differing norms and approaches to care 23 § Jackson: “heterogenous expertise” 24 § Lie et al: “There is thus a need for each profession to be knowledgeable of its own and others’ cultures, beliefs, practices, jargon, assumptions, and strategies. ” 25 23 Lie, Carter-Pokras, Braun, & Coleman, “What Do Health Literacy and Cultural Competence Have in Common? ” 18; 24 Sally Jackson, “Design Thinking in Argumentation Theory and Practice, ” Argumentation, Volume 29 (2015): 243 -263, 258 -259; 25 Lie, Carter-Pokras, Braun, & Coleman, “What Do Health Literacy and Cultural Competence Have in Common? ” 18.

Developing Cultural Competence Strategies, Approaches, and Conceptual Interruptions

Impediments to Achieving Cultural Competence § Pursuit of mastery (not possible) § Unclear whether cultural competence education impacts behavior long-term § Difficult to cultivate changes to medical practice rooted in appreciating cultural difference 26 § Kaul & Guiton: “Student apathy and resistance” 27 26 For first three bullet points, see Jernigan, Hearod, Tran, Norris, & Buchwald, “An Examination of Cultural Competence Training in U. S. Medical Education, ” “Discussion-Defining and Measuring Outcomes”; paragraphs 1 -2; “Provider Barriers and Resistance to Training”; paragraphs 1 -2; 27 Kaul & Guiton, “Responding to the challenges of teaching cultural competency, ” 506; see also Jernigan, Hearod, Tran, Norris, & Buchwald, “An Examination of Cultural Competence Training in U. S. Medical Education, ” “Discussion-Provider barriers and resistance to training”; paragraph 1.

Benefits to Developing Cultural Competence (Ethics and Outcomes) § Essential element of ethical communication practices in the clinical setting § Fundamentally related to justice 28 § Could improve quality of care and outcomes (but additional research needed)29 28 I am applying the term “justice” here based on the work of Beauchamp and Childress. See Tom L. Beauchamp & James F. Childress, Principles of Biomedical Ethics, 6 th Edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 240 -281; 29 Jernigan, Hearod, Tran, Norris, & Buchwald, “An Examination of Cultural Competence Training in U. S. Medical Education, ” “Discussion-Defining and measuring outcomes”; paragraph 2.

Benefits to Developing Cultural Competence (Cost & Access) § du Pré: “Avoidable health care costs attributed to health literacy are estimated at $106 billion to $238 billion a year in the United States – enough to insure 40 million people” 30 § Schiavo: “excess medical expenditures due to health inequities in the U. S. accounted for 31% (or approximately $229 billion) of total medical expenditures over a 3 -year period. ” 31 30 du Pré, Communicating About Health, 129; 31 Renata Schiavo, “Addressing health disparities in clinical settings: Population health, quality of care, and communication, ” Journal of Communication in Healthcare, Volume 8, Number 3 (2015): 163 -166, 164.

Cultural Competence Education § Papadopoulos et al: § “Cultural Awareness” § “Cultural Knowledge” § “Cultural Sensitivity” 32 § Let’s define these terms and discuss ways to develop each. . . 32 Irena Papadopoulos, Sue Shea, Georgina Taylor, Alfonso Pezzella, & Laura Foley, “Developing tools to promote culturally competent compassion, courage, and intercultural communication in healthcare, ” Journal of Compassionate Health Care, Volume 3, Number 2 (2016): https: //jcompassionatehc. biomedcentral. com/track/pdf/10. 1186/s 40639 -016 -0019 -6, “Methods-Guiding Principles for structuring the tools-PTT Model”; paragraph 1.

Strategies for Systemic Change § “healthcare-community partnerships” 33 § “Institutional” and “public advocacy” 34 § “Recruitment and retention” of diverse staff (enhanced by the practice of cultural competence)35 § Health information technology (especially useful for low SES communities? )36 33 Schiavo, “Addressing health disparities in clinical settings, ” 164; 34 Schiavo, “Addressing health disparities in clinical settings, ” 165; 35 Papadopoulos, Shea, Taylor, Pezzella, & Foley, “Developing tools to promote culturally competent compassion, ” “Background”; paragraphs 5 -6; 36 du Pré, Communicating About Health, p. 126.

Conceptual Interruption: “Compassion” Papadopoulos et al § “Culturally competent compassion”: “‘a human quality of understanding the suffering of others and wanting to do something about it using culturally appropriate and acceptable nursing interventions. This takes into consideration both the patients’ and the carers’ cultural backgrounds as well as the context in which care is given. ’” 37 § “Culturally Competent Courage”: “‘a virtue which enables us to do the right thing for the people we care for, to speak up when we have concerns and to have the personal strength and vision to innovate and to embrace new ways of working’” 38 37 Papadopoulos as cited in Papadopoulos, Shea, Taylor, Pezzella, & Foley, “Developing tools to promote culturally competent compassion, ” “Background”; paragraph 8; 38“NHS Commissioning Board” as cited in Papadopoulos, Shea, Taylor, Pezzella, & Foley, “Developing tools to promote culturally competent compassion, ” “Methods”; paragraph 1.

Conceptual Interruption: “Cultural Humility” Jernigan et al § “Cultural Humility”: “posits that one can never be fully competent in another person’s culture. Instead, one must undertake a lifelong commitment involving self-evaluation, self-critiquing, and redressing power imbalances” 39 39 Jernigan, Hearod, Tran, Norris, & Buchwald, “An Examination of Cultural Competence Training in U. S. Medical Education, ” “Discussion-Alternative Approaches”; paragraph 1.

