Monopoly Monopolistic Competition Oligopoly Based on Ch 21

Monopoly, Monopolistic Competition & Oligopoly Based on Ch. 21 & 22, Economics 9 th Ed , R. A. Arnold

Introduction In Ch. 21 and 22 we look at three other types of market: monopoly, monopolistic competition and oligopoly. The characteristics and conditions of these markets are compared with perfect competition (the perfectly competitive market). Remember: A seller in the perfectly competitive market is a price taker and hence P = MR i. e. the demand curve and the marginal revenue curve are the same. Also, P = MC. This is not the case in other markets as we shall see.

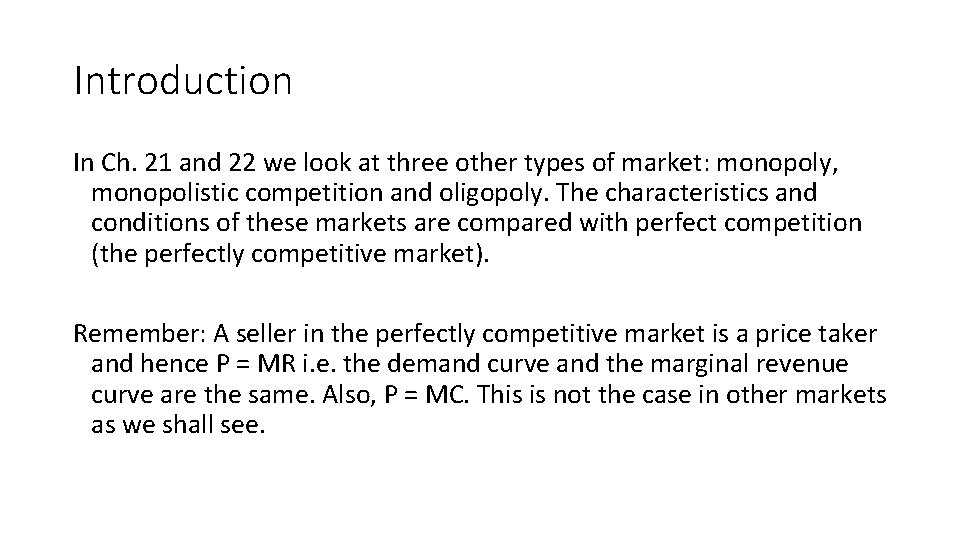

Market Characteristics Monopoly (E. g. Water Supply Industry, Electricity Supply Industry, Railway Service) • Single seller (the monopolist) e. g. WASA, DESCO, Bangladesh Railway • The single seller sells a product for which there are no close substitutes • High barriers to entry Monopolistic Competition [E. g. Fast food Market, Hairdressing Market, Coaching Centres (Private Tuition Market)] Oligopoly (E. g. Telecommunication Industry, Aviation Industry) • There are many sellers and buyers • Each firm produces and sells a slightly differentiated product • There is easy entry and exit • Few sellers and many buyers • Firms producing either homogenous or differentiated products • Significant barriers to entry

