Renaissance Poetry preliminaries what informs Renaissance poetry education

- Slides: 21

Renaissance Poetry

preliminaries: what informs Renaissance poetry education – grammar schools and universities > more widely available (cf. grammar school in Stratford) > curriculum restructured reflecting the concerns of humanism: emphasis on a combination of 1) rhetorical training (in Latin); 2) reading the classics + learning procedures based on simultaneous reading/rewriting: translation, paraphrase, metaphrase, summary, declamation, imitation (methods outlined in Roger Ascham’s The Scholemaster, 1570); note-taking in “commonplace books” – model treatments of a theme, problem etc. perspective of poetry – emphasis on exemplary function (moral, practical) “Poesy, therefore, is an art of imitation […] a representing, counterfeiting, or figuring forth […] with this end, to teach and delight. […] If the poet do his part aright, he will show you in Tantalus, Atreus, and such like, nothing that is not to be shunned; in Cyrus, Aeneas, Ulysses, each thing to be followed” – Sir Philip Sidney, The Defence of Poesy Compare A Mirror for Magistrates (1559) – a collection of poems in which the ghosts of eminent statesmen recount their downfalls in first-person narratives called ‘tragedies’ or ‘complaints’ as an example for those currently in power

mapping Renaissance poetry basic coordinates: the poet gentlemen scholars vs. aspiring writers Sir Thomas Wyatt; Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey; Sir Philip Sidney Edmund Spenser; George Chapman; Ben Jonson the genre “intimate” vs. “public”; (certain types) of lyric X epic poetry We can die by it, if not live by love, And if unfit for tomb or hearse Our legend be, it will be fit for verse ; And if no piece of chronicle we prove, We'll build in sonnets pretty rooms ; As well a well-wrought urn becomes The greatest ashes, as half-acre tombs, And by these hymns, all shall approve Us canonized for love […] John Donne: The Canonization the medium manuscript vs. print

the lyric: a courtly pastime goes public poetry and poets at the court of Henry VIII writing poetry was a recognized “courtly” accomplishment and activity: Henry VIII’s Manuscript – contains poems by the king; cf. Pastime With Good Company a social act reflecting and shaping one’s place in the courtly milieu Sir Thomas Wyatt (1503 – 1542) “Like Sidney, fifty years later, Wyatt has some claim to be seen as an all-round Renaissance man […] a soldier, statesman, diplomat, linguist and courtier. ” – Gary F. Waller, English Poetry of the Sixteenth Century Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey (1516/1517 – 1547) both had a very turbulent court career (diplomatic missions, army command, repeated imprisonment…) experimented with Italian lyric forms – introduced and developed the sonnet, first in translations from Petrarch, subsequently in their own compositions – used a range of other lyrical forms (Wyatt: terza rima, ottava rima, rondeau…) but also cultivated existing English models (Wyatt: They Flee From Me – rhyme royal, introduced and popularized by Chaucer) → continuity and innovation (cf. the Devonshire MS: a courtly production, incl. lyrics by, among others, Wyatt, but also Chaucer)

