Chapter 14 Conflict and Negotiation CrossCultural Issues modified

- Slides: 43

Chapter 14 Conflict and Negotiation: Cross-Cultural Issues modified by Jeffrey M. Wachtel ORGANIZATIONAL BEHAVIOR S T E P H E N P. R O B B I N S E L E V E N T H © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. E D I T I O N WWW. PRENHALL. COM/ROBBINS Power. Point Presentation by Charlie Cook

Conflict Ø Conflict Defined – 1. Is a process that begins when one party perceives that another party has negatively affected, or is about to negatively affect, something that the first party cares about. • 2. Conflict is an intense disagreement process between two interdependent parties over incompatible goals and the interference each perceives from the other in her or his effort to achieve those goals. Stella Ting-Toomey** • California State University at Fullerton © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 1

Transitions in Conflict Thought Traditional View of Conflict The belief that all conflict is harmful and must be avoided. Causes: • Poor communication • Lack of openness • Failure to respond to employee needs © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 2

Thailand Conflict Ø We (I guess like other nations) do not like the aggressive boss. Ø We do not like loud noise or an angry manner in meetings. Ø If we have a strong debating bout in the meeting room with someone, or someone critiques us, we will not forget. Kriengsak Niratpattanasai DBS Thai Danu Bank, Bangkok, Thailand Ø Is the above true? Ø What view of conflict does this national trait represent? © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 3

Transitions in Conflict Thought (cont’d) Human Relations View of Conflict The belief that conflict is a natural and inevitable outcome in any group. Interactionist View of Conflict The belief that conflict is not only a positive force in a group but that it is absolutely necessary for a group to perform effectively. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 4

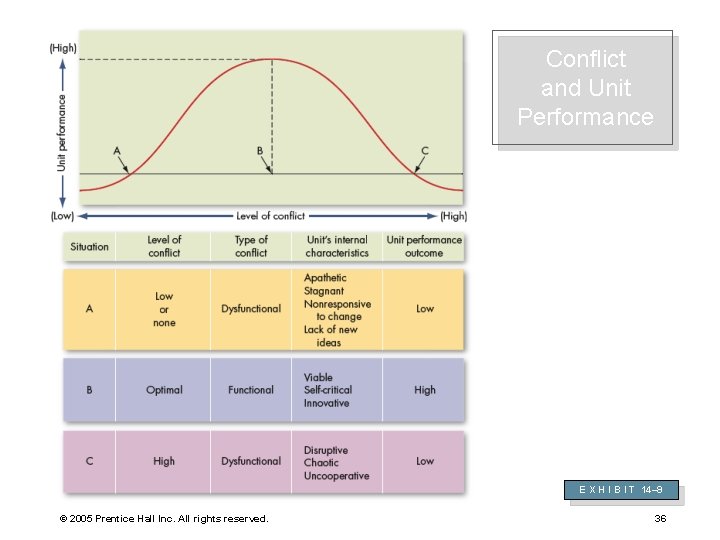

Functional versus Dysfunctional Conflict Functional Conflict that supports the goals of the group and improves its performance. Dysfunctional Conflict that hinders group performance. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 5

Types of Conflict Task Conflicts over content and goals of the work. Relationship Conflict based on interpersonal relationships. Process Conflict over how work gets done. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 6

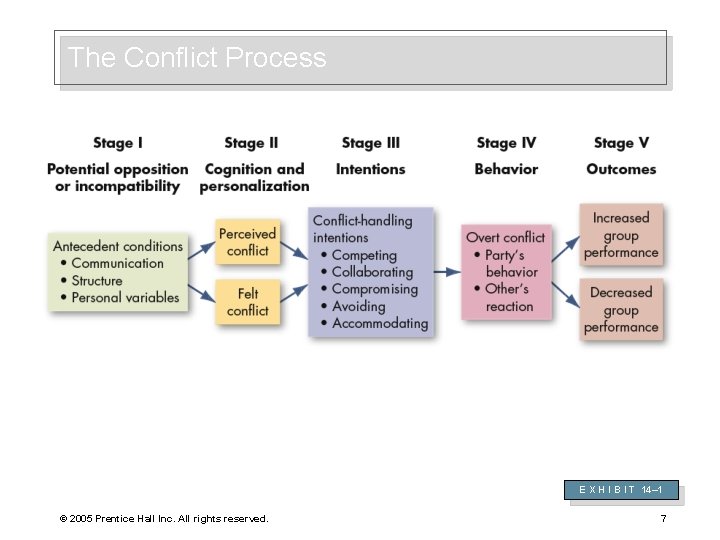

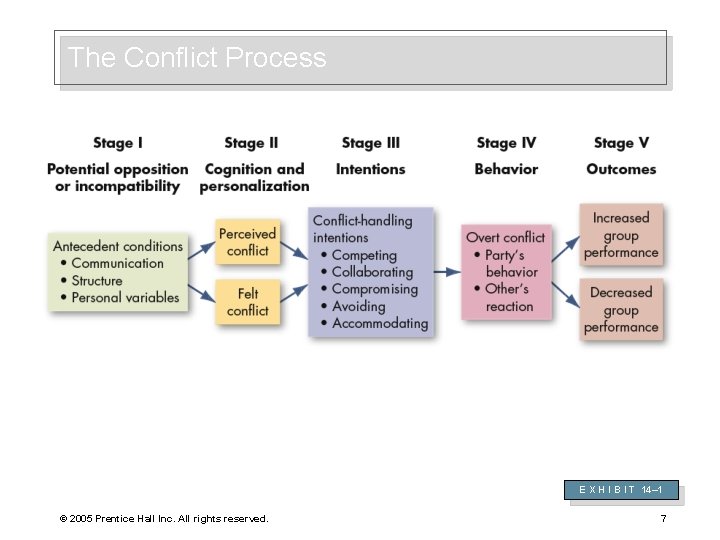

The Conflict Process E X H I B I T 14– 1 © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 7