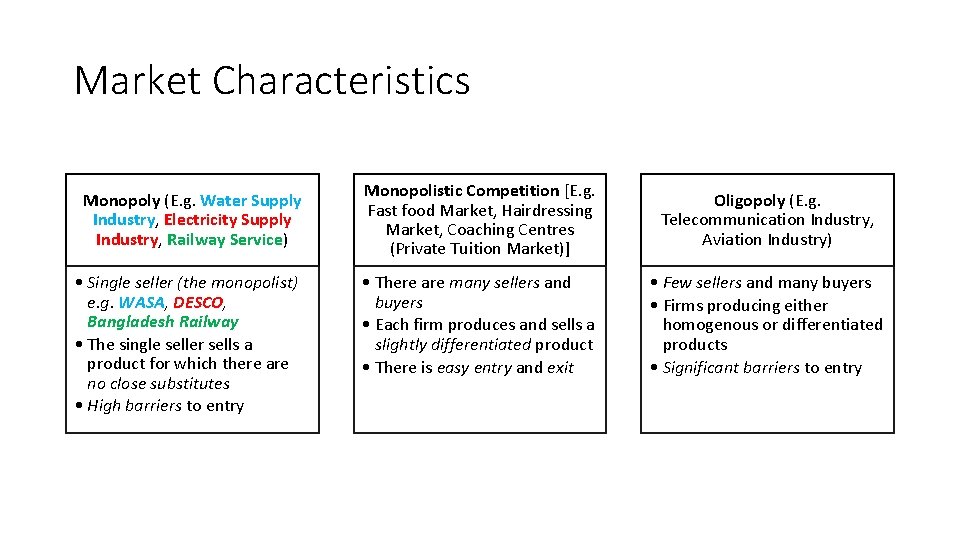

Pricing (P) and Output (Q) Decisions Monopoly • Price searcher (a seller that has the ability to control to some degree the price of the product it sells) • P > MR • Produces Q at which MR = MC • Hence, P > MC Monopolistic Competition • Price searcher • P > MR • Produces Q at which MR = MC • Hence, P > MC Oligopoly • Price searcher • P > MR • Produces Q at which MR = MC • Hence, P > MC

Monopoly: Barriers to Entry In the next few slides we discuss the Monopoly Market (e. g. railway service and water supply markets - each has one seller - Bangladesh Railway and WASA respectively) In a monopoly market it is (almost) impossible for new sellers to enter the market or industry i. e. there are extremely high barriers to entry. Why? 1) Government Rules and Regulations: (Patents & Copyrights or Government Licence & Permission given to only one seller. These rules and restrictions prevent new sellers from entering the market) Why does the government give license or permission to only one firm or factory? Answer: Sometimes only one large firm or factory can produce a good or service most efficiently – least wastage and lowest ATC (cost per unit). If this is the case, then the firm is called a natural monopoly (e. g. WASA, Bangladesh Railway).

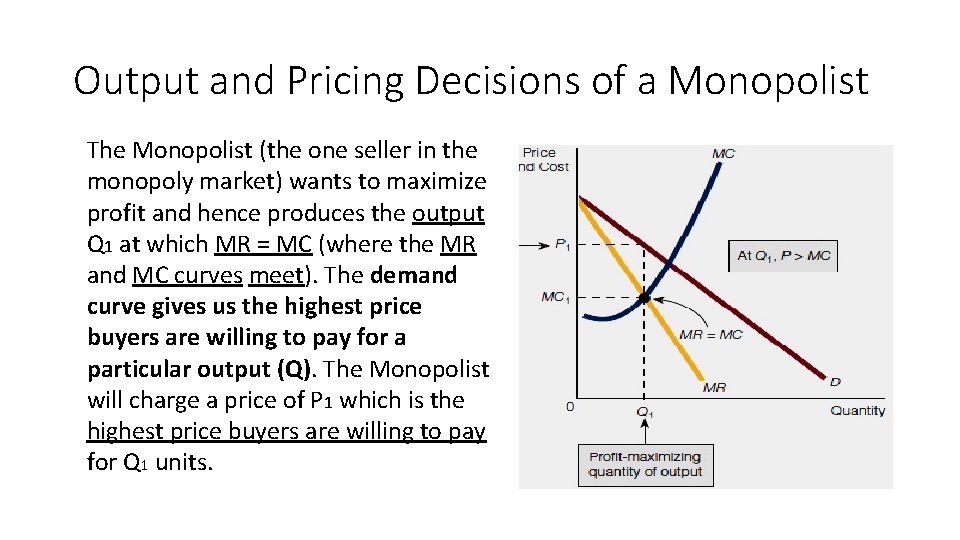

Output and Pricing Decisions of a Monopolist The Monopolist (the one seller in the monopoly market) wants to maximize profit and hence produces the output Q 1 at which MR = MC (where the MR and MC curves meet). The demand curve gives us the highest price buyers are willing to pay for a particular output (Q). The Monopolist will charge a price of P 1 which is the highest price buyers are willing to pay for Q 1 units.

