DYSMORPHIA DYSPHORIA Engaging Transgender Youth with Eating Disorders

![“. . . the risk for disordered eating in trans individuals, [is] a phenomenon “. . . the risk for disordered eating in trans individuals, [is] a phenomenon](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/34a994fa12c753cbc602380682feb193/image-11.jpg)

- Slides: 24

DYSMORPHIA & DYSPHORIA Engaging Transgender Youth with Eating Disorders in Treatment by Annie David, 2020 -2021 UNC-Chapel Hill Prime. Care Trainee

Table of Contents 01 02 Background Basic definitions and prevalence data Best Practices Screening, assessment and treatment 03 04 Gaps in Care Current issues and affects of COVID-19 Recommendations Improving care and future treatments

01 Background Definitions and data for transgender youth with eating disorders

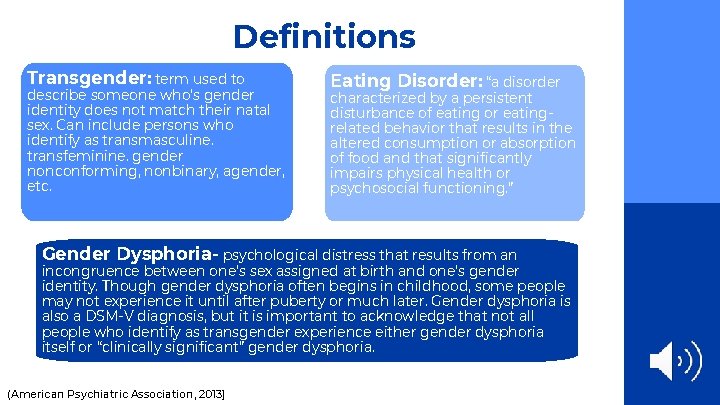

Definitions Transgender: term used to describe someone who’s gender identity does not match their natal sex. Can include persons who identify as transmasculine. transfeminine. gender nonconforming, nonbinary, agender, etc. Eating Disorder: “a disorder characterized by a persistent disturbance of eating or eatingrelated behavior that results in the altered consumption or absorption of food and that significantly impairs physical health or psychosocial functioning. ” Gender Dysphoria- psychological distress that results from an incongruence between one’s sex assigned at birth and one’s gender identity. Though gender dysphoria often begins in childhood, some people may not experience it until after puberty or much later. Gender dysphoria is also a DSM-V diagnosis, but it is important to acknowledge that not all people who identify as transgender experience either gender dysphoria itself or “clinically significant” gender dysphoria. (American Psychiatric Association, 2013)