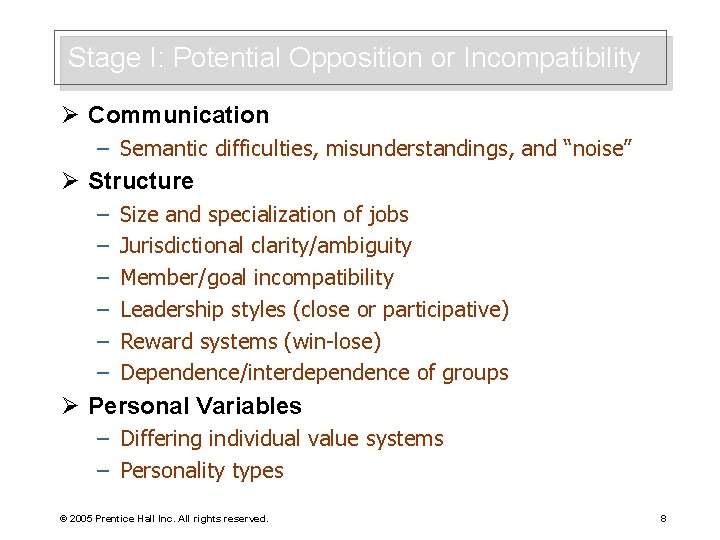

Stage I: Potential Opposition or Incompatibility Ø Communication – Semantic difficulties, misunderstandings, and “noise” Ø Structure – – – Size and specialization of jobs Jurisdictional clarity/ambiguity Member/goal incompatibility Leadership styles (close or participative) Reward systems (win-lose) Dependence/interdependence of groups Ø Personal Variables – Differing individual value systems – Personality types © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 8

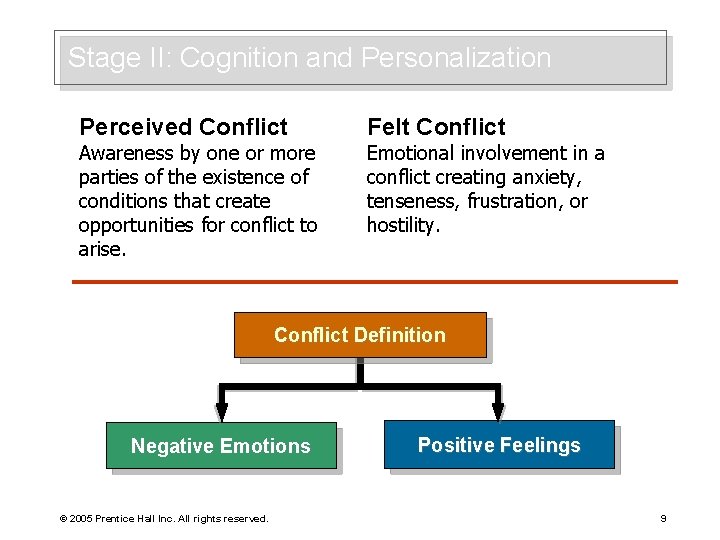

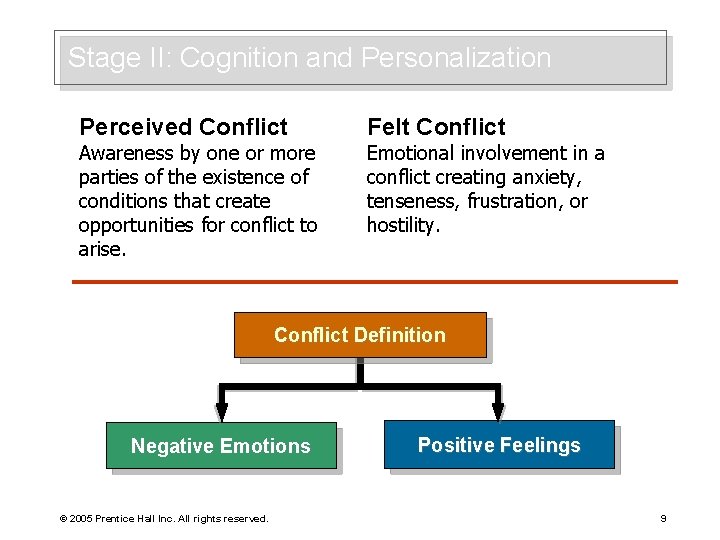

Stage II: Cognition and Personalization Perceived Conflict Felt Conflict Awareness by one or more parties of the existence of conditions that create opportunities for conflict to arise. Emotional involvement in a conflict creating anxiety, tenseness, frustration, or hostility. Conflict Definition Negative Emotions © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. Positive Feelings 9

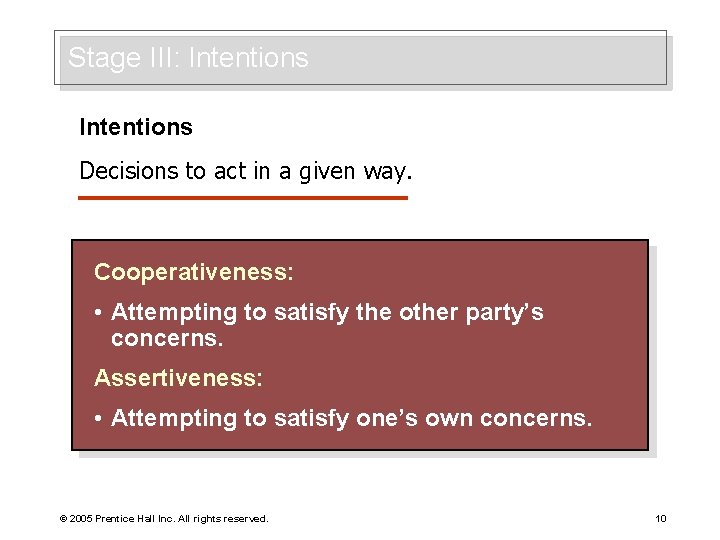

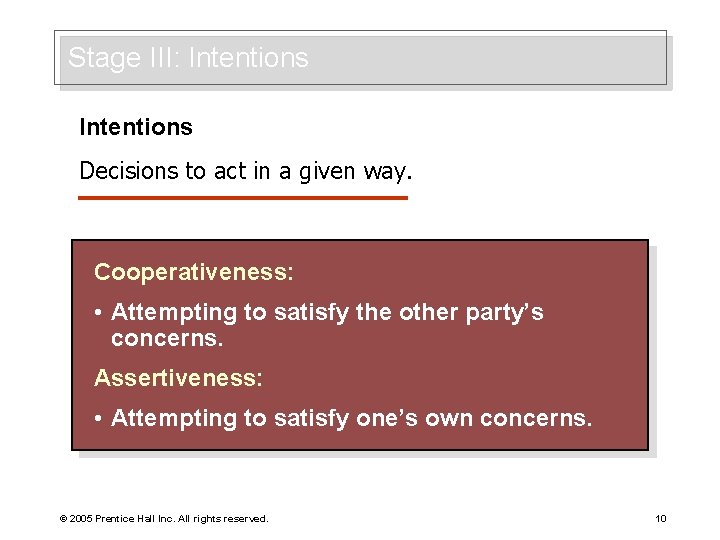

Stage III: Intentions Decisions to act in a given way. Cooperativeness: • Attempting to satisfy the other party’s concerns. Assertiveness: • Attempting to satisfy one’s own concerns. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 10