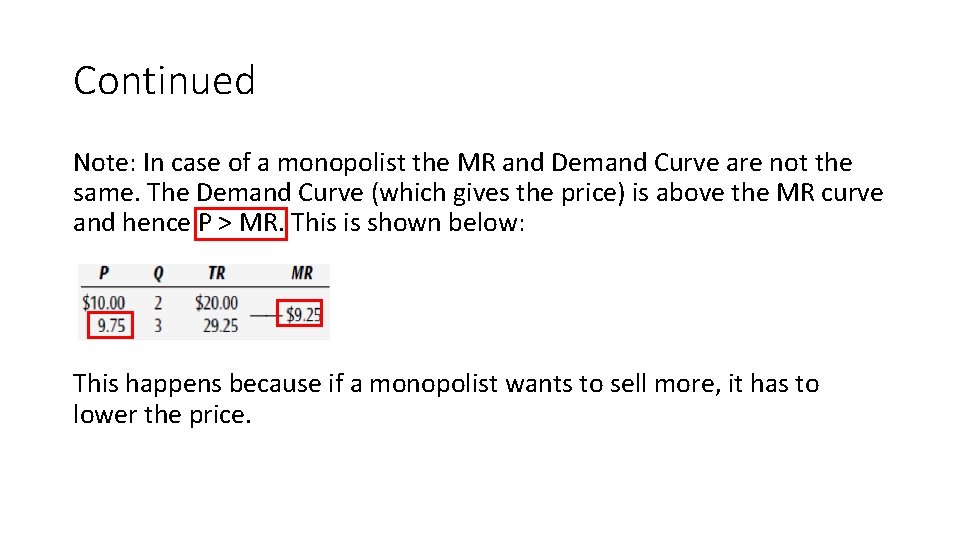

Continued Note: In case of a monopolist the MR and Demand Curve are not the same. The Demand Curve (which gives the price) is above the MR curve and hence P > MR. This is shown below: This happens because if a monopolist wants to sell more, it has to lower the price.

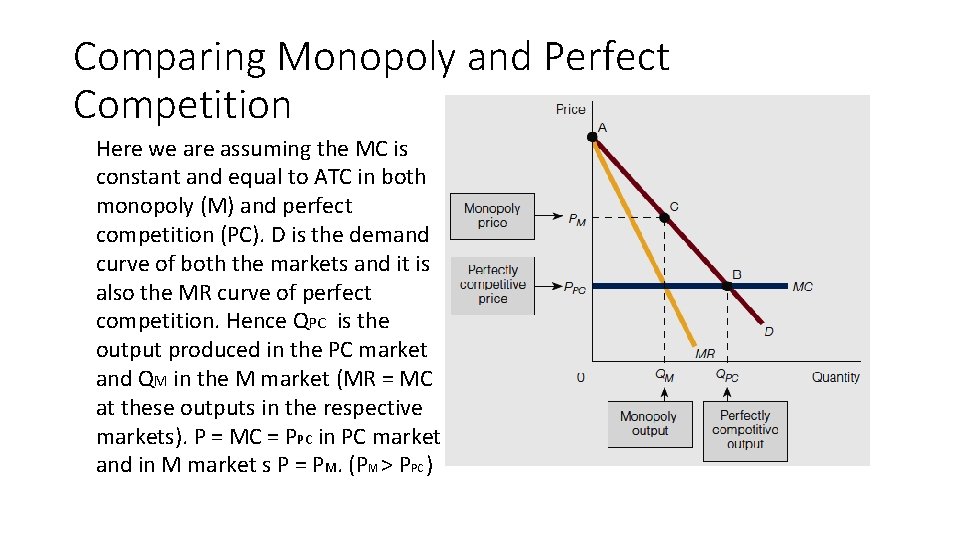

Comparing Monopoly and Perfect Competition Here we are assuming the MC is constant and equal to ATC in both monopoly (M) and perfect competition (PC). D is the demand curve of both the markets and it is also the MR curve of perfect competition. Hence QPC is the output produced in the PC market and QM in the M market (MR = MC at these outputs in the respective markets). P = MC = PPC in PC market and in M market s P = PM. (PM > PPC )