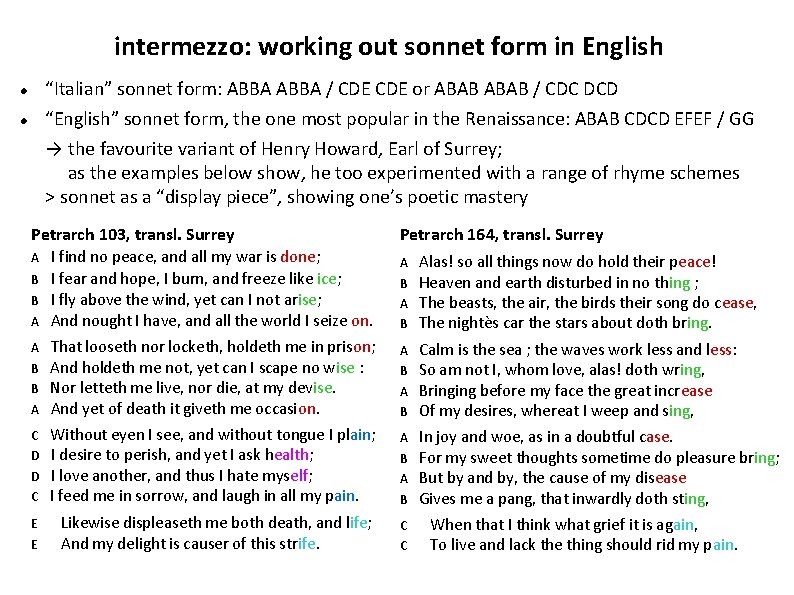

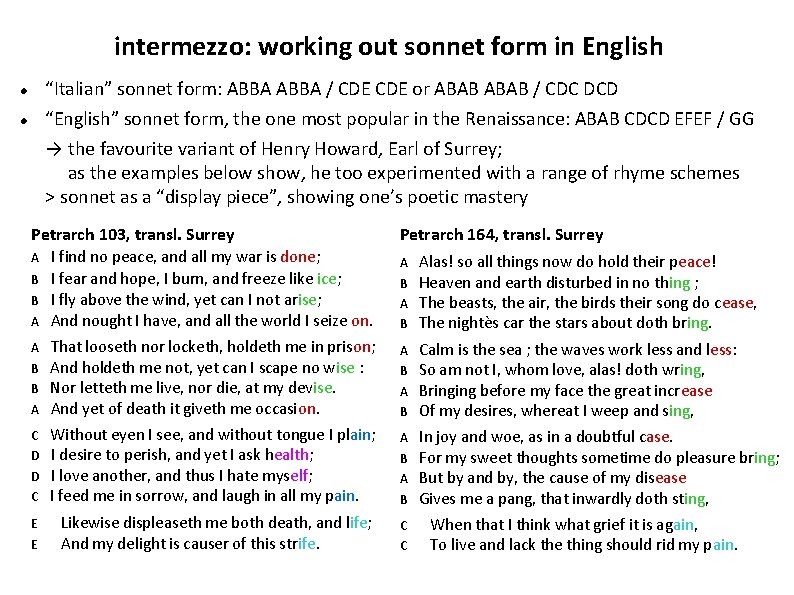

intermezzo: working out sonnet form in English “Italian” sonnet form: ABBA / CDE or ABAB / CDC DCD “English” sonnet form, the one most popular in the Renaissance: ABAB CDCD EFEF / GG → the favourite variant of Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey; as the examples below show, he too experimented with a range of rhyme schemes > sonnet as a “display piece”, showing one’s poetic mastery Petrarch 103, transl. Surrey Petrarch 164, transl. Surrey I find no peace, and all my war is done; B I fear and hope, I burn, and freeze like ice; B I fly above the wind, yet can I not arise; A And nought I have, and all the world I seize on. A B Alas! so all things now do hold their peace! Heaven and earth disturbed in no thing ; The beasts, the air, the birds their song do cease, The nightès car the stars about doth bring. A B B A That looseth nor locketh, holdeth me in prison; And holdeth me not, yet can I scape no wise : Nor letteth me live, nor die, at my devise. And yet of death it giveth me occasion. A B Calm is the sea ; the waves work less and less: So am not I, whom love, alas! doth wring, Bringing before my face the great increase Of my desires, whereat I weep and sing, C D D C Without eyen I see, and without tongue I plain; I desire to perish, and yet I ask health; I love another, and thus I hate myself; I feed me in sorrow, and laugh in all my pain. A B In joy and woe, as in a doubtful case. For my sweet thoughts sometime do pleasure bring; But by and by, the cause of my disease Gives me a pang, that inwardly doth sting, E Likewise displeaseth me both death, and life; And my delight is causer of this strife. C C A E When that I think what grief it is again, To live and lack the thing should rid my pain.

