Intimate Partner Violence Prevention and Resources within the

- Slides: 20

Intimate Partner Violence Prevention and Resources within the VA Health Care System By Ashlyn Nelson and Leigh Gagnon

What is Intimate Partner Violence (IPV)? ● Intimate partner violence describes a pattern of harm by a spouse or partner that can include physical, sexual, psychological, economic, or emotional components, as well as stalking ● IPV is associated with a range of negative health outcomes, including heart, digestive, muscle, bone, reproductive, and nervous system conditions, and survivors can develop mental health disorders such as depression and PTSD as a result. Exposure to IPV increases susceptibility for engaging in risk-taking behaviors It tends to escalate over time, and can cause severe emotional and psychological harm, significant injury, and even death. ● ● The importance of addressing and preventing IPV cannot be overstated.

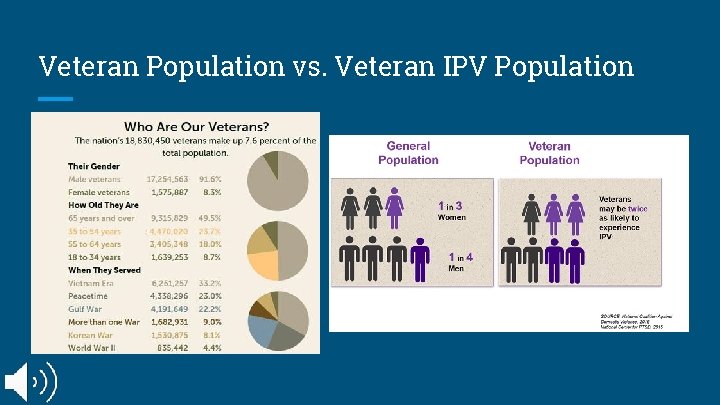

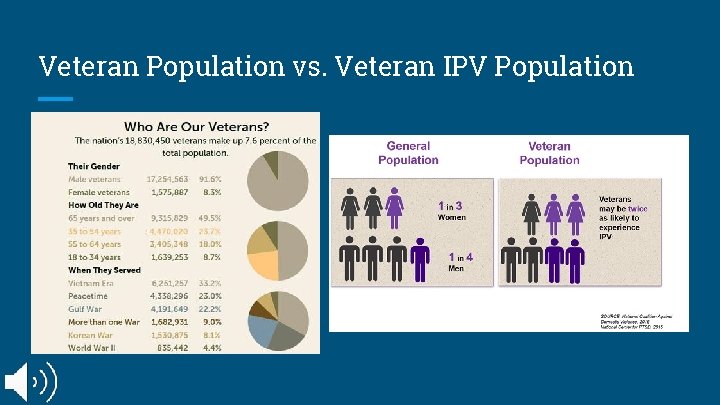

Veteran Population vs. Veteran IPV Population

Why is IPV among Veterans a Significant Health Care Disparity? IPV is a widespread public health problem that can affect individuals and communities regardless of their background and demographics, but factors associated with military service can contribute to an increased risk of IPV use among Veterans. The many negative impacts of IPV on Veterans and their families have prompted the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to begin investigating ways to combat it through preventative and therapeutic interventions. The Veterans Health Administration released VHA Directive 1198 in 2019, establishing the Intimate Partner Violence Assistance Program (IPVAP) to provide support to individuals who experience IPV, as well as those who use it. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, screening protocols have had to be adjusted due to telehealth and social distancing guidelines. Due to these new guidelines, Veteran’s may not feel safe to discuss their IPV situation through video and phone calls and would rather go to the VA where they know it is safe to express their thoughts and feelings.

VA’s IPV and Covid-19 informational video ● COVID-19 has caused increased rates of IPV ● Due to the lack of resources at this time, more Veterans are feeling unsafe and feel like they are unable to get help. How is the VA addressing this issue within the pandemic?

Current Standards of Care - - To help identify Veterans in need of IPV services and assess the potential risk for serious injury or lethal harm, local VA Medical Centers (VAMC) and Outpatient Clinics are encouraged conduct universal IPV screenings for all Veterans served. This screening primarily focuses on those who experience IPV. However, as some Veterans engage in bi- directional forms of IPV, both experiencing and using in the context of their intimate relationships, the screening often leads to a discussion of Veterans’ own behaviors and focuses on developing healthy relationships. Those Veterans who endorse experiencing IPV are then assessed for risk and offered safety planning during the same episode of care. Regardless of screening outcome, all Veterans are offered information and resources such as the National Domestic Violence Hotline contact information, the local IPVAP Coordinator contact information, and general information on safe and healthy relationships.

