Analytic Ontology Lezioni 16 18 Lezione 16 51118

- Slides: 22

Analytic Ontology Lezioni 16 -18

• Lezione 16 • 5/11/18

term papers (tesine) • Marco Governatori: compare, contrast and evaluate at least 2 views about fictional objects • Michele: compare, contrast and evaluate at least 2 views on future contingents and the problem of logical fatalism • compare, contrast and evaluate at least two views on the problem of the unity of states of affairs and Bradle's regress • compare, contrast and evaluate a version of the B theory and a version of the A theory of time • compare, contrast and evaluate at least two approaches to the problem of truthmakers for presentism • compare, contrast and evaluate at least two approaches to the problem of cross-temporal relations for presentism • compare, contrast and evaluate an endurantist and a perdurantist approach to persistence • compare, contrast and evaluate at least two approaches to the problem of the ship of Theseus

(old) B-theoretic analyses • Date approach • token-reflexive approach • psychological approach

Date approach Russell 1906, Frege 1918, Goodman 1951, Quine 1960 (1) Elisabeth II is [tensed] seated on the throne; (2) Elisabeth II was seated on the throne; (3) Elisabeth II will be seated on the throne. Let's suppose they are uttered on 23/1/2007 at 12. If so, they express the propositions that we could have expressed thus: • (1 a) Elisabeth II is [tenseless] seated on the throne at 12 on 23/1/2007; • (2 a) Elisabeth II is seated on the throne at a moment that precedes 12 on 23/1/2007; • (3 a) Elisabeth II is seated on the throne at a moment that follows 12 on 23/1/2007. • • •

Token-reflexive approach • attributed to Russell in Mc. Taggart (1927), Reichenbach (1947), Williams (1951, p. 59) • (2) Elisabeth II was seated on the throne (uttered on 23/1/2007 at 12, thus producing token e) • (2 a) [Elisabeth II's being seated on the throne precedes the uttering of this token] • (2 a') /Elisabeth II's being seated on the throne precedes the uttering of e

Psychological approach • Russell in various writings (e. g. , 1915) • (2) Elisabeth II was seated on the throne (uttered on 23/1/2007 at 12, by a subject with sense-datum d in her mind) • (2 a) Elisabeth II's being seated on the throne precedes the occurrence of d • speaker's meaning hearer's meaning

• Lez. 17 • 6/11/18

tensed predication • (1) John is (tensedly) seated • This involves a tensed predication of the predicate "seated". It expresses the same proposition at different times, a proposition in which the attribute [seated] is tensedly attributed to John. • In typical cases these propositions change truth values. But some of them do not: God is (tensedly) omnipotent

Tenseless predication • (2) Garibaldi meets (tenselessly) Vittorio Emanuele II at t • This also expresses the same proposition at different times. But its truth value does not change (if t is future non-eternalists may dissent here; we shall go back to this) • (3) Garibaldi's meeting VE II is (tenselessly) earlier than the utterance of this token • A token of (3) expresses a different proposition any time it is uttered, but a proposition that does not change its truth value (the sentence type may be said to change truth value by virtue of having different tokens expressing different propositions) • If in sentences such as (3) we have "later" instead of "earlier", noneternalists may say that the truth value of the expressed proposition may change; we shall go back to this)

The problem of cognitive value • Gale (1962) • (1) the enemy is approaching. • (1 a) the enemy is approaching on July 23 2011 at noon • The proposition expressed by (1 a) does not have the same cognitive value as the one expressed by (1) and thus the two sentences do not express the same proposition

New B theory • There are tensed proposition, e. g. that the enemy is (tensedly, presently) approaching • Yet there are not in reality tensed states of affairs (Smart 1980, Mellor 1981, Oaklander 2004) • The sentinel has a true belief IFF, at the moment in which he has the belief there occurs the tenseless fact consisting of the approaching of the enemy. • It is admitted that these tensed propositions are subject to alethic change • Yet, no tensional change: we have the impression there is because our tensed beliefs keep changing (Mellor)

token-reflexivity and cognitive value: (do we need a new B theory? ) • (1/tr) the enemy's approaching is simultaneous with the utterance of this token • Q 1: Has this the appropriate cognitive value? • Q 2: Are there other problems with token-reflexivity? (Q. Smith, 1987, 1993) • Orilia and Oaklander (Topoi 2015) reply yes to Q 1 and no to Q 2 and thus repropose the old B theory in its token-reflexive version • According to Gale (the language of time, 1968), token-reflexivity implies tensedness, since for Gale a sentence is tensed if its different tokens may have different truth values • In my view the "is" of (1/tr) is tenseless. The sentence changes truth value by virtue of having different tokens expressing different propositions (which do not change in truth value)

