The Unique Games Conjecture with Entangled Provers is

![Example: the CHSH game • The CHSH game: [Clauser. Horne. Shimony. Holt 69] – Example: the CHSH game • The CHSH game: [Clauser. Horne. Shimony. Holt 69] –](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/446350e7a9ced9c2a8c64b3829485650/image-4.jpg)

![Games with Entangled Provers • The only other known result is by [Masanes 05] Games with Entangled Provers • The only other known result is by [Masanes 05]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/446350e7a9ced9c2a8c64b3829485650/image-12.jpg)

- Slides: 27

The Unique Games Conjecture with Entangled Provers is False Julia Kempe Tel Aviv University Oded Regev Tel Aviv University Ben Toner CWI, Amsterdam

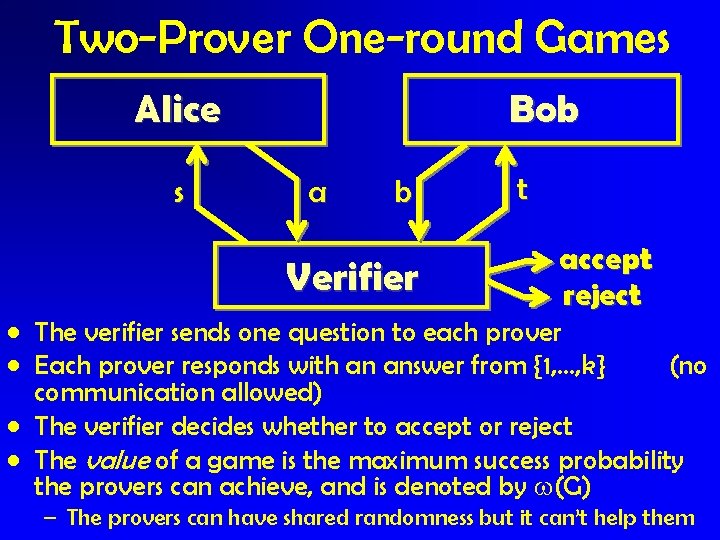

Two-Prover One-round Games Alice s Bob a b Verifier t accept reject • The verifier sends one question to each prover • Each prover responds with an answer from {1, …, k} (no communication allowed) • The verifier decides whether to accept or reject • The value of a game is the maximum success probability the provers can achieve, and is denoted by (G) – The provers can have shared randomness but it can’t help them

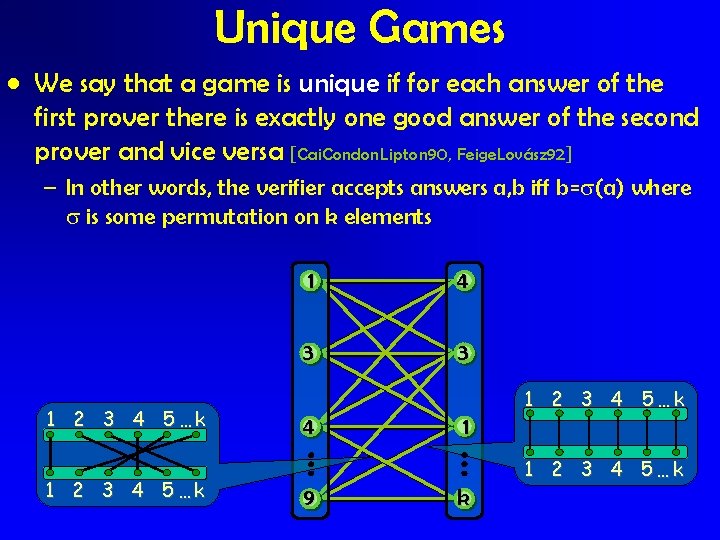

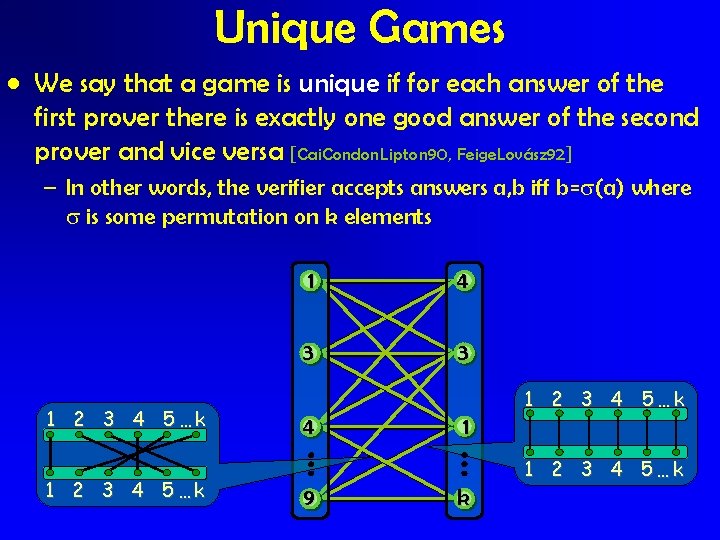

Unique Games • We say that a game is unique if for each answer of the first prover there is exactly one good answer of the second prover and vice versa [Cai. Condon. Lipton 90, Feige. Lovász 92] – In other words, the verifier accepts answers a, b iff b= (a) where is some permutation on k elements 1 2 3 4 5…k 1 4 3 3 4 1 1 2 3 4 5…k 9 k