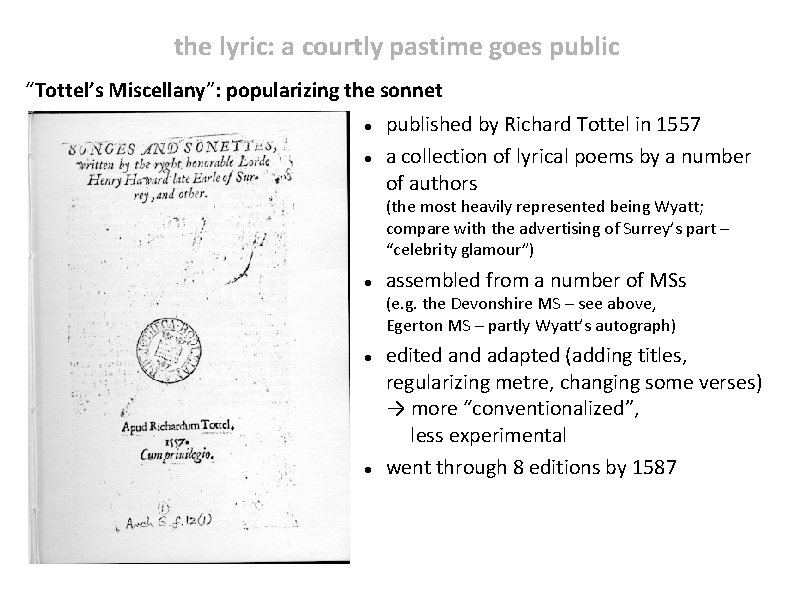

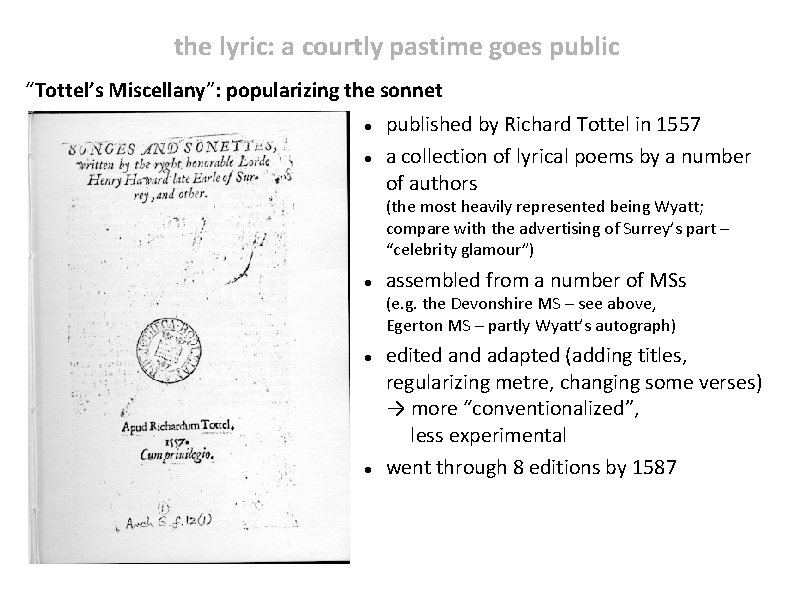

the lyric: a courtly pastime goes public “Tottel’s Miscellany”: popularizing the sonnet published by Richard Tottel in 1557 a collection of lyrical poems by a number of authors (the most heavily represented being Wyatt; compare with the advertising of Surrey’s part – “celebrity glamour”) assembled from a number of MSs (e. g. the Devonshire MS – see above, Egerton MS – partly Wyatt’s autograph) edited and adapted (adding titles, regularizing metre, changing some verses) → more “conventionalized”, less experimental went through 8 editions by 1587

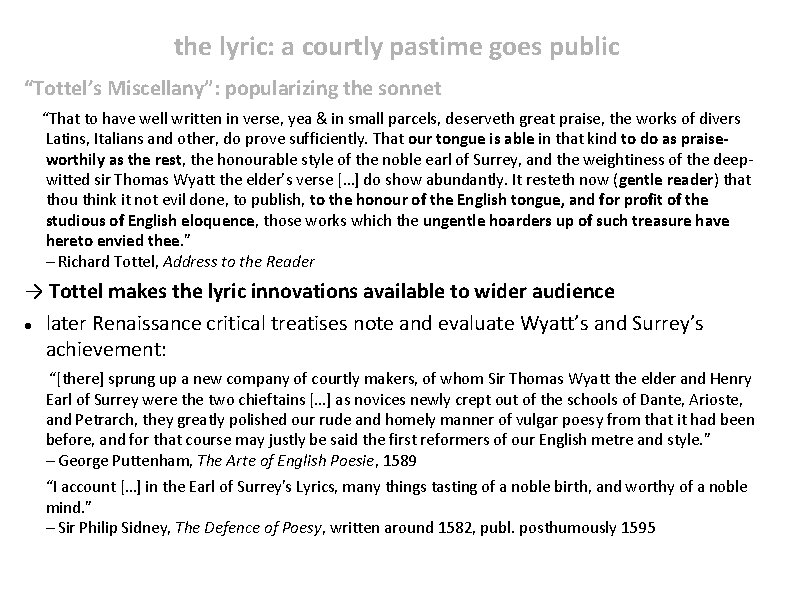

the lyric: a courtly pastime goes public “Tottel’s Miscellany”: popularizing the sonnet “That to have well written in verse, yea & in small parcels, deserveth great praise, the works of divers Latins, Italians and other, do prove sufficiently. That our tongue is able in that kind to do as praiseworthily as the rest, the honourable style of the noble earl of Surrey, and the weightiness of the deepwitted sir Thomas Wyatt the elder’s verse […] do show abundantly. It resteth now (gentle reader) that thou think it not evil done, to publish, to the honour of the English tongue, and for profit of the studious of English eloquence, those works which the ungentle hoarders up of such treasure have hereto envied thee. ” – Richard Tottel, Address to the Reader → Tottel makes the lyric innovations available to wider audience later Renaissance critical treatises note and evaluate Wyatt’s and Surrey’s achievement: “[there] sprung up a new company of courtly makers, of whom Sir Thomas Wyatt the elder and Henry Earl of Surrey were the two chieftains […] as novices newly crept out of the schools of Dante, Arioste, and Petrarch, they greatly polished our rude and homely manner of vulgar poesy from that it had been before, and for that course may justly be said the first reformers of our English metre and style. ” – George Puttenham, The Arte of English Poesie, 1589 “I account […] in the Earl of Surrey's Lyrics, many things tasting of a noble birth, and worthy of a noble mind. ” – Sir Philip Sidney, The Defence of Poesy, written around 1582, publ. posthumously 1595