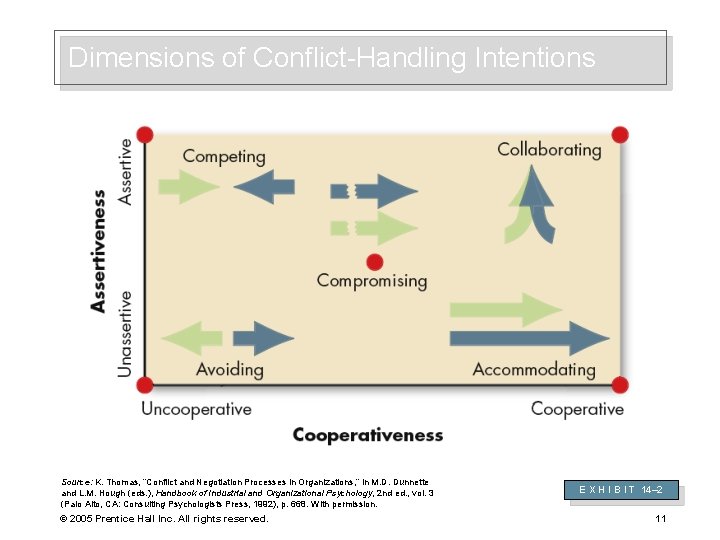

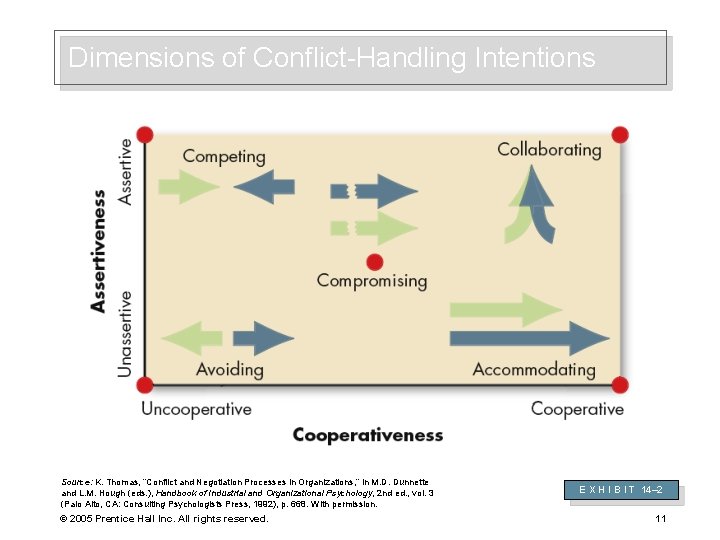

Dimensions of Conflict-Handling Intentions Source: K. Thomas, “Conflict and Negotiation Processes in Organizations, ” in M. D. Dunnette and L. M. Hough (eds. ), Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 2 nd ed. , vol. 3 (Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press, 1992), p. 668. With permission. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. E X H I B I T 14– 2 11

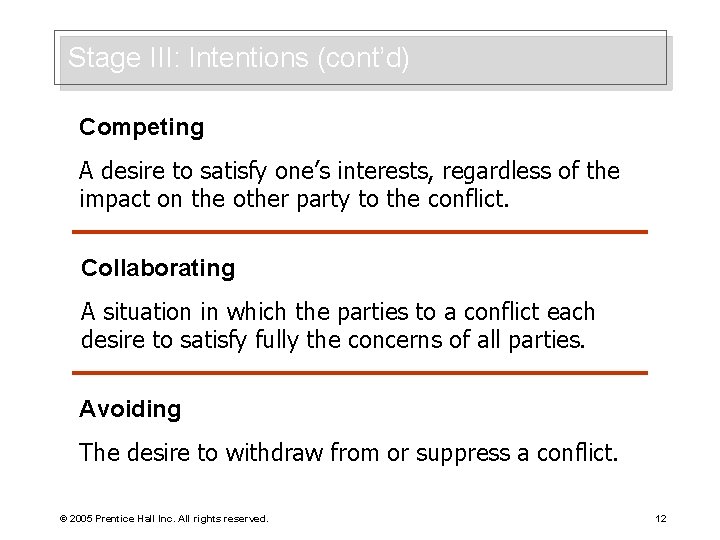

Stage III: Intentions (cont’d) Competing A desire to satisfy one’s interests, regardless of the impact on the other party to the conflict. Collaborating A situation in which the parties to a conflict each desire to satisfy fully the concerns of all parties. Avoiding The desire to withdraw from or suppress a conflict. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 12

Stage III: Intentions (cont’d) Accommodating The willingness of one party in a conflict to place the opponent’s interests above his or her own. Compromising A situation in which each party to a conflict is willing to give up something. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 13

Stage IV: Behavior Conflict Management The use of resolution and stimulation techniques to achieve the desired level of conflict. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 14