![Example the CHSH game The CHSH game Clauser Horne Shimony Holt 69 Example: the CHSH game • The CHSH game: [Clauser. Horne. Shimony. Holt 69] –](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/446350e7a9ced9c2a8c64b3829485650/image-4.jpg)

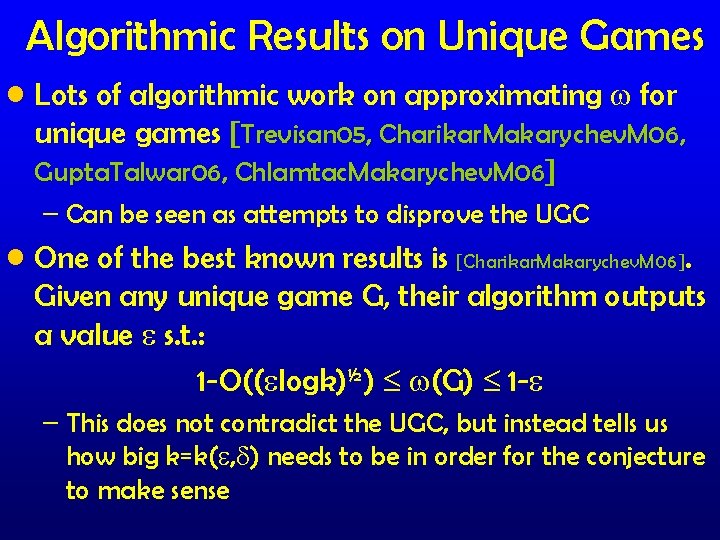

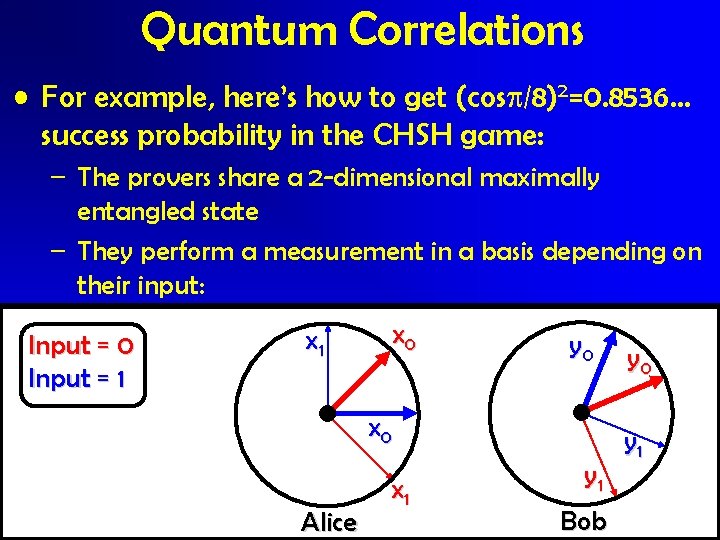

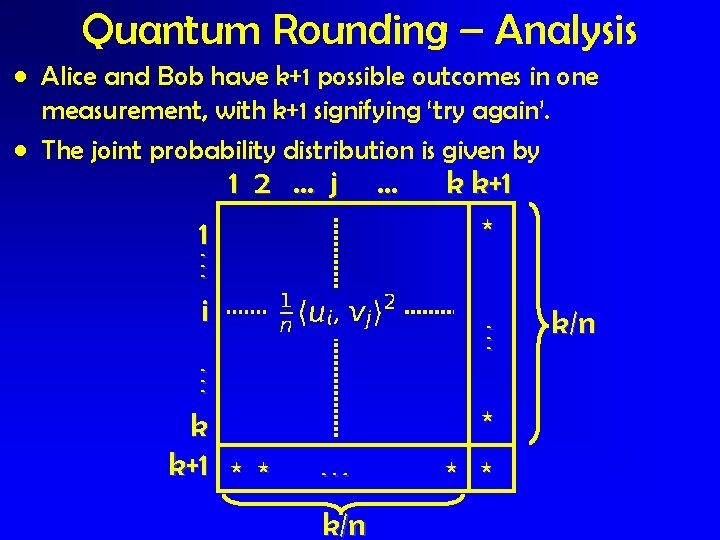

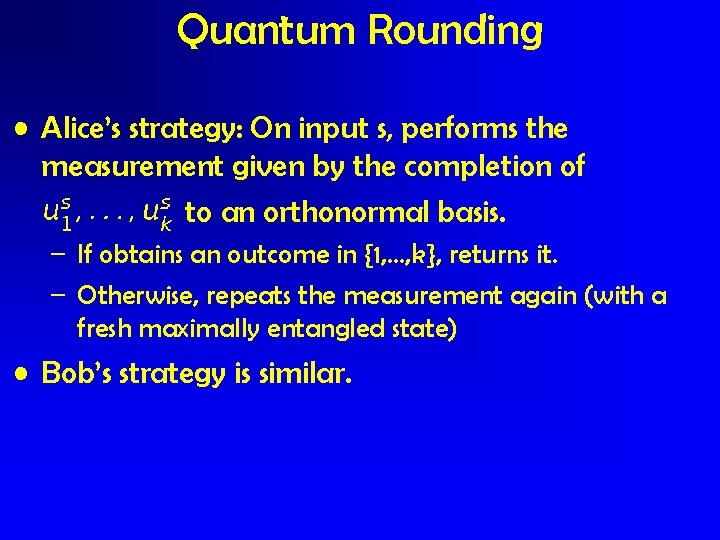

Example: the CHSH game • The CHSH game: [Clauser. Horne. Shimony. Holt 69] – The verifier sends a random bit to each prover – Each prover responds with a bit (so k=2 here) – The verifier accepts iff the XOR of the answers is equal to the AND of the questions – Unique game 1 = 1 • The value of this game is 3/4 = 1 = ≠ 1

