James Kelman and Liz Lochhead Dr Scott Lyall

- Slides: 24

James Kelman and Liz Lochhead Dr Scott Lyall Edinburgh Napier University s. lyall@napier. ac. uk

Context • Twentieth-century Scottish Literature – two main literary movements: • the 1920 s (ruralist) and 1980 s (urban) • Scottish Renaissance Movement • Kailyard literature • The significance of 1979 2

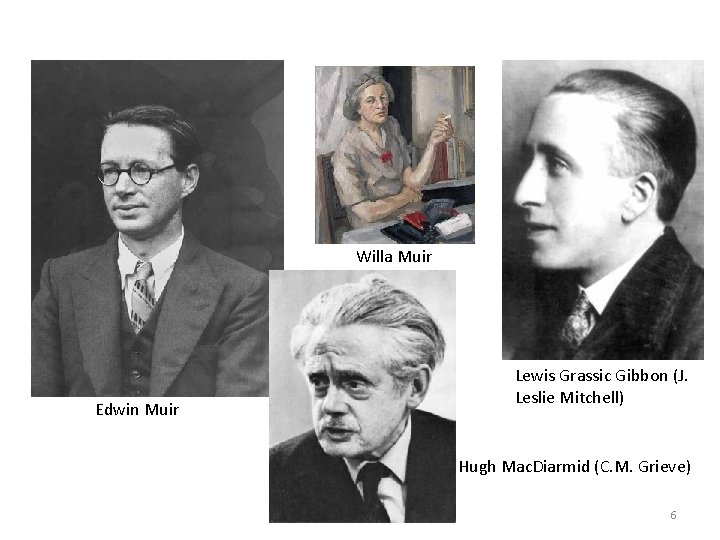

Scottish Renaissance Movement (c. 1920 s – 1940 s) – Interwar movement prompted by WW 1 – inspired by Irish Literary Revival and Easter 1916 – seeking an internationalist Scottish, post-British voice in all the arts – opposed to the provincialisation of Scotland through the ‘Kailyard’ in Scottish literature – yet, Hugh Mac. Diarmid, Lewis Grassic Gibbon, Edwin and Willa Muir, Neil M. Gunn, Nan Shepherd, all from small town birthplaces 3

Kailyard literature – ‘cabbage-patch’ – small-town Scotland; anti-industrial; Christian; implicitly Presbyterian – J. M. Barrie (1860 -1937): Auld Licht Idylls (1888); A Window in Thrums (1889) – S. R. Crockett; Ian Maclaren (Free Church of Scotland ministers) – ‘lad o’pairts’ – anti-Kailyard novel: George Douglas Brown, The House with the Green Shutters (1901) 4

Hostility of Scottish Renaissance Movement to urban landscape – Hugh Mac. Diarmid (1892 -1978), Lucky Poet (1943): ‘I do not like Edinburgh (or any city very much), for I have never been able to find one that was not full of reminders of the fact that Cain, the murderer, was also the first city-builder. ’ (105) – Lewis Grassic Gibbon (1901 -35), A Scots Quair (1946): Sunset Song (1932), Cloud Howe (1933), Grey Granite (1934) – from farm, to town, to city – Edwin Muir (1887 -1959), One Foot in Eden (1956); Orkney (Christian) Eden; Glasgow = hell 5

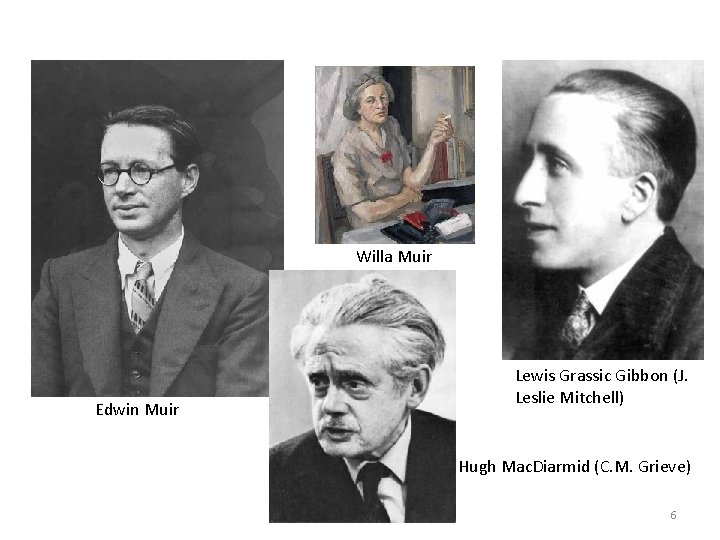

Willa Muir Edwin Muir Lewis Grassic Gibbon (J. Leslie Mitchell) Hugh Mac. Diarmid (C. M. Grieve) 6