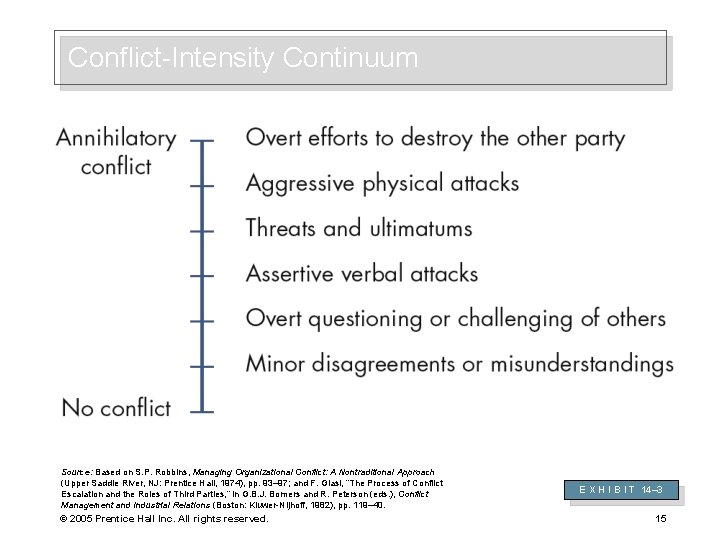

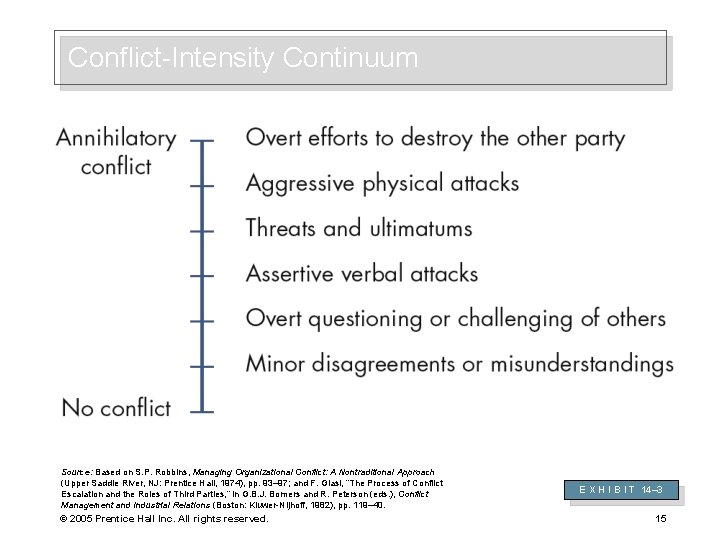

Conflict-Intensity Continuum Source: Based on S. P. Robbins, Managing Organizational Conflict: A Nontraditional Approach (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1974), pp. 93– 97; and F. Glasi, “The Process of Conflict Escalation and the Roles of Third Parties, ” in G. B. J. Bomers and R. Peterson (eds. ), Conflict Management and Industrial Relations (Boston: Kluwer-Nijhoff, 1982), pp. 119– 40. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. E X H I B I T 14– 3 15

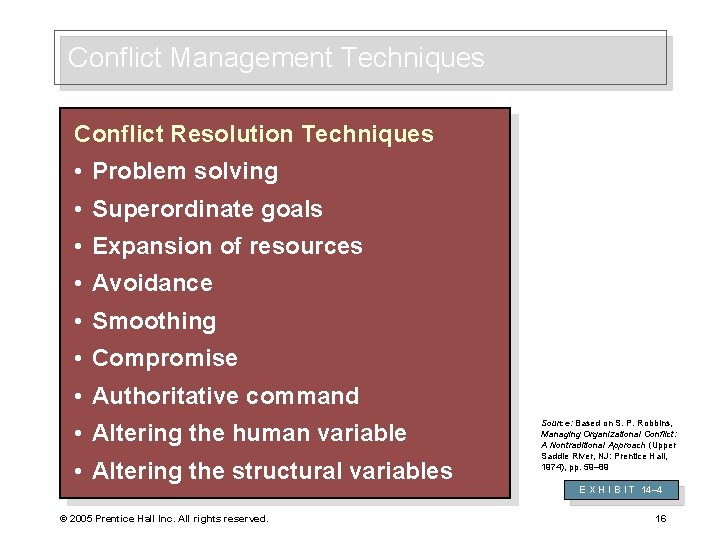

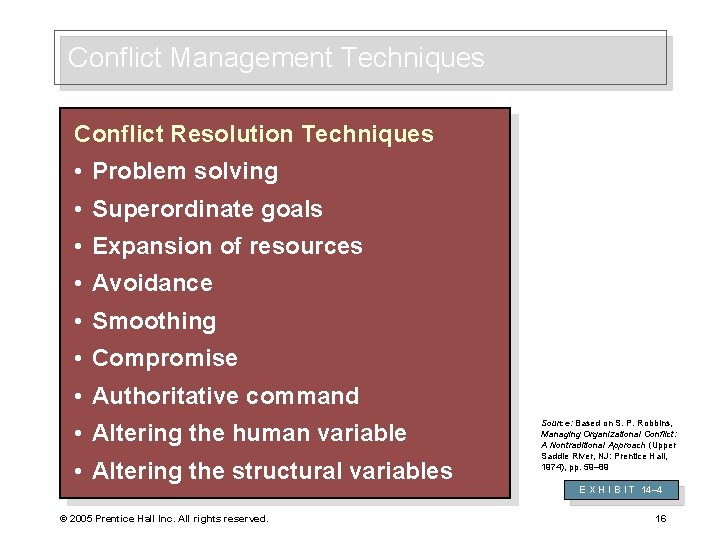

Conflict Management Techniques Conflict Resolution Techniques • Problem solving • Superordinate goals • Expansion of resources • Avoidance • Smoothing • Compromise • Authoritative command • Altering the human variable • Altering the structural variables Source: Based on S. P. Robbins, Managing Organizational Conflict: A Nontraditional Approach (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1974), pp. 59– 89 E X H I B I T 14– 4 © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 16

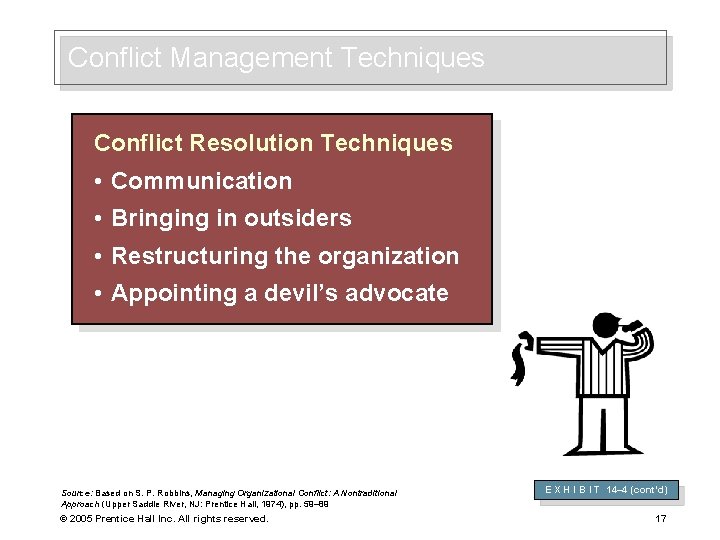

Conflict Management Techniques Conflict Resolution Techniques • Communication • Bringing in outsiders • Restructuring the organization • Appointing a devil’s advocate Source: Based on S. P. Robbins, Managing Organizational Conflict: A Nontraditional Approach (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1974), pp. 59– 89 © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. E X H I B I T 14– 4 (cont’d) 17