Unique Games Conjecture (UGC) • In 2002, Khot conjectured that estimating the value of unique games is also hard: • Conjecture: [Khot 02] , >0 k such that it is NP-hard to determine whether a given unique game G with answer size k has (G) 1 - or (G)< Remarks: – It is crucial that >0 since otherwise easy – The PCP theorem + parallel repetition shows this without the “unique” requirement

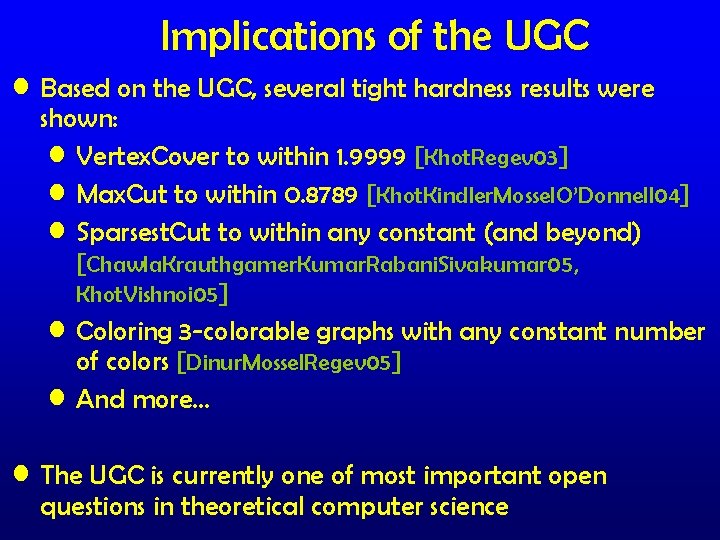

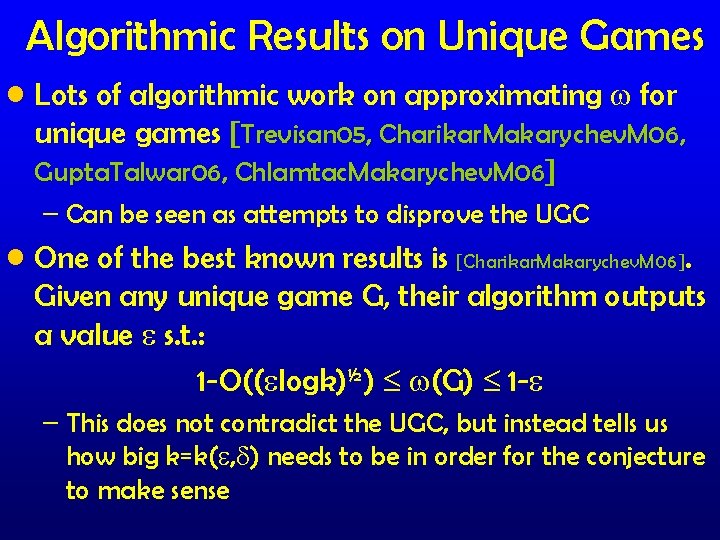

Implications of the UGC • Based on the UGC, several tight hardness results were shown: • Vertex. Cover to within 1. 9999 [Khot. Regev 03] • Max. Cut to within 0. 8789 [Khot. Kindler. Mossel. O’Donnell 04] • Sparsest. Cut to within any constant (and beyond) [Chawla. Krauthgamer. Kumar. Rabani. Sivakumar 05, Khot. Vishnoi 05] • Coloring 3 -colorable graphs with any constant number of colors [Dinur. Mossel. Regev 05] • And more… • The UGC is currently one of most important open questions in theoretical computer science