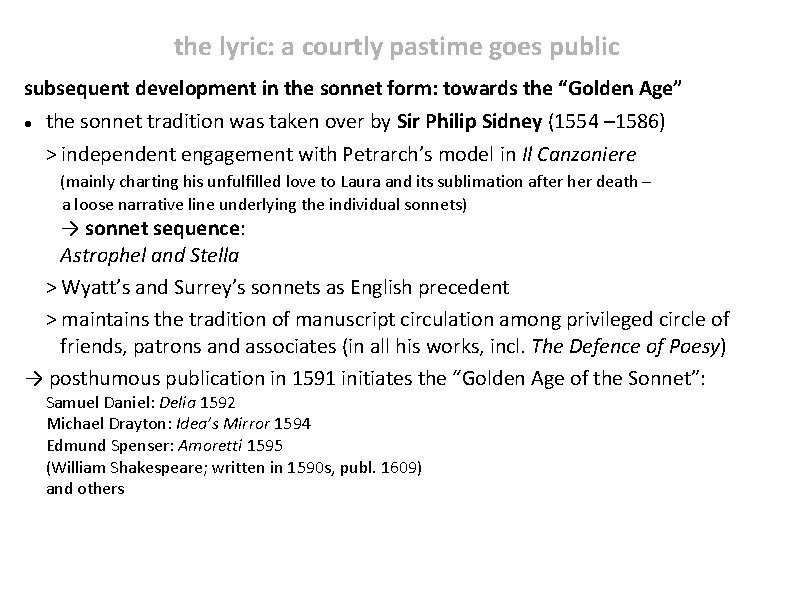

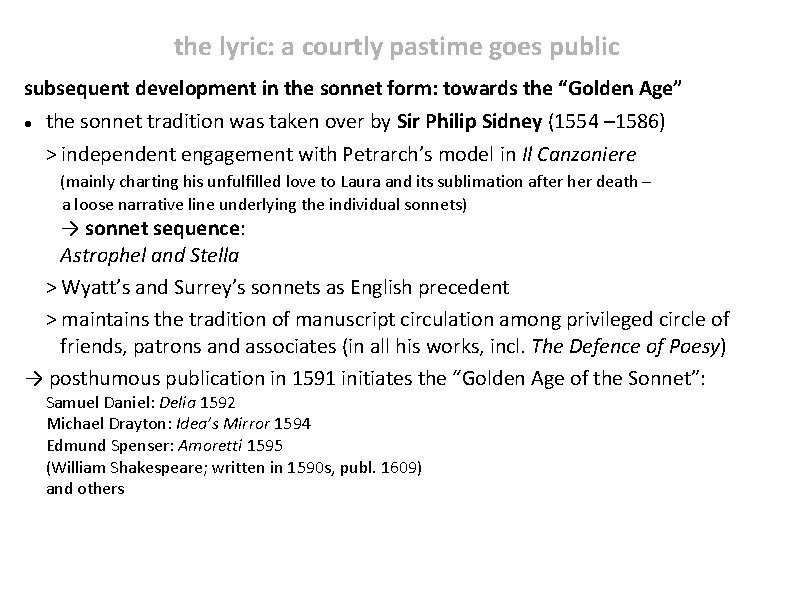

the lyric: a courtly pastime goes public subsequent development in the sonnet form: towards the “Golden Age” the sonnet tradition was taken over by Sir Philip Sidney (1554 – 1586) > independent engagement with Petrarch’s model in Il Canzoniere (mainly charting his unfulfilled love to Laura and its sublimation after her death – a loose narrative line underlying the individual sonnets) → sonnet sequence: Astrophel and Stella > Wyatt’s and Surrey’s sonnets as English precedent > maintains the tradition of manuscript circulation among privileged circle of friends, patrons and associates (in all his works, incl. The Defence of Poesy) → posthumous publication in 1591 initiates the “Golden Age of the Sonnet”: Samuel Daniel: Delia 1592 Michael Drayton: Idea’s Mirror 1594 Edmund Spenser: Amoretti 1595 (William Shakespeare; written in 1590 s, publ. 1609) and others