Current Standards of Care Individuals convicted of IPV-related offenses are often required to participate in a Batterer Intervention Program (BIP) as part of their sentence. These programs are typically community-based interventions intended to help participants build accountability, recognize the negative effects of violent relationships, and identify healthy relationships. Unfortunately, these programs are often ineffective, which can lead to further violence and recidivism, causing further harm. A need has been highlighted for research into more effective programming to help treat underlying causes of IPV and reduce recidivism rates. In coming months, the VHA is set to begin widespread implementation of Strength at Home, an IPV-intervention program targeted for Veterans, addressing use of violence in relationships and related symptoms of PTSD, anger, and aggression. It is hoped that this program can serve as an alternative to traditional BIPs for Veterans who are justice-involved due to IPV-related charges, and could offer them a specialized form of intervention geared to military-specific factors.

Roles of Integrated Healthcare in IPV Response - Universal screening for IPV in inpatient and outpatient settings, with particular focus on vulnerable groups, such as women, homeless, and LGBTQ+ Veterans - Veterans who screen positive will be offered safety planning and resources to the degree that they wish - Social work and mental health services are co-located to facilitate referrals - COVID-19 has made screening more difficult, particularly with shifts to telehealth, demonstrating the need for more research into creating safe methods for screening during virtual visits

VHA Directive 1198 In 2019, the VA issued Directive 1198, establishing the Intimate Partner Violence Assistance Program (IPVAP) in each VA location nationwide - Responsibilities of the program include screening, assessment, and identification, care coordination, intervention, and evaluation of services Based in a trauma-informed and recovery-oriented framework to provide care for both Veterans who experience IPV and Veterans who use IPV in relationships Inclusive of new, broader screening protocols and intervention programming for IPV with couples and individuals

VA Strength at Home Program Strength at Home is a two-pronged initiative made up of cognitive-behavioral group intervention programs for intimate partner violence (IPV): ● ● Strength at Home: A program for those self- or court-identified as having difficulties with using IPV, delivered to individuals within groups, primarily focused on men at this point Strength at Home Couples: A program focused on preventing IPV in couples prior to escalation to physical violence This trauma-informed program seeks to build accountability for violent behaviors in relationships while also helping participants to learn where the behaviors come from and how to prevent them in the future.

Strength at Home vs. Community IPV Intervention Community Batterer Intervention Programs: Started begin established in the late 1970 s, and have rapidly increased in the last 20 years NC requires a minimum for 26 weeks for program completion, but it varies from state to state Often strongly aligned with Duluth Model and Power and Control Wheel Strong emphasis on accountability and responsibility Coordination with criminal justice system Monitored and regulated by the state Strength at Home Program: Pilot study published 2013; rollout began in the last 2 years and is not fully complete yet 12 sessions (roughly 12 weeks) Emphasis on accountability, but also PTSD, trauma, and the influence of military training/experiences on relationships Trauma-informed Monitored and implemented by the VA

VA Relationship Health & Housing Instability Pilot In 2020, the VA ran a pilot initiative to begin screening all Veterans participating in the Healthcare for Homeless Veterans program (HCHV) for relationship safety - The results of the initiative demonstrated an underserved need for IPV treatment and resources for Veterans experiencing homelessness - Demonstrated the need for more research on the impacts of IPV and homelessness on male Veterans - Staff reported that training providers to provide the relationship health and safety screening helped to improve their comfort with the topic - By providing information to all Veterans that they met with, even Veterans who did not endorse IPV experiences could feel more comfortable talking about it with providers in the future if needed

