The Patent System Specification n The specification has

![Principles n [T]he patent should be approached "with a judicial anxiety to support a Principles n [T]he patent should be approached "with a judicial anxiety to support a](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/557103764703f6b293d773edbee93e8f/image-20.jpg)

- Slides: 34

The Patent System

Specification n The specification has two parts: “disclosure” & “claims” 27(3) The specification of an invention must n (a) correctly and fully describe the invention and its operation or use as contemplated by the inventor; (4) The specification must end with a claim or claims defining distinctly and in explicit terms the subject-matter of the invention for which an exclusive privilege or property is claimed.

Specification n The claims define the monopoly n n So that others will know whether they are infringing One of the important features of the claims is to make it clear to other people what they are not entitled to do during the life of the patent. . . n Whitford J, American Cyanamid Co v Berk Pharmaceuticals, Ltd, [1976] RPC 231, 234 (Ch D

Specification n The disclosure describes the invention to the world n So that others will be able to practice the invention after the patent term expires n n ‘Quid pro quo’ for patent monopoly [The disclosure] should be a complete description which will enable anybody, after the patent has expired, to put the invention into practice. n Whitford J, American Cyanamid Co v Berk Pharmaceuticals, Ltd, [1976] RPC 231, 234 (Ch D

Specification n The disclosure also reveals knowledge that may be useful even during the term n n Invention is monopolized, knowledge is not These monopolies are granted to encourage people to make inventions and to make the nature and working of them known. . . n Whitford J, American Cyanamid Co v Berk Pharmaceuticals, Ltd, [1976] RPC 231, 234 (Ch D

Claims n “Embodiment” n n “The inventive concept” n n The specific machine or compound which the inventor has come up with The inventor’s contribution “Invention” n The invention defined by the claims

Claims n The inventor is entitled to claim the inventive concept, not just their particular embodiment n n But the concept must be described in concrete terms But the court will not determine the inventive concept That is left to the inventor in prosecuting the patent n Recall – the inventor (& her agent) writes her own patent n

Claims n The claims define the scope of the monopoly n In an infringement action, the court compares the defendant’s product with the claims not with the plaintiff’s product n Validity, infringement, etc are all determined with reference to the invention as claimed

Claims n “Men substitute words for reality and then fight over words” n Edwin Howard Armstrong, pioneer in radio, on his experiences in patent litigation, quoted by Hayhurst, in Patent Law in Canada

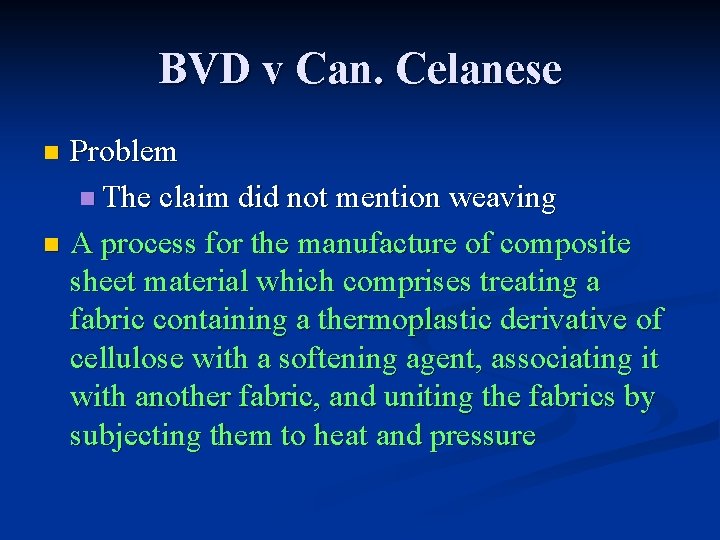

BVD v Can. Celanese Issue: stiffening shirt collars n The prior art consisted of coating material with cellulose which left a stiff and glassy surface: eg the Van Heusen patent n

BVD v Can. Celanese n The substance of the plaintiff’s Dreyfus invention was a method of making a flexible composite textile material by weaving cellulose into the fabric n n the very substance of Dreyfus' invention was. . . to make a composite textile material by taking a plurality of fabrics and uniting them by the use of a fabric composed of or containing yarns, filaments or fibres of a thermoplastic cellulose derivative and the application thereto of heat and pressure There is no doubt that this invention was new, useful and not obvious

BVD v Can. Celanese Problem n The claim did not mention weaving n A process for the manufacture of composite sheet material which comprises treating a fabric containing a thermoplastic derivative of cellulose with a softening agent, associating it with another fabric, and uniting the fabrics by subjecting them to heat and pressure n

BVD v Can. Celanese n The patent was invalid because the scope of the invention as claimed was not novel n The prior art spread the cellulose over the fabric and then applied heat n Spreading falls within “associated”