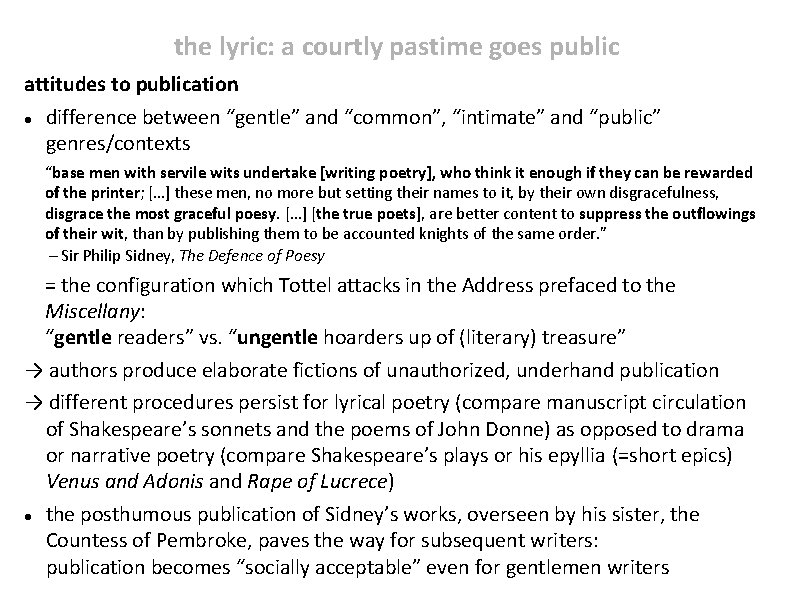

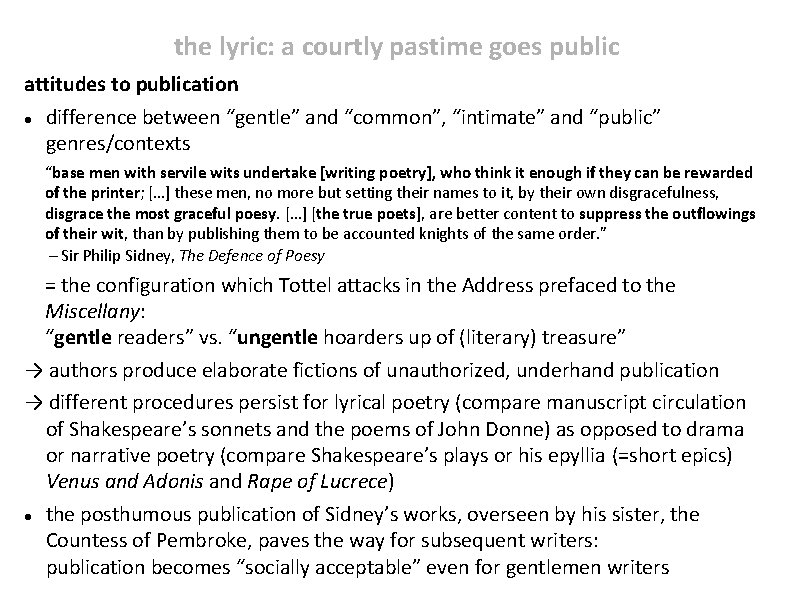

the lyric: a courtly pastime goes public attitudes to publication difference between “gentle” and “common”, “intimate” and “public” genres/contexts “base men with servile wits undertake [writing poetry], who think it enough if they can be rewarded of the printer; […] these men, no more but setting their names to it, by their own disgracefulness, disgrace the most graceful poesy. […] [the true poets], are better content to suppress the outflowings of their wit, than by publishing them to be accounted knights of the same order. ” – Sir Philip Sidney, The Defence of Poesy = the configuration which Tottel attacks in the Address prefaced to the Miscellany: “gentle readers” vs. “ungentle hoarders up of (literary) treasure” → authors produce elaborate fictions of unauthorized, underhand publication → different procedures persist for lyrical poetry (compare manuscript circulation of Shakespeare’s sonnets and the poems of John Donne) as opposed to drama or narrative poetry (compare Shakespeare’s plays or his epyllia (=short epics) Venus and Adonis and Rape of Lucrece) the posthumous publication of Sidney’s works, overseen by his sister, the Countess of Pembroke, paves the way for subsequent writers: publication becomes “socially acceptable” even for gentlemen writers