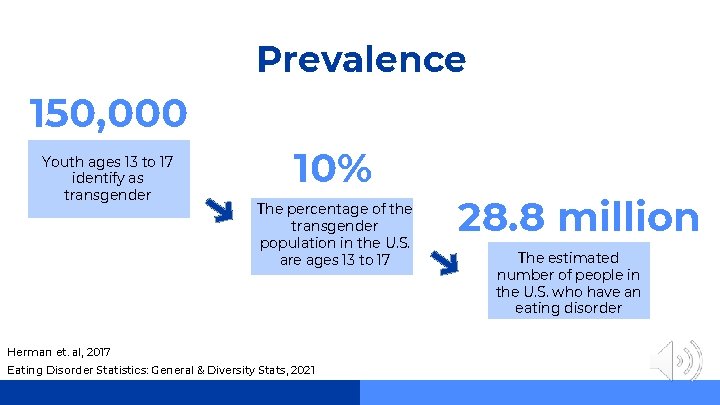

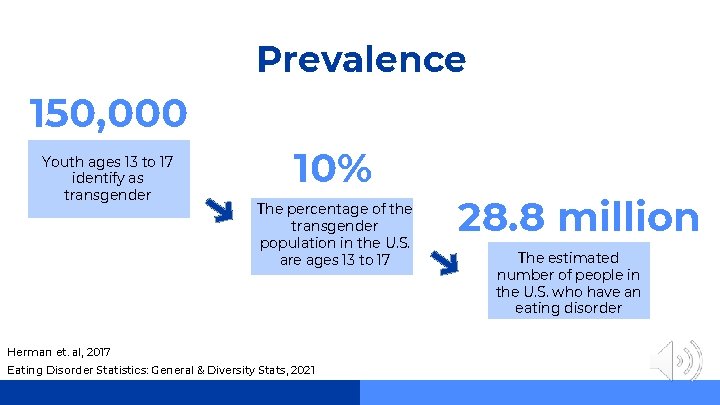

Prevalence 150, 000 Youth ages 13 to 17 identify as transgender 10% The percentage of the transgender population in the U. S. are ages 13 to 17 Herman et. al, 2017 Eating Disorder Statistics: General & Diversity Stats, 2021 28. 8 million The estimated number of people in the U. S. who have an eating disorder

Types of Eating Disorders and DSM-V Criteria Anorexia Nervosa A. Restriction of energy intake relative to requirements, leading to a significantly low body weight in the context of age, sex, developmental trajectory, and physical Design Conduct Synthesize health. Significantly low weight is defined as a weight that is less than minimally normal or, for children and adolescents, less than that minimally expected. B. Intense fear of gaining weight or of becoming fat, or persistent behavior that interferes with weight gain, even though at a significantly low weight. C. Disturbance in the way in which one’s body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or persistent lack of recognition of the seriousness of the current low body weight. (American Psychiatric Association, 2013)

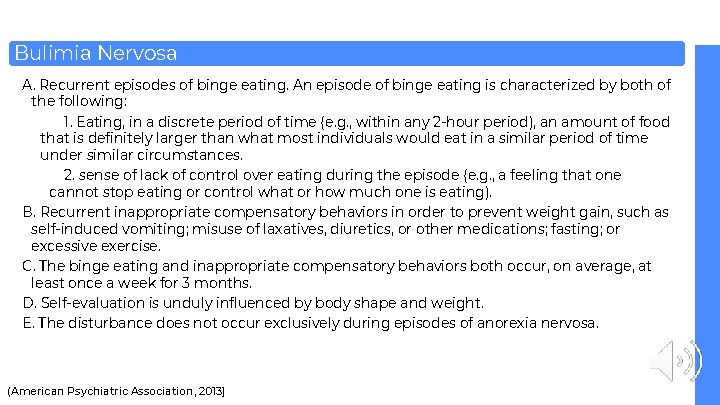

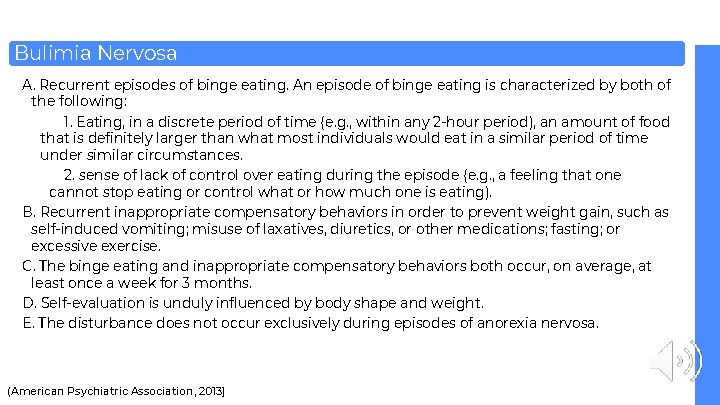

Bulimia Nervosa A. Recurrent episodes of binge eating. An episode of binge eating is characterized by both of the following: 1. Eating, in a discrete period of time (e. g. , within any 2 -hour period), an amount of food that is definitely larger than what most individuals would eat in a similar period of time under similar circumstances. Design Conduct Synthesize 2. sense of lack of control over eating during the episode (e. g. , a feeling that one cannot stop eating or control what or how much one is eating). B. Recurrent inappropriate compensatory behaviors in order to prevent weight gain, such as self-induced vomiting; misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or other medications; fasting; or excessive exercise. C. The binge eating and inappropriate compensatory behaviors both occur, on average, at least once a week for 3 months. D. Self-evaluation is unduly influenced by body shape and weight. E. The disturbance does not occur exclusively during episodes of anorexia nervosa. (American Psychiatric Association, 2013)