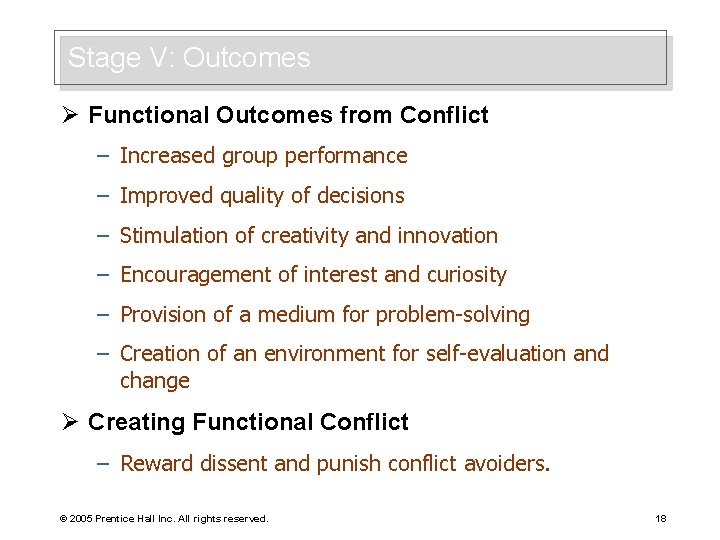

Stage V: Outcomes Ø Functional Outcomes from Conflict – Increased group performance – Improved quality of decisions – Stimulation of creativity and innovation – Encouragement of interest and curiosity – Provision of a medium for problem-solving – Creation of an environment for self-evaluation and change Ø Creating Functional Conflict – Reward dissent and punish conflict avoiders. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 18

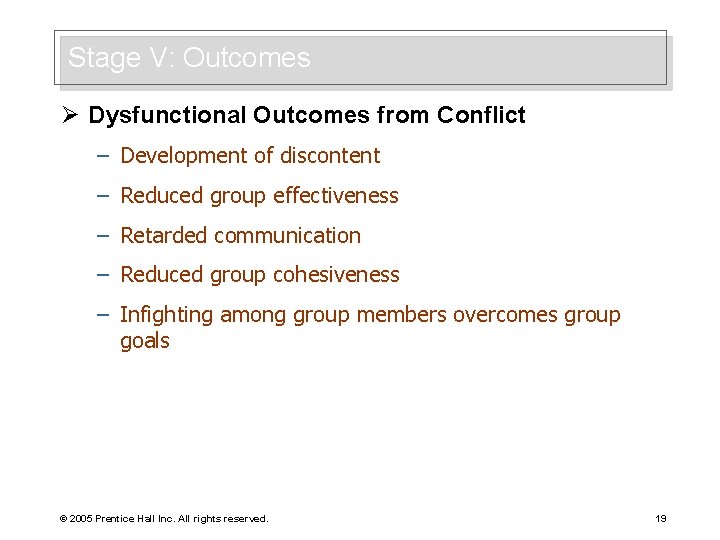

Stage V: Outcomes Ø Dysfunctional Outcomes from Conflict – Development of discontent – Reduced group effectiveness – Retarded communication – Reduced group cohesiveness – Infighting among group members overcomes group goals © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 19

Negotiation A process in which two or more parties exchange goods or services and attempt to agree on the exchange rate for them. BATNA The Best Alternative To a Negotiated Agreement; the lowest acceptable value (outcome) to an individual for a negotiated agreement. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 20

Bargaining Strategies Distributive Bargaining Negotiation that seeks to divide up a fixed amount of resources; a win-lose situation. Integrative Bargaining Negotiation that seeks one or more settlements that can create a win-win solution. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 21

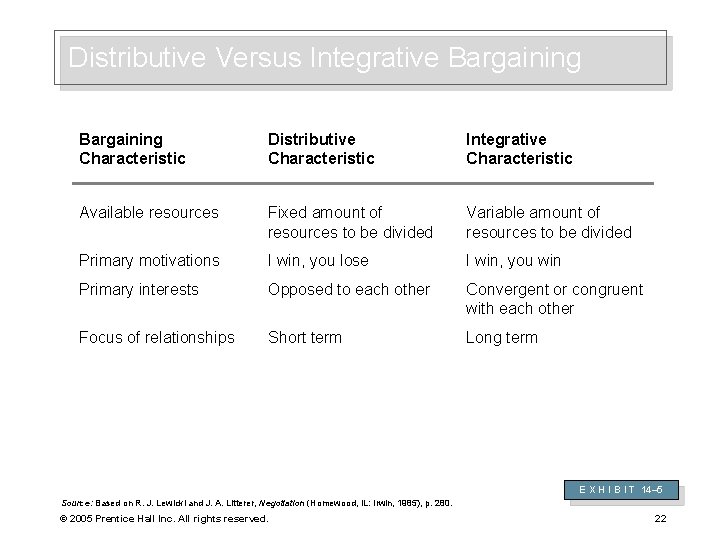

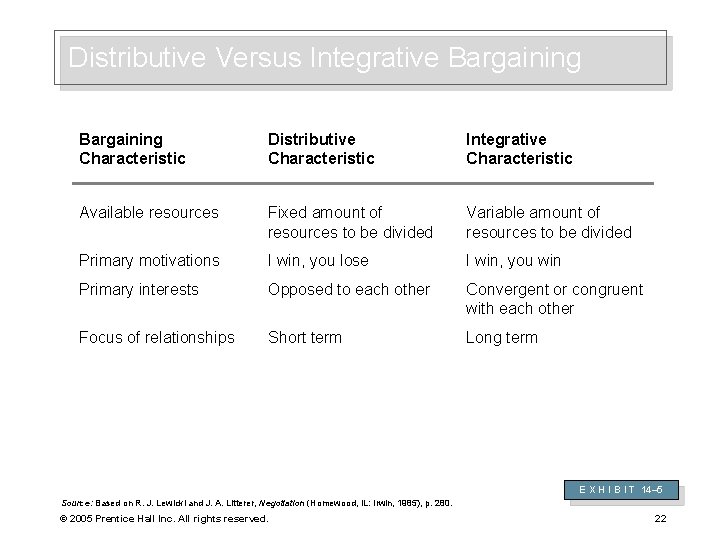

Distributive Versus Integrative Bargaining Characteristic Distributive Characteristic Integrative Characteristic Available resources Fixed amount of resources to be divided Variable amount of resources to be divided Primary motivations I win, you lose I win, you win Primary interests Opposed to each other Convergent or congruent with each other Focus of relationships Short term Long term E X H I B I T 14– 5 Source: Based on R. J. Lewicki and J. A. Litterer, Negotiation (Homewood, IL: Irwin, 1985), p. 280. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 22

