Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly Monopolistic Competition Industry Structure

- Slides: 24

Monopolistic Competition and Oligopoly

Monopolistic Competition Industry Structure Industry of most common type of firm: retailing, services A bit like both monopoly and competition � Like monopoly: D downward-sloping, MR steeper & below Product differentiation source of market power Can raise price without losing all its sales But firm’s demand more elastic than market demand � Like competition: fairly easy entry, low entry barriers Entry achieved by copying differentiation Entry if XS profits: demand shift back, long-run = 0 Result: Variety but at cost of Excess Capacity in

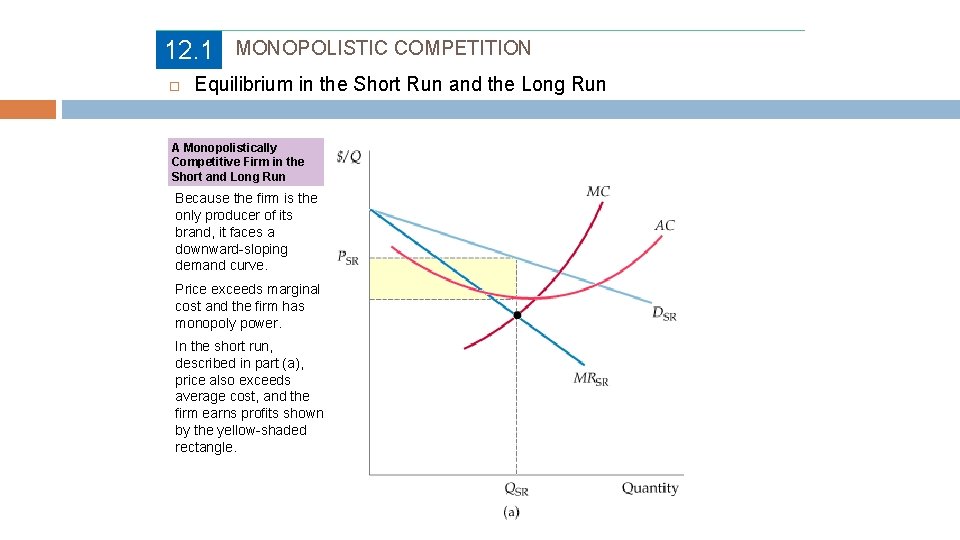

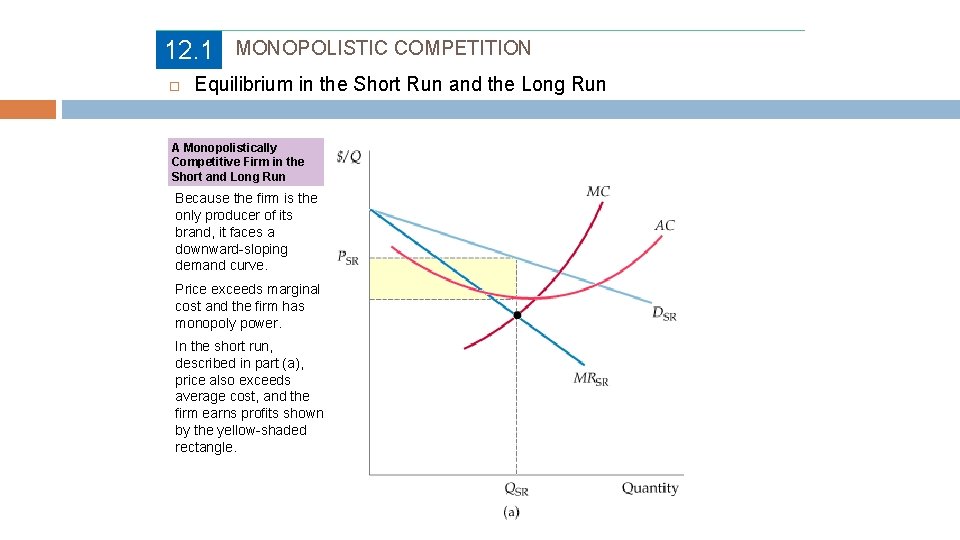

12. 1 MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION Equilibrium in the Short Run and the Long Run A Monopolistically Competitive Firm in the Short and Long Run Because the firm is the only producer of its brand, it faces a downward-sloping demand curve. Price exceeds marginal cost and the firm has monopoly power. In the short run, described in part (a), price also exceeds average cost, and the firm earns profits shown by the yellow-shaded rectangle.