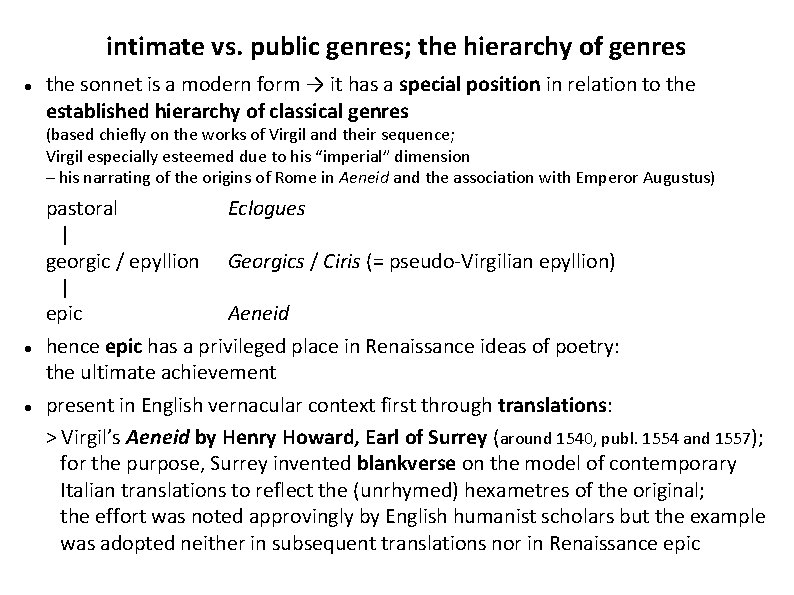

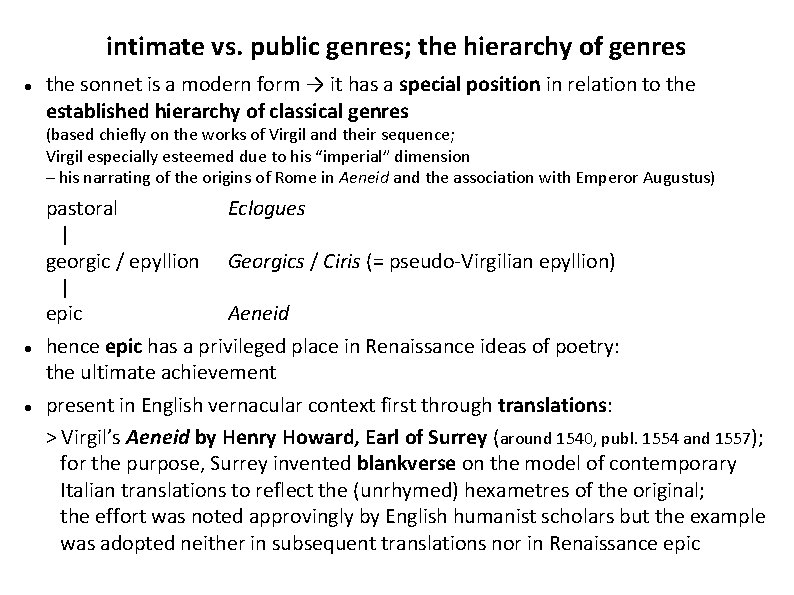

intimate vs. public genres; the hierarchy of genres the sonnet is a modern form → it has a special position in relation to the established hierarchy of classical genres (based chiefly on the works of Virgil and their sequence; Virgil especially esteemed due to his “imperial” dimension – his narrating of the origins of Rome in Aeneid and the association with Emperor Augustus) pastoral Eclogues | georgic / epyllion Georgics / Ciris (= pseudo-Virgilian epyllion) | epic Aeneid hence epic has a privileged place in Renaissance ideas of poetry: the ultimate achievement present in English vernacular context first through translations: > Virgil’s Aeneid by Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey (around 1540, publ. 1554 and 1557); for the purpose, Surrey invented blankverse on the model of contemporary Italian translations to reflect the (unrhymed) hexametres of the original; the effort was noted approvingly by English humanist scholars but the example was adopted neither in subsequent translations nor in Renaissance epic

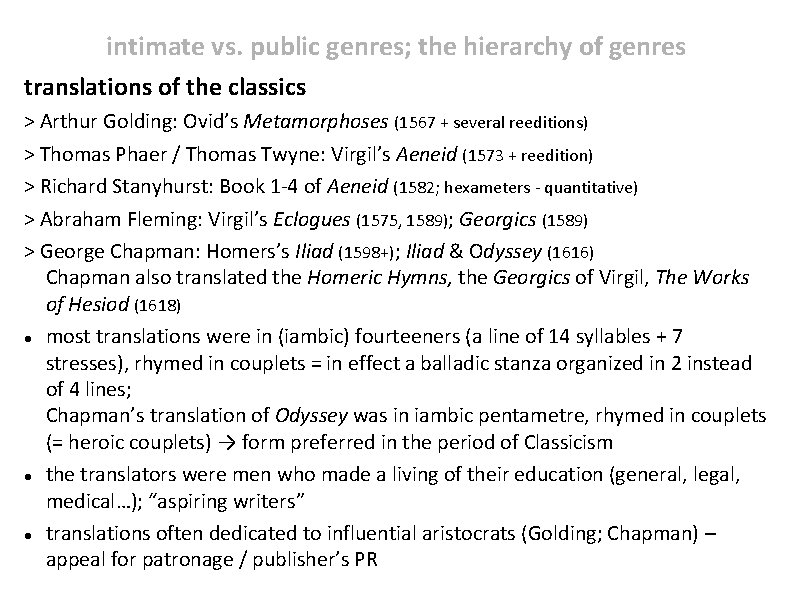

intimate vs. public genres; the hierarchy of genres translations of the classics > Arthur Golding: Ovid’s Metamorphoses (1567 + several reeditions) > Thomas Phaer / Thomas Twyne: Virgil’s Aeneid (1573 + reedition) > Richard Stanyhurst: Book 1 -4 of Aeneid (1582; hexameters - quantitative) > Abraham Fleming: Virgil’s Eclogues (1575, 1589); Georgics (1589) > George Chapman: Homers’s Iliad (1598+); Iliad & Odyssey (1616) Chapman also translated the Homeric Hymns, the Georgics of Virgil, The Works of Hesiod (1618) most translations were in (iambic) fourteeners (a line of 14 syllables + 7 stresses), rhymed in couplets = in effect a balladic stanza organized in 2 instead of 4 lines; Chapman’s translation of Odyssey was in iambic pentametre, rhymed in couplets (= heroic couplets) → form preferred in the period of Classicism the translators were men who made a living of their education (general, legal, medical…); “aspiring writers” translations often dedicated to influential aristocrats (Golding; Chapman) – appeal for patronage / publisher’s PR

Renaissance English literature & its concerns: Edmund Spenser (1552/1553 – 1599) his career and output illustrate the aspirations and contexts of Renaissance literary production “aspiring writer” – does not make his living by writing but writing is an integral part of his self-fashioning as “man of letters” – the basis for his career • coming from artisan family • obtained education at Merchant Taylors’School = one of the new grammar schools, headed by an education theorist Richard Mulcaster; curriculum characterized by training in classics but respect for the vernacular: “I love Rome, but London better […] I honour the Latin, but I worship the English” – Mulcaster • studied at Cambridge • there established friendships and connections which shaped his subsequent career: > Dr John Young, a master of the college > through an elder colleague, Gabriel Harvey, got to know Sir Philip Sidney & his powerful uncle Leicester (advisor to the Queen) → potential for preferment, access to the Court; his pastoral dedicated to Sidney • through those links obtained positions as secretary to 1) Young, then Bishop of Rochester 2) Arthur Lord Grey de Wilton, appointed as the Lord Deputy of Ireland (nomination supported by Leicester) later also more official administrative positions in Ireland: Justice for County Cork, Sheriff of Cork • finally established in Ireland as a member of gentry with the grant of 3028 acres in the Munster Plantation (land confiscated after suppressed insurrection), position confirmed by his marriage • forges association with Sir Walter Raleigh → obtains audience with the Queen, presents his epic; • returns to Ireland (disaffected? ); writes a series of minor works