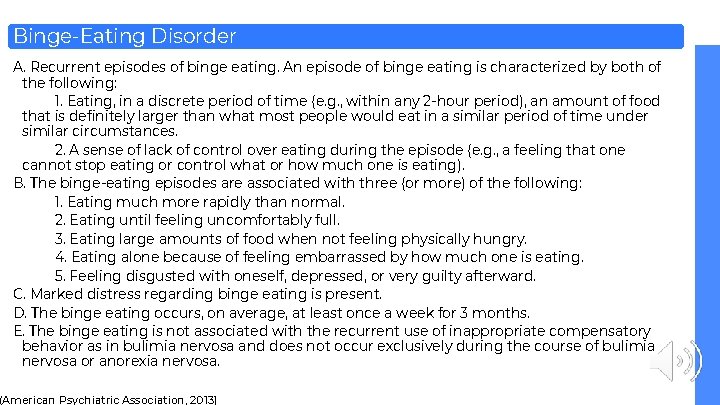

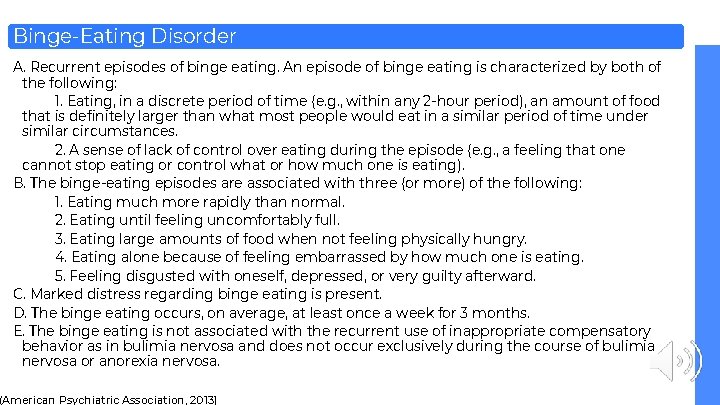

Binge-Eating Disorder A. Recurrent episodes of binge eating. An episode of binge eating is characterized by both of the following: 1. Eating, in a discrete period of time (e. g. , within any 2 -hour period), an amount of food that is definitely larger than what most people would eat in a similar period of time under similar circumstances. 2. A sense of lack of control over eating during the episode (e. g. , a feeling that one Design Conduct Synthesize cannot stop eating or control what or how much one is eating). B. The binge-eating episodes are associated with three (or more) of the following: 1. Eating much more rapidly than normal. 2. Eating until feeling uncomfortably full. 3. Eating large amounts of food when not feeling physically hungry. 4. Eating alone because of feeling embarrassed by how much one is eating. 5. Feeling disgusted with oneself, depressed, or very guilty afterward. C. Marked distress regarding binge eating is present. D. The binge eating occurs, on average, at least once a week for 3 months. E. The binge eating is not associated with the recurrent use of inappropriate compensatory behavior as in bulimia nervosa and does not occur exclusively during the course of bulimia nervosa or anorexia nervosa. (American Psychiatric Association, 2013)