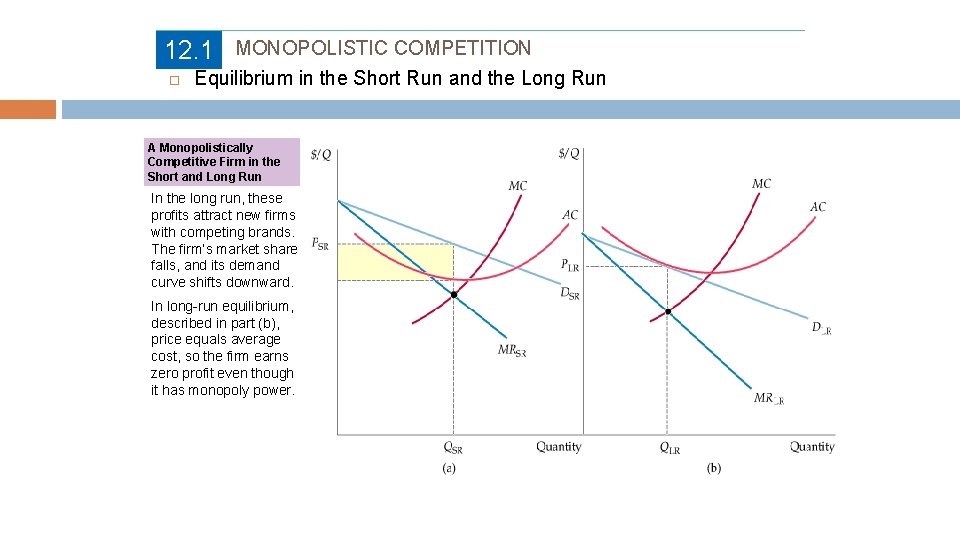

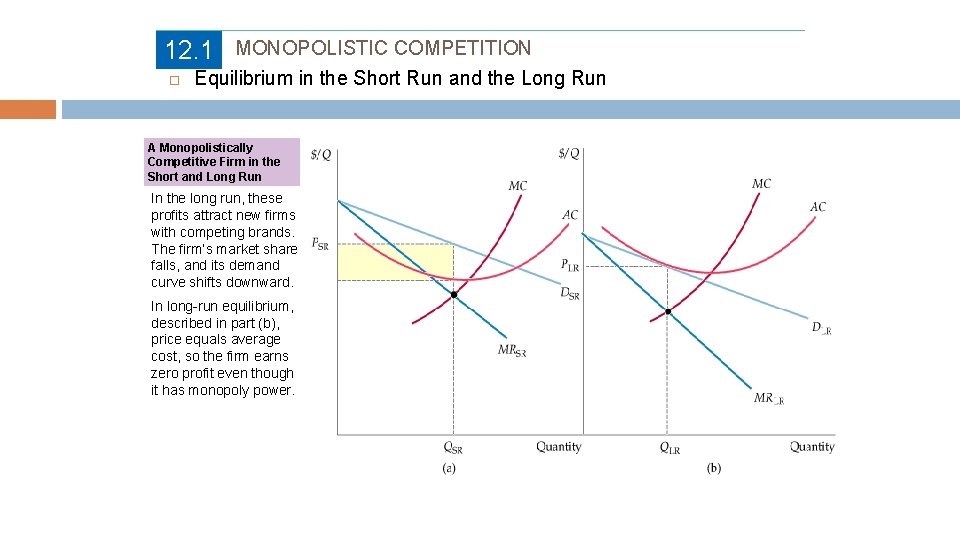

12. 1 MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION Equilibrium in the Short Run and the Long Run A Monopolistically Competitive Firm in the Short and Long Run In the long run, these profits attract new firms with competing brands. The firm’s market share falls, and its demand curve shifts downward. In long-run equilibrium, described in part (b), price equals average cost, so the firm earns zero profit even though it has monopoly power.