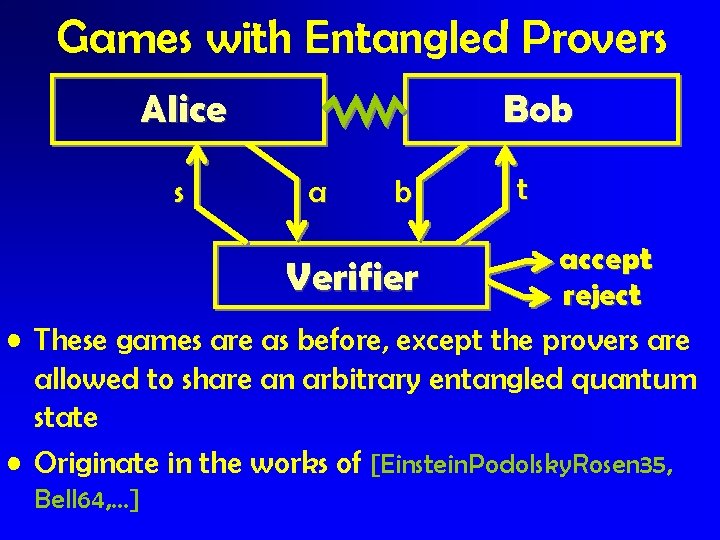

Algorithmic Results on Unique Games • Lots of algorithmic work on approximating for unique games [Trevisan 05, Charikar. Makarychev. M 06, Gupta. Talwar 06, Chlamtac. Makarychev. M 06] – Can be seen as attempts to disprove the UGC • One of the best known results is [Charikar. Makarychev. M 06]. Given any unique game G, their algorithm outputs a value s. t. : 1 -O(( logk)½) (G) 1 - – This does not contradict the UGC, but instead tells us how big k=k( , ) needs to be in order for the conjecture to make sense

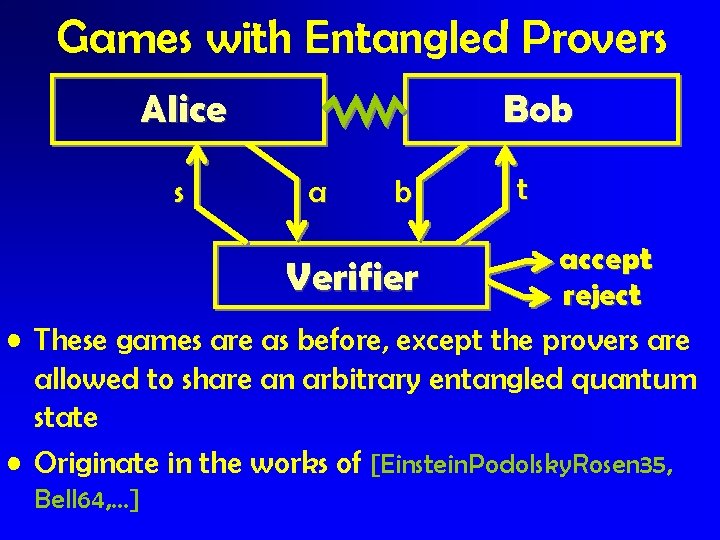

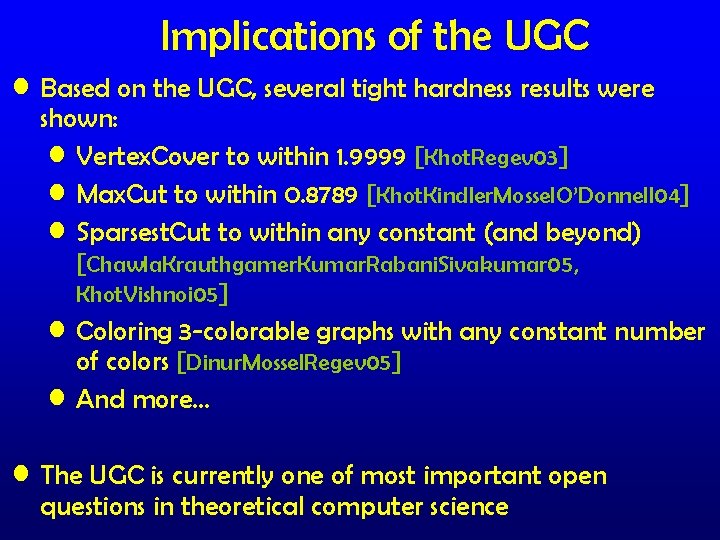

Games with Entangled Provers Alice s Bob a b t accept Verifier reject • These games are as before, except the provers are allowed to share an arbitrary entangled quantum state • Originate in the works of [Einstein. Podolsky. Rosen 35, Bell 64, …]

