Analytic Ontology Lezioni 7 9 Lezione 7 151018

- Slides: 32

Analytic Ontology Lezioni 7 -9

• Lezione 7 • 15/10/18

• Program for this week: • universalism vs tropism • Attempts to solve the problem of unity • (Relations and relational order)

Readings for next week • Mc. Taggart, The unreality of time • Loux, Ch. 7, up to p. 212

Let's take stock • We saw that in discussing time we typically consider events (states of affairs, facts), the entities that occur at times; we may say they are the temporal entities par excellence • We saw that a typical way to conceive of events is by viewing them as objects' exemplifying (at times) properties or relations, UNDERSTOOD AS UNIVERSALS. • We saw that this leads to the problem of unity and to Bradley's regress, which many see as problematic • Questions: are we sure we really need to postulate events, with properties and relations so understood?

Preview • Let's look at the data • let's consider the main alternatives: universalism ("metaphysical realism" in Loux) vs. tropism (a version of nominalism) • The problem of unity can hardly be avoided: let's go back to the options (outlined in the hand-out of last week, in the part that we did not look at) • Time permitting, we shall consider the special problems posed by relations • Next week we shall go back to the philosophy of time: Mc. Taggart

Universalism vs. tropism

Protophilosophy • The most important and difficult task of collecting the relevant shared pretheoretical data regarding a certain problem (or cluster of problems) and presenting them in a neutral (pretheoretical) terminology (as far as possible). • Hector-Neri Castañeda

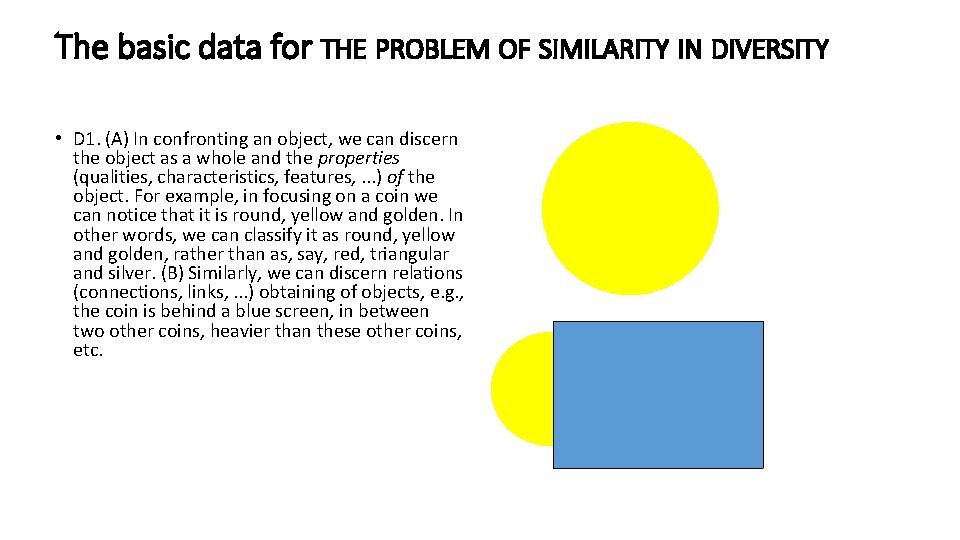

The basic data for THE PROBLEM OF SIMILARITY IN DIVERSITY • D 1. (A) In confronting an object, we can discern the object as a whole and the properties (qualities, characteristics, features, . . . ) of the object. For example, in focusing on a coin we can notice that it is round, yellow and golden. In other words, we can classify it as round, yellow and golden, rather than as, say, red, triangular and silver. (B) Similarly, we can discern relations (connections, links, . . . ) obtaining of objects, e. g. , the coin is behind a blue screen, in between two other coins, heavier than these other coins, etc.