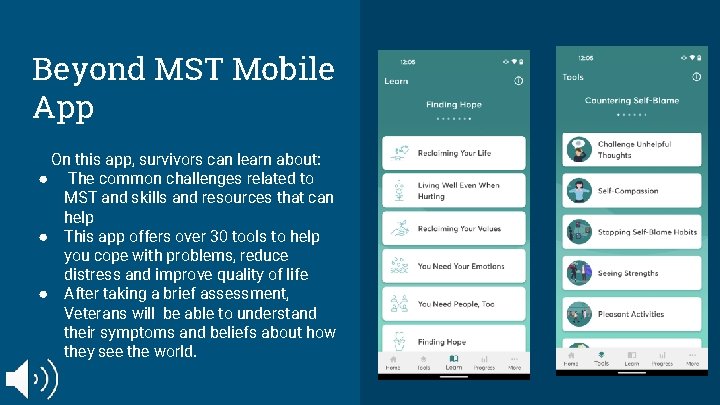

Beyond MST Mobile App ● ● ● Military sexual trauma (MST) is the VA’s term for sexual assault or sexual harrasment that occured during military service. Veterans of all genders and backgrounds have experienced MST. The Beyond MST app was created for survivors of military sexual trauma. This app is free to all Veterans and provides resources to help survivors cope with challenges related to MST. This app can be used by Veterans who are in treatment as well as those who are not. Beyond MST is not intended to replace treatment with a provider. The VA introduced this app in March 2021 in response to the high rate of MST and IPV seen in Veterans

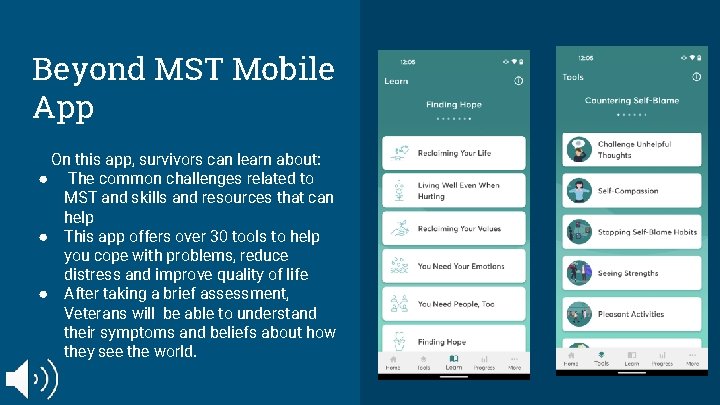

Beyond MST Mobile App On this app, survivors can learn about: ● The common challenges related to MST and skills and resources that can help ● This app offers over 30 tools to help you cope with problems, reduce distress and improve quality of life ● After taking a brief assessment, Veterans will be able to understand their symptoms and beliefs about how they see the world.

Recommendations for Integrated Healthcare Providers who treat IPV among Veterans 1. Prioritizing trauma-informed care in IPV intervention and treatment 2. Implementation of universal screening for all Veterans, regardless of gender identity or background 3. Patient-centered documentation is recommended by research

Trauma-Informed Care Trauma-informed care is particularly important in working with Veterans who experience or use IPV, not only because of the trauma that can result from IPV, but because of the high rates of PTSD and trauma among Veterans. Key Elements of Trauma-Informed Care: 1. Realize that trauma is pervasive and can cause a wide range of effects and impacts on people’s lives 2. Recognize signs of trauma, and that not all signs are visible 3. Respond appropriately to disclosures by having a protocol in place and by validating the emotions of the survivor 4. Resist retraumatizing by providing a calm, safe environment and giving the survivor as much agency in the process as possible

Documentation & Screening Documentation Patient-Centered Documentation honors patient preferences regarding how reports of IPV are recorded in electronic records. Universal Screening • • Universal screening is key to ensure that Veterans have access to necessary services and treatment Telehealth Screening - During COVID-19, screening for IPV in telehealth visits has been a challenge due to the safety concerns for assessing relationship safety when the Veteran is at home for the visit Providers conduct environmental safety checks before starting a visit to ensure that the Veteran is safe, and are advised to ask yes or no questions as part of sensitive screening to allow Veterans to answer non-verbally if needed, including asking about sending emergency assistance More resources may be needed to provide additional supports and safety measures, such as secure messaging

