Social Epistemology and argumentation Conceptions of Social Epistemology

- Slides: 19

Social Epistemology and argumentation Conceptions of Social Epistemology

Conceptions of Social Epistemology “We have interests, intrinsic and extrinsic, in acquiring knowledge (true belief) and avoiding error. ” (Goldman 1999: 69) - Epistemology evaluates practices along truth-linked (veritistic) dimensions. Social epistemology evaluates specifically social practices along these dimensions. Competitors to veritism 1. Consensus consequentialism Pure consequentialism: social practices ought to be evaluated by their ability to promote agreement. - In the writings of Jürgen Habermas (1984), John Rawls (1993), Bruce Ackerman (1989), and, in argumentation theory Frans van Eemeren and Rob Grootendorst (1984, 2004)

Conceptions of Social Epistemology A) When we argue, we typically try to get the interlocuter to agree – mediators are sometimes employed to help reach agreement. B) Philosophers of science of cite intersubjectivity as a distinguishing mark of science. - The context of these writers (excluding van Eemeren and Grootendorst) is political and social philosophy; discussion in order to reach a decision on what to do (practical reasoning as opposed to theoretical reasoning). So, what is reasonable for them to take into focus is not necessarily reasonable for social epistemology. Cases against: totalitarian news coverage. Biased jury selection. Belief pill for scientists. - If the goal is set for achieving rational agreement, the evaluation is different. - Why do we want others to agree with us? Is agreement a tell-tale sign of truth?

Conceptions of Social Epistemology 2. Pragmatism Social belief-causing mechanisms should be evaluated by the amount of utility that they would produce. - One motivation: truth is a notion to be avoided. “Success” as goal achievement or desire-fulfillment involves something more concrete. However, in comparison to correspondence theory (for example), it seems to involve a reference to relation between mind and world, only the direction of fit is different. Stich (1990: ch. 5): We have no reason to prefer truth We have belief tokens (mental states) that are mapped onto the world by an interpretation function. But the interpretation function could have been set differently, hence, they all could have received a different mapping. How the mapping is now is merely a historical coincident, and we have no principled way of deciding between them.

Conceptions of Social Epistemology There is no water in the sun-> true if and only there is no H 20 in the sun (Function: reference) There is no water in the sun-> true if and only if there is no H 20 or XYZ in the sun (Function: reference*) … Objections: Goldman (1999, 72 -73): if this is a real problem, then a similar problem would beset satisfaction. Namely, there could be satisfaction, satisfaction**, … Alston (1996): Stich confuses truth conditions, i. e. the assigning of propositional content to bearers of such contents (beliefs), with truth value, i. e. the relation a given proposition to the world.

Conceptions of Social Epistemology Stich: we have no general argument for the claim that believing a true claim is always more beneficial than believing a false claim. Goldman: “If I adopt means M, then I will achieve end E. ” - Assume that agent A values E more than anything else, A is in a position to adopt M, and there is no other means M* that A believes would establish E. Suppose further that the means-end proposition is true and M is adopted. E follows. So there is at least some connection, and many inferential procedures feed this kind of reasoning. True beliefs about the consequences of our actions are the most useful ones in establishing what to do and, thus, satisfy our interests. - Second, we do value truth in itself in, for example, science and law.

Conceptions of Social Epistemology 3. Proceduralism All the previous account are consequentialist: they identify some fundamental aim (true belief / consensus / utility satisfaction) and evaluate social practices in relation to achieving this aim. Are there any alternatives that locate the value in the procedure itself? Certain models of deliberative democracy (Mill, Arendt, Habermas) hold that a certain kind of democratic procedure (deliberation) is valuable in itself. - But this is disputed by many theorists of deliberative democracy (Elster, Estlund). Anyway, as Goldman (1999: 77) notes, such a procedure would not be relevant to all social activities pertaining to knowledge. For example, the norms of ideal speech situation do not apply to mass communication or to science.