The 1980 s: 1979 and all that – as significant to modern Scottish literature as the 1920 s – tended to have an urban focus – a form of national crisis was in some measure behind the cultural boom of the 80 s: a representational crisis • 1979: failed Devolution Referendum – seminal post-1979 text: Alasdair Gray, Lanark (1981) – ‘Glasgow Mafia’: James Kelman, Alasdair Gray, Tom Leonard, Liz Lochhead, Jeff Torrington – influential to younger writers such as Irvine Welsh, Alan Warner, Laura Hird, A. L. Kennedy 7

James Kelman Tom Leonard William Mc. Ilvanney Liz Lochhead Alasdair Gray 8

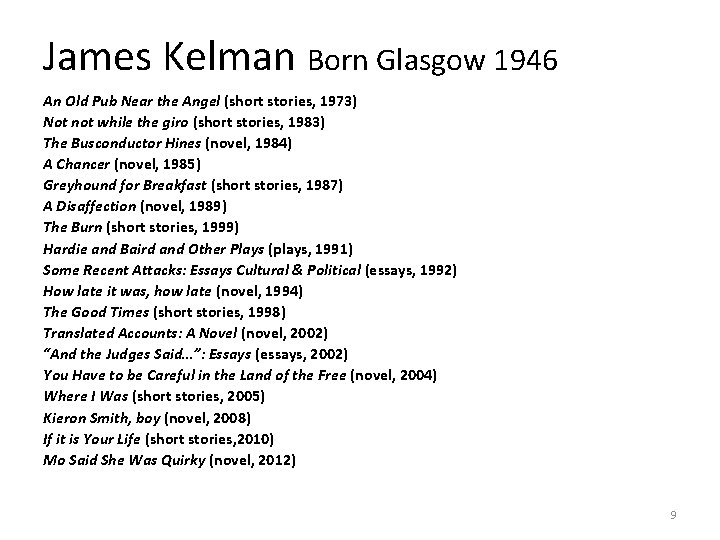

James Kelman Born Glasgow 1946 An Old Pub Near the Angel (short stories, 1973) Not not while the giro (short stories, 1983) The Busconductor Hines (novel, 1984) A Chancer (novel, 1985) Greyhound for Breakfast (short stories, 1987) A Disaffection (novel, 1989) The Burn (short stories, 1999) Hardie and Baird and Other Plays (plays, 1991) Some Recent Attacks: Essays Cultural & Political (essays, 1992) How late it was, how late (novel, 1994) The Good Times (short stories, 1998) Translated Accounts: A Novel (novel, 2002) “And the Judges Said…”: Essays (essays, 2002) You Have to be Careful in the Land of the Free (novel, 2004) Where I Was (short stories, 2005) Kieron Smith, boy (novel, 2008) If it is Your Life (short stories, 2010) Mo Said She Was Quirky (novel, 2012) 9