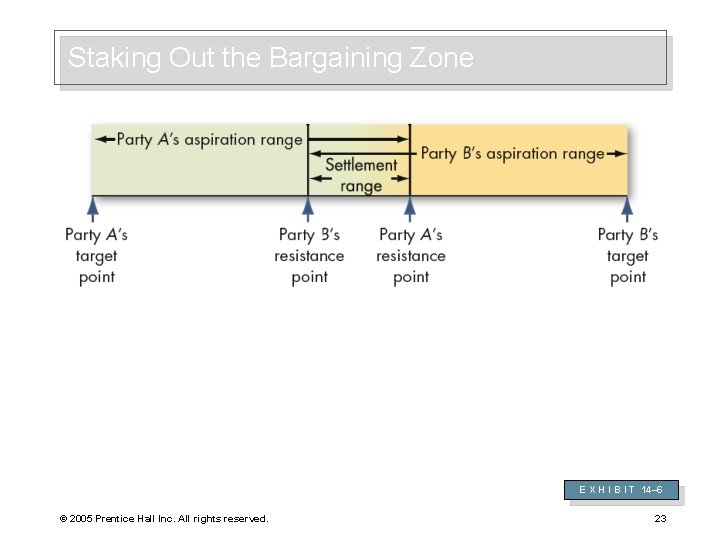

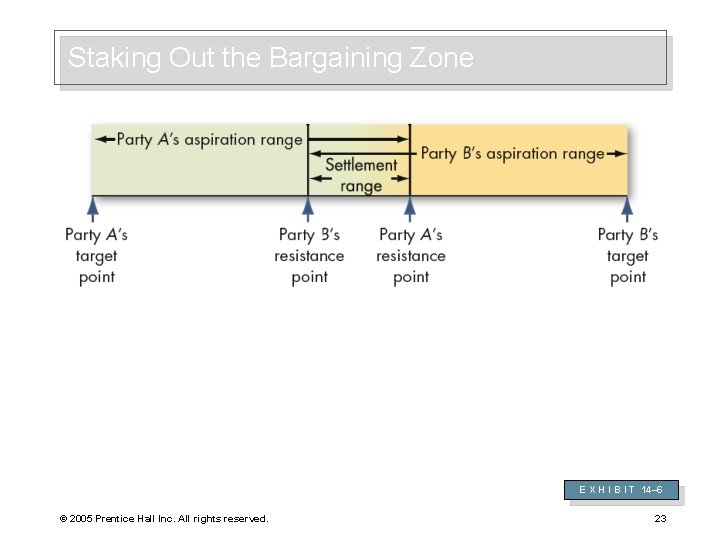

Staking Out the Bargaining Zone E X H I B I T 14– 6 © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 23

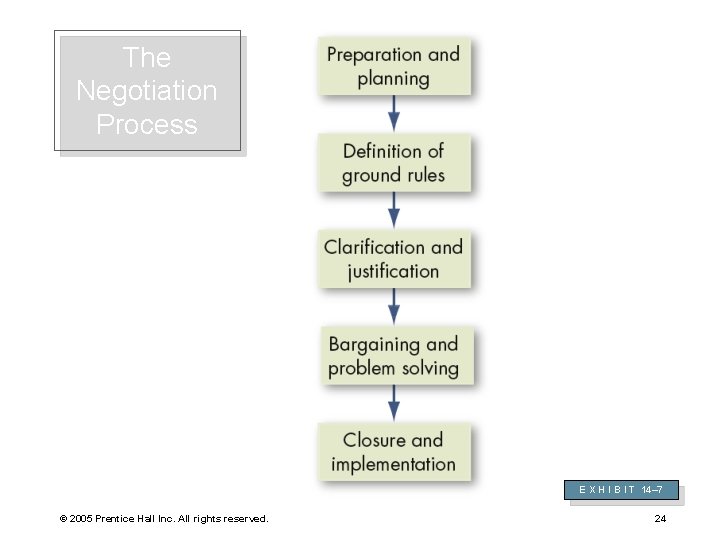

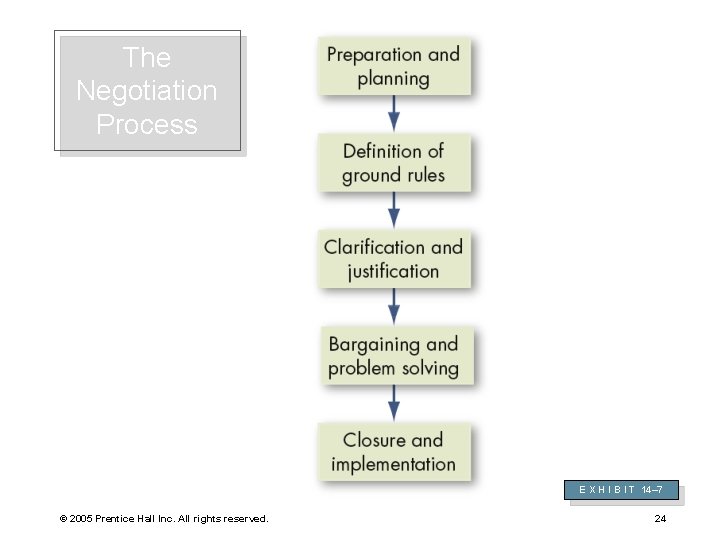

The Negotiation Process E X H I B I T 14– 7 © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 24

Issues in Negotiation Ø The Role of Personality Traits in Negotiation – Traits do not appear to have a significantly direct effect on the outcomes of either bargaining or negotiating processes. Ø Gender Differences in Negotiations – Women negotiate no differently from men, although men apparently negotiate slightly better outcomes. – Men and women with similar power bases use the same negotiating styles. – Women’s attitudes toward negotiation and their success as negotiators are less favorable than men’s. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 25