"similarity or attribute agreement" (Loux, p. 19) • D 2. (A) In confronting two or more objects, say two coins, we may notice that they, though numerically distinct, “share something” or “have something in common”. More precisely, we are tempted to say, they share some (or perhaps all) of their characteristics, some (all) of their characteristics are similar or even the “same”. This compels us to classify both as, e. g. , yellow or round and to use one general term, “yellow” or “round” for both. (B) Similarly, we may notice that two (three, . . . ) objects stand in the “same” relation as two (three, . . . ) other objects, e. g. , the coin is on the table just as the book is on the desk.

Allow for a neutral (pre-theoretical) use of this terminology • Given that a property P is of an object x, x exemplifies (instantiates, has) P and thus there is a state of affairs or fact or event Px, e. g. , Gordon's being white, in short, Wg. • Similarly, given that relation R relates x and y, R is exemplified by x and y (taken together, in the given order) and there is the state of affairs Rxy. • We may use a convention to make cleare we are talking of events (states of affairs, facts): • /Gordon is white, /Wg, *Gordon is white*, *Wg*

Type I PRPs vs. Type II PRPs • - It seems appropriate to distinguish between states of affairs (type II propositions) and propositions (type II propositions). “Gordon is white” expresses as meaning a true proposition, [Wg], corresponding to the state of affairs /Wg. “Gordon is black” expresses a true proposition, [Bg], corresponding to no state of affairs. • - Similarly, we may want to distinguish between the type I properties or relations (“concepts”) [round], [above], [unicorn] and the type II properties or relations (qualities, connections), /round, /above • George Bealer

Questions! • - non-obtaining states of affairs? • - non-exemplified qualities and connections?

Roles for states of affairs • - Truthmaking: "Obama is black" is true because Obama is black, is made true by Obama's being black [Loux (p. 25, "phenomenon of subject predicate discourse") • - Causation: John's screaming caused Mary's awakening • - Contents of experience: we see that the table is white • We may say that states of affairs, as pre-theoretically understood, are whatever entities that fulfill these roles ("universalist" states of affairs? , tropes? )

Symphilosophy and diaphilosophy • - Construction of philosophical theories that account for the collected data • - Comparison of competing philosophical theories