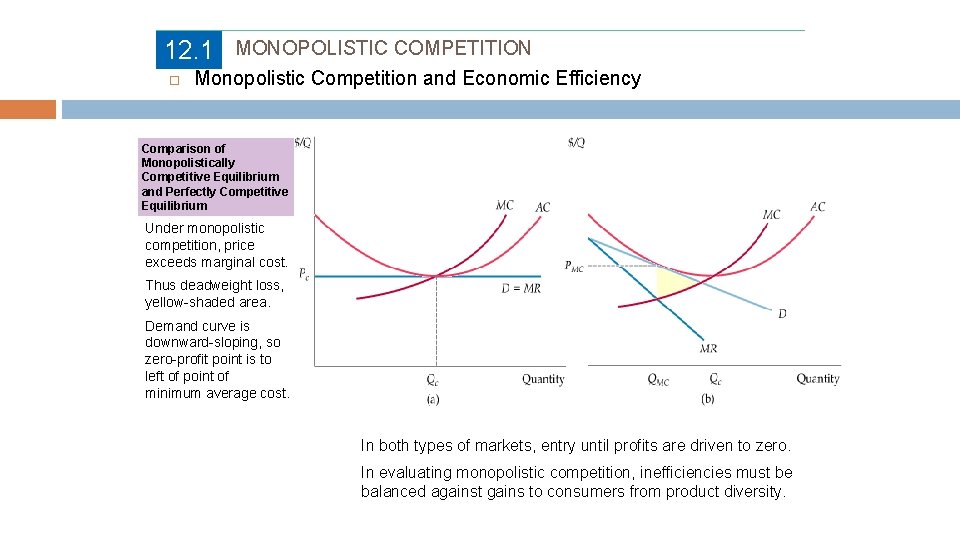

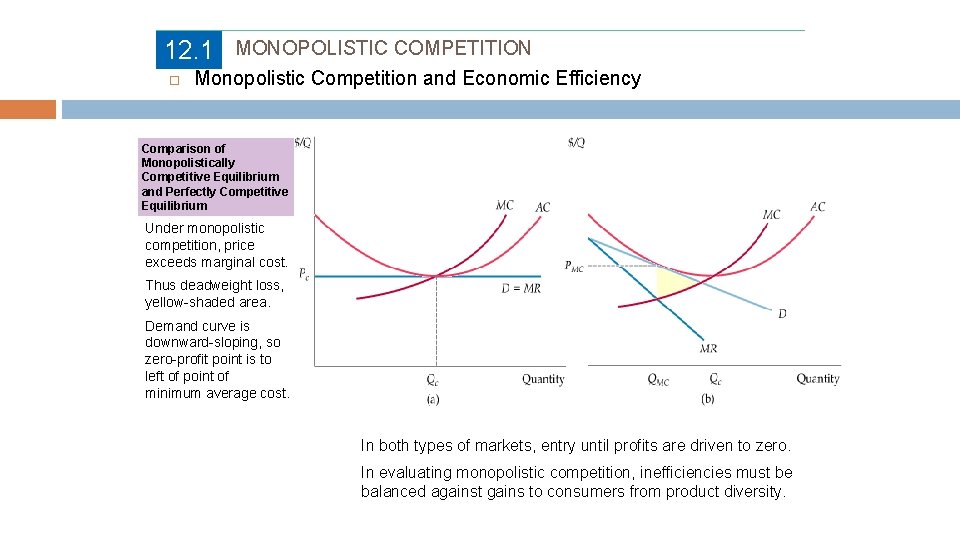

12. 1 MONOPOLISTIC COMPETITION Monopolistic Competition and Economic Efficiency Comparison of Monopolistically Competitive Equilibrium and Perfectly Competitive Equilibrium Under monopolistic competition, price exceeds marginal cost. Thus deadweight loss, yellow-shaded area. Demand curve is downward-sloping, so zero-profit point is to left of point of minimum average cost. In both types of markets, entry until profits are driven to zero. In evaluating monopolistic competition, inefficiencies must be balanced against gains to consumers from product diversity.

Product Differentiation A type of non-price behavior Basis for Monopolistic Competition, but also in some types of Oligopoly (but not competition or monopoly) Four sources of product differentiation: � Product attributes: quality, performance, style, size, etc. � Associated with product : service, warrantee, hours, etc. � Location: access, neighborhood, agglomeration � Perception: advertising, promotion, word-of-mouth,

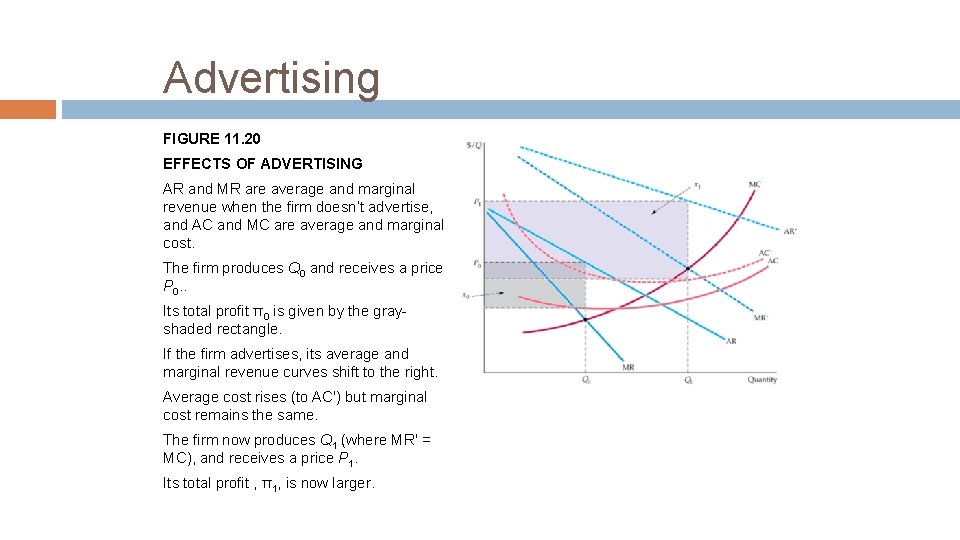

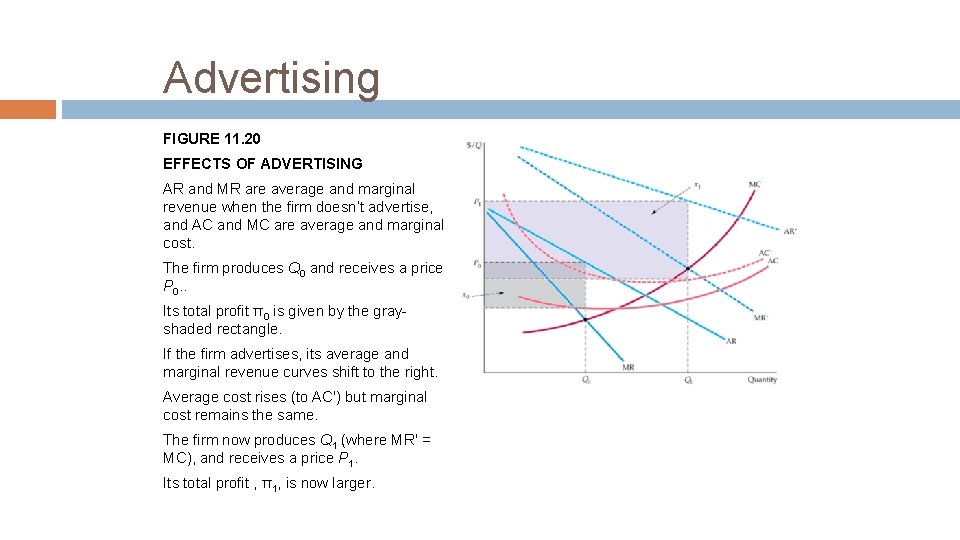

Advertising FIGURE 11. 20 EFFECTS OF ADVERTISING AR and MR are average and marginal revenue when the firm doesn’t advertise, and AC and MC are average and marginal cost. The firm produces Q 0 and receives a price P 0. . Its total profit π0 is given by the grayshaded rectangle. If the firm advertises, its average and marginal revenue curves shift to the right. Average cost rises (to AC′) but marginal cost remains the same. The firm now produces Q 1 (where MR′ = MC), and receives a price P 1. Its total profit , π1, is now larger.

