Locke and Natural Kinds PHIL 2130 What is

- Slides: 19

Locke and Natural Kinds PHIL 2130

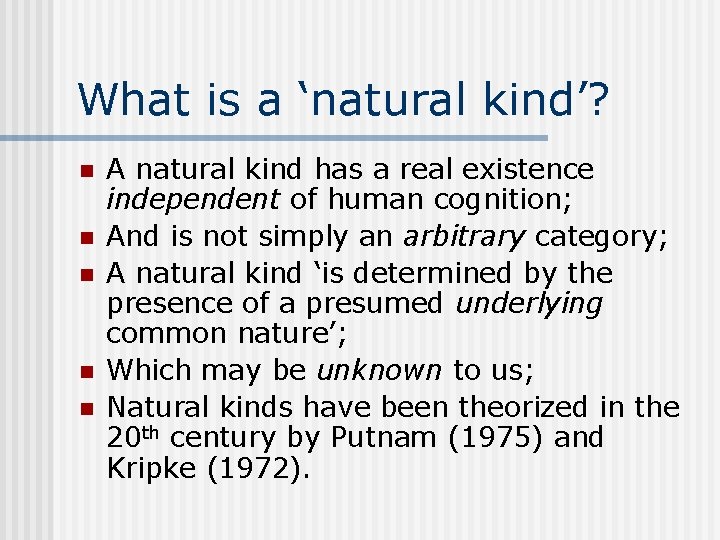

What is a ‘natural kind’? n n n A natural kind has a real existence independent of human cognition; And is not simply an arbitrary category; A natural kind ‘is determined by the presence of a presumed underlying common nature’; Which may be unknown to us; Natural kinds have been theorized in the 20 th century by Putnam (1975) and Kripke (1972).

Examples of ‘natural kinds’:

Why are they different? n n n They obviously look different, but what factors are you going to say make them essentially different? morphological (form), phylogenetic (race history) or reproductive factors? There are lively debates in biology and philosophy about what factors determine membership of a kind (species or genus).