Cultural Competence Cases Dialogue and Skills Development

Measuring Communication Effectiveness Aristotle: “For what is itself indefinite can only be measured by an indefinite standard, like the leaden rule used by Lesbian builders; just as that rule is not rigid but can be bent to the shape of the stone, so a special ordinance is made to fit the circumstances of the case. ” 40 40 Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, in the Loeb Classical Library, Volume XIX, translated by H. Rackham (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1926/2003), V. x. 7 -8.

Encountering Cases Ludwig Wittgenstein: “We have got on to slippery ice where there is no friction and so in a certain sense the conditions are ideal, but also, just because of that, we are unable to walk. We want to walk: so we need friction. Back to the rough ground!” 41 41 Ludwig Wittgensten, Philosophical Investigations, 2 nd Edition, translated by G. E. M. Anscombe (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 1953/2000), 107 (p. 46 e); (use here inspired by) Joseph Dunne, Back to the Rough Ground: Practical Judgment and the Lure of Technique (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1993); see also Albert R. Jonsen & Stephen Toulmin, The Abuse of Casuistry: A History of Moral Reasoning (Berkley, CA: University of California Press, 1988/1989).

Case 1: Overweight Patient Mrs. P is a 35 -year-old primary care patient. She is pre-diabetic, hypertensive, and overweight. Her PCP, Dr. J, elects to counsel her on weight loss through lifestyle change as one way to address her worsening health problems. When Dr. J. broaches the subject of weight, Mrs. P seems taken aback and then offended. She assures Dr. J. that her weight is perfectly normal and that there must be some other approach to treatment. When Dr. J. persists with the conversation, Mrs. P refuses to engage and leaves the office as quickly as possible. She has not replied to follow-up calls.

Case 2: Health Literacy Lie et al: “Mrs. Smith is a 50 -year-old U. S. -born office clerk with no family history of breast cancer. She believes that mammograms are performed for diagnosis of breast cancer when a breast lump is detected by examination, but has not shared this belief with her provider. When her primary care provider gives her a form for a mammogram after a well-woman visit, she discards it outside the medical office as being irrelevant to her. ” 42 42 Lie, Carter-Pokras, Braun, & Coleman, “What Do Health Literacy and Cultural Competence Have in Common? ” p. 17.

Case 3: Cultural Perceptions of Adequate Care Mr. D is an 80 -year-old African American male. He was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer about 1 year ago. One month ago, he was admitted to the hospital with severe pain and weakness. His condition has deteriorated and he is now unconscious and relies on various forms of life support. His care team has determined that ongoing life support is only delaying the inevitable. They suggest that the family consider removing “lifesustaining care to let nature take its course. ” Mr. D’s family is surprised at the suggestion and immediately asks why the care team has elected to stop treating him.

Case 4: Patient-Provider Communication as Intercultural Mr. S is an 79 -year-old man with an elevated PSA level and a detectable lump on his prostate. His urologist, Dr. Y, has been monitoring his prostate and PSA screenings for the past ten years. He is relatively certain that, though Mr. S likely has cancer, it is of a form that is unlikely to cause symptoms or early death given its slow growth rate. Though his recent results indicate the possible presence of cancer, he has advised Mr. S not have a biopsy. In response, Mr. S states “you must think my life is already over. ” Mr. S and his wife request a biopsy. Dr. Y explains his reasoning to Mr. S and his wife one more time, but schedules the procedure anyway.

Intercultural communication in contexts

Intercultural communication in contexts Sports medicine definition

Sports medicine definition Healthcare and the healthcare team chapter 2

Healthcare and the healthcare team chapter 2 The term that stresses the social contexts in which

The term that stresses the social contexts in which Model komunikasi tubbs dan moss

Model komunikasi tubbs dan moss Writing in professional contexts

Writing in professional contexts The srs document is useful in various contexts

The srs document is useful in various contexts Shape matching and object recognition using shape contexts

Shape matching and object recognition using shape contexts Uefap

Uefap Global context fairness and development

Global context fairness and development Teachers in crisis contexts

Teachers in crisis contexts Shape matching and object recognition using shape contexts

Shape matching and object recognition using shape contexts Introduction to healthcare delivery systems

Introduction to healthcare delivery systems Regions of the body

Regions of the body Navigating the art world

Navigating the art world What is the purpose of liquid in the capsule of a compass?

What is the purpose of liquid in the capsule of a compass? Digital landscape model

Digital landscape model Navigating gdpr compliance on aws

Navigating gdpr compliance on aws Trigonometry in navigation

Trigonometry in navigation Navigating gdpr compliance on aws

Navigating gdpr compliance on aws Components of ads accenture

Components of ads accenture Intercultural development continuum

Intercultural development continuum Barriers of intercultural communication

Barriers of intercultural communication Linear vs relational worldview

Linear vs relational worldview Branches of rhetoric

Branches of rhetoric Define intercultural competence

Define intercultural competence Intercultural communication conclusion

Intercultural communication conclusion Verbal intercultural communication examples

Verbal intercultural communication examples Example of a low context culture

Example of a low context culture Intercultural praxis definition

Intercultural praxis definition Decálogo para una educación intercultural

Decálogo para una educación intercultural Intercultural capability vic curriculum

Intercultural capability vic curriculum