Renaissance English literature & its concerns: Edmund Spenser’s career shows • the importance of patronage and membership in a (literary) circle around an important “gentleman scholar” (Sidney, Raleigh…) • his aspirations (ultimately disappointed) to “court poet” status • his paradoxical position: poet producing “core” genres with imperial associations writing from the periphery Spenser’s output: his major “public” works are presented as clearly programmatic in • the choice of genres and experiments with style (language) and form (verse): The Shepheardes Calender (1579) → The Faerie Queene (1590; 1596) = from pastoral to epic • the prefatory material explaining his models and goals • presentation in print

Renaissance English literature & its concerns: Edmund Spenser The Shepheardes Calender

Renaissance English literature & its concerns: Edmund Spenser The Shepheardes Calender (1579) • published anonymously • 12 eclogues; each in different verse form • working out a proper “pastoral” style: “rustic” (hints of country dialect); archaic diction “For in my opinion it is one special praise, of many which are due to this Poet, that he hath laboured to restore, as to their rightful heritage such good and natural English words, as have ben long time out of use and almost clean disinherited. Which is the only cause, that our Mother tongue, which truly of it self is both full enough for prose and stately enough for verse, hath long time been counted most bare and barren of both. ” – introductory “Commendation” from The Shepheardes Calender “The ‘Shepherds' Kalendar’ hath much poesy in his eclogues, indeed, worthy the reading, if I be not deceived. That same framing of his style to an old rustic language, I dare not allow; since neither Theocritus in Greek, Virgil in Latin, nor Sannazaro in Italian, did affect it. ” – Sidney, The Defence of Poesy • allegorical – scenes of pastoral life comment on moral, political, religious issues on the model of Virgil who alludes to contemporary politics in his Eclogues “[…] following the example of the best & most ancient Poets, which devised this kind of writing […] at the first to try their abilities? and as young birds, that be newly crept out of the nest, by little first to prove their tender wings, before they make a greater flight. So flew Theocritus, as you may perceive he was allready full fledged. So flew Virgil, as not yet well feeling his wings. So flew Mantuan, as being not full sound. So Petrarch. So Boccaccio; So Marot, Sannazaro, and also divers other excellent both Italian and French Poets, whose footing this Author everywhere followeth […]. So finally flieth this our new Poet, as a bird, whose principals be scarce grown out, but yet as that in time shall be able to keep wing with the best. ”