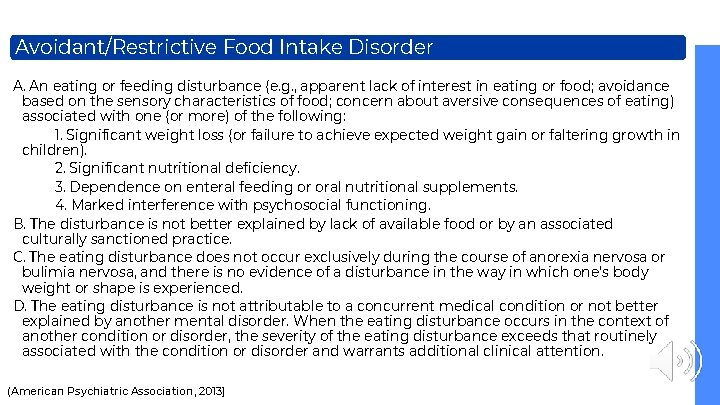

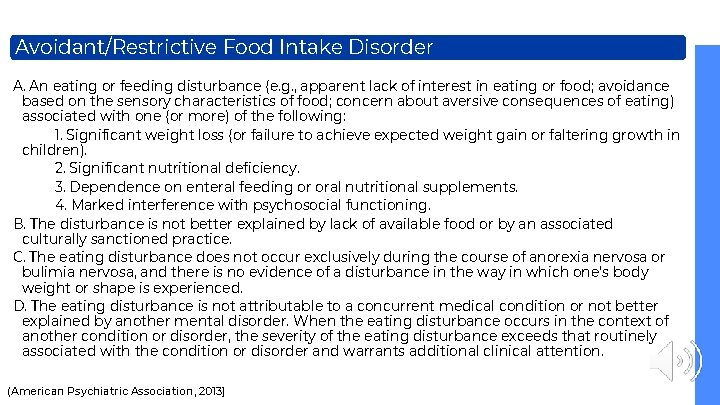

Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder A. An eating or feeding disturbance (e. g. , apparent lack of interest in eating or food; avoidance based on the sensory characteristics of food; concern about aversive consequences of eating) associated with one (or more) of the following: 1. Significant weight loss (or failure to achieve expected weight gain or faltering growth in children). Design Conduct Synthesize 2. Significant nutritional deficiency. 3. Dependence on enteral feeding or oral nutritional supplements. 4. Marked interference with psychosocial functioning. B. The disturbance is not better explained by lack of available food or by an associated culturally sanctioned practice. C. The eating disturbance does not occur exclusively during the course of anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa, and there is no evidence of a disturbance in the way in which one’s body weight or shape is experienced. D. The eating disturbance is not attributable to a concurrent medical condition or not better explained by another mental disorder. When the eating disturbance occurs in the context of another condition or disorder, the severity of the eating disturbance exceeds that routinely associated with the condition or disorder and warrants additional clinical attention. (American Psychiatric Association, 2013)

02 Best Practices Screening, assessment, and treatment for transgender youth with eating disorders

![the risk for disordered eating in trans individuals is a phenomenon “. . . the risk for disordered eating in trans individuals, [is] a phenomenon](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/34a994fa12c753cbc602380682feb193/image-11.jpg)

“. . . the risk for disordered eating in trans individuals, [is] a phenomenon found, in part, to be related to a desire to make changes to body shape in support of gender expression. ” -Coelho et al. , 2019

Prominent Symptoms in Transgender Youth Binge eating Use of unhealthy or compensatory weight management strategies (Coelho et al. , 2019) Purging Fasting