Conceptions of Social Epistemology Objectivity: Helen Longino (1990: 76) has argued that objectivity is the ultimate aim, and a scientific communities exhibit objectivity to the degree that they satisfy four criteria necessary for achieving the transformative dimension of critical discourse: 1) There must recognized avenues for the criticism of evidence, of methods, and of assumptions of reasoning; 2) there must exist a shared standards that critics can invoke; 3) the community as a whole must be responsive to such criticisms; 4) intellectual authority must be shared equally among qualified practitioners. - However, it seems that Longino advocates objectivity and impartiality in place of subjectivity and partiality in order to avoid arbitrariness. But nonarbitrariness has instrumental value: it promotes finding the truth. So the criteria seems consequentalist.

Conceptions of Social Epistemology Rationality: there accounts of rationality as a non-consequentalist approach. - Goldman argues that theorists of rationality are a) unable to give a nonconsequentalist accounts. For example, a Bayesian account of rationality ultimately refers to disutility, i. e. losing money; and b) too limited in scope. For example, there is no single way of describing reporting in terms of rationality. A different challenge issues from Siegel (2005) “…education should strive to foster, not (just) true belief, but (also) the skills, abilities and dispositions constitutive of critical thinking, and the rational belief generated and sustained by it. ” - Discusses education but I believe that the issue has wider application, though does not necessarily extend to all areas of social epistemology. - Accepts that both aims are important. - Goldman accepts that critical thinking has value, but emphasizes that the value is instrumental.

Conceptions of Social Epistemology 1. One or many aims? From the fact that truth is taken as a central aim, it does not follow that it must be the sole aim: - Truth is naturally a central aim: what is taught is considered to be true. - The point of teaching justified beliefs, however, is the idea that justification is a fallible indicator of truth. 1. 2. 3. If mere true belief is the sole aim, then brainwashing, indoctrination, chemical manipulation etc. would be acceptable methods. They are not acceptable methods. Therefore, true belief is not the sole aim. The point is that students ought to believe the true, because of the reasons the teachers think are good reasons for believing the true. Good reasons are intertwined with education. The object ought to be knowledge in the strong sense: justified true belief.

Conceptions of Social Epistemology 2. Bare difference argument Assume that two agents, Maria and Mario, have identical beliefs, the only difference being that one has a rationally held belief and the other does not. First assume that the belief is true. Is there is a difference? Then assume that the belief is false. Is there a difference. In both cases, if Maria’s belief is held rationally and Mario’s belief is a lucky guess, Maria’s belief seems more commendable.

Conceptions of Social Epistemology 3. Access to truth For most beliefs, it seems that we have no direct access to their truth: we have to reason evidentially, i. e. judge whether p is true based on evidence and reasoning. But this is not easy; students therefore need to develop skills and dispositions that allow them to reason well, evaluate evidence well, search for evidence, construct and evaluate arguments well, etc. R. Firth: “To the extent that we are rational, each of us decides at any time t whether a belief is true, in precisely the same way that we would decide at t whether we ourselves are, or would be, warranted at t in having that belief. ” (1981: 19). As Siegel notes, even Goldman makes this point: “The usual route to true belief, of course, is to obtain some kind of evidence that points to the true proposition and away from the rivals” (1999: 24)

Conceptions of Social Epistemology Argument here: 1. Truth can be determined only by certain methods. 2. As educators, we want students to be able to determine (i. e. be able and disposed to seek) the truth. 3. Therefore, in education the ultimate end is not truth per se, but enabling students to judge or estimate wisely. Enlarged argument: 1. Truth can be determined only by certain methods m 1, …, mn. 2. As educators, we want students to be able to determine (i. e. be able and disposed to seek) the truth. 3. Therefore, we need to teach the students methods m 1, …, mn. 4. Methods in themselves are not sufficient for a critical thinker but also relevant dispositions (Siegel 1988). 5. Therefore, in education the ultimate end is not truth per se, but enabling the students to judge or estimate wisely (by giving certain skills and dispositions).

