How to select a research topic Shweta Agrawal

- Slides: 28

How to select a research topic Shweta Agrawal IIT Madras

How to select a research topic: A theorist’s perspective

How to select a research topic: A theorist’s perspective

The most important thing before you choose a problem… “ Drop modesty and say to yourself, “Yes, I would like to do first-class work. ” -Richard Hamming

Dropping Modesty ◦ Have the desire to do excellent work ◦ The faith that you can ◦ The willingness to put in what it takes (much toil, many failures and frustration, much patience) Attitude that one starts with is important! But this must be cultivated systematically…

1 THE TWO DIMENSIONS OF PROBLEM CHOICE (From essay by Uri Alon)

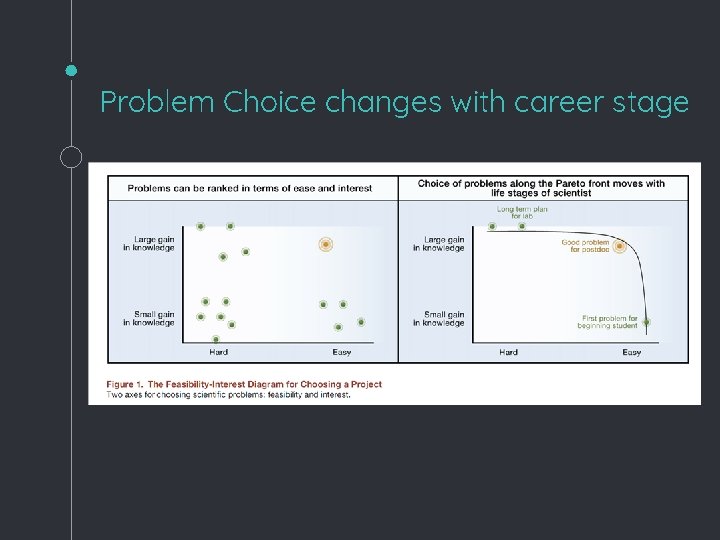

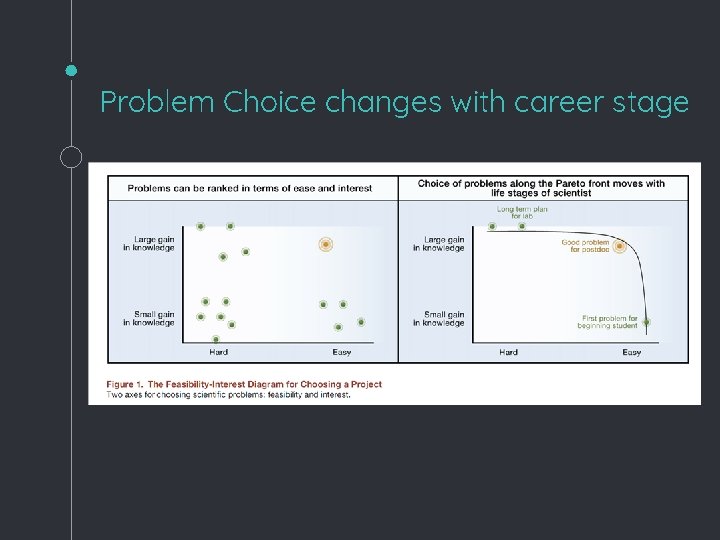

Feasibility Versus Interest ◦Easy-but-not-too-interesting, a. k. a. ‘‘low-hanging fruit. ’’ ◦Both difficult and have low interest: hard equals good? ◦Grand challenges: tough problems with the potential to considerably advance understanding. ◦Desirable: feasible and with high interest, likely to extend our knowledge significantly.

Pareto principle of optimization theory ◦ If problem A is better on both axes (feasibility and interest) than problem B, one can erase B from the diagram. ◦ Applying this criterion to all problems, one is left only with problems for which there are no problems clearly better in both feasibility and interest. ◦ These remaining problems are on the Pareto front ◦ Optimal problems move along the Pareto front as a function of the life stages of the scientist.