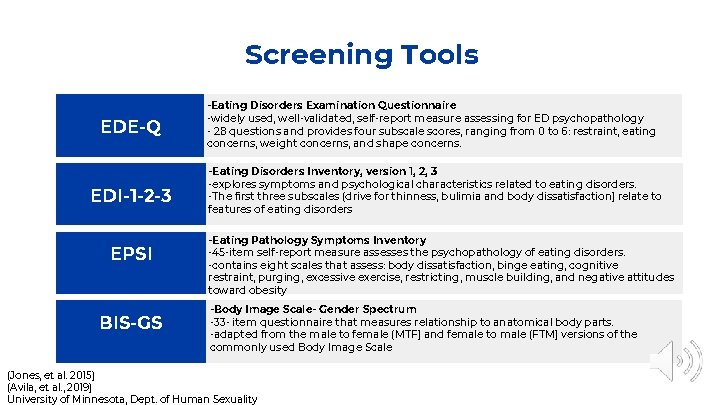

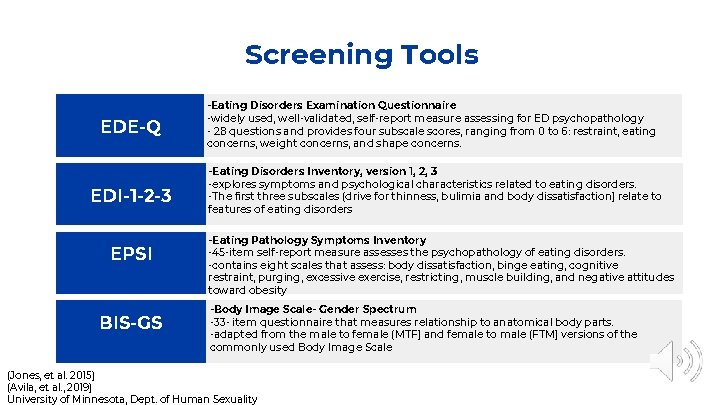

Screening Tools EDE-Q EDI-1 -2 -3 EPSI BIS-GS -Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire -widely used, well-validated, self-report measure assessing for ED psychopathology - 28 questions and provides four subscale scores, ranging from 0 to 6: restraint, eating concerns, weight concerns, and shape concerns. -Eating Disorders Inventory, version 1, 2, 3 -explores symptoms and psychological characteristics related to eating disorders. -The first three subscales (drive for thinness, bulimia and body dissatisfaction) relate to features of eating disorders -Eating Pathology Symptoms Inventory -45 -item self-report measure assesses the psychopathology of eating disorders. -contains eight scales that assess: body dissatisfaction, binge eating, cognitive restraint, purging, excessive exercise, restricting, muscle building, and negative attitudes toward obesity -Body Image Scale- Gender Spectrum -33 - item questionnaire that measures relationship to anatomical body parts. -adapted from the male to female (MTF) and female to male (FTM) versions of the commonly used Body Image Scale (Jones, et al. 2015) (Avila, et al. , 2019) University of Minnesota, Dept. of Human Sexuality

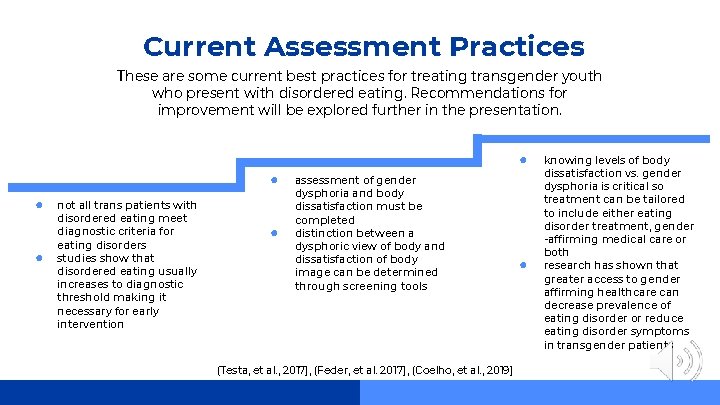

Current Assessment Practices These are some current best practices for treating transgender youth who present with disordered eating. Recommendations for improvement will be explored further in the presentation. ● ● not all trans patients with disordered eating meet diagnostic criteria for eating disorders studies show that disordered eating usually increases to diagnostic threshold making it necessary for early intervention ● assessment of gender dysphoria and body dissatisfaction must be completed distinction between a dysphoric view of body and dissatisfaction of body image can be determined through screening tools (Testa, et al. , 2017), (Feder, et al. 2017), (Coelho, et al. , 2019) ● knowing levels of body dissatisfaction vs. gender dysphoria is critical so treatment can be tailored to include either eating disorder treatment, gender -affirming medical care or both research has shown that greater access to gender affirming healthcare can decrease prevalence of eating disorder or reduce eating disorder symptoms in transgender patients

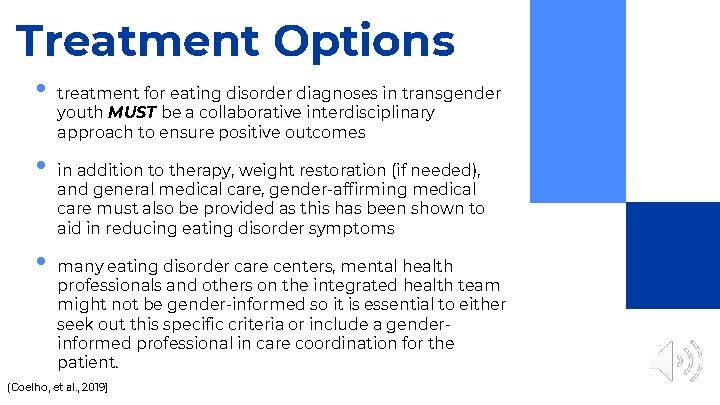

Treatment Options • • • treatment for eating disorder diagnoses in transgender youth MUST be a collaborative interdisciplinary approach to ensure positive outcomes in addition to therapy, weight restoration (if needed), and general medical care, gender-affirming medical care must also be provided as this has been shown to aid in reducing eating disorder symptoms many eating disorder care centers, mental health professionals and others on the integrated health team might not be gender-informed so it is essential to either seek out this specific criteria or include a genderinformed professional in care coordination for the patient. (Coelho, et al. , 2019)