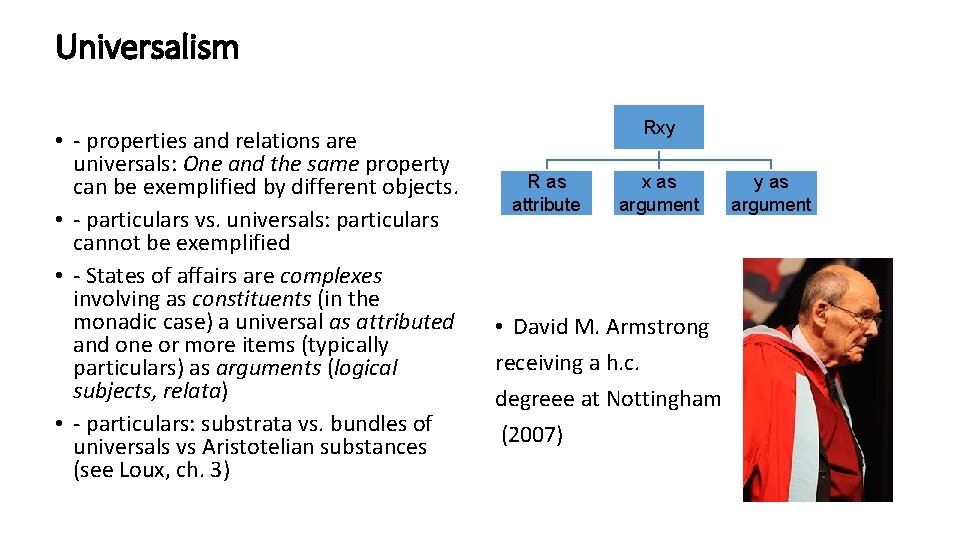

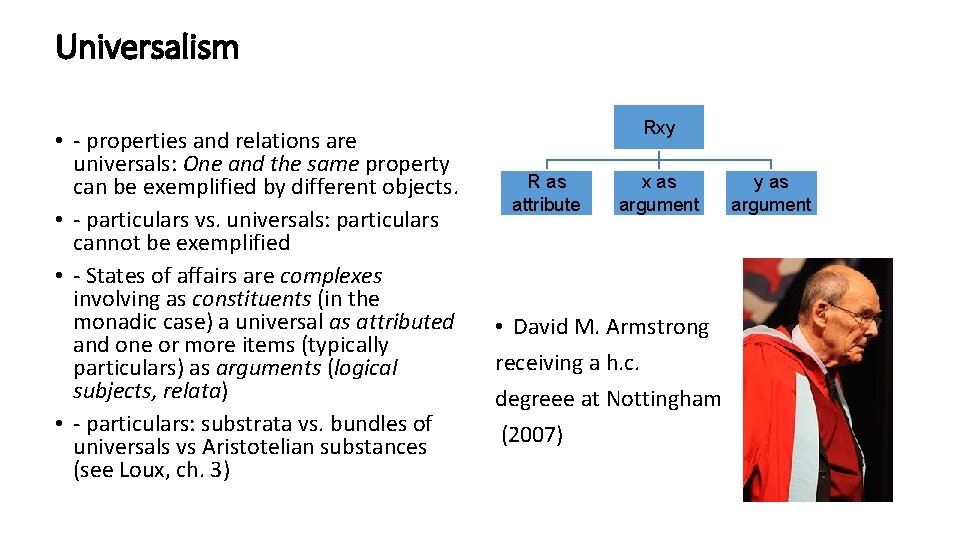

Universalism • - properties and relations are universals: One and the same property can be exemplified by different objects. • - particulars vs. universals: particulars cannot be exemplified • - States of affairs are complexes involving as constituents (in the monadic case) a universal as attributed and one or more items (typically particulars) as arguments (logical subjects, relata) • - particulars: substrata vs. bundles of universals vs Aristotelian substances (see Loux, ch. 3) Rxy R as attribute x as argument • David M. Armstrong receiving a h. c. degreee at Nottingham (2007) y as argument

Tropism • D. C. Williams (1953), Peter Simons (Leeds), Anna-sofia Maurin (Goeteborg) • Properties (and relations) are tropes (abstract particulars): a property (qua trope) can be exemplified by only one object, although two properties (of two objects) can resemble each other to varying degrees. • ordinary (concrete) particulars (apples and tables) vs. abstract particulars • State of affairs are tropes: they can fulfill the 3 roles, truthmakers, causal relata, contents of perception • Better account of the problem of unity? We shall see • ordinary particulars as bundles of tropes vs. ordinary particulars as substrates

• Lezione 8 • 16/10/18

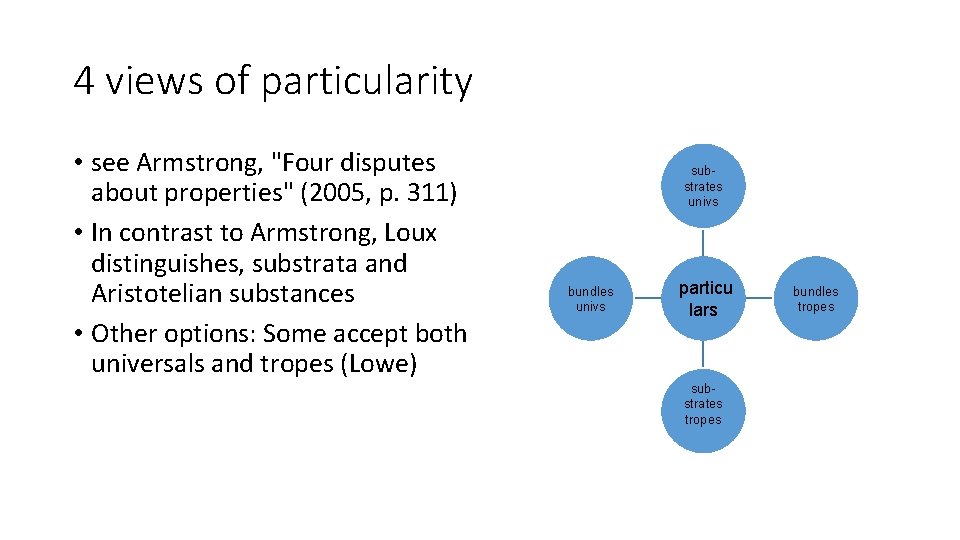

4 views of particularity • see Armstrong, "Four disputes about properties" (2005, p. 311) • In contrast to Armstrong, Loux distinguishes, substrata and Aristotelian substances • Other options: Some accept both universals and tropes (Lowe) substrates univs bundles univs particu lars substrates tropes bundles tropes