The Optimal Level of Advertising The price P and advertising expenditure A to maximize profit, is given by: π = PQ(P, A)-C(Q)-A In figure 11. 20 on the previous slide, we saw that advertising leads to increased output. But increased output in turn means increased production costs, and this must be taken into account when comparing the costs and benefits of an extra dollar of advertising. The firm should advertise up to the point that = full marginal cost of advertising (11. 3)

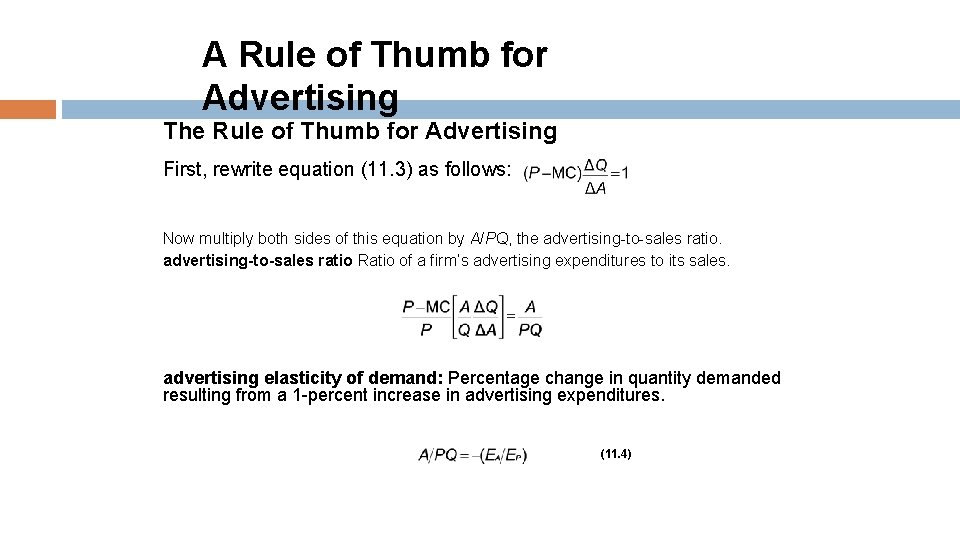

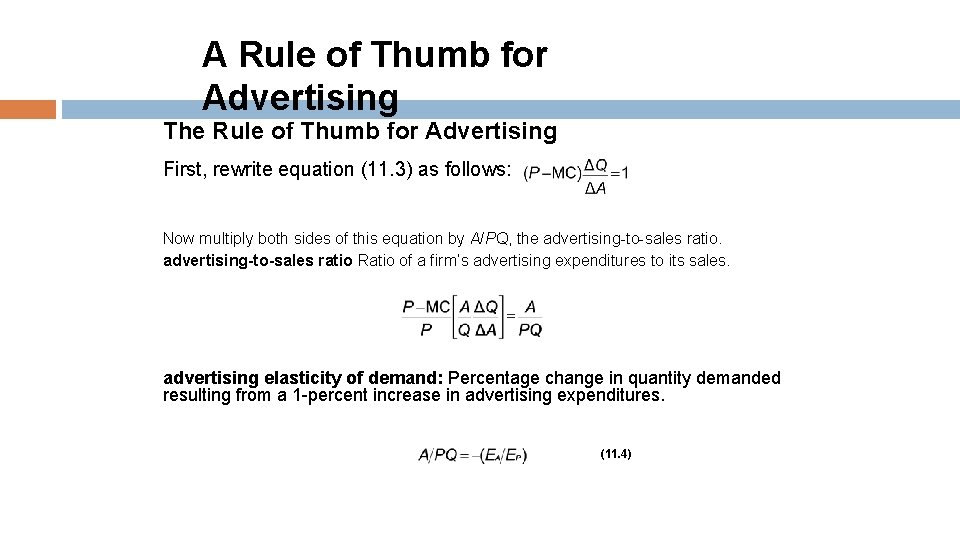

A Rule of Thumb for Advertising The Rule of Thumb for Advertising First, rewrite equation (11. 3) as follows: Now multiply both sides of this equation by A/PQ, the advertising-to-sales ratio Ratio of a firm’s advertising expenditures to its sales. advertising elasticity of demand: Percentage change in quantity demanded resulting from a 1 -percent increase in advertising expenditures. (11. 4)