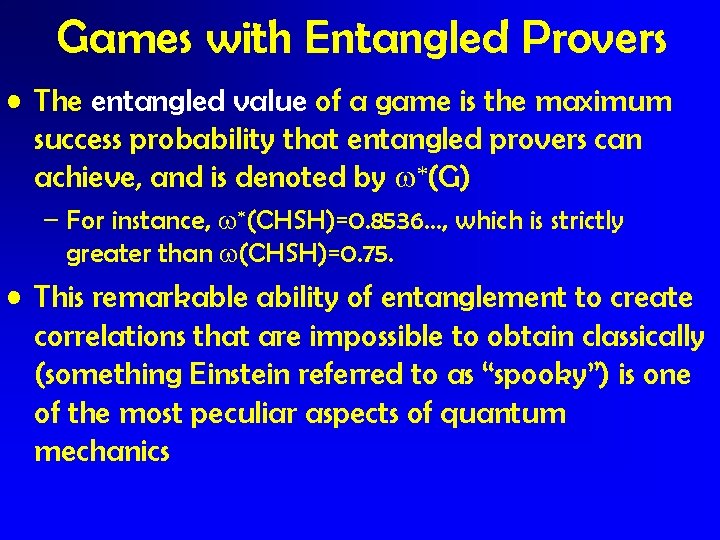

Games with Entangled Provers • The entangled value of a game is the maximum success probability that entangled provers can achieve, and is denoted by *(G) – For instance, *(CHSH)=0. 8536…, which is strictly greater than (CHSH)=0. 75. • This remarkable ability of entanglement to create correlations that are impossible to obtain classically (something Einstein referred to as “spooky”) is one of the most peculiar aspects of quantum mechanics

Games with Entangled Provers • Why study this model? – It was here first – If we ever want to ‘really’ use proof systems, then there is no physical way to guarantee that the provers don’t share entanglement – It might give us new insight on (non-entangled) games • Despite considerable work, our understanding of this model is still quite limited

Games with Entangled Provers • One of most important results is that of [Tsirelson 80] who showed that for the special case of unique games with k=2, the entangled value is given exactly by an SDP and can therefore be computed efficiently (see also [Cleve. Høyer. Toner. Watrous 04]) – This is in contrast to the (non-entangled) value of unique games with k=2 which is NP-hard to approximate (by Håstad’s hardness result for Max. Cut) – This SDP is used to determine that *(CHSH)=0. 8536…

![Games with Entangled Provers The only other known result is by Masanes 05 Games with Entangled Provers • The only other known result is by [Masanes 05]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/446350e7a9ced9c2a8c64b3829485650/image-12.jpg)

Games with Entangled Provers • The only other known result is by [Masanes 05] who shows how to compute * for games with two possible questions to each prover and k=2 • In all other cases, no method is known to compute or even approximate *

Our Results • Theorem: There exists an efficient algorithm that, given any unique game G outputs a value s. t. 1 -6 *(G) 1 - • This gives for the first time a way to approximate * for games with k>2 • It shows that the analogue of the UGC for entangled provers is false • Notice that our lower bound is independent of k, whereas in the non-entangled case, the lower bound is 1 -f( , k)

Techniques • We prove our main theorem in two steps: 1. We formulate an SDP relaxation of * • Surprisingly, this is essentially identical to the Feige. Lovász SDP, often used as a relaxation of 2. We then show to take a solution to the SDP and transform it into a strategy for entangled provers • We call this ‘quantum rounding’ in analogy with the rounding technique used in SDPs