Integrated Care Approach to Treatment General Physical Healthcare • Gender-affirming Healthcare a gender affirming PCP is critical to provide routine check -ups and screening for disordered eating and any increases in gender dysphoria • Mental Health Support • (Coelho, et al. , 2019) a robust mental health team is required to support needs of a transgender patient with disordered eating. This can include a psychiatrist, social worker, therapy provider, etc. Successful Treatment a gender affirming health provide (most likely an endocrinologist) is needed to provided medical treatment for any medical treatment the patient wishes to undergo, including but not limited to gender-affirming hormones, puberty blockers, bleeding management, etc. This is a non-exhaustive list of possible integrated healthcare team members. Other specialists could include OB/GYN, PT, OT, dentist, speech language pathologist, plastic surgeon, etc.

03 Gaps in Care Areas for improvement in providing care for transgender youth with eating disorder diagnoses

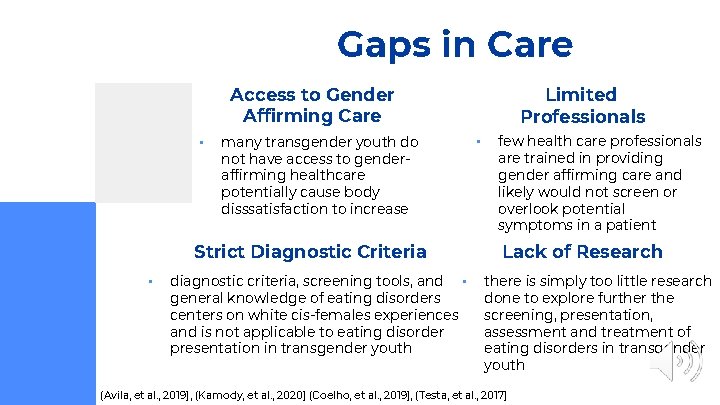

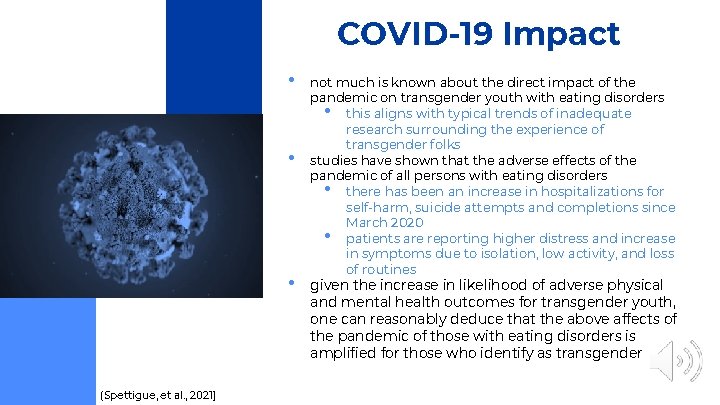

Gaps in Care Access to Gender Affirming Care • many transgender youth do not have access to genderaffirming healthcare potentially cause body disssatisfaction to increase Strict Diagnostic Criteria • diagnostic criteria, screening tools, and • general knowledge of eating disorders centers on white cis-females experiences and is not applicable to eating disorder presentation in transgender youth Limited Professionals • few health care professionals are trained in providing gender affirming care and likely would not screen or overlook potential symptoms in a patient Lack of Research there is simply too little research done to explore further the screening, presentation, assessment and treatment of eating disorders in transgender youth (Avila, et al. , 2019), (Kamody, et al. , 2020) (Coelho, et al. , 2019), (Testa, et al. , 2017)