• Lez. 18 • 7/11/18

A theory

A-theory in a song. . . • Vola il tempo lo sai che vola e va, forse non ce ne accorgiamo [sic], . . . • (Fabrizio De André, Valzer per un amore)

and presentism (in the same song) • ". . . più ancora del tempo che se va, siamo noi che ce ne andiamo"

A theory • There is an objective presentness. • accepts ontological tensism (tensed facts) and is thus often called tensed theory of time • terminological interlude: "fact" as state of affairs and as true proposition • Accepts tensional change (time passage, change in A-properties), thus it is often called dynamic theory of time (NB: this is not an obvious point in presentism) • Example: any event simultaneous to Mennea's winning step in 200 meters final race at the Olimpic games in 1980 is objectively past, whereas any event simultaneous with my saying these words is objectively present, even though it soon will lose presentness and will be past

Basic point from Relativity theory (review) • According to relativity theory there is no objective simultaneity but only simultaneity relative to a frame of reference • if whatever is simultaneous to a present event is present, there is no objective presentness • If presentness is the dividing line between past and future, there is no objective past and future, but only past and future relative to a frame of reference • Similarly, we may say, there is no objective earlier and later • Yet, if two events are time-like separated their earlier/later relation is the same in all frames of reference

Important (main? ) motivation for the A theory • (MPI) Methodological principle of innocence. (A) A theory in line with common sense and ordinary language deserves initial acceptance [innocent], (B) at least until philosophical analysis and scientific inquiry reveal its inadequacy [until proven guilty] and an alternative theory is available • W. Sellars (1962): scientific image vs. manifest image • P. Strawson (1959): revisionary vs. descriptive metaphysics • C. S. Peirce ("Issues in Pragmatism", 1905): Critical Commonsensism • G. E. Moore (1952): "A defense of common sense" • Rev. Thomas Reid (1710 -1796): common-sense realism

Methodological principle of innocence • If we apply part (A) of this to temporal ontology, it seems reasonable to attribute an ontological role to tenses, since their use is so pervasive. • Thus, it is prima facie preferable to assume that they are not a surface grammatical phenomenon, which we could renounce in describing reality. Rather, in allowing us to express tensed propositions, they witness the existence of tensed events and thus that reality is tensed • This is in line with the semantic and ontological tensism of the A theory. • However, not all versions of the A theory are equally satisfactory from this point of view, or at least they may score differently, depending on different aspects of common sense