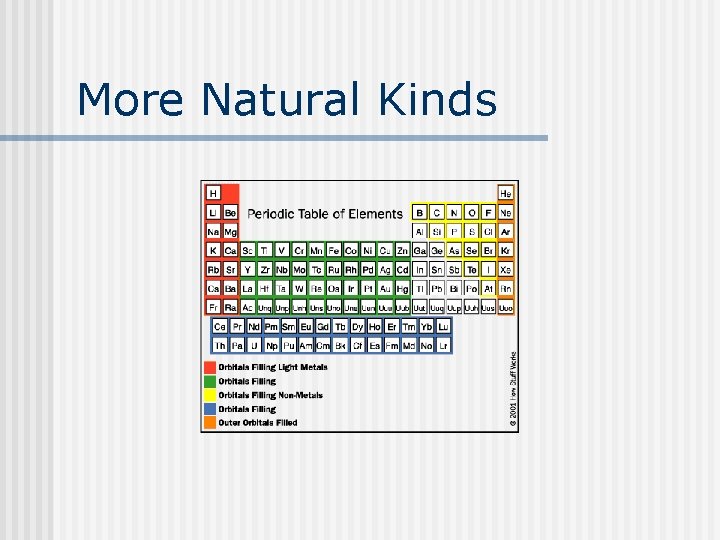

More Natural Kinds

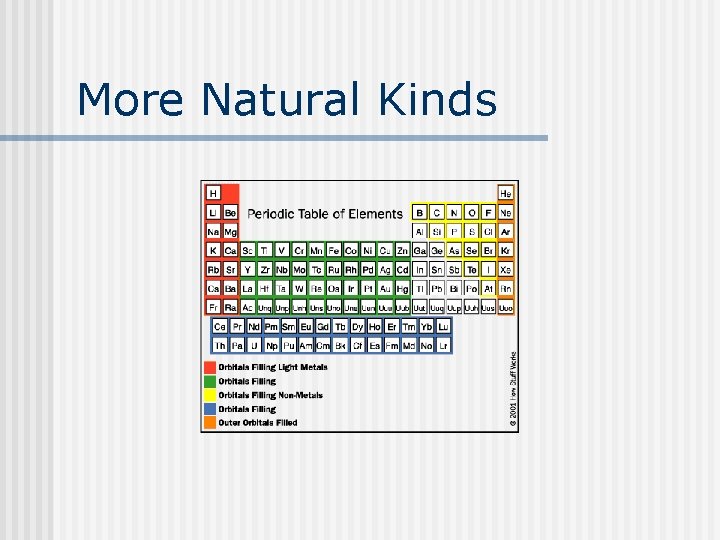

Periodic Table n n n The atomic number of a given element is taken to be (at least) one good possibility for the real essence of an element; Can you think of any other possibilities? What is real essence? Real essence is the underlying characteristic that defines a natural kind, as contrasted with nominal essences that are superficial, possibly even irrelevant; Essentialism is the philosophical position that holds that kinds have essences.

How can natural kinds be unknown to us? n n n We may recognize the external appearance of a thing or substance and assume it belongs to a particular kind; But we may be mistaken, as Putnam argues in his water on Mars example; There could be a substance on Mars that appears in every respect to resemble water, but for one very important reason does not: it does not possess the underlying chemical structure H 2 O.

What’s at stake? Philosophers since Aristotle (384 -322 BCE) have studied the relation between words and things; n Aristotle developed an elaborate account of the categories of being, definition and predication; n Locke continues this analysis, but rejects many of Aristotle’s ideas, e. g. rules of definition (III, iii, ¶ 10, 15); n The ultimate goal for many students of this problem, including Locke (the scientist), is a classification of nature.

What is classification? n n n Classification organizes things, substances or anything else you can think of into categories According to some criterion (sing. ) or criteria (pl. ) So you may classify your stationary kit by separating pens by color, pencils by presence /absence of erasers, etc. Try this and see how many different categories of classification you can develop for the same set of items! This will give you an idea of what a complex task it is; Biologists may categorize by presence/absence of a particular gene, a particular external feature (sheep have curly wool, while horses don’t).

Why is classification important? n n n Classification enables us to organize our knowledge about the world; How? By creating groups of things to which we can assign names; Why are names important? Because they enable us not only to retain the category in our minds, But also to communicate with others about things in the world.

Imagine a different world Where there are names only of particular things: this horse, that sheep, but not horse in general or sheep in general; n So each sheep and horse would need its own particular name; how could we study sheep or horse characteristics—eating habits, mating, or genetics—on this basis? n

Too many names Locke’s answers: “it is beyond the Power of humane Capacity to frame and retain distinct Ideas of all the particular Things we meet with: every Bird, and Beast Men saw; every Tree, and Plant, that affected the Senses, could not find a place in even the most capacious [large] Understanding” (III, iii, ¶ 2). n

Particular Names not useful n “If it were possible, it would yet be useless; because it would not serve to the chief end of Language. Men would in vain heap up Names of particular Things, that would not serve them to communicate their Thoughts. Men learn Names, and use them in Talk with others, only that they may be understood…the sound I make…excites in another Man’s Mind…the Idea I apply it to in mine” (III, iii, ¶ 3).

Knowledge is founded on Generalities n “…a distinct Name for every particular Thing, would not be of any great use for the improvement of Knowledge: which though founded in particular Things, enlarges it self by general Views; to which, Things reduced into sorts [categories] under general Names, are properly subservient [subordinate]” (III, iii, ¶ 4).