The Successful Intercultural Negotiator: Ø 1. Successful intercultural negotiators are always cognizant of the fact that people do, indeed, feel, think and behave differently, while at the same time, they are equally logical and rational. Ø Effective intercultural negotiators are sensitive to the fact that each person perceives, discovers, and constructs reality -- the internal and external world – in varied yet meaningful ways. Ø They understand that difference is not threatening; indeed, it is positive, so long as the differences are managed properly. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 26

Why American Managers Might Have Trouble in Cross. Cultural Negotiations § § § Italians, Germans, and French don’t soften up executives with praise before they criticize. Americans do, and to many Europeans this seems manipulative. Israelis, accustomed to fast -paced meetings, have no patience for American small talk. British executives often complain that their U. S. counterparts chatter too much. Indian executives are used to interrupting one another. When Americans listen without asking for clarification or posing questions, Indians can feel the Americans aren’t paying attention. Americans often mix their business and personal lives. They think nothing, for instance, about asking a colleague a question like, “How was your weekend? ” In many cultures such a question is seen as intrusive because business and private lives are totally compartmentalized. E X H I B I T 14– 8 Source: Adapted from L. Khosla, “You Say Tomato, ” Forbes, May 21, 2001, p. 36. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 27

HOW TO NEGOTIATE WITH THAI EXECUTIVES Donald W. Hendon, Dillard University of Louisiana Ø Thai negotiators expect to entertain you and to be entertained by you in return. In fact, quite often your initial meeting with your Thai negotiating counterparts may be over lunch or drinks, so that they can get to know you. However, do not expect to discuss business over lunch. To entertain a small group, it is best to take them to a western restaurant in a five-star hotel. Arrange a buffet supper for a large group. Unlike in the Middle East, always include Thai wives in your invitation. Ø Negotiating is both a social and business function in Thailand. Ø As stated above, Thai business and government executives are very formal in their dress. The better dressed one is, the more successful one is—that is how Thais think. Ø http: //marketing. byu. edu/htmlpages/ccrs/proceedings 99/he ndon. htm © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 28

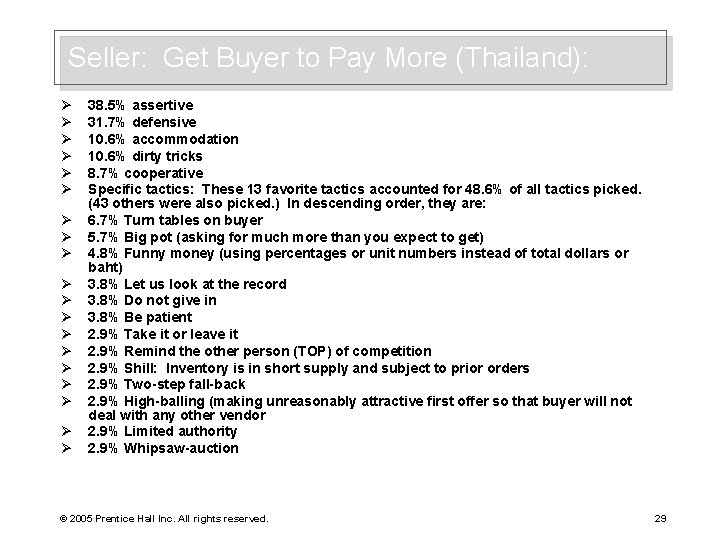

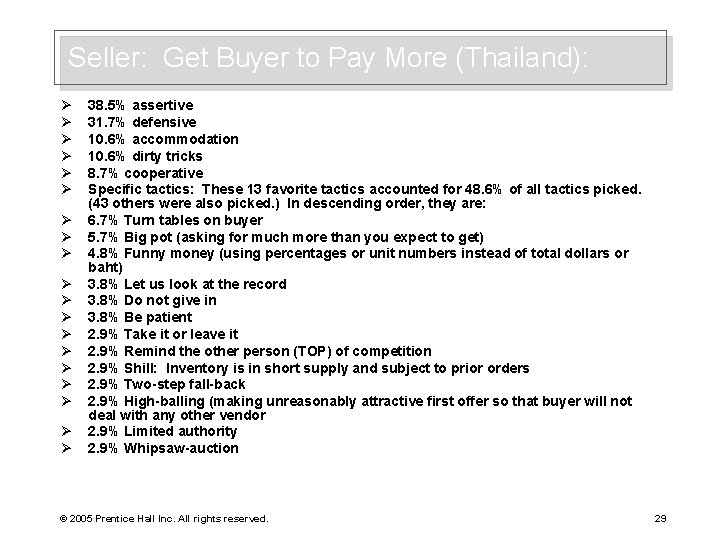

Seller: Get Buyer to Pay More (Thailand): Ø Ø Ø Ø Ø 38. 5% assertive 31. 7% defensive 10. 6% accommodation 10. 6% dirty tricks 8. 7% cooperative Specific tactics: These 13 favorite tactics accounted for 48. 6% of all tactics picked. (43 others were also picked. ) In descending order, they are: 6. 7% Turn tables on buyer 5. 7% Big pot (asking for much more than you expect to get) 4. 8% Funny money (using percentages or unit numbers instead of total dollars or baht) 3. 8% Let us look at the record 3. 8% Do not give in 3. 8% Be patient 2. 9% Take it or leave it 2. 9% Remind the other person (TOP) of competition 2. 9% Shill: Inventory is in short supply and subject to prior orders 2. 9% Two-step fall-back 2. 9% High-balling (making unreasonably attractive first offer so that buyer will not deal with any other vendor 2. 9% Limited authority 2. 9% Whipsaw-auction © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 29

Research Findings on Thai Negotiatiors…Dirty Tricks? Ø Thai sellers are significantly less aggressive than American sellers (p =. 05), but there was no significant difference between American and Thai buyers. Note also that Thai sellers use dirty tricks 10. 6% of the time, while Thai buyers use them 16. 8% of the time. The author has given this “favorite tactics used in 11 situation” exercise in 26 nations, and only Indonesians, Filipinos, and Malaysians use dirty tricks more often than Thais. Australians, Kiwis, and Canadians use dirty tricks the least. Both Thai sellers and buyers use a significantly greater amount of dirty tricks than do American sellers and buyers (p =. 05). And while Thai buyers are significantly less accommodating and cooperative than American buyers (p =. 05), there is no significant difference between American and Thai sellers in their choice of accommodation and cooperative tactics. Neither was there a significant difference between Americans and Thais in defensive tactics (both sellers and buyers). Ø © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 30