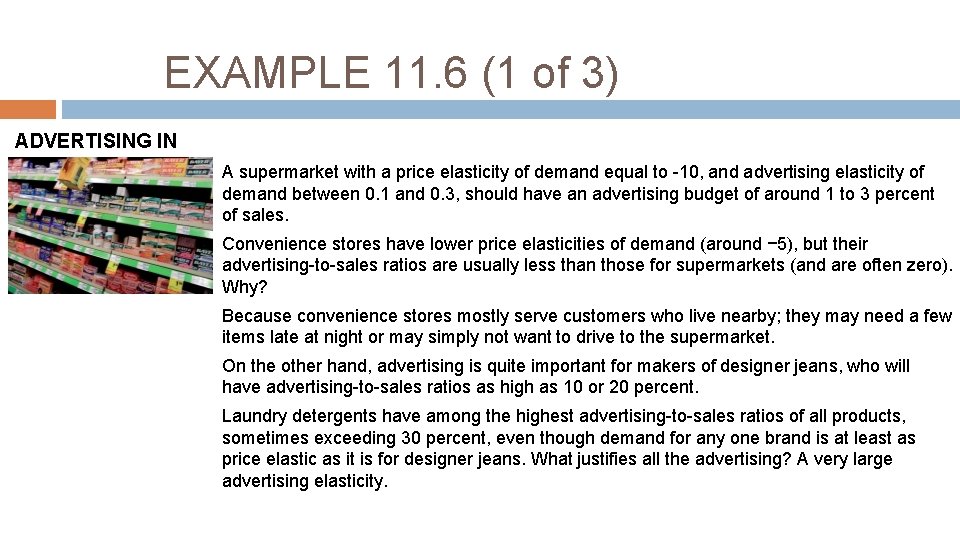

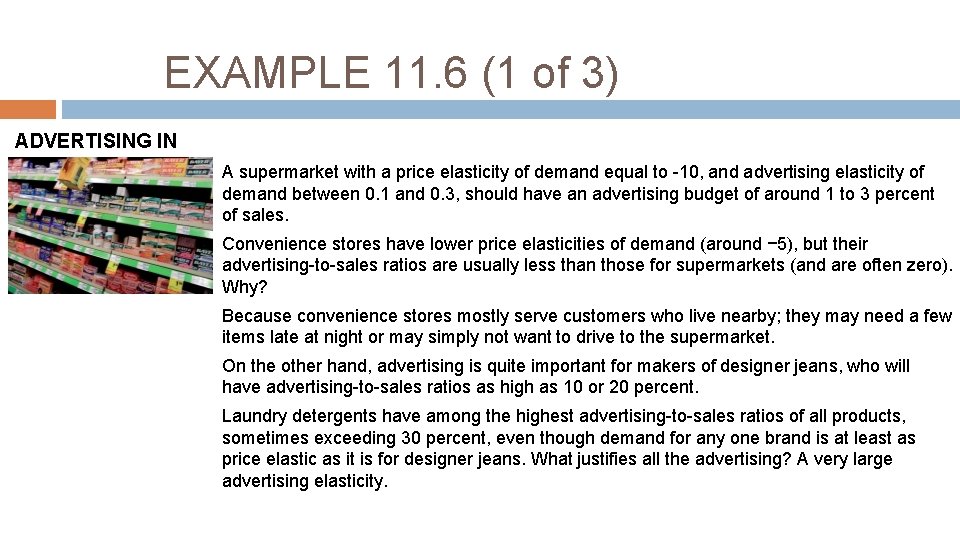

EXAMPLE 11. 6 (1 of 3) ADVERTISING IN PRACTICE A supermarket with a price elasticity of demand equal to -10, and advertising elasticity of demand between 0. 1 and 0. 3, should have an advertising budget of around 1 to 3 percent of sales. Convenience stores have lower price elasticities of demand (around − 5), but their advertising-to-sales ratios are usually less than those for supermarkets (and are often zero). Why? Because convenience stores mostly serve customers who live nearby; they may need a few items late at night or may simply not want to drive to the supermarket. On the other hand, advertising is quite important for makers of designer jeans, who will have advertising-to-sales ratios as high as 10 or 20 percent. Laundry detergents have among the highest advertising-to-sales ratios of all products, sometimes exceeding 30 percent, even though demand for any one brand is at least as price elastic as it is for designer jeans. What justifies all the advertising? A very large advertising elasticity.