Conceptions of Social Epistemology 4. Fundamental aims outside education Goldman (2001: 34) has argued that a main problem for deontological evidentialism ((DE): the view that an agent should assign a degree a belief to a proposition in proportion to the weight of evidence she possesses) is that it cannot account for the virtue of evidence gathering: 1. DE is not consequentialist (proportioning is not justified by its ability to lead to truth or some other value). 2. If one only needs to proportion belief to evidence, the easiest way to do this is to not believe anything. 3. But this leads to investigational sloth, which is unacceptable. 4. Therefore, DE cannot be the underlying value behind all epistemic virtues.

Conceptions of Social Epistemology Replies noted by Siegel: - The relevant epistemological duty is rational belief – if I have done all I can to believe rationally, I have done my epistemological duty (Feldman 2002). - DE can somehow account for the virtues. - ‘Investigational sloth’ can be criticized as a failure of character. But most importantly: - This criticism does nothing against the virtue monism that Siegel represents, which accepts that rational belief also has instrumental virtue. Accounting for virtues: - We are often required by our role as a citizen, a parent, a professional, a member of a given board, etc. to know about the relevant issues. - Similar considerations seem relevant if one were to enlarge the fundamental aim of rational belief outside education: to politics, law, … - The role of trust seems essential: to what extent can we, and should we trust individuals and institutions, if they are not able to justify their positions with reasons we can accept?

Conceptions of Social Epistemology Possible counters for Goldman’s position: 1. Rational belief, i. e. belief reached by critical thinking, is only meaningful in terms of instrumental value. Siegel admits that Goldman has an argumentative advantage here but argues that his arguments show there is more to rational belief than But: De. Paul (2001) has noted both of the following cannot be true: a) knowledge is epistemically better than mere true belief; and b) true belief is the only epistemic good. The new evil demon –problem (Cohen and Lehrer): suppose you have a twin that has through her/his whole life been deceived by the evil demon. S/he has had all the experiences you have had but all of them have been false. We seem to have the intuition that your twin is justified in her/his beliefs. But then, “proper contact” with the world is not essential for justification. 2. Siegel’s position involves a confusion between a test for whether the fundamental aim has been achieved and the aim itself.

Conceptions of Social Epistemology 5. Reasons for Critical Thinking outside epistemology 1. We want to students (and persons in general) to be reflective: to take our fallibility seriously. 2. Education is not only a propositional matter: it needs to develop dispositions and particular traits of character. - To counter (in favor of Goldman): if one takes as fundamental aim true beliefs, the next question is “Which true beliefs? ” It seems essential to teach methods and dispositions that will produce the largest amount of true beliefs about relevant matters over a long period of time (and after education). Critical thinking can be justified from this consequentialist and veritistic position. 3. Education ought to foster autonomy. Siegel quotes Israel Scheffler (1989: 139) that we must “surrender the idea of shaping or molding the mind of the pupil. The function of education… is rather to liberate the mind, strengthen its critical powers, [and] inform it with knowledge and the capacity to independent inquiry. ” So, Siegel concludes: critical thinking can be justified from both within epistemology and from perspectives outside, without denying the important instrumentalist link.