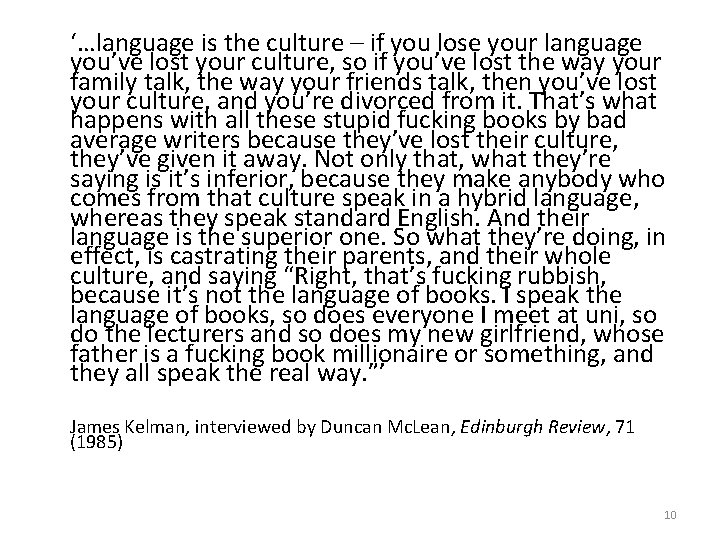

‘…language is the culture – if you lose your language you’ve lost your culture, so if you’ve lost the way your family talk, the way your friends talk, then you’ve lost your culture, and you’re divorced from it. That’s what happens with all these stupid fucking books by bad average writers because they’ve lost their culture, they’ve given it away. Not only that, what they’re saying is it’s inferior, because they make anybody who comes from that culture speak in a hybrid language, whereas they speak standard English. And their language is the superior one. So what they’re doing, in effect, is castrating their parents, and their whole culture, and saying “Right, that’s fucking rubbish, because it’s not the language of books. I speak the language of books, so does everyone I meet at uni, so do the lecturers and so does my new girlfriend, whose father is a fucking book millionaire or something, and they all speak the real way. ”’ James Kelman, interviewed by Duncan Mc. Lean, Edinburgh Review, 71 (1985) 10

‘My own background is as normal or abnormal as anyone else’s. Born and bred in Govan and Drumchapel, inner city tenement to the housing scheme homeland on the outer reaches of the city. Four brothers, my mother a full-time parent, my father in the picture framemaking and gilding trade, trying to operate a one-man business. And I left school at 15 etc. The kind of working-class background that can include relatives who have white collar occupations – even distant relatives who were “school teachers”. Books were not unknown in my home and social mobility certainly existed as a concept. For some reason or another, by the age of 21 / 22 I decided to write stories. The stories I wanted to write would derive from my own background, my own sociocultural experience. I wanted to write as one of my own people, I wanted to write and remain a member of my community. ’ James Kelman, ‘The Importance of Glasgow in My Work’, Some Recent Attacks (Stirling: AK Press, 1992), p. 81. 11

‘The English literature I had access to through the normal channels is what you might call stateeducation-system-influenced reading material. People from communities like mine were rarely to be found on these pages. When they were usually categorised as servants, peasants, criminal elements, semi-literate drunken louts, and so on; shadowy presences left unspecified, often grouped under items like “uncouth rabble”, “vulgar mob”, “the great unwashed”; “lumpen proletariat”, even “riotous assembly” (an obscure hint that political activism by these lower-order beings was not unheard of). ’ James Kelman, ‘And the judges said…’, ‘And the Judges Said’: Essays (London: Secker & Warburg, 2002), p. 38. 12

The Glasgow novel • No Mean City (1935) by Mc. Arthur and Long: bestseller about razor gangs in Glasgow • Wee Macgreegor stories by J. J. Bell • Archie Hind, The Dear Green Place (1966) • William Mc. Ilvanney, Docherty (1975) • Alasdair Gray, Lanark: A Life in 4 Books (1981) 13

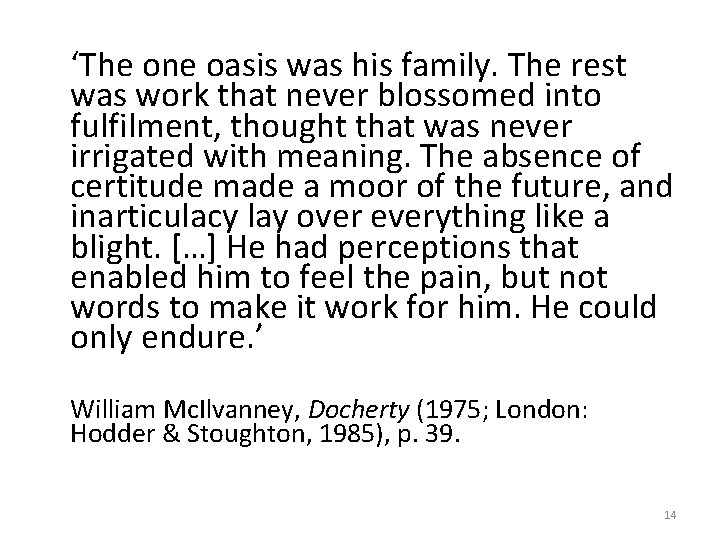

‘The one oasis was his family. The rest was work that never blossomed into fulfilment, thought that was never irrigated with meaning. The absence of certitude made a moor of the future, and inarticulacy lay over everything like a blight. […] He had perceptions that enabled him to feel the pain, but not words to make it work for him. He could only endure. ’ William Mc. Ilvanney, Docherty (1975; London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1985), p. 39. 14