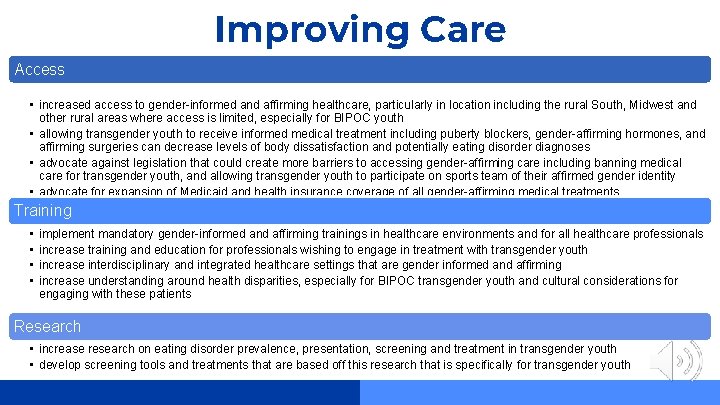

COVID-19 Impact • • • (Spettigue, et al. , 2021) not much is known about the direct impact of the pandemic on transgender youth with eating disorders • this aligns with typical trends of inadequate research surrounding the experience of transgender folks studies have shown that the adverse effects of the pandemic of all persons with eating disorders • there has been an increase in hospitalizations for self-harm, suicide attempts and completions since March 2020 • patients are reporting higher distress and increase in symptoms due to isolation, low activity, and loss of routines given the increase in likelihood of adverse physical and mental health outcomes for transgender youth, one can reasonably deduce that the above affects of the pandemic of those with eating disorders is amplified for those who identify as transgender

04 Recommendations How care can be improved for treating transgender youth with eating disorders

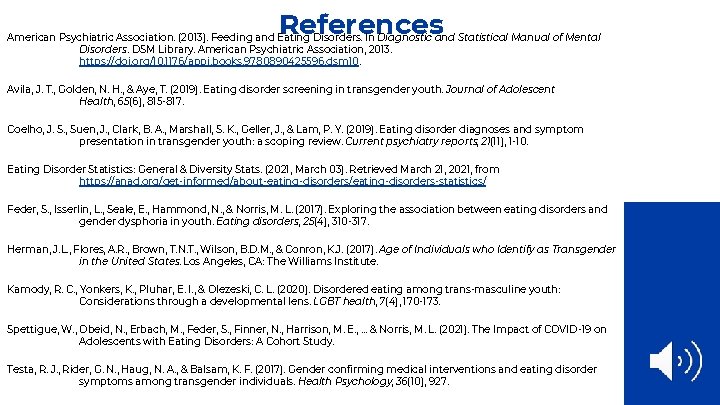

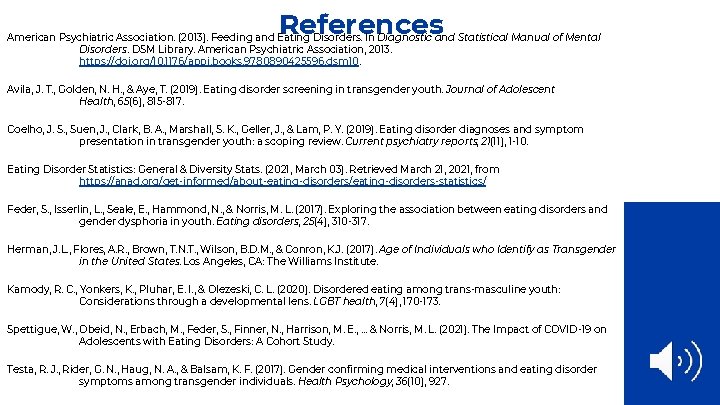

Improving Care Access • increased access to gender-informed and affirming healthcare, particularly in location including the rural South, Midwest and other rural areas where access is limited, especially for BIPOC youth • allowing transgender youth to receive informed medical treatment including puberty blockers, gender-affirming hormones, and affirming surgeries can decrease levels of body dissatisfaction and potentially eating disorder diagnoses • advocate against legislation that could create more barriers to accessing gender-affirming care including banning medical care for transgender youth, and allowing transgender youth to participate on sports team of their affirmed gender identity • advocate for expansion of Medicaid and health insurance coverage of all gender-affirming medical treatments Training • • implement mandatory gender-informed and affirming trainings in healthcare environments and for all healthcare professionals increase training and education for professionals wishing to engage in treatment with transgender youth increase interdisciplinary and integrated healthcare settings that are gender informed and affirming increase understanding around health disparities, especially for BIPOC transgender youth and cultural considerations for engaging with these patients Research • increase research on eating disorder prevalence, presentation, screening and treatment in transgender youth • develop screening tools and treatments that are based off this research that is specifically for transgender youth