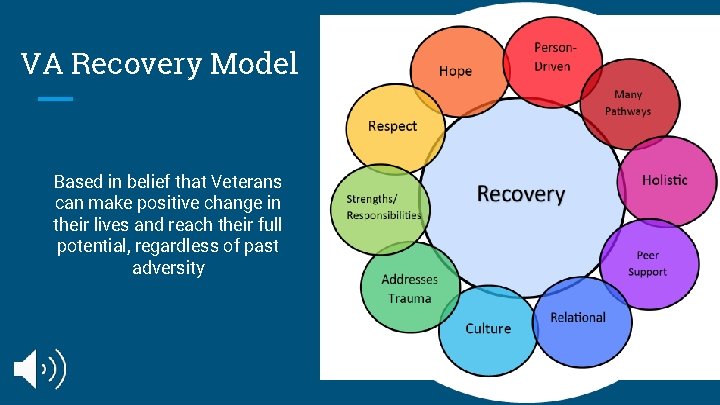

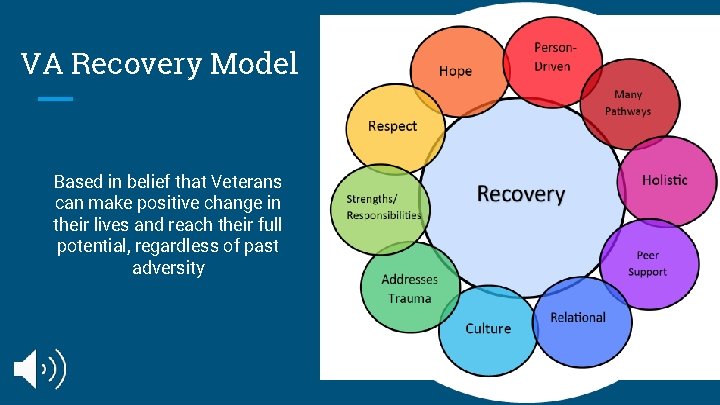

VA Recovery Model Based in belief that Veterans can make positive change in their lives and reach their full potential, regardless of past adversity

References Brown, M. J. , Weitzen, S. , & Lapane, K. L. (2013). Association between intimate partner violence and preventive screening among women. Journal of Women’s Health 22(11): 947 -952. Centers for Disease Control. (2019). Preventing intimate partner violence. Retrieved from: https: //www. cdc. gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv-factsheet 508. pdf Department of Veterans Affairs. (2019). Veterans Health Administration Directive 1198: Intimate partner violence assistance program. Retrieved from: file: ///C: /Users/Owner/Downloads/1198_D_2019 -01 -24. pdf Department of Veterans Affairs. (n. d. ) Mental health and recovery at the VA. Retrieved from: https: //www. mentalhealth. va. gov/communityproviders/docs/recovery. pdf Iverson, K. M. , Omonyêlé, A. , Grillo, A. R. , Dichter, M. E. , Gutner, C. A. , Hamilton, A. B. , Wiltsey Stirman, S. , & Gerber, M. R. (2019). Intimate partner violence screening programs in the Veterans Health Administration: Informing scale-up of successful practices. Journal of General Internal Medicine 34 (11): 2435– 42. Kwan, J. , Sparrow, K. , Facer-Irwin, E. , Thandi, G. , Fear, N. T. , & Mac. Manus, D. (2020). Prevalence of intimate partner violence perpetration among military populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aggression and violent behavior, 53, 101419. North Carolina Administrative Code, Tile I Chapter 17 (2017). http: //reports. oah. state. nc. us/ncac/title%2001%20%20 administration/chapter%2017%20%20 council%20 for%20 women/chapter%2017%20 rules. pdf North Carolina Countil for Women. (2013). North Carolina batterer intervention programs: A guide to achieving recommended practices. Retrieved from: https: //files. nc. gov/ncdoa/Batterer. Intervention. Handbook. pdf The NCSL Blog. (n. d. ). Retrieved March 22, 2021, from https: //www. ncsl. org/blog/2017/11/10/veterans-by-the-numbers. aspx US Department of Veterans Affairs, V. (2017, July 24). VA. gov: Veterans Affairs. Retrieved March 22, 2021, from https: //www. socialwork. va. gov/IPV/Index. asp Veterans Affairs Intimate Partner Violence Assistance Program. (n. d. ) Strength At Home: Program fact sheet. Retrieved from: file: ///C: /Users/Owner/Downloads/VAMHCS%20 Strength%20 at%20 Home%20 Program%20 Information. pdf Veterans Affairs VISN 5 Mental Illness Resarch, Education, and Clinical Center. (2020). Using the guiding principles of recovery to cope during physical distancing. Retrieved from: https: //www. mirecc. va. gov/visn 5/Resource_E-Blasts/e-blast_docs/Recovery_Physical. Distancing_Resource. Blast_Final_04232020. pdf Yorke, N. J. , Friedman, B. D. , & P. Hurt. (2010). Implementing a batterer’s intervention program in a correctional setting: A tertiary prevention model. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation. 49(7): 456 -78.

This project was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U. S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Behavioral Health Workforce Education and Training (BHWET) Program under M 01 HP 31370, UNC-Prime. Care , $1, 920, 000. 00, or the Opioid Workforce Expansion Program -- Professional, under T 98 HP 33425, UNCPrime. Care-OUD , $1, 350, 000. Both programs are 100% financed with governmental sources. This information or content and conclusions are those of the author/s and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U. S. Government.