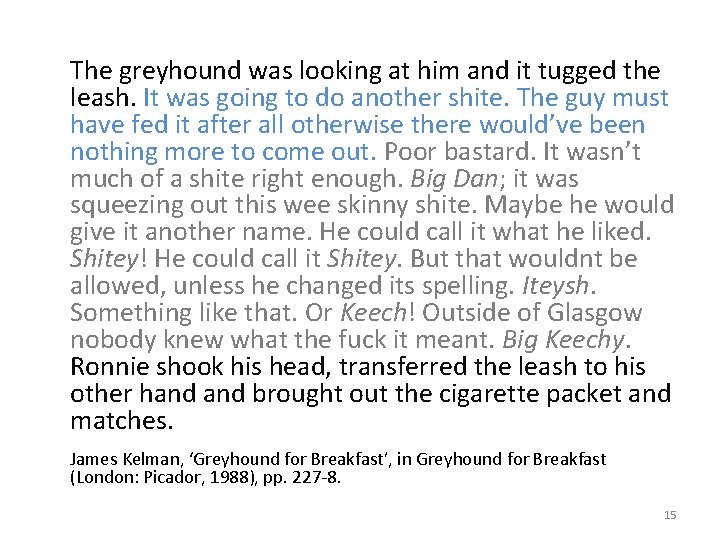

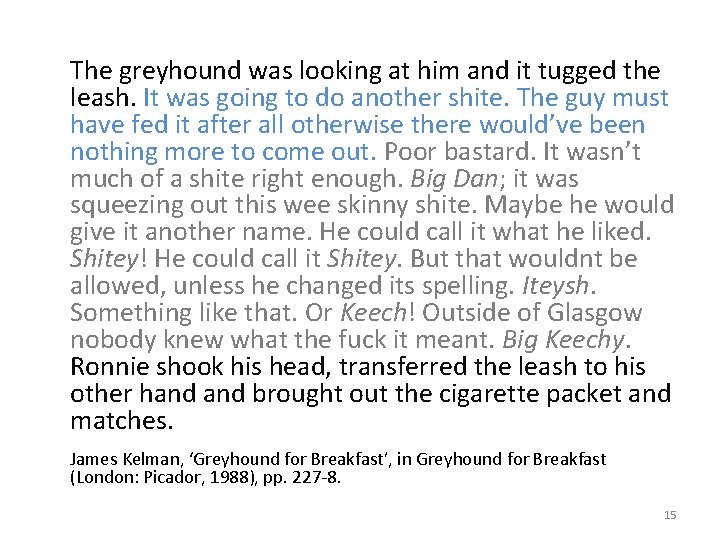

The greyhound was looking at him and it tugged the leash. It was going to do another shite. The guy must have fed it after all otherwise there would’ve been nothing more to come out. Poor bastard. It wasn’t much of a shite right enough. Big Dan; it was squeezing out this wee skinny shite. Maybe he would give it another name. He could call it what he liked. Shitey! He could call it Shitey. But that wouldnt be allowed, unless he changed its spelling. Iteysh. Something like that. Or Keech! Outside of Glasgow nobody knew what the fuck it meant. Big Keechy. Ronnie shook his head, transferred the leash to his other hand brought out the cigarette packet and matches. James Kelman, ‘Greyhound for Breakfast’, in Greyhound for Breakfast (London: Picador, 1988), pp. 227 -8. 15