BVD v Can. Celanese The inventive concept was novel n The invention as claimed was not n n n Result Invalid patent n Note: the consequence is not just that plaintiff loses infringement action, but patent for real invention is rendered worthless by overly broad claims

Claiming n To avoid this problem multiple claims are standard n Begin by claiming the broadest possible scope n Gradually narrow to the specific embodiment

Claiming n Claims stand or fall independently n 58 When, in any action or proceeding respecting a patent that contains two or more claims, one or more of those claims is or are held to be valid but another or others is or are held to be invalid or void, effect shall be given to the patent as if it contained only the valid claim or claims

Construction

Principles n We must look to the whole of the disclosure and the claims to ascertain the nature of the invention and methods of its performance, (Noranda Mines Limited v Minerals Separation North American Corporation [[1950] SCR 36], being neither benevolent nor harsh, but rather seeking a construction which is reasonable and fair to both patentee and public. n Per Dickson J Consolboard Inc v Mac. Millan Bloedel (Saskatchewan Ltd [1981] 1 SCR 504

Principles n There is no occasion for being too astute or technical in the matter of objections to either title or specification for. . . "where the language of the specification, upon a reasonable view of it, can be so read as to afford the inventor protection for that which he has actually in good faith invented, the court, as a rule, will endeavour to give effect to that construction" n Per Dickson J Consolboard Inc v Mac. Millan Bloedel (Saskatchewan Ltd [1981] 1 SCR 504

![Principles n The patent should be approached with a judicial anxiety to support a Principles n [T]he patent should be approached "with a judicial anxiety to support a](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/557103764703f6b293d773edbee93e8f/image-20.jpg)

Principles n [T]he patent should be approached "with a judicial anxiety to support a really useful invention" n Per Dickson J Consolboard Inc v Mac. Millan Bloedel (Saskatchewan Ltd [1981] 1 SCR 504

Specifics The patent is addressed to persons skilled in the art n Expert evidence to explain the meaning of the terms used in a claim is normally required n n n Experts are not permitted to testify as to the meaning of the claim Construction of the patent is for the judge

Specifics The terms of the claims must be interpreted in light of the disclosure n The disclosure cannot be used to change the meaning of the claim n n Eg if more was disclosed than was claimed

True Monopoly v Copyright

American Cyanamid v Berk Pharm n The broad claim would enable the plaintiffs to stop any worker who dug up a soil sample anywhere and found in it a strain of Streptomyces aureofaciens and mutated that strain to produce a near 100 per cent tetracycline-producing strain, from using that strain. . .

American Cyanamid v Berk Pharm n So, on the broad claim, the plaintiffs could seek to stop other workers from reaping the benefit of what might be a long and possibly expensive programme of work and research, to which the plaintiffs, by their disclosure in this patent, could not conceivably have made any kind of contribution.

American Cyanamid v Berk Pharm n It is clear that as between two independent inventors the first to file receives the patent and can exclude the other n Is this case different from a standard case of independent invention? Does Whitford J’s objection apply in the standard case? n What is the response? n

American Cyanamid v Berk Pharm Suppose the only way to independently create the drug is a long and expensive program of research. n Does the result in this case undermine the incentive for the originator to develop the drug in the first place? n

American Cyanamid v Berk Pharm From a public policy perspective, is it good or bad to encourage other researchers to undertake a long and expensive research program in order to develop substantially the same drug? n Why would the originator want a broad patent, if not to prevent independent creation? n

Copyright v Patent Are uncopyrightable “ideas” patentable? n If so, why? n Why are ideas not copyrightable? n How are patents different from copyright in that respect? n n Consider trivial ideas that cost little to develop

Presumption of Validity

Presumption of Validity 43(2) After the patent is issued, it shall, in the absence of any evidence to the contrary, be valid. . . n Is this a substantive burden? n n n That is, should the court defer to the examiner? Or is it only necessary to raise some evidence?

Diversified v Tye-Sil Presumption of validity n Thus the section does impose on the party attacking the patent for invalidity the onus of showing that it is invalid and, in my opinion, the onus so imposed is not an easy one to discharge n n Thorson P n This is not the law

Presumption of Validity n n The law is as follows: . . . the peculiar effect of a presumption 'of law' (that is the real presumption) is merely to invoke a rule of law compelling the jury to reach the conclusion in the absence of evidence to the contrary from the opponent. If the opponent does offer evidence to the contrary (sufficient to satisfy the judge's requirement of some evidence), the presumption disappears as a rule of law, and the case is in the jury's hands free from any rule n Decary JA Diversified Products Corp v Tye-Sil Corp

Presumption of Validity n Is Decary JA right as a matter of policy?