The Proof

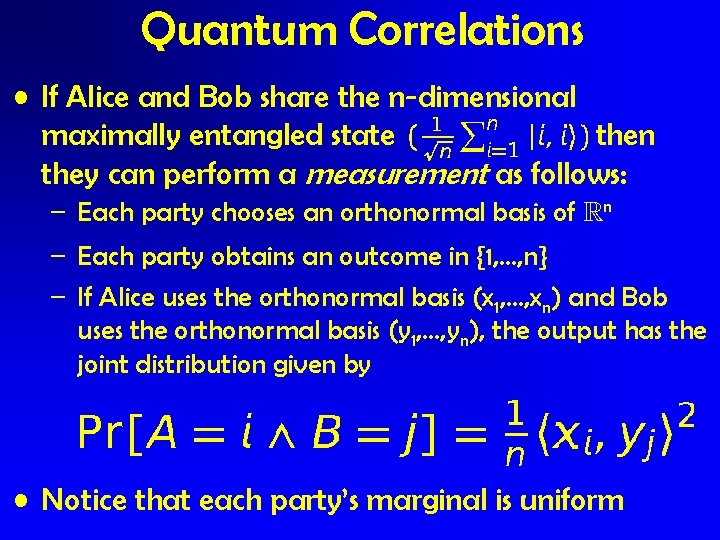

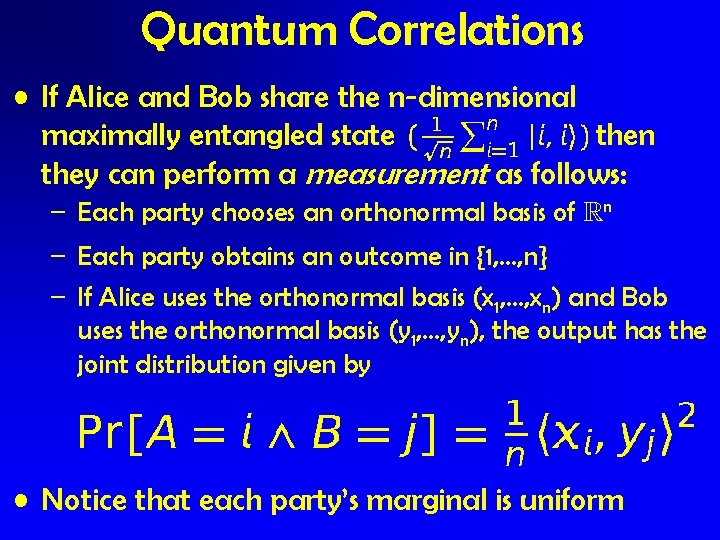

Quantum Correlations • If Alice and Bob share the n-dimensional maximally entangled state then they can perform a measurement as follows: – Each party chooses an orthonormal basis of Rn – Each party obtains an outcome in {1, . . . , n} – If Alice uses the orthonormal basis (x 1, …, xn) and Bob uses the orthonormal basis (y 1, …, yn), the output has the joint distribution given by • Notice that each party’s marginal is uniform

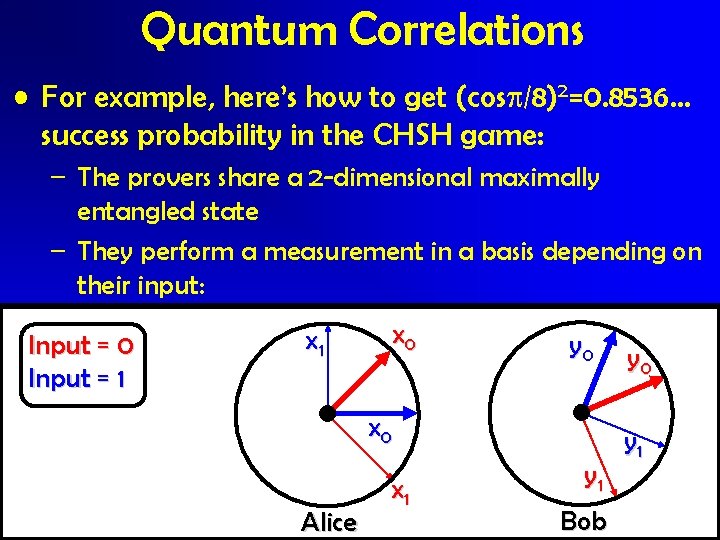

Quantum Correlations • For example, here’s how to get (cos /8)2=0. 8536… success probability in the CHSH game: – The provers share a 2 -dimensional maximally entangled state – They perform a measurement in a basis depending on their input: Input = 0 Input = 1 x 0 x 1 y 0 x 0 Alice x 1 y 1 Bob y 0 y 1

The Proof • For simplicity, let’s consider unique games for which there exists an optimal strategy in which each prover’s answer distribution is uniform over {1, …, k} • Theorem: There exists an efficient algorithm that, given any ‘uniform’ unique game G, outputs a value s. t. 1 -4 *(G) 1 - • Proof: Start by writing an SDP relaxation: • I will not show why this is a relaxation of the entangled value (the proof is not difficult) • Let the value of this SDP be 1 - and output • Our goal is to show that there exists a strategy that achieves success probability 1 -4

The SDP Relaxation • A solution consists of k orthonormal vectors in Rn for each question (for some large n) • In a good solution, the vectors should be ‘aligned’ according to the permutation 1 2 3 4 5…k