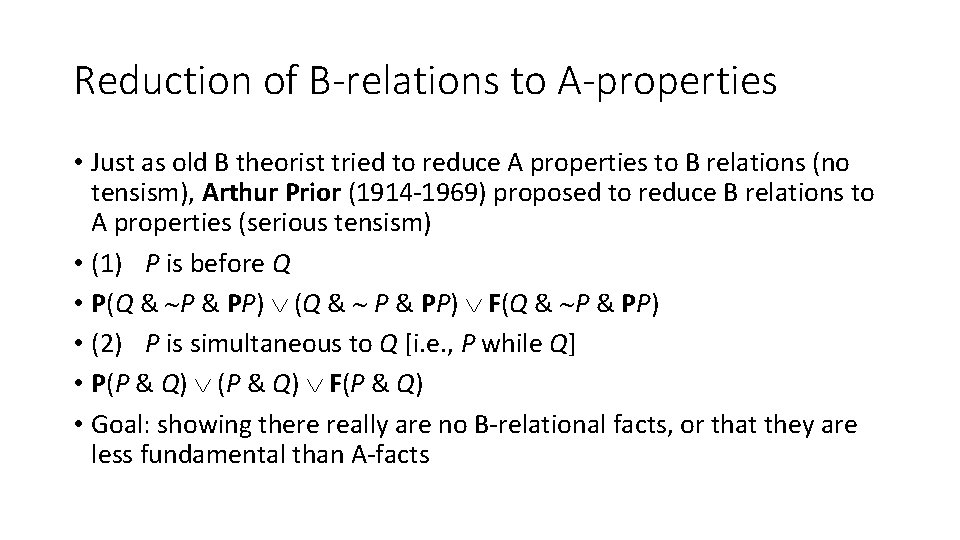

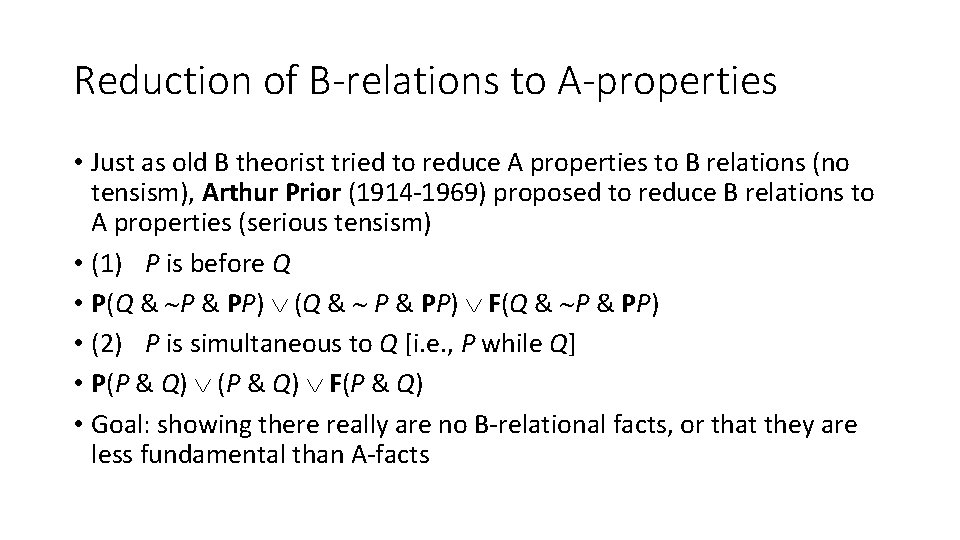

Reduction of B-relations to A-properties • Just as old B theorist tried to reduce A properties to B relations (no tensism), Arthur Prior (1914 -1969) proposed to reduce B relations to A properties (serious tensism) • (1) P is before Q • P(Q & PP) (Q & P & PP) F(Q & PP) • (2) P is simultaneous to Q [i. e. , P while Q] • P(P & Q) F(P & Q) • Goal: showing there really are no B-relational facts, or that they are less fundamental than A-facts

Liceo linguistico dolo

Liceo linguistico dolo Liceo scientifico galileo galilei dolo orario lezioni

Liceo scientifico galileo galilei dolo orario lezioni Fisica lezioni e problemi 1 soluzioni

Fisica lezioni e problemi 1 soluzioni Fisica lezioni e problemi 1 soluzioni

Fisica lezioni e problemi 1 soluzioni Principio di pascal

Principio di pascal Sovrapposizione delle onde

Sovrapposizione delle onde Liceomontanari.it

Liceomontanari.it Lezioni di tecnica delle costruzioni

Lezioni di tecnica delle costruzioni Fisica: lezioni e problemi 2 soluzioni

Fisica: lezioni e problemi 2 soluzioni Lezioni partecipate

Lezioni partecipate Sistema ridotto in forma normale

Sistema ridotto in forma normale Lezioni online unich

Lezioni online unich Baricentro

Baricentro Variabilità statistica

Variabilità statistica Dott armonico giuseppe

Dott armonico giuseppe Biochimica lezioni

Biochimica lezioni Lezione 7

Lezione 7 Lezione simulata

Lezione simulata Sostenibilit

Sostenibilit Esempi jigsaw

Esempi jigsaw La lezione della farfalla libro

La lezione della farfalla libro Esempio di lezione clil diritto

Esempio di lezione clil diritto Lezione masculine or feminine

Lezione masculine or feminine