trope theory and Bradley's regress • (1) trope f and trope g are perfectly similar • Here the tropist would say that the relation is internal: it is not possible that f and g exist without being perfectly similar (in contrast, e. g. , /on is external: the computer is on the desk, but they could have existed without the former being on the latter) • (2) trope a and trope b are compresent • Here the story is more complicated, because the relation is not internal. The two tropes could have existed without being compresent (otherwise there would not be contingency in the world) • Bradley's regress: c 1(a, b), c 2(c 1, a, b), . . .

Maurin on compresence • Compresence tropes depend for their existence on the tropes they relate; such tropes on the other hand, could exist without being related by them (see her SEP entry on tropes) • Actual world: {|c 1, f, g, h, . . . |}, . . . • Possible world: {|c 2, f, . . . |}, {|c 3, g, . . . |}, {|c 4, h, . . . |}, . . . • The compresence of f, g, h, . . . is explained by the existence of c 1: if c 1 had not existed, f, g, h would not have been compresent • Problem. . .

• Lezione 8 • 17/10/18

the term "trope" • From the Winter 2011 ed. of SEP, by John Bacon: The most compelling advocate of such objects in our time has been D. C. Williams (1953), who is responsible for the regrettable term trope. It has nothing to do with figures of speech in rhetoric, Leitmotive in music, or tropisms in plants. Williams coined it as a sort of philosophical joke: Santayana, he says, had employed ‘trope’ pointlessly for ‘essence of an occurrence’. Williams would go him one better and press it into service for ‘occurrence of an essence’ (1953: 78). • Da diz. Treccani: tropo [dal lat. tropus, gr. τρόπος; affine a τρέπω «volgere; adoperare con altro uso» ]. – 1. Metafora, e in genere traslato, come figura retorica di carattere semantico