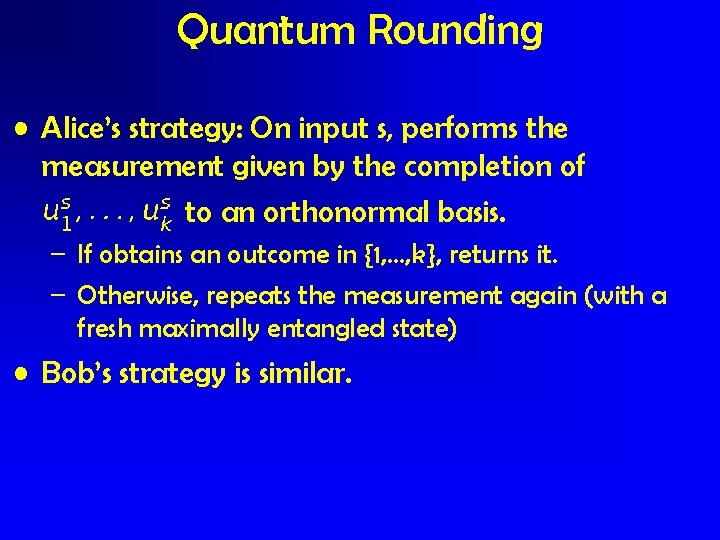

Quantum Rounding – The Idea • Main Idea: On input s, Alice performs the measurement given by. Similarly for Bob using the v vectors. • However, is not a basis of Rn ! • Instead, the provers complete their k vectors to an orthonormal basis of Rn in an arbitrary way

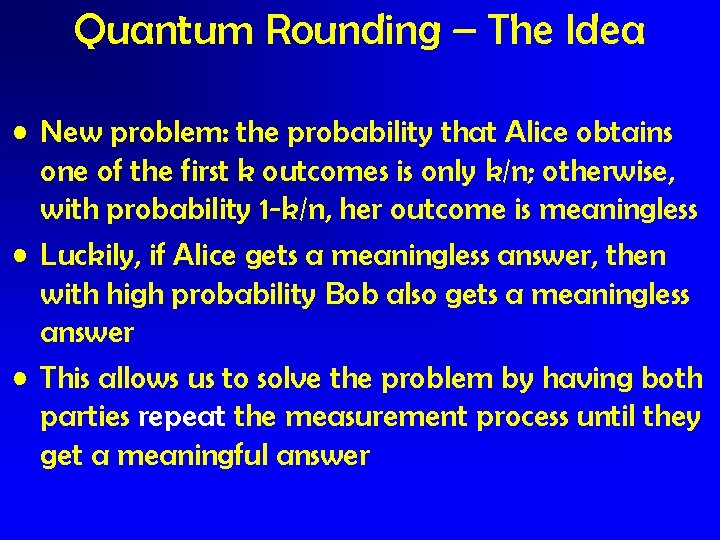

Quantum Rounding – The Idea • New problem: the probability that Alice obtains one of the first k outcomes is only k/n; otherwise, with probability 1 -k/n, her outcome is meaningless • Luckily, if Alice gets a meaningless answer, then with high probability Bob also gets a meaningless answer • This allows us to solve the problem by having both parties repeat the measurement process until they get a meaningful answer

Quantum Rounding • Alice’s strategy: On input s, performs the measurement given by the completion of to an orthonormal basis. – If obtains an outcome in {1, …, k}, returns it. – Otherwise, repeats the measurement again (with a fresh maximally entangled state) • Bob’s strategy is similar.

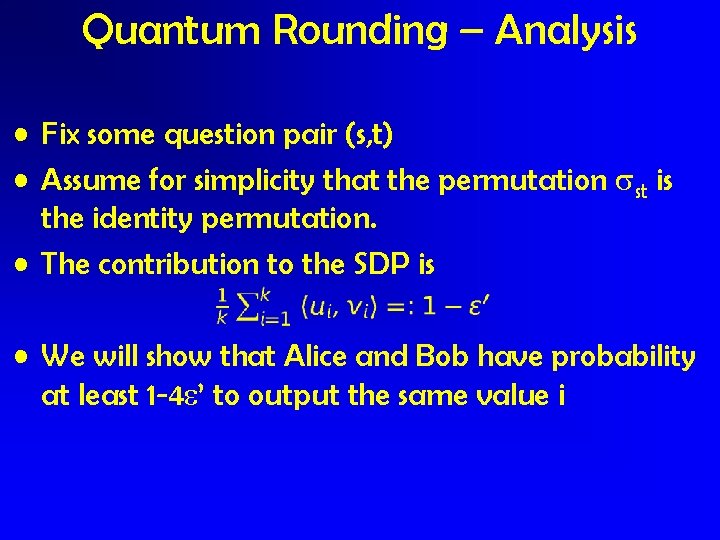

Quantum Rounding – Analysis • Fix some question pair (s, t) • Assume for simplicity that the permutation st is the identity permutation. • The contribution to the SDP is • We will show that Alice and Bob have probability at least 1 -4 ’ to output the same value i