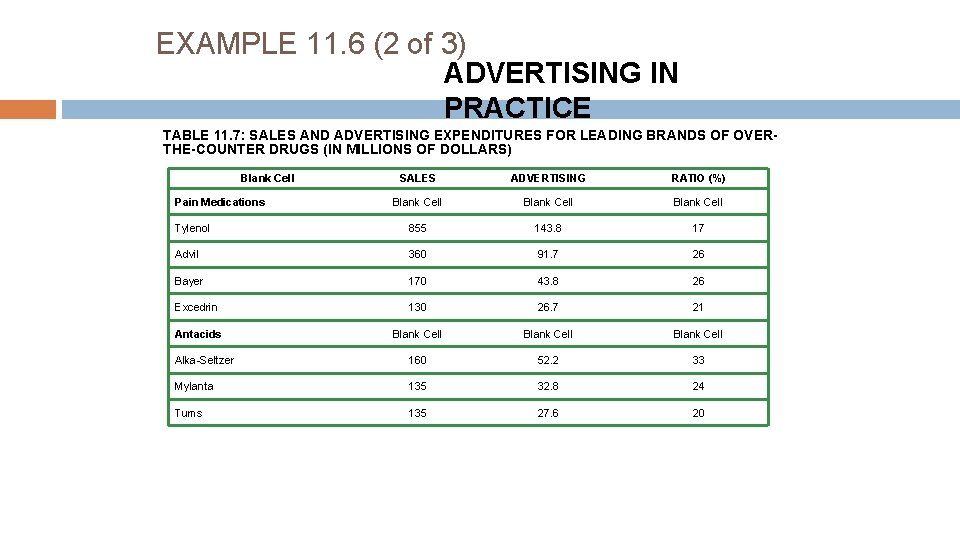

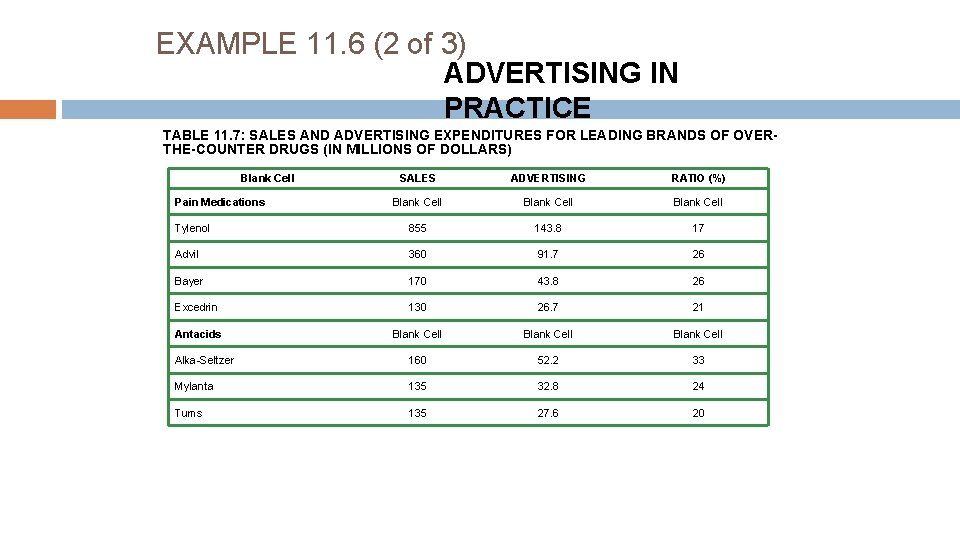

EXAMPLE 11. 6 (2 of 3) ADVERTISING IN PRACTICE TABLE 11. 7: SALES AND ADVERTISING EXPENDITURES FOR LEADING BRANDS OF OVERTHE-COUNTER DRUGS (IN MILLIONS OF DOLLARS) Blank Cell SALES ADVERTISING RATIO (%) Blank Cell Tylenol 855 143. 8 17 Advil 360 91. 7 26 Bayer 170 43. 8 26 Excedrin 130 26. 7 21 Antacids Blank Cell Alka-Seltzer 160 52. 2 33 Mylanta 135 32. 8 24 Tums 135 27. 6 20 Pain Medications

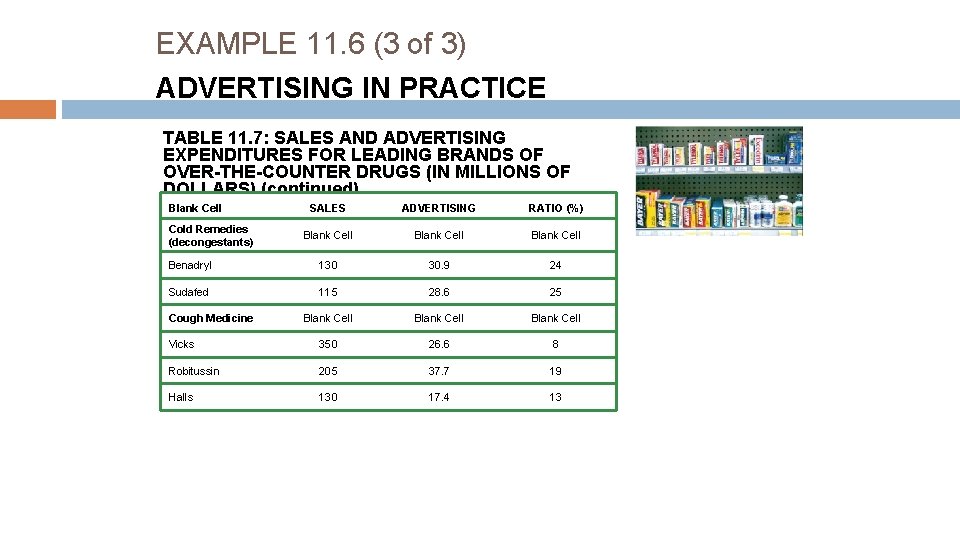

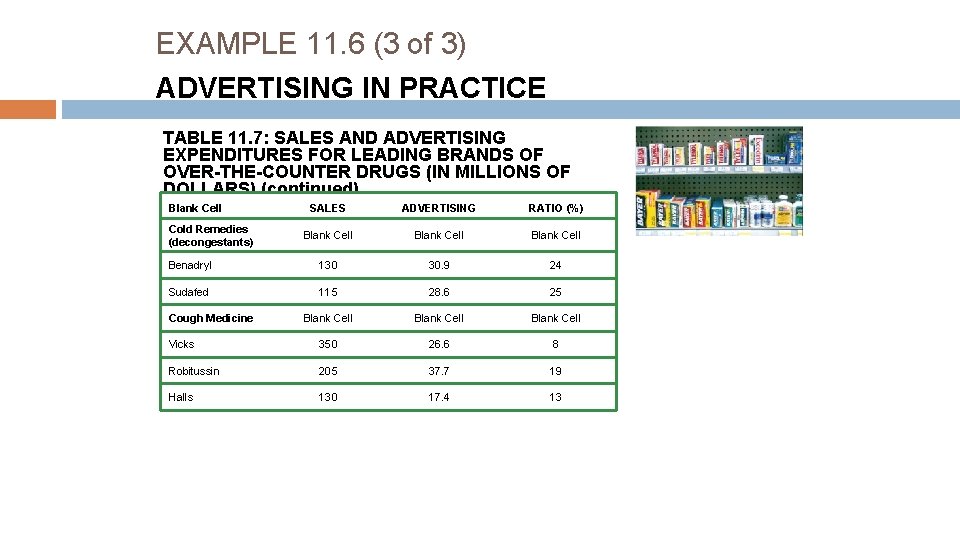

EXAMPLE 11. 6 (3 of 3) ADVERTISING IN PRACTICE TABLE 11. 7: SALES AND ADVERTISING EXPENDITURES FOR LEADING BRANDS OF OVER-THE-COUNTER DRUGS (IN MILLIONS OF DOLLARS) (continued) Blank Cell SALES ADVERTISING RATIO (%) Blank Cell Benadryl 130 30. 9 24 Sudafed 115 28. 6 25 Blank Cell Vicks 350 26. 6 8 Robitussin 205 37. 7 19 Halls 130 17. 4 13 Cold Remedies (decongestants) Cough Medicine