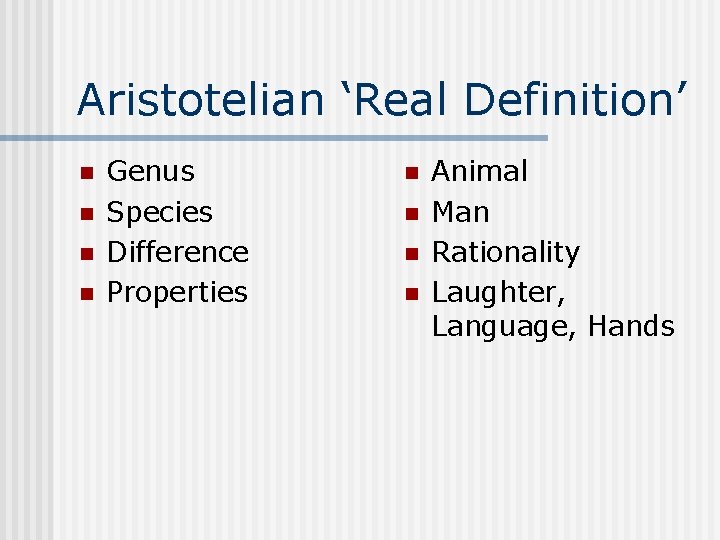

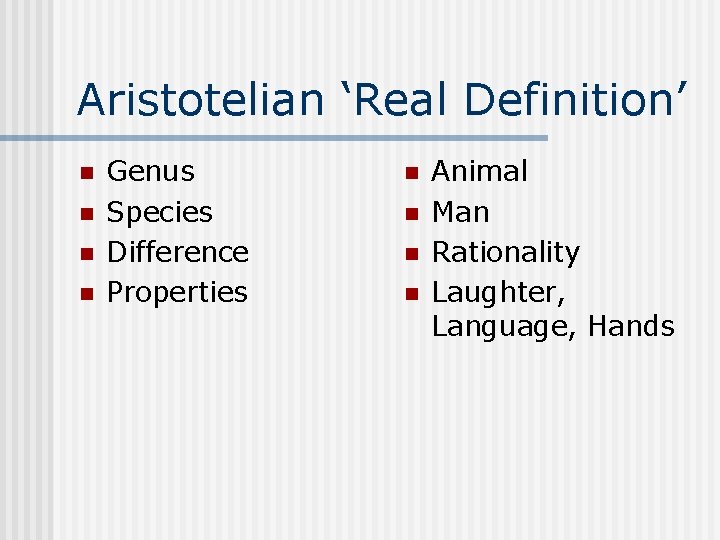

Aristotelian ‘Real Definition’ n n Genus Species Difference Properties n n Animal Man Rationality Laughter, Language, Hands

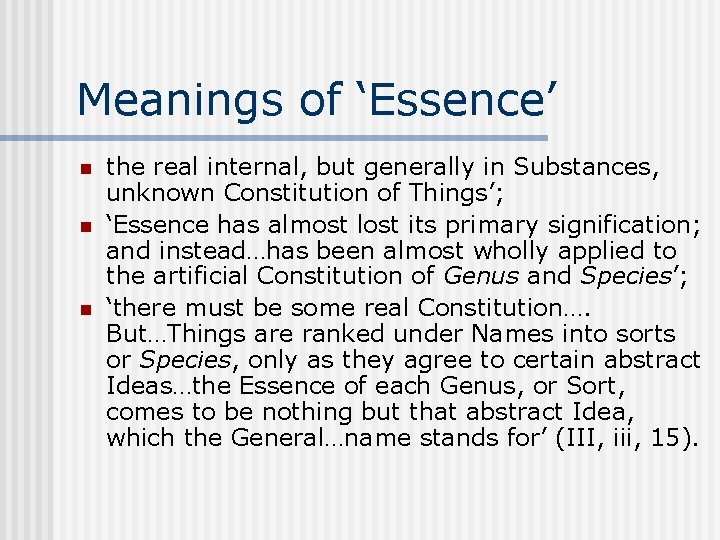

Meanings of ‘Essence’ n n n the real internal, but generally in Substances, unknown Constitution of Things’; ‘Essence has almost lost its primary signification; and instead…has been almost wholly applied to the artificial Constitution of Genus and Species’; ‘there must be some real Constitution…. But…Things are ranked under Names into sorts or Species, only as they agree to certain abstract Ideas…the Essence of each Genus, or Sort, comes to be nothing but that abstract Idea, which the General…name stands for’ (III, iii, 15).