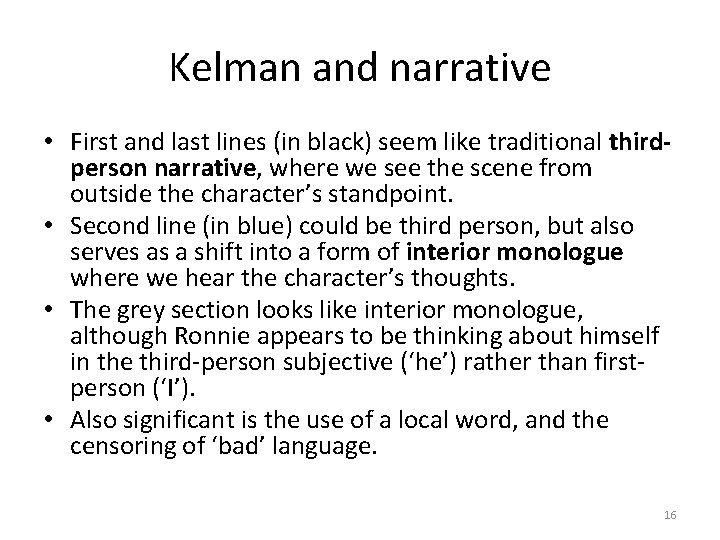

Kelman and narrative • First and last lines (in black) seem like traditional thirdperson narrative, where we see the scene from outside the character’s standpoint. • Second line (in blue) could be third person, but also serves as a shift into a form of interior monologue where we hear the character’s thoughts. • The grey section looks like interior monologue, although Ronnie appears to be thinking about himself in the third-person subjective (‘he’) rather than firstperson (‘I’). • Also significant is the use of a local word, and the censoring of ‘bad’ language. 16

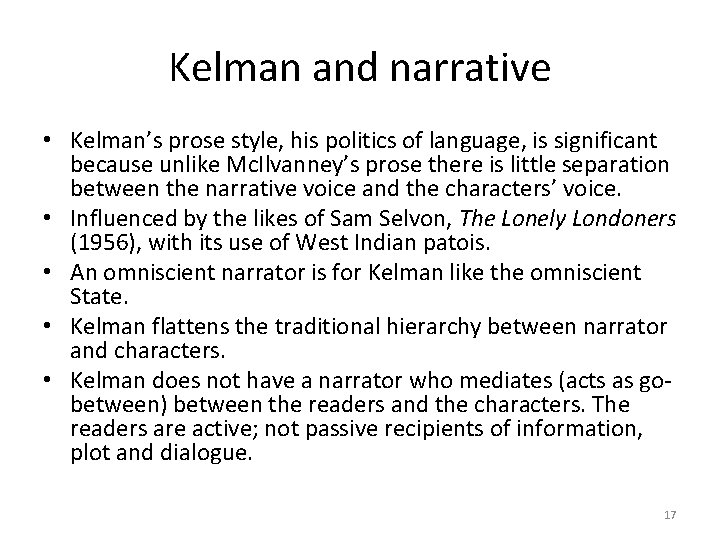

Kelman and narrative • Kelman’s prose style, his politics of language, is significant because unlike Mc. Ilvanney’s prose there is little separation between the narrative voice and the characters’ voice. • Influenced by the likes of Sam Selvon, The Lonely Londoners (1956), with its use of West Indian patois. • An omniscient narrator is for Kelman like the omniscient State. • Kelman flattens the traditional hierarchy between narrator and characters. • Kelman does not have a narrator who mediates (acts as gobetween) between the readers and the characters. The readers are active; not passive recipients of information, plot and dialogue. 17

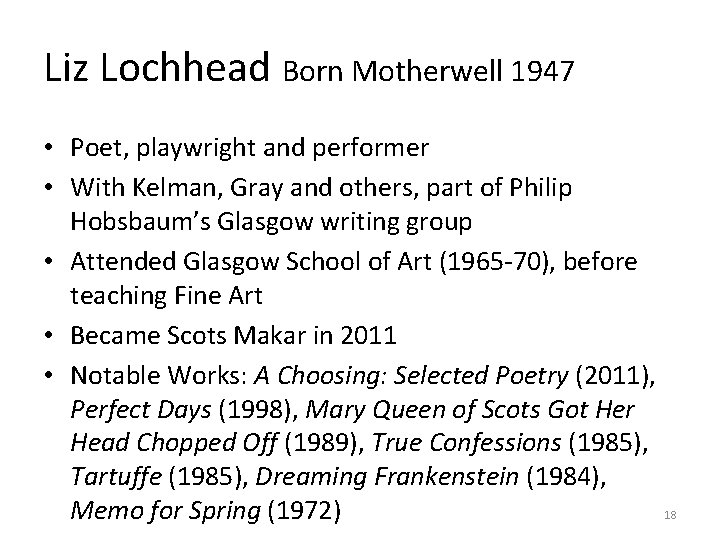

Liz Lochhead Born Motherwell 1947 • Poet, playwright and performer • With Kelman, Gray and others, part of Philip Hobsbaum’s Glasgow writing group • Attended Glasgow School of Art (1965 -70), before teaching Fine Art • Became Scots Makar in 2011 • Notable Works: A Choosing: Selected Poetry (2011), Perfect Days (1998), Mary Queen of Scots Got Her Head Chopped Off (1989), True Confessions (1985), Tartuffe (1985), Dreaming Frankenstein (1984), Memo for Spring (1972) 18