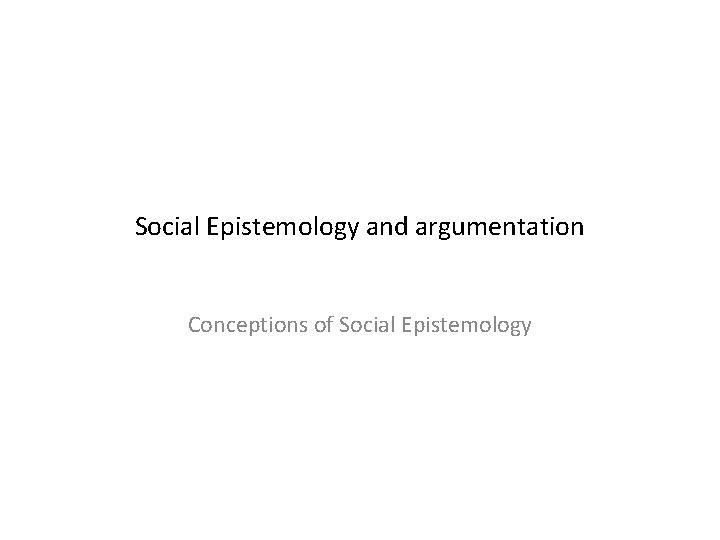

Conceptions of Social Epistemology How is veritism empolyed and how does it look like in practice? Truth is set as the ultimate aim; procedures are evaluated in respect to their ability to produce V-value. For example, the values for belief, withholding, and rejection: V-value of B(true) = 1 V-value of W(true) =. 5 V-value of R(true) = 0 For degree of belief: V-value DBx = X A good procedure gives us high (or higher than others) V-value in respect to questions of interest. This does not imply that we can, in practice, appraise V-values (at least any better than those involved in the process), but it does give us a theoretical way to present what we are after. Further complications arise out of the concept of interest, complex agents (who needs to know what) and causal attribution (what does eventually affect our beliefs).

References Ackerman, B. 1989. Why Dialogue? Journal of Philosophy 86: 5 -22. Alston, W. 1996. A Realist Conception of Truth. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. De. Paul, M. R. 2001. Value Monism in Epistemology. In M. Steup (ed. ) Knowledge, Truth and Duty: Essays on Epistemic Justification, Responsibility, and Virtue. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Eemeren, F. and R. Grootendorst. 1984. Speech Acts in Argumentative Discussion. Dordrecht, Holland: Foris Publications. Eemeren, F. and R. Grootendorst. 2004. A Systematic Theory of Argumentation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Feldman, R. 2002. Epistemological Duties. In P. Moser (ed. ) The Oxford Handbook of Epistemology. Firth, R. 1981. Epistemic Merit, Intrinsic and Instrumental. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Association, vol. 55: 5 -23. Goldman, A. 1999. Knowledge in a Social World. Oxford: Princeton Press. Goldman, A. 2001. The Unity of Epistemic Virtues. In A. Fairweather and L. Zagrebski (eds. ) Virtue Epistemology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Habermas, J. 1984. Theory of Communicative Action, 2 vols. Transl. T. Mc. Carthy. Boston, Mass. : Beacon. Longino, H. 1990. Science as Social Knowledge. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Rawls, J. 1993. Political Liberalism. New York: Columbia University Press Scheffler, I. 1989. Reason and Teaching. Indianpolis: Hackett. Siegel, H. 1988. Educating Reason: Rationality, Critical Thinking, and Education. London: Routledge. Siegel, H. 2005. Trust, Thinking, Testimony and Trust: Alvin Goldman on Epistemology and Education. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. Vol. LXXI: 345 -366.

Spiritual conceptions

Spiritual conceptions English syntax and argumentation

English syntax and argumentation 4 types of editorial writing

4 types of editorial writing Retorik og argumentation

Retorik og argumentation Types of inductive reasoning

Types of inductive reasoning Induktive und deduktive argumentation

Induktive und deduktive argumentation Forvægt og bagvægt

Forvægt og bagvægt Tierversuche argumentation

Tierversuche argumentation Sanduhr methode erörterung

Sanduhr methode erörterung Argumentation einleitung

Argumentation einleitung Juridisk argumentation

Juridisk argumentation Introduction to argumentation

Introduction to argumentation Psychologisches gutachten aufbau

Psychologisches gutachten aufbau For and against essay linking words

For and against essay linking words Argumentation

Argumentation Free will defense theodizee

Free will defense theodizee Logos argumentation

Logos argumentation Linking words for arguments

Linking words for arguments These beispiel argument

These beispiel argument Epistemology vs ontology

Epistemology vs ontology