Oligopoly Industry Structure “Fewness” – few enough firms for recognized interdependence � If too many, actions of one firm has little impact on rest � Number of firms with large market shares � Size distribution of firms: industry concentration ratio Most important, largest segment of economy (Fortune 500) Non-price behavior: inefficient or raise entry barriers by – � Product differentiation: product proliferation strategy � Advertising/promotion: waste, intangible, risky investment � R&D, innovation, and patent strategies: blocks progress � Investment in production XS capacity: strategic sunk

Oligopoly Outcome Indeterminate Unlike Other Structures If collusive conduct: cartel achieves joint profit maximization Methods of Tacit collusion: If there’s a will, there’s a way � Price Leadership: one firm, rest follow, leader punish cheater � No Price Leader: Mark-Ups, Trade Associations, Focal Points Impediments to successful collusion � Too many firms or firms with different costs � High fixed costs in cyclically-unstable demand � Very large buyers or “lumpy” infrequent orders Constraint: Antitrust laws – “conspiracies in restraint of trade” � Triple damages penalty, “per se” illegal

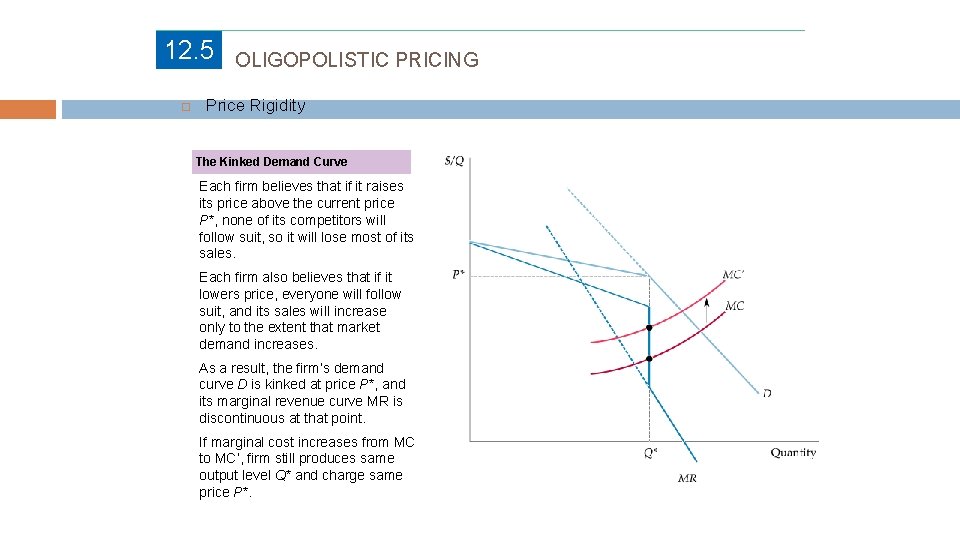

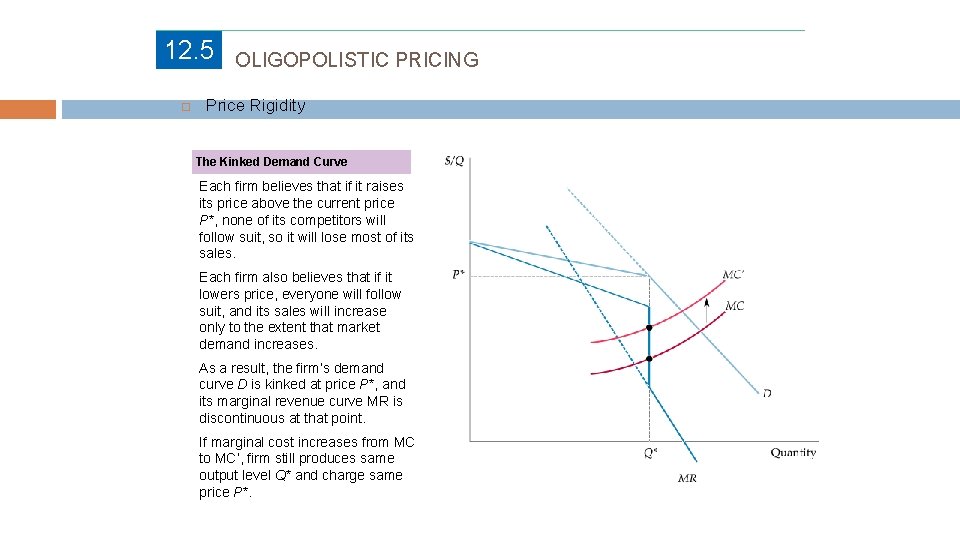

12. 5 OLIGOPOLISTIC PRICING Price Rigidity The Kinked Demand Curve Each firm believes that if it raises its price above the current price P*, none of its competitors will follow suit, so it will lose most of its sales. Each firm also believes that if it lowers price, everyone will follow suit, and its sales will increase only to the extent that market demand increases. As a result, the firm’s demand curve D is kinked at price P*, and its marginal revenue curve MR is discontinuous at that point. If marginal cost increases from MC to MC’, firm still produces same output level Q* and charge same price P*.