Continued At the end of last slide, we can see the perfectly competitive (PC) market produces more output and sells them at a lower price as compared to a monopoly market. Does it make rational sense? When there are many sellers and easy entry, there will be more competition, less price, more efficiency and more output. In the next two slides, we compare the benefit (welfare) of buyers, sellers and the overall society from the two different markets: monopoly and perfect competition.

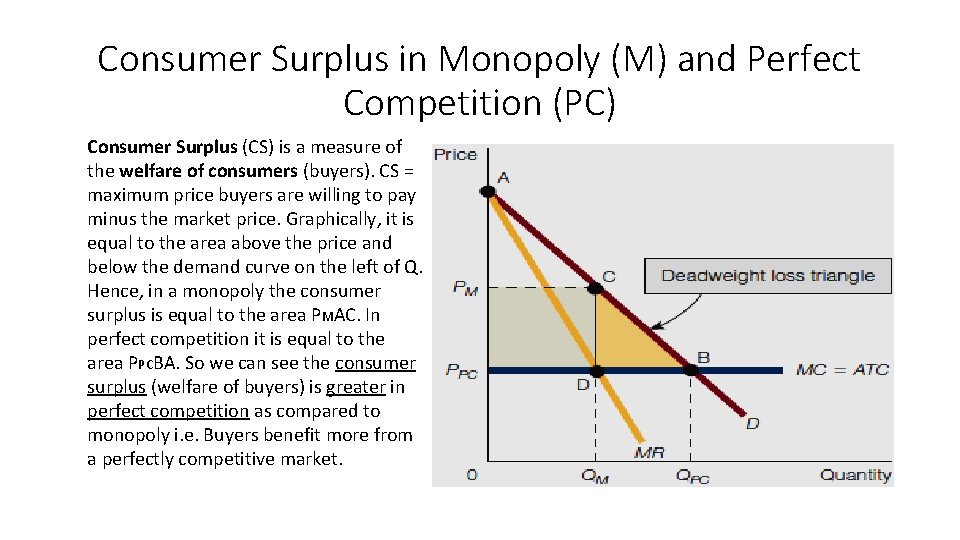

Consumer Surplus in Monopoly (M) and Perfect Competition (PC) Consumer Surplus (CS) is a measure of the welfare of consumers (buyers). CS = maximum price buyers are willing to pay minus the market price. Graphically, it is equal to the area above the price and below the demand curve on the left of Q. Hence, in a monopoly the consumer surplus is equal to the area PMAC. In perfect competition it is equal to the area PPCBA. So we can see the consumer surplus (welfare of buyers) is greater in perfect competition as compared to monopoly i. e. Buyers benefit more from a perfectly competitive market.

Comparing Producer Surpluses The producer surplus may also be measured from the figure (last slide). Producer Surplus = price received minus the minimum price at which the producer is willing to sell, it is a measure of the welfare of producers (sellers) in a market. Graphically, it is equal to the area below the price and above the ATC curve here on the left of Q. Hence, it is zero in perfect competition and it is equal to the area PPCDCPM in monopoly. Total Surplus (a measure of the welfare of society) = Consumer Surplus + Producer Surplus. As we can see total surplus in Monopoly (M) < total surplus of Perfect Competition (PC). The Deadweight Loss is given by the area DBC and is equal to total surplus of PC market minus total surplus of M market. It is a measure of the loss which the entire society incurs due to the monopoly output.

