Instructional Level Theory Timothy Shanahan University of Illinois

- Slides: 40

Instructional Level Theory Timothy Shanahan University of Illinois at Chicago www. shanahanonliteracy. com

Field Distinctions • My field of study focuses on the teaching of reading to native speakers (specifically to native English speakers) • There are other scholars in my society who focus specifically on teaching reading to language-minority students (non-English speakers who live in an English-dominant society) • Most of you are interested in the teaching and learning of a second-language (English-learners who are learning English as a foreign language)

These Distinctions are Important The distinctions among native language, language minority and foreign language teaching are important Those differences include: • Significance or importance (value) of the second language • Availability of conflicting or competing skills or prior knowledge • Sociocultural context (including language status) • Etc.

The Point • I have expertise and knowledge that might be of value to you • However, that knowledge comes from a different field of study (a field that has different issues, concerns, and circumstances) • I will try to tell you what we are learning in our work with native language English speakers— and you will have to decide on its relevance and its significance for the teaching and learning of English in your pedagogical contexts • I am not making claims for teaching English in a foreign language

The Issue to be Discussed • How difficult should be the texts that we use to teach reading? • Are students more likely to learn if the books are matched to student language levels? • What does research say about text difficulty and learning?

History of Text Difficulty (Levels) in English-Language Reading Historically, much attention has been paid to text difficulty in the teaching of reading • During the 19 th century, textbook designers produced graded reading books (Grades 1 -8) • We don’t know how these texts were constructed, but the books for the younger children were easier to read than the ones for older students • The content became more sophisticated, but the language of the books also gradually got harder •

History of Text Difficulty (Levels) in English-Language Reading (cont. ) In urban areas, teachers would teach reading to classes of students at the same grade level (everyone would be at the same age level, except for some older students who had been retained for not learning) • In rural areas, one teacher would teach students of many age levels within one classroom • However, in both situations students were matched to reading books by the age levels of the students •

Problem • • Many students were failing to learn to read Each year, as they progressed through school, the books got harder and the students fell further and further behind • This pedagogical situation continued throughout the first-half of the 20 th Century (with large numbers of students retained)

Readability • Although textbook authors understood generally how to make texts easier or harder, they left behind no ”system” for accomplishing this • That began to change in the 1920 s • Scholars began studying what made one text more or less comprehensible than another and to try to measure “readability” objectively • First study of readability focused on the difficulty of science texts for junior high school students (Lively & Pressey, 1923)

Readability (cont. ) • • • Such studies continued throughout the 1920 s, 1930 s, and 1940 s Initially, the studies tried to identify all of the potential text variables that could affect meaning Gray & Leary (1935) identified more than 110 such variables many of which turned out to be too hard to measure Various formulae were created that were capable of predicting reading comprehension 1950 s-1960 s field turns towards efficient measurement of readability (e. g. , fewest variables)

What We Have Learned about Texts (cont. ) • Readability is not a measure of text difficulty but more of a prediction: rewriting a text to change its rating doesn’t change its difficulty • Only two variables are needed for good prediction (vocabulary and syntax) • Readability measures do a reasonably good job in arraying a wide range of texts, but they are not capable of making fine distinctions • Readability levels do not reveal why a text is difficult or who will have difficulty with it • Reader variables matter too (it is not just text difficulty)

Instructional Level and Reading • Emmett Betts formulates theory of instructional level (1946) • According to Betts, all readers have three performance levels • Independent (fluency 99 -100%; comprehension 90 -100%) • Instructional (fluency 95 -98%; comprehension 75 -89%) • Frustration (fluency 0 -92%; comprehension 0 -50%)

Instructional Level and Reading (cont. ) • Teachers need to test students reading to identify their instructional levels • Originally, this was done with the actual books the teacher might use (later with books at the different readability levels) • Betts claimed that his doctoral student conducted a study showing that greater learning was obtained when students were placed in instructional level (Kilpatrick, 1942)

Foreign Language Teaching • Krashen’s theory of second language acquisition • Students will learn best when teaching presents students with comprehensible input in the following configuration i+1 in which i is the current L 2 language level of the student and + 1 is a text/language sample slightly beyond i

Comparison Betts & Krashen • Both are unproven theories • Both believe that it is possible to identify students’ language/reading levels and text levels accurately • Both believe students learn most when they exert a small amount of cognitive strain – but that when there is too much or too little strain there is less learning • Both believe much (all) of the reading comes from the student reading text and figuring out the messages • Betts more specific about the level of the text than Krashen

Matching texts to student levels doesn’t improve achievement • Killgallon (1942): study that Betts touted as proving the existence of instructional level and its benefits for instruction • However, it was not that kind of a study • All that they showed was that a small group of 9 -year-olds were able to maintain 75 -89% comprehension when they made 5 oral reading errors per 100 words • No teaching, no learning, no evidence that placing students at an instructional level was facilitating • This study could not prove Betts’ theory (and if done with EFL students, couldn’t prove Krashen either)