Mary, Queen of Scots • • • Mary Stuart (or Stewart), born 1542. Daughter of James V, and came to the throne at 6 days old when he died. Spent childhood in France, married Dauphin of France, but widowed. The Catholic Mary returned to Scotland in 1561, during the Protestant Reformation of John Knox and the Reformers. Married Lord Darnley, who was implicated in the murder of her secretary, Riccio. Darnley himself murdered, with the Earl of Bothwell probably involved. Mary marries Bothwell, bringing opposition from Scottish nobles. Mary flees to England for protection from Queen Elizabeth I (her first cousin removed). Seen by English Catholics as the rightful monarch, Mary is imprisoned by Elizabeth for almost two decades, before being executed in 1587. 19

Mary Queen of Scots Got Her Head Chopped Off • Commissioned by Communicado Theatre Group for the 400 th anniversary of the death of Mary, Queen of Scots. • First performed at the Lyceum, Edinburgh Festival Fringe in 1987. • Published by Penguin in 1989. • Lochhead called the play ‘a metaphor for the Scots today’. – What does she mean by this? – And is this ‘metaphor’ still relevant today? 20

‘Scotland, Whit Like? ’ • Questions the myth-history of Scotland. • Asks, how does our past inform our present, and what is the relationship between national myth-history and contemporary Scotland? • Two key issues for Lochhead: the Reformation and modern sectarianism; and the place of women on modern Scottish society – she uses Mary and the cast of characters to explore both of these. 21

Opposites • Opposites in the play: Mary and Elizabeth; Knox and Mary; Knox and Bothwell, etc. • Illustrates a Scotland (and a Britain) that is polarised along religious lines – Catholic / Protestant – and gender lines. • Knox is shown as a present-day Orangeman (Act 1, scene 4): bigoted, misogynistic, sexually-repressed. • Elizabeth is shown to be consumed by power to the exclusion of her female side; in the 1980 s, this may have reminded some of Margaret Thatcher. 22

Language and Style • Employs different language registers illustrating class and nation: Elizabeth and the Anglifier Knox, often more formal; Mary and Bothwell more ‘Scottish’. • Plays on the Scottish Renaissance Movement idea that the Reformation killed the arts and theatre in Scotland; feeling/life still with Catholic (female) pre. Union Scotland. • Use of Scots most prominent in La Corbie (the crow), symbolising the Scots’ reductive wit. • By mingling the past and the present, ‘makes strange’ both eras and forces us to question them. 23

‘Jock Thamson’s Bairns’ • How do we read the meaning of this play? • Again, it can be read as a play of opposites, facing both ways at once: towards the past and the present, optimistic and pessimistic. • The 20 th century children of Act 2, scene 7, could imply that sectarianism, the negative influence of Calvinism (extreme Protestantism), and patriarchal ‘macho’ Scotland is set to continue – that we cannot escape our past; • Or: that our myth-history has been reduced to ordinary, everyday dimensions – our prejudices merely childish – and so can be challenged and changed. 24

Liz lochhead last supper

Liz lochhead last supper Box room annotated poem

Box room annotated poem Liz lochhead view of scotland/love poem

Liz lochhead view of scotland/love poem Prayer for negative person

Prayer for negative person Perfect days liz lochhead

Perfect days liz lochhead The bargain liz lochhead

The bargain liz lochhead Authority conformity

Authority conformity Sandra kelman

Sandra kelman Lauren lyall

Lauren lyall Catherine lyall edinburgh

Catherine lyall edinburgh James scott

James scott James russell odom and james clayton lawson

James russell odom and james clayton lawson Clay lawson and russell odom

Clay lawson and russell odom Liz owns stock in nar heating/cooling and cilla shipping

Liz owns stock in nar heating/cooling and cilla shipping Present tense of

Present tense of ____ judy and liz at last month's meeting?

____ judy and liz at last month's meeting? Our reporter sarah hardie

Our reporter sarah hardie Dept of finance and administration

Dept of finance and administration Good hangman phrases

Good hangman phrases Liz quintero

Liz quintero Liz pellicano

Liz pellicano Liz whetham

Liz whetham Liz i've age

Liz i've age Liz sneddon inference

Liz sneddon inference Liz nichols art

Liz nichols art