![Monopolistic Competition [E. g. Fast Food Market, Street Food Market, Hairdressing (Barber Shops) Market] Monopolistic Competition [E. g. Fast Food Market, Street Food Market, Hairdressing (Barber Shops) Market]](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/7a78f54c5e75ffed0ac1098dbc9063f2/image-12.jpg)

Monopolistic Competition [E. g. Fast Food Market, Street Food Market, Hairdressing (Barber Shops) Market] Since in this market the sellers are selling slightly differentiated products (e. g. coke and pepsi), the sellers in this market are price searchers. They can control the price to some extent (e. g. coke may increase the price and even then some people will still buy coke since it is slightly different from other soft-drinks). If a seller is price searcher, then this implies P > MR. In the long run, this market tends to approach zero economic profit (i. e. P = ATC) because of easy entry. E. g. if the sellers enjoy positive economic profit (P > ATC) then this attracts new sellers (supply increases) and the price falls until zero economic profit (P = ATC).

Oligopoly and The Cartel Theory There a few sellers in an Oligopoly Market (e. g. in the ride-sharing industry, the sellers are: Uber, Pathao, Shohoj, OBHAI). It is possible that these few sellers may form a cartel (similar to a syndicate). A cartel is a group of sellers that reduce (market) output and increase (market) price to increase joint profits. E. g. This usually happens in Bangladesh during Ramadan (food price increases because suppliers reduce supply). Firms may benefit from cartel formation (more profit). But consumers will suffer (more price, less output). Hence, the government may ban cartel formation in certain industries.

Price Discrimination refers to the practice of selling the same product (or service) at different prices to different customers. E. g. a CNG may charge a student lower price and an office-goer a higher price. If a seller has some market power (selling a differentiated product and / or there few other sellers), then a seller can price-discriminate. Types of price discrimination: 1) Perfect (first degree) price discrimination: The seller charges every buyer the maximum price (s)he is willing to pay. 2) Second degree price discrimination: Dividing the output into different blocks (groups) and then selling them at different prices. E. g. a seller may sell the first 10 units at $15 each and the next 5 units at $5 each. 3) Third degree price discrimination: Dividing the buyers into segments and then charging each segment a different price. E. g. students pay a lower fare in public buses.

Analyzing Production in the Short-Run Remember in the short-run there is a fixed cost (e. g. the rent of a leased factory or shop) which does not vary with output. No matter what a business decides (to produce), it will not affect the fixed cost. A cost that is not affected (or cannot be recovered) by current decisions is called a sunk cost. Therefore, in the short-run, the fixed cost is the sunk cost. Since, fixed cost is not affected by current decisions (in the short-run), it should not be considered when making decisions in the short-run (according to microeconomic theory). Only the variable cost needs to be considered in the short-run: if P (price per unit) > Variable Cost per unit (average variable cost, AVC) , then the business should continue production.

Continued So according to microeconomic theory, we will continue production in the short run if P > AVC. Let’s see the logic (rationality) behind it: E. g. fixed cost = $ 400 , Variable cost = $ 300, Q = 60 units, P = $ 10. Revenue = $ 10(60) = $ 600. Therefore, profit = revenue – cost = 600 – (400 + 300) = - 100. So the business is incurring a loss of $ 100. Should the business stop production? If it stops production, then it has to pay the fixed cost of $ 400 (a loss of $ 400). If it continues production, then the loss is only $ 100. Therefore, the business minimizes the loss by continuing production in the short-run. Here, AVC = (300 ÷ 60 ) = 5. Therefore, P > AVC and the business continues production.

Conclusion Remember: microeconomics is the science of decision-making or choice. According to microeconomics, when making a decision or choice we should ignore those factors that will not be affected by our decision or choice (e. g. sunk costs). Also, we should consider opportunity costs. These may lead to better decisions and choices. E. g. you go to a movie and then lose the ticket. When thinking whether to buy another ticket, you should not consider (the price of) the lost ticket (sunk cost). According to microeconomics - you should only focus on the benefit and opportunity cost of the next (marginal) ticket.

- Slides: 17