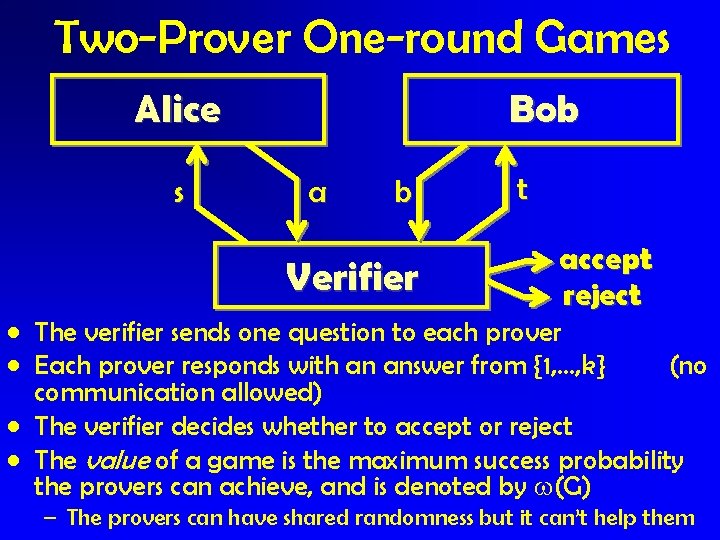

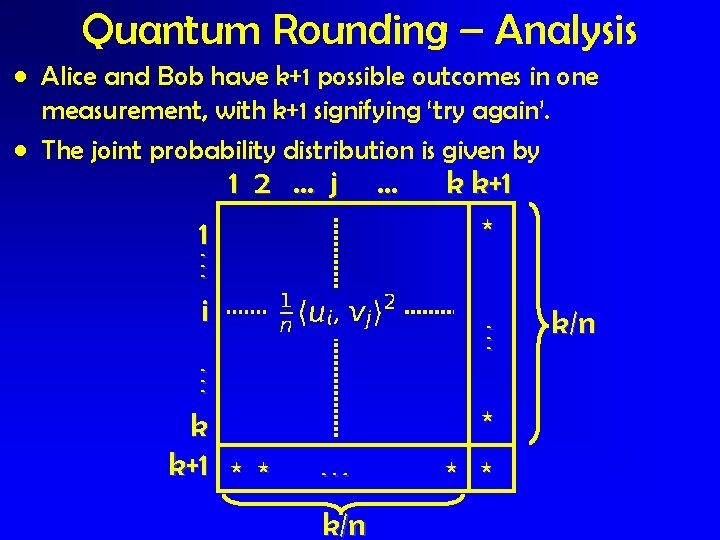

Quantum Rounding – Analysis • Alice and Bob have k+1 possible outcomes in one measurement, with k+1 signifying ‘try again’. • The joint probability distribution is given by 1 2 … j 1 i k k+1 * * … k k+1 * * k/n * * k/n

Quantum Rounding – Analysis • The probability that in one measurement, both Alice and Bob output the same value is • The probability that both of them ‘try again’ is therefore at least • The probability of success is therefore at least

Conclusions • We showed that the entangled value of unique games can be well approximated (up to factor 6) • We extend our results to d-to-d games • Our result also implies a parallel repetition theorem for the entangled value of unique games

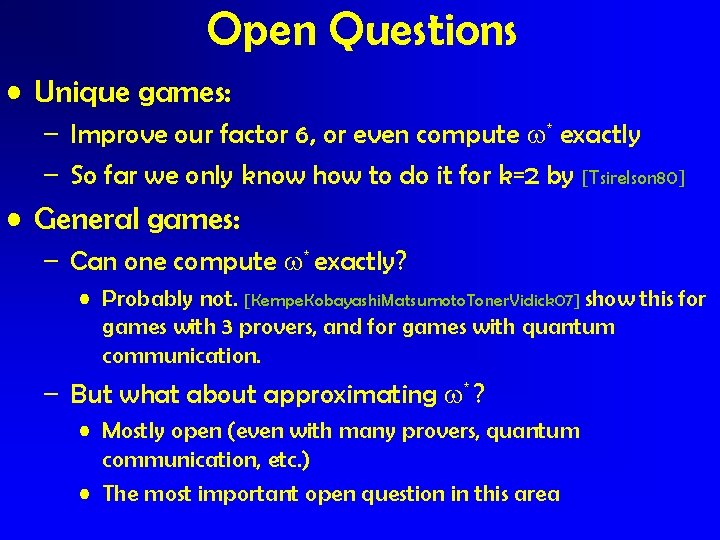

Open Questions • Unique games: – Improve our factor 6, or even compute * exactly – So far we only know how to do it for k=2 by [Tsirelson 80] • General games: – Can one compute * exactly? • Probably not. [Kempe. Kobayashi. Matsumoto. Toner. Vidick 07] show this for games with 3 provers, and for games with quantum communication. – But what about approximating * ? • Mostly open (even with many provers, quantum communication, etc. ) • The most important open question in this area