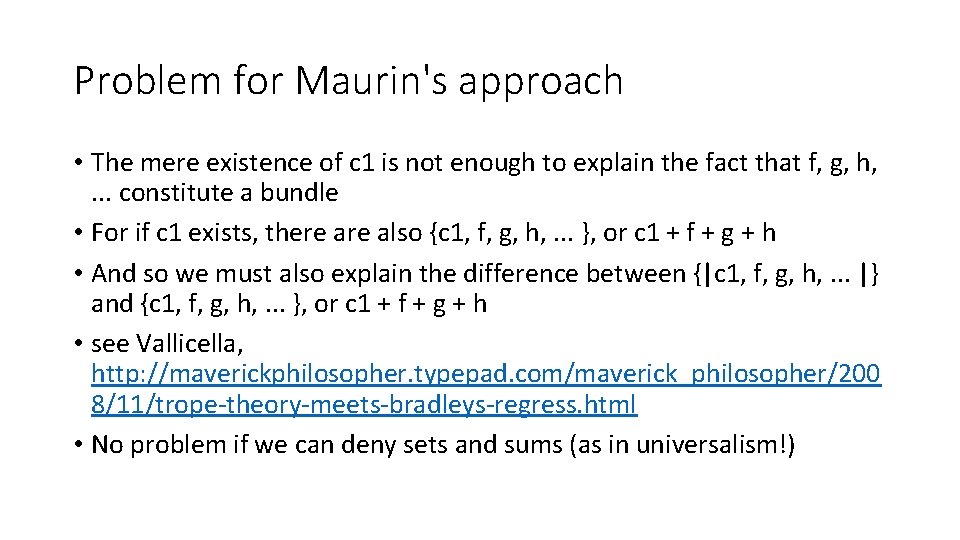

Problem for Maurin's approach • The mere existence of c 1 is not enough to explain the fact that f, g, h, . . . constitute a bundle • For if c 1 exists, there also {c 1, f, g, h, . . . }, or c 1 + f + g + h • And so we must also explain the difference between {|c 1, f, g, h, . . . |} and {c 1, f, g, h, . . . }, or c 1 + f + g + h • see Vallicella, http: //maverickphilosopher. typepad. com/maverick_philosopher/200 8/11/trope-theory-meets-bradleys-regress. html • No problem if we can deny sets and sums (as in universalism!)

Back to Universalism and Bradley's regress

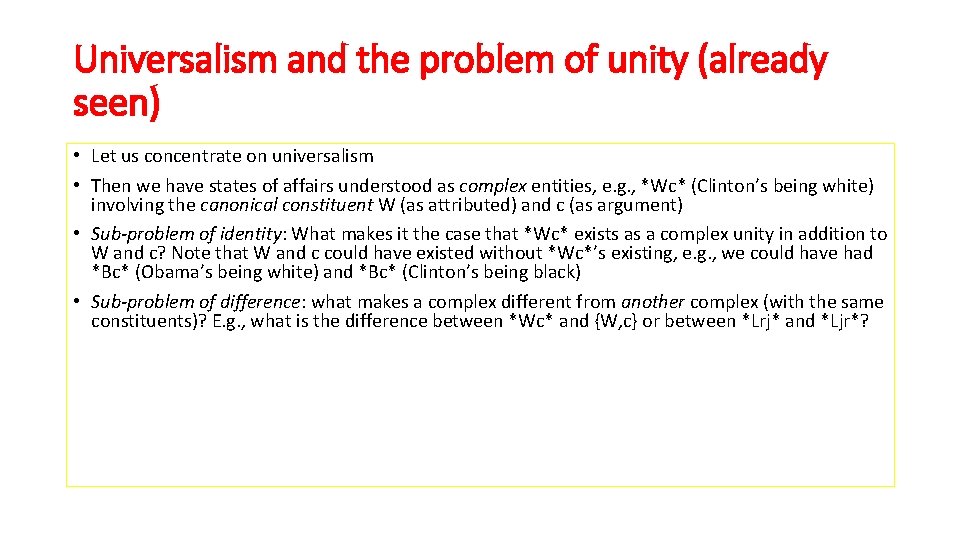

Universalism and the problem of unity (already seen) • Let us concentrate on universalism • Then we have states of affairs understood as complex entities, e. g. , *Wc* (Clinton’s being white) involving the canonical constituent W (as attributed) and c (as argument) • Sub-problem of identity: What makes it the case that *Wc* exists as a complex unity in addition to W and c? Note that W and c could have existed without *Wc*’s existing, e. g. , we could have had *Bc* (Obama’s being white) and *Bc* (Clinton’s being black) • Sub-problem of difference: what makes a complex different from another complex (with the same constituents)? E. g. , what is the difference between *Wc* and {W, c} or between *Lrj* and *Ljr*?

A quotation from Bradley (already seen) • We may take the familiar instance of a lump of sugar. This is a thing, and it has properties. . It is, for example, white, and hard, and sweet; but what the is can really mean seems doubtful. Sugar is obviously not mere whiteness, mere hardness, and mere sweetness; for its reality lies somehow in its unity. . The word to use, when we are pressed, should not be is, but only has. The whole question is evidently as to the meaning of has; and, apart from metaphors not taken seriously, there appears really to be no answer. . . [A possible answer is: ] 'There is a[n independently real] relation C, in which A [a thing] and B [a property] stand; and it appears with both of them. ' But here again we have made no progress. The relation C has been admitted different from A and B, and no longer is predicated of them. Something, however, seems to be said of this relation C, and said, again, of A and B. And this something is not to be the ascription of one to the other. If so, it would appear to be another relation D, in which C, on one side, and on the other side, A and B, stand. But such a makeshift leads at once to an infinite process. The new relation D can be predicated in no way of C, or of A and B; and hence we must have recourse to a fresh relation, E, which comes between D and whatever we had before. But this must lead to another, F; and so on, indefinitely. Thus the problem is not solved by taking relations as independently real. (A&R, 1893, Ch. 2, pp. 16 -18)