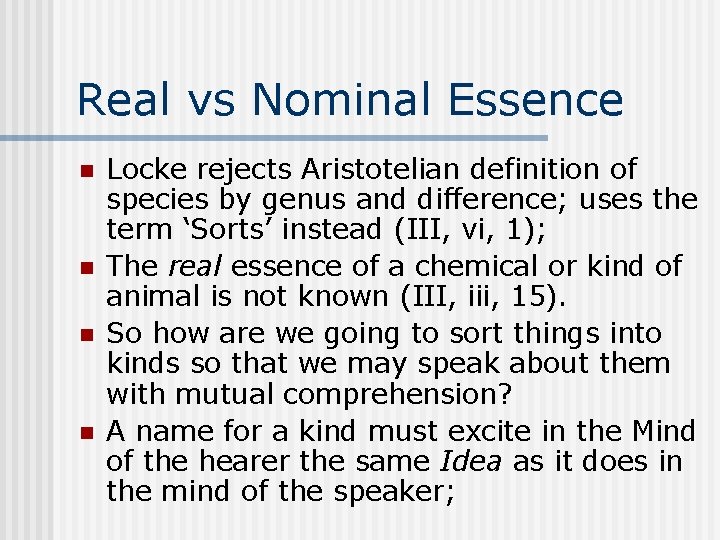

Real vs Nominal Essence n n Locke rejects Aristotelian definition of species by genus and difference; uses the term ‘Sorts’ instead (III, vi, 1); The real essence of a chemical or kind of animal is not known (III, iii, 15). So how are we going to sort things into kinds so that we may speak about them with mutual comprehension? A name for a kind must excite in the Mind of the hearer the same Idea as it does in the mind of the speaker;

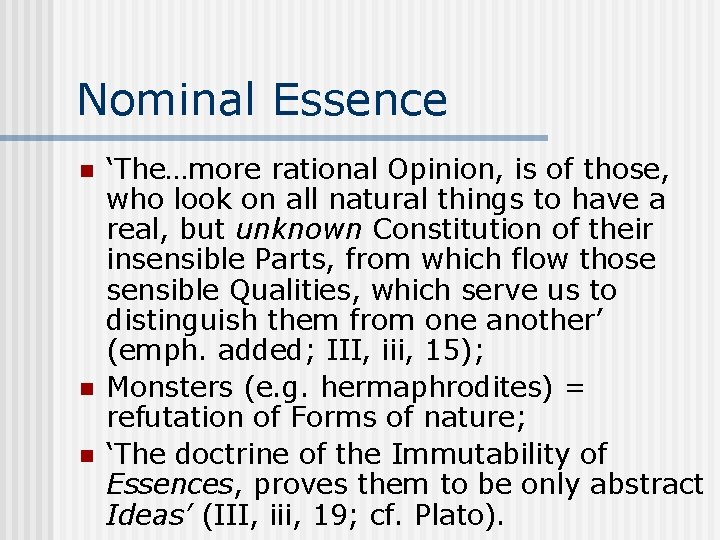

Nominal Essence n n n ‘The…more rational Opinion, is of those, who look on all natural things to have a real, but unknown Constitution of their insensible Parts, from which flow those sensible Qualities, which serve us to distinguish them from one another’ (emph. added; III, iii, 15); Monsters (e. g. hermaphrodites) = refutation of Forms of nature; ‘The doctrine of the Immutability of Essences, proves them to be only abstract Ideas’ (III, iii, 19; cf. Plato).

To be continued… n n n Is Locke an essentialist? See Essay, Book III, chs. 3 and 6. Note that when Locke refers to ‘the Schools’ he is referring to the Aristotelian logic and philosophy of language taught in the medieval and early-modern European universities. Further reading: Ernst Mayr, “Species Concepts and Their Application” (Dept. ). Try a classification exercise!

Comp 2130

Comp 2130 Cs 2130

Cs 2130 Jean jacques rousseau estado de naturaleza

Jean jacques rousseau estado de naturaleza Lei natural locke

Lei natural locke Aristotle virtue ethics

Aristotle virtue ethics Phil and cath make and sell boomerangs

Phil and cath make and sell boomerangs Natural capital

Natural capital Giving and receiving feedback by phil rich

Giving and receiving feedback by phil rich Swot analysis of goldstar shoes

Swot analysis of goldstar shoes Natural hazards vs natural disasters

Natural hazards vs natural disasters Hobbes and locke venn diagram

Hobbes and locke venn diagram Voltaire john locke

Voltaire john locke Patiarcha

Patiarcha Goal setting theory of motivation

Goal setting theory of motivation John locke vs thomas hobbes

John locke vs thomas hobbes Locke berkeley and hume

Locke berkeley and hume Hobbes and locke venn diagram

Hobbes and locke venn diagram Scientific revolution and enlightenment speed dating

Scientific revolution and enlightenment speed dating Locke and key art

Locke and key art Locke idealism

Locke idealism