Resources ● The Trevor Project ● ● Human Rights Campaign ● ● https: //www. hrc. org World Professional Association for Transgender Health ● ● https: //www. thetrevorproject. org https: //www. wpath. org/ Caring for Transgender and Gender-Diverse Persons: What Clinicians Should Know- AAFP ● https: //www. aafp. org/afp/2018/1201/p 645. html

References American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Feeding and Eating Disorders. In Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. DSM Library. American Psychiatric Association, 2013. https: //doi. org/10. 1176/appi. books. 9780890425596. dsm 10. Avila, J. T. , Golden, N. H. , & Aye, T. (2019). Eating disorder screening in transgender youth. Journal of Adolescent Health, 65(6), 815 -817. Coelho, J. S. , Suen, J. , Clark, B. A. , Marshall, S. K. , Geller, J. , & Lam, P. Y. (2019). Eating disorder diagnoses and symptom presentation in transgender youth: a scoping review. Current psychiatry reports, 21(11), 1 -10. Eating Disorder Statistics: General & Diversity Stats. (2021, March 03). Retrieved March 21, 2021, from https: //anad. org/get-informed/about-eating-disorders/eating-disorders-statistics/ Feder, S. , Isserlin, L. , Seale, E. , Hammond, N. , & Norris, M. L. (2017). Exploring the association between eating disorders and gender dysphoria in youth. Eating disorders, 25(4), 310 -317. Herman, J. L. , Flores, A. R. , Brown, T. N. T. , Wilson, B. D. M. , & Conron, K. J. (2017). Age of Individuals who Identify as Transgender in the United States. Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute. Kamody, R. C. , Yonkers, K. , Pluhar, E. I. , & Olezeski, C. L. (2020). Disordered eating among trans-masculine youth: Considerations through a developmental lens. LGBT health, 7(4), 170 -173. Spettigue, W. , Obeid, N. , Erbach, M. , Feder, S. , Finner, N. , Harrison, M. E. , . . . & Norris, M. L. (2021). The Impact of COVID-19 on Adolescents with Eating Disorders: A Cohort Study. Testa, R. J. , Rider, G. N. , Haug, N. A. , & Balsam, K. F. (2017). Gender confirming medical interventions and eating disorder symptoms among transgender individuals. Health Psychology, 36(10), 927.

This project was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U. S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Behavioral Health Workforce Education and Training (BHWET) Program under M 01 HP 31370, UNC-Prime. Care, $1, 920, 000. 00, or the Opioid Workforce Expansion Program -- Professional, (OWEP) under T 98 HP 33425, UNC-Prime. Care-OUD, $1, 350, 000. Both programs are 100% financed with governmental sources. This information or content and conclusions are those of the author/s and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U. S. Government.

What are the 10 personality disorders

What are the 10 personality disorders Muscle dysmorphia

Muscle dysmorphia Rejection sensitive dysphoria

Rejection sensitive dysphoria Andrea matteliano

Andrea matteliano Dsm v sexual disorders

Dsm v sexual disorders Gender dysphoria biological explanations

Gender dysphoria biological explanations Hypothalamus eating disorders

Hypothalamus eating disorders Eating disorders in uae

Eating disorders in uae Isabelle caro before photos

Isabelle caro before photos Kate moss anorexia

Kate moss anorexia Acupuncture for eating disorders

Acupuncture for eating disorders Psychodynamic approach to eating disorders

Psychodynamic approach to eating disorders An eating disorder in which people overeat compulsively

An eating disorder in which people overeat compulsively Eating disorders brainpop answers

Eating disorders brainpop answers How to be anorexic

How to be anorexic Eat disorder york

Eat disorder york Chapter 18 eating and feeding disorders

Chapter 18 eating and feeding disorders How to spot eating disorders

How to spot eating disorders Dynamisch verbinden

Dynamisch verbinden Marketing involve engaging directly with carefully targeted

Marketing involve engaging directly with carefully targeted Marketing involve engaging directly with carefully targeted

Marketing involve engaging directly with carefully targeted Fundal level

Fundal level Cisgender

Cisgender Gnc knoxville tn

Gnc knoxville tn Genderkoek cavaria

Genderkoek cavaria