Five Intercultural Negotiation Skills: Ø Five Intercultural Negotiation Skills: 1. EMPATHY – To be able to see the world as other people see it. To understand the behavior of others from their perspectives. Ø 2. ABILITY TO DEMONSTRATE ADVANTAGES of what one proposes so that counterparts in the negotiation will be willing to change their positions. Ø 3. ABILITY TO MANAGE STRESS AND COPE WITH AMBIGUITY as well as unpredictable demands. Ø 4. ABILITY TO EXPRESS ONE’S OWN IDEAS in ways that the people with whom one negotiates will be able to objectively and fully understand the objectives and intentions at stake. Ø 5. SENSITIVITY to the cultural background of others along with an ability to adjust one’s objectives and intentions in accordance with existing constraints and limitations. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 31

Eight Mistakes to Avoid in Intercultural Negotiation: Ø 1. Avoid looking at everything from your own definition of what is “rational, ” “logical” and “scientific. ” Ø 2. Avoid pressuring the other party with a point that he/she is not readily prepared to accept; wait for a more favorable time. Ø 3. Avoid looking at issues from the narrow perspective of selfinterest. Ø 4. Avoid asking for concessions or compromised which are politically or culturally sensitive; you will not succeed with this kind of approach. Ø 5. Avoid adhering to your agenda if the other party appears to have a different set of priorities. Ø 6. Avoid speaking in jargon (i. e. using colloquialisms), which can confuse the other party and even create a feeling of mistrust. Ø 7. Avoid passing over levels of authority in manners that compromise the sensibilities of middle level officials. Ø 8. Avoid asking for a decision when you know that the other party is not able to commit. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 32

The Four Levels of Intercultural Competence: Ø Whether a person is working or living abroad for personal or professional reasons, cultural transition requires intercultural competence. Following is a brief list of the four cardinal intercultural competencies required of travelers: Ø 1. Open mindedness and an open attitude: Develop a sense of receptivity to cross-cultural learning. Ø 2. Self-Awareness and other-awareness: Identify key differences between self and others. Ø 3. Cultural Knowledge: Establish awareness in a solid base of cultural knowledge. Ø 4. Cross-cultural skills: Acquire proficiencies that build on intercultural effectiveness. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 33

Third-Party Negotiations Mediator A neutral third party who facilitates a negotiated solution by using reasoning, persuasion, and suggestions for alternatives. Arbitrator A third party to a negotiation who has the authority to dictate an agreement. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 34

Third-Party Negotiations (cont’d) Conciliator A trusted third party who provides an informal communication link between the negotiator and the opponent. Consultant An impartial third party, skilled in conflict management, who attempts to facilitate creative problem solving through communication and analysis. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 35

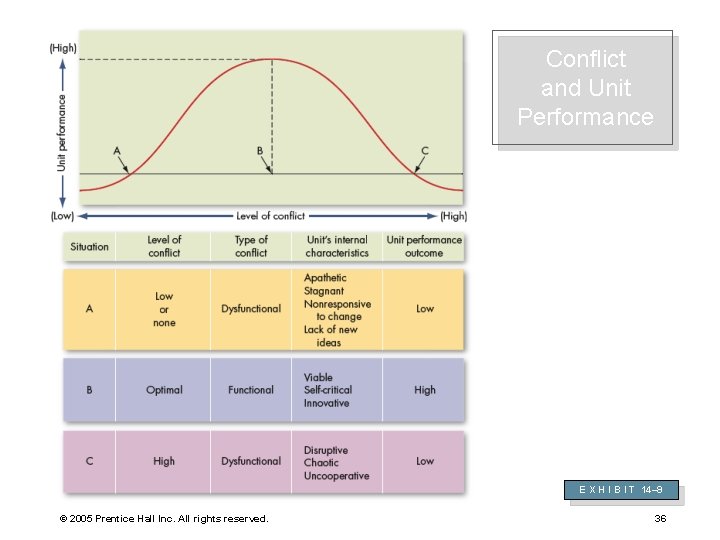

Conflict and Unit Performance E X H I B I T 14– 9 © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 36

Conflict-Handling Intention: Competition Ø When quick, decisive action is vital (in emergencies); on important issues. Ø Where unpopular actions need implementing (in cost cutting, enforcing unpopular rules, discipline). Ø On issues vital to the organization’s welfare. Ø When you know you’re right. Ø Against people who take advantage of noncompetitive behavior. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 37

Conflict-Handling Intention: Collaboration Ø To find an integrative solution when both sets of concerns are too important to be compromised. Ø When your objective is to learn. Ø To merge insights from people with different perspectives. Ø To gain commitment by incorporating concerns into a consensus. Ø To work through feelings that have interfered with a relationship. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 38

Conflict-Handling Intention: Avoidance Ø When an issue is trivial, or more important issues are pressing. Ø When you perceive no chance of satisfying your concerns. Ø When potential disruption outweighs the benefits of resolution. Ø To let people cool down and regain perspective. Ø When gathering information supersedes immediate decision. Ø When others can resolve the conflict effectively Ø When issues seem tangential or symptomatic of other issues. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 39

Conflict-Handling Intention: Accommodation Ø When you find you’re wrong and to allow a better position to be heard. Ø To learn, and to show your reasonableness. Ø When issues are more important to others than to yourself and to satisfy others and maintain cooperation. Ø To build social credits for later issues. Ø To minimize loss when outmatched and losing. Ø When harmony and stability are especially important. Ø To allow employees to develop by learning from mistakes. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 40

Conflict-Handling Intention: Compromise Ø When goals are important but not worth the effort of potential disruption of more assertive approaches. Ø When opponents with equal power are committed to mutually exclusive goals. Ø To achieve temporary settlements to complex issues. Ø To arrive at expedient solutions under time pressure. Ø As a backup when collaboration or competition is unsuccessful. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 41

Communication adaptability Ø refers to our ability to change our conflict goals and behaviors to meet the specific needs of the situation (Duran, 1985). Ø It signals our mindful awareness of the other person's perspectives, interests, and/or goals, and Ø our willingness to modify our own interests or goals to adapt to the conflict situation. Ø It can also imply behavioral flexibility in dealing with the intercultural conflict episode. By mindfully observing what is going on in the intercultural conflict situation, both parties may modify their nonverbal and verbal behavior to achieve a more synchronized interaction process. © 2005 Prentice Hall Inc. All rights reserved. 42