Matching texts to student levels doesn’t improve achievement • Powell (1968) thought there was an instructional level, he just thought that it wasn’t measured properly • Using the same research methodology as Killgallon, Powell tested larger groups of students from multiple grade levels • He found that the relationship of oral reading fluency and reading comprehension differed by grade levels – at some grades students seemed able to be able to tolerate greater amounts of disfluency (in other words, there were multiple instructional levels) • He concluded that the instructional level required more challenging texts than Betts claimed

Matching texts to student levels doesn’t improve achievement • Dunkeld (1981): Conducted descriptive study of 7 year-olds • He tested them at beginning of school year to find out the fluency accuracy and comprehension of students with the books they were being taught from • He tested them at the end of the year to identify how much learning gain they made • He found that students who were placed at more challenging text levels (about 10 more reading errors per 100 words) than Betts claimed, made the greatest learning gains

Matching texts to student levels doesn’t improve achievement • Jorgensen, et al. (1977): no relation between placement and achievement gains • Tested 8 -, 9 -, 10 -year-old boys at beginning of school year • Calculated the difference between their instructional level and the level of books they were being taught from • Found no relationship between their text placement and the amount they learned

Matching texts to student levels doesn’t improve achievement • Morgan, et al. (2000): conducted the first experiment of the instructional level idea • Tested 7 -year-old students to determine their instructional levels and then randomly assigned them to three treatment groups • One group taught at instructional level, one taught two grade levels above this, and a third was taught four grade levels above instructional level • At end of year, the groups taught with more demanding texts learned more than the instructional level students • Contradicts both Betts and Krashen

Matching texts to student levels doesn’t improve achievement • Brown et al. (2017): attempted to replicate the Morgan experiment with 8 -year-olds • Ended with the same results: the students taught with more challenging texts—texts beyond Betts’ levels and almost certainly beyond Krashen’s too—learned the most

Matching texts to student levels doesn’t improve achievement • O’Connor et al (2002): conducted experiment with learning disabled 8 -. 9 -, and 10 -year-olds • Randomly assigned them to one of three groups • One group control group, and two received tutored groups • Groups taught with texts at reading level (the highest performers were reading at a beginning second-grade level) or at grade level • Result: instructional level group did better (suggesting that Betts and Krashen were correct) • Biggest advantages were for the lowest readers

Matching texts to student levels doesn’t improve achievement • O’Connor et al (2010) concerned about a confound so she replicated the study with one important change • She required all of the tutors to respond to errors in a consistent fashion (removing the confound) • Ran the same experimental study with that correction and found no differences in learning—students did equally well with the harder texts as with the easier ones

Matching texts to student levels doesn’t improve achievement • Kuhn et al (2006): compared performances of a large group of 7 -year-olds taught at their reading levels through guided reading with others who were taught with grade level materials using a fluency-oriented reading instruction • At end of the year, the grade-level students were outperforming those who were taught at their reading levels • Decided to continue the study an additional year, and the grade-level group extended their advantage • This study directly challenges the Betts claims

Matching texts to student levels doesn’t improve achievement • Homan, et al. (2010): taught 11 -year-old students either at their instructional level or 6 -months to 1 -year above instructional level • At end of year, the two groups had made equal learning gains (text placement made no difference)

Matching texts to student levels doesn’t improve achievement • All these studies examined students learning to read within their own language • However, after nearly 40 years scholars are finally starting to evaluate this approach in the EFL context • Bahmani, et al. (2017): studied 50 Arabic learners of English (ages 18 -26 years old) and found that i+1 text placements led to greater amounts of learning than i-1 text placements • However, these placements into leveled materials were made subjectively by the teachers, so no operational measure of what +1 means

Learning from complex text • Across all of these studies, students placed at the instructional level either did no better than students placed at their grade levels OR the frustration level placements led to greater learning • The one EFL study found that students in the higher placed group did better than the one with the easier placement • Possible that if students had been placed even higher in the EFL study that more learning may have accrued

But does that mean that can we just throw students into difficult text? • No evidence based on learning that shows instructional level works • However, the idea has burgeoned because just placing students in demanding texts that they cannot read well was not working well • Where does that leave us?

Traditional instructional level theory Instructional level theory: learning is facilitated by ensuring students can read instructional texts with relatively good fluency and comprehension; accomplished by placing students in relatively easy texts Reader Level Text Level 2 variables

Powell’s mediated text theory Learning from relatively harder texts is superior because teaching can facilitate/mediate students’ interactions with text in ways that allows students to bridge the gap Mediation Reader Level Text Level 3 variables

Any evidence that this is possible? • Yes, quite a bit • Many studies show that – with scaffolding – students can read “frustration level” texts as if they had been placed in books at their “instructional levels”

Scaffolding an Instructional Level Bonfiglio, Daly, Persampieri, & Andersen, 2006 Burns, 2007 Burns, Dean, & Foley, 2004 Carney, Anderson, Blackburn, & Blessings, 1984 Daly & Martens, 1994 Eckert, Ardoin, Daisey, & Scarola, 2000 Faulkner & Levy, 1999 Gickling & Armstrong, 1978 Hall, Sabey, & Mc. Clellan, 2005 Levy, Nicholls, & Kohen, 1993 Mc. Comas, Wacker, & Cooper, 1996 Neill, 1979