Problem Choice changes with career stage

Problem choice in early stages ◦ Maintain healthy balance between hard and reachable ◦ Don’t prematurely obsess on a single “big problem” or “big theory” – Terry Tao ◦ Try to work with other people ◦ Do not be shy to ask for help if things are not working out These are things I learned the hard way

All eggs in one basket: Personal ◦ When I started my postdoc, I worked essentially alone for > 1 year almost exclusively on two big problems ◦ One was solved by another group, one remains open to this day (5 years later) ◦ I felt I was doing something wrong, didn’t discuss ◦ Lost confidence, came close to quitting Upside: Research was never so hard after that

2 TAKE YOUR TIME

Taking the time ◦ It takes time to find a good problem ◦ Do not be in a hurry to “get to work”. Savour the process of finding a nice problem. ◦ Be creative in how you choose the problem. Don’t rush for the first, most obvious question (it gets crowded out there) ◦ Be original. What *you* like is important. Stay committed to what is interesting to you.

3 WHAT IS INTERESTING?

What is interesting? ◦ In the early stages, if you want to be safe, you can tackle modest improvements over papers that appeared in reputable venues ◦ As you gain confidence, branch out to more creative questions ◦ Interesting = publishable? Who decides? What others think is important but not as important as what you think. ◦ If we are genuinely interested, then failures and setbacks (inevitable and plentiful) do not seem so bad

Interesting=Publishable? Personal ◦ Once I got involved in a project because I confused interesting (to me) with publishable ◦ Paper was rejected multiple times. Didn’t really like the question but had to keep coming up with new ways to “sell” it. ◦ Another paper that took equally long to publish but I liked and believed in it. Rewriting helped improve it. Satisfied in the end. Don’t work on things just because you think they are interesting to others.

“ There is confusion due to the mixing of two voices—one is a loud voice of the interests of those around us, in conferences, in our department, etc. The other is a faint voice in our breast, that says, this is interesting to me. Listening to our own idiosyncratic voice leads to better science. -Uri Alon

4 BE INSPIRED

Being inspired while choosing a problem ◦ A concrete method I have is to maintain a stash of papers that I have found innovative, inspiring and cool ◦ I periodically look at these to rediscover what I love about my research area. Keep adding to this stash. ◦When I feel inspired, I try to think of open directions ◦ Choose problems with a fresh mind, e. g. morning

Seeking new problems ◦ Useful to read abstracts of many papers, to know landscape ◦ See many talks/slides to have high level idea of work across the space ◦ Think wild . Forget about details, hurdles etc. Allow the craziest of ideas. Listen to music. Have fun.

“ It is six in the morning. The house is asleep. Nice music is playing. I prove and conjecture. -Paul Erdos

Then, stop being wild and lace up! ◦ After the dreamy phase where all ideas are welcome, play devil’s advocate and try to look at why any one would make sense ◦ Do thorough literature survey. Keep abreast. ◦ Stop reading and start moving. Knowing all the details of all science done is unnecessary (and impossible)

“ ◦When I got (Ph. D) I knew almost nothing about physics. But I did learn one big thing: that no one knows everything, and you don’t have to. -Steven Weinberg

Going for the mess (and sticking on) ◦ My advice is to go for the messes - that’s where the action is –Steven Weinberg ◦Once chosen, be diligent. Don’t give up till you have tried enough, and understand why you are not able to make progress (eg techniques not enough? ) ◦Even if you have to abandon a problem, make sure you learn something from it. Quantify this and write it down.

Keep at it ◦ Talk about research to peers. You’ll get ideas. ◦ Attend and give many talks. Ask many questions. This leads to new problems. ◦ Be sceptical when choosing a problem. Place any question on the map of known results and check if it is surprising.

Being sceptical: Personal ◦ In crypto, we prove security against adversaries (modelled as algorithms) ◦ In one paper in 2011, I could only prove a weaker property than I wanted. The adversary in my proof was limited ◦ I kept trying to generalize the proof and failed each time ◦ In 2016, it occurred to me, is it actually true that the proof can be generalized? ◦ Within half an hour, I had an attack against the scheme, if a general adversary was considered Always ask: can what I am trying to prove true actually be false ?

Final Thoughts ◦ In choosing and later, try to keep the fun alive ◦ Should not become all about slog (though you’ll need to work very hard) ◦ Work hard, but work smart ◦ Get used to failure. Keep learning.

Thank you! References: Richard Hamming: You and your research Uri Alon: How to choose a good scientific problem Steven Weinberg: Four Golden Lessons