12. 5 OLIGOPOLISTIC PRICING Price Signaling and Price Leadership ● price signaling Form of implicit collusion in which a firm announces a price increase in the hope that other firms will follow suit. ● price leadership Pattern of pricing in which one firm regularly announces price changes that other firms then match. ● dominant firm Firm with a large share of total sales that sets price to maximize profits, taking into account the supply response of smaller firms.

12. 6 CARTELS In intercollegiate athletics, there are many firms and consumers, which suggests that the industry is competitive. But the persistently high level of profits in this industry is inconsistent with competition. This profitability is the result of monopoly power, obtained via cartelization. The cartel organization is the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA). The NCAA restricts competition in a number of important ways. To reduce bargaining power by student athletes, the NCAA creates and enforces rules regarding eligibility and terms of compensation. To reduce competition by universities, it limits the number of games that can be played each season and the number of teams that can participate in each division.

12. 6 CARTELS In 1996, the federal government allowed milk producers in the six New England states to cartelize. The cartel—called the Northeast Interstate Dairy Compact—set minimum wholesale prices for milk, and was exempt from the antitrust laws. The result was that consumers in New England paid more for a gallon of milk than consumers elsewhere in the nation. Studies have suggested that the cartel covering the New England states has caused retail prices of milk to rise by only a few cents a gallon. Why so little? The reason is that the New England cartel is surrounded by a fringe of noncartel producers—namely, dairy farmers in New York, New Jersey, and other states. Expanding the cartel, however, would have shrunk the competitive fringe, thereby giving the cartel a greater influence over milk prices.

Game Theory: Non-Cooperative Behavior

Game Theory Basics: Terms, Concepts Players: firms (2 -firm, multi-firm games) Strategic variables: price, output, investment, advertising, R&D, product differentiation Payoffs: profits, sales, market share Payoff Matrix: Nx. N matrix of payoffs for each player (e. g. , 2 x 2 for two player) correspond to all possible strategy combinations

Types of Games Zero Sum (actually, Constant Sum) Game: � your loss is my gain Prisoner’s Dilemma: � simultaneous non zero-sum game � jointly preferred position under perfect information � non-cooperative: prevents collusion and punishment Cournot Model: � Each player assumes other won’t respond Maximin Model: Players assume worst payoff

Types of Games Repeated Games: Develops trust, allows reprisals � Tit for Tat strategies: Signal to Noise difficulties � Last Hand/End Game: start from end, work back Sequential Games: Charlie Brown and Lucy’s football Dominant Strategy: optimal no matter what others do � Your dominant strategy arises out of knowing the dominant strategies of all other players

First Mover Advantage Firm Mover: pre-emptive commitment � Opposite of preserve all options until very last minute Works because you are often your own worst enemy � Others assume you’ll back down if not in own interest � Foreclose choices you seize first, leave others with dregs Only works if threats are “Credible” � Must create Sunk Cost commitment: “burn your bridges”

13. 6 THREATS, COMMITMENTS, AND CREDIBILITY How did Wal-Mart Stores succeed where others failed? The key was Wal-Mart’s expansion strategy. The conventional wisdom held that a discount store could succeed only in a city with a population of 100, 000 or more. Sam Walton disagreed and decided to open his stores in small Southwestern towns. The stores succeeded because Wal-Mart had created “local monopolies. ” Discount stores that had opened in larger cities were competing with other discount stores. Other discount chains realized that Wal-Mart had a profitable strategy, so the issue became who would get to each town first. Wal-Mart now found itself in a preemption game. To deter entry, the incumbent firm must convince any potential competitor that entry will be unprofitable. But what if you can make an irrevocable commitment that will alter your incentives once entry occurs— a commitment that will give you little choice but to charge a low price if entry occurs?

Chapter 7 section 3 monopolistic competition and oligopoly

Chapter 7 section 3 monopolistic competition and oligopoly Difference between perfect competition and monopoly market

Difference between perfect competition and monopoly market Is the coffee market perfectly competitive

Is the coffee market perfectly competitive Fast food oligopoly or monopolistic competition

Fast food oligopoly or monopolistic competition Lump sum subsidy

Lump sum subsidy Monopoly vs monopolistic competition

Monopoly vs monopolistic competition Monopoly vs oligopoly venn diagram

Monopoly vs oligopoly venn diagram Perfect competition vs monopolistic competition

Perfect competition vs monopolistic competition Characteristics of monopolistic competition

Characteristics of monopolistic competition Non price competition in oligopoly

Non price competition in oligopoly Banking industry structure and competition

Banking industry structure and competition Monopolistic competition pictures

Monopolistic competition pictures Market structure

Market structure Example of pure competition

Example of pure competition Difference perfect competition and monopoly

Difference perfect competition and monopoly Monopoly characteristics

Monopoly characteristics Monopolistic competition short run

Monopolistic competition short run Mr=mc monopoly

Mr=mc monopoly Price determination under monopolistic competition

Price determination under monopolistic competition Consumer surplus in monopolistic competition

Consumer surplus in monopolistic competition Monopolistic competition price

Monopolistic competition price Oligopoly characteristics

Oligopoly characteristics Monopolistic competition in long run

Monopolistic competition in long run Monopolistic competition short run

Monopolistic competition short run Consumer surplus in a monopoly

Consumer surplus in a monopoly