Scaffolding an Instructional Level O’Shea, Sindelar, & O’Shea, 1985 Pany & Mc. Coy, 1988 Rasinski, 1990 Reitsma, 1988 Rose & Beattie, 1986 Sanford & Horner, 2013 Sindelar, Monda, & O’Shea, 1990 Smith, 1979 Stoddard, Valcante, Sindelar, O’Shea, et al. , 1993 Taylor, Wade, & Yekovich, 1985 Turpie & Paratore, 1995 Van. Wagenen, Williams, & Mc. Laughlin, 1994 Weinstein & Cooke, 1992 Wixson, 1986

Reconceptualization of reading • Reading is the ability to make sense of ideas expressed in text—the ability to negotiate the linguistic and conceptual barriers or affordances of a text • It is essential that the texts students work with be hard enough that they be confronted by linguistic and/or conceptual barriers—that is required if learning is to take place • The fewer the barriers--the less opportunity to learn • But the more difficult the barriers, the greater the need for scaffolding, support, explanation, and teaching

Four Unfortunate Teacher Responses to Text Complexity • • Move students to easier text Read text to students Tell students what texts say Ignore the problem

Two Unfortunate Student Responses to Text Complexity • Skip assignments • Do the assignments superficially (oral reading without understanding)

What Should We Do? • Students should come to see English texts as challenges that can be accomplished • They need to recognize that comprehension isn’t on or off, but that there actions they can take to solve the problem • Teachers need to not just teach language, but must give students tools and show them how to solve the problem

Scaffolding Challenging Text Scaffolding Text Features • Complexity of ideas/content • Match of text and reader prior knowledge • Complexity of vocabulary • Complexity of syntax • Complexity of coherence • Familiarity of genre demands • Complexity of text organization • Subtlety of author’s tone • Sophistication of literary devices or data-presentation devices Other Approaches • Provide sufficient fluency • Use stair-steps or apprentice texts • Teach comprehension strategies • Motivation

Scaffolding Challenging Text Scaffolding Text Features • Complexity of ideas/content • Match of text and reader prior knowledge • Complexity of vocabulary • Complexity of syntax • Complexity of coherence • Familiarity of genre demands • Complexity of text organization • Subtlety of author’s tone • Sophistication of literary devices or data-presentation devices Other Approaches • Provide sufficient fluency • Use stair-steps or apprentice texts • Teach comprehension strategies • Motivation

Conclusions • Students can’t learn from a text that they can’t figure out • • • (comprehensible input) But they can learn from texts that may not be understand immediately or easily Student persistence depends upon their awareness that they can succeed in such situations A steady diet of simple English texts restricts/limits the text barriers that students will gain experience with But providing students complex text – without scaffolding, guidance, and teaching – will offer opportunity without ensuring learning Complex text is a useful tool in teaching English reading—do not avoid complex text

Timothy shanahan close reading

Timothy shanahan close reading Donal shanahan

Donal shanahan Smithe and shanahan furniture

Smithe and shanahan furniture Patricia shanahan

Patricia shanahan Cynthia shanahan

Cynthia shanahan Siue human resources

Siue human resources Duo mobile uiuc

Duo mobile uiuc Student accounts illinois state

Student accounts illinois state Net math uiuc

Net math uiuc Robert gagne theory

Robert gagne theory Task analysis instructional design

Task analysis instructional design Sic architecture

Sic architecture Objective of microteaching

Objective of microteaching Maximizing instructional time in the classroom

Maximizing instructional time in the classroom Instructional hierarchy

Instructional hierarchy Marzano's 9 instructional strategies

Marzano's 9 instructional strategies Diamond model of curriculum development

Diamond model of curriculum development Instructional design authoring tools

Instructional design authoring tools Marzano generating and testing hypotheses

Marzano generating and testing hypotheses Instructional procedures examples

Instructional procedures examples Instructional aids examples

Instructional aids examples Dynamic instructional design model

Dynamic instructional design model Definition of instructional technology

Definition of instructional technology Instructional materials definition

Instructional materials definition Self-instructional training example

Self-instructional training example Visual instructional materials

Visual instructional materials Self-instructional training example

Self-instructional training example Instructional materials examples

Instructional materials examples Components of an instructional plan

Components of an instructional plan Instructional materials definition

Instructional materials definition Chief instructional officers california community colleges

Chief instructional officers california community colleges California community college chief instructional officers

California community college chief instructional officers Advantages and disadvantages of assure model

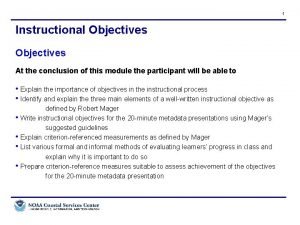

Advantages and disadvantages of assure model Objectives of a conclusion

Objectives of a conclusion Visual instructional media

Visual instructional media Problem-based learning lesson plan examples

Problem-based learning lesson plan examples Addie modeli

Addie modeli Stages of instructional hierarchy

Stages of instructional hierarchy Kemp model example

Kemp model example Tatlong batas moral

Tatlong batas moral Data driven instructional cycle

Data driven instructional cycle