Forerunners (already seen) • Articulation of a similar regress found in Aristotle (Metaphysics Zeta (Book VII, Chapter 17, Bekker 1041 b 10 -30): discussion of part/whole), the Scholastic thinkers Abelard, Avicenna, Scotus, Ockam Buridan, Gregory of Riminy, Suarez and in Leibniz (see Gaskin). Compare also to the 3 d man problem in Plato and Aristotle.

Bradley sequences and Bradley’s regress(es) (already seen) • Fa, E 2 Fa, E 3 Fa, . . . • Internalist regress: Fa = E 2 Fa = E 3 E 2 Fa =. . The idea is to postulate as new constituent in Fa a relation E 2 linking F and a in order to account for the unity of the complex Fa. This however triggers a new demand for E 3 and so on (Russell POM, Hochberg 1989, Dodd 1999). • Externalist regress: Fa E 2 Fa E 3 E 2 Fa . . The idea is that the very existence of Fa requires that a relation E 2 relates F and a in such a way that there is a new fact E 2 Fa, and so on (Loux 1998). • See Orilia 2006, 2007.

• A "NO EXPLANATION" reply to the request for explanation. . .

The Brute Fact Approach (BFA) • The unity of a state of affairs is a brute (ontological) fact, i. e. , there is no explanation for it (Van Inwagen? ). • It can be pursued as long as we don’t admit different complexes with the same constituents. • For if, e. g. , *Fa*, F+a, {F, a} have the same constituents, there must be something other than constituents that account for their difference (sub-problem 2). • And why can’t this something be appealed to provide the requested explanation (for sub-problem 1)? • We may be able to deny that sets (Russell’s no-class theory of classes) and unrestricted mereological sum exist. • And we can perhaps analyze the difference of *Rxy* and *Ryx* in terms of constituents. But how far can this strategy be pursued?

Unrestricted mereological sums • Socrates’ nose + Heidegger’s right arm? ? ?

Vie metaboliche cicliche

Vie metaboliche cicliche Liceo scientifico galileo galilei dolo orario lezioni

Liceo scientifico galileo galilei dolo orario lezioni Galileo galilei dolo

Galileo galilei dolo Accelerazione negativa

Accelerazione negativa Fisica lezioni e problemi soluzioni

Fisica lezioni e problemi soluzioni Legge di stevino mappa concettuale

Legge di stevino mappa concettuale Fisica

Fisica Istituto montanari verona

Istituto montanari verona Lezioni di tecnica delle costruzioni

Lezioni di tecnica delle costruzioni Scomposizione forze piano inclinato

Scomposizione forze piano inclinato Lezioni partecipate

Lezioni partecipate Lezioni di rocco

Lezioni di rocco Lezioni online unich

Lezioni online unich Zanichelli

Zanichelli Elementi di statistica descrittiva

Elementi di statistica descrittiva Formula spostamento

Formula spostamento Lezione 7

Lezione 7 Fasi di una lezione simulata

Fasi di una lezione simulata Sostenibilit

Sostenibilit Esempio pratico di jigsaw

Esempio pratico di jigsaw La lezione della farfalla

La lezione della farfalla Esempio di lezione clil diritto

Esempio di lezione clil diritto Italian plural articles

Italian plural articles L'esperienza delle cose moderne e la lezione delle antique

L'esperienza delle cose moderne e la lezione delle antique L'esperienza delle cose moderne

L'esperienza delle cose moderne Schema .org

Schema .org Protege owl tutorial

Protege owl tutorial Ontology versus epistemology

Ontology versus epistemology Ontology schema

Ontology schema Business model ontology

Business model ontology Gene ontology

Gene ontology Ontology vs epistemology vs methodology

Ontology vs epistemology vs methodology Metu class

Metu class