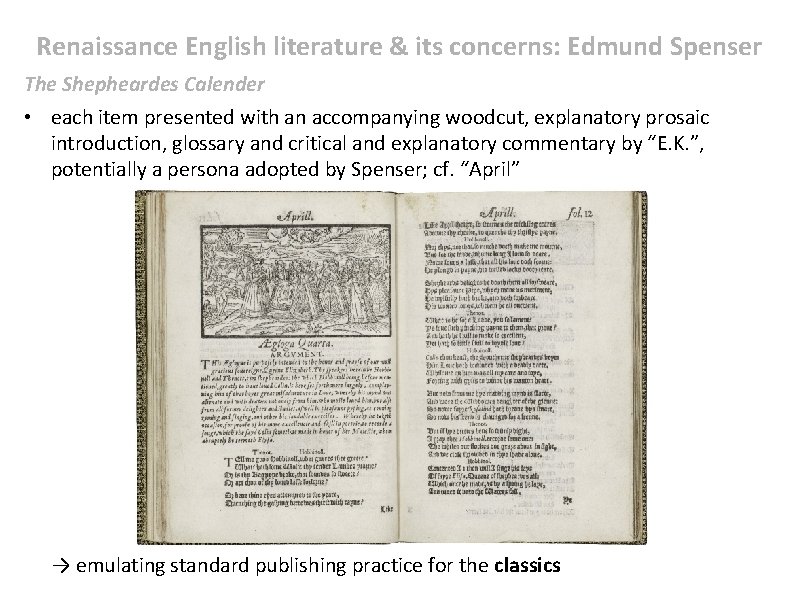

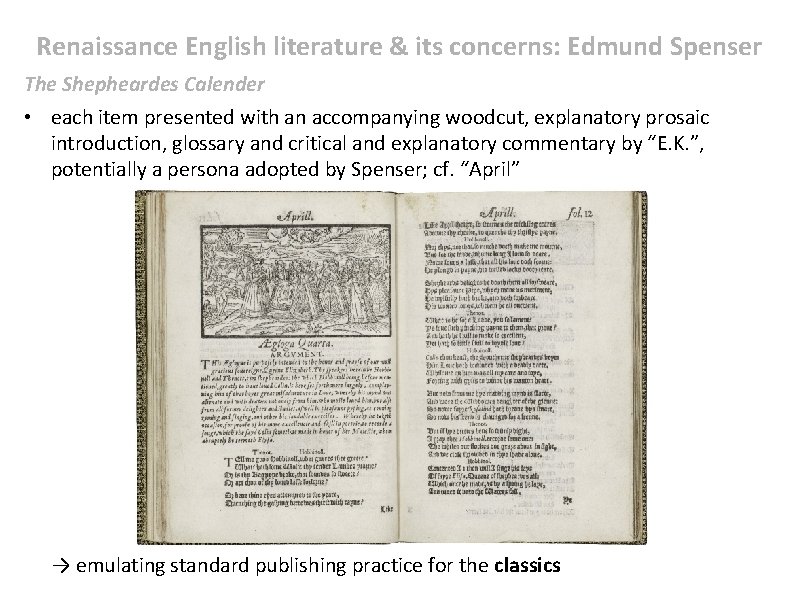

Renaissance English literature & its concerns: Edmund Spenser The Shepheardes Calender • each item presented with an accompanying woodcut, explanatory prosaic introduction, glossary and critical and explanatory commentary by “E. K. ”, potentially a persona adopted by Spenser; cf. “April” → emulating standard publishing practice for the classics

Renaissance English literature & its concerns: Edmund Spenser The Faerie Queene (Books I-III in 1590, Books I-VI in 1596) • the plan announced in the introductory letter was for 12 books (like the Aeneid) • working out a “high style” suitable for epic – use of more “literary” archaisms in keeping with the subject-matter (see below) = romantic epic • written in a new stanzaic form – “Spenserian stanza” (used in Romanticism) (Book I, Canto I) 5 A A gentle knight was pricking (= cantering) on the plain, Upon a great adventure he was bound, 5 B Yclad (=clothed) in mighty arms and silver shield, That greatest Gloriana to him gave 5 A Wherein old dints of deep wounds did remain, (That greatest glorious Queen of Faery Land) 5 B The cruel marks of many a bloody field; To win him worship (=honour), and her grace to have, 5 B Yet arms till that time did he never wield Which of all earthly things he most did crave; 5 C His angry steed did chide his foaming bit, And ever as he rode his heart did yearn 5 B As much disdaining to the curb to yield: To prove his puissance (=power) in battle brave 5 C Full jolly (=gallant) knight he seemed, and fair did sit, Upon his foe, and his new force to learn; 6 C As one for knightly jousts (=tournaments) and fierce encounters fit. Upon his foe, a dragon horrible and stern. But on his breast a bloody cross he bore, The dear remembrance of his dying Lord, For whose sweet sake that glorious badge he wore, And dead, as living, ever him adored: Upon his shield the like was also scored, For sovereign (=most powerful) hope, which in his help he had: Right faithful true he was in deed and word, But of his cheer (=expression) did seem too solemn sad; Yet nothing did he dread, but ever was dreaded.

Renaissance English literature & its concerns: Edmund Spenser The Faerie Queene • models: > classic: epic – Virgil > contemporary Italian: romantic epic (having features of both epic and romance) – Ludovico Ariosto: Orlando Furioso (Raging Roland) = the matter of Charlemagne – Torquato Tasso: La Gierusalemme Liberata (Jerusalem Delivered) = the matter of First Crusade “I have followed all the antique [ancient] poets historical, first Homer who, in the persons of Agamemnon and Ulysses, has ensampled [exemplified] a good governor and a virtuous man: the one in his Iliad, the other in his Odyssey; then Virgil, whose like [similar] intention was to do in the person of Aeneas; after him, Ariosto comprised them both in his Orlando; and lately Tasso dissevered [separated] them again, and formed both parts in two persons, namely that part which they in Philosophy call Ethics, or virtues of a private man, coloured [portrayed] in his Rinaldo: the other, named Politics, in his Godfredo. By example of which excellent poets, I labour to portray in Arthur, before he was king, the image of a brave knight, perfected in the twelve private moral virtues, as Aristotle has devised, which is the purpose of these first twelve books: which if I find to be well accepted, I may be perhaps encouraged to frame the other part of political virtues in his person, after he came to be king. ” → like the classical and unlike the contemporary Italian models, the “project” outlines an epic with a national/imperial dimension: “English epic” “In that Faery Queen I mean glory in my general intention, but in my particular I conceive the most

Renaissance English literature & its concerns: Edmund Spenser The Faerie Queene • exemplary: the protagonist of each book was to embody a specific virtue I – Holiness; II – Temperance; III – Chastity; IV – Friendship; V – Justice; VI - Courtesy • multi-levelled allegory The Redcrosse Knight and his lady Una travel together as he fights the dragon Errour, then separate as the wizard Archimago tricks the Redcrosse Knight in a dream to think that Una is unchaste. After he leaves, the Redcrosse Knight meets Duessa, who feigns distress in order to entrap him. Duessa leads the Redcrosse Knight to captivity by the giant Orgoglio. Meanwhile, Una overcomes peril, meets Arthur, and finally finds the Redcrosse Knight and rescues him from his capture, from Duessa, and from Despair. Una and Arthur help the Redcrosse Knight recover in the House of Holiness, with the House's ruler Caelia and her three daughters joining them; there the Redcrosse Knight sees a vision of his future. He then returns Una to her parents' castle and rescues them from a dragon, and the two are betrothed after resisting Archimago one last time. → The Redcrosse Knight can represent a Christian Everyman or more specifically, as a figure of St George, England; Una and Duessa then respectively represent true and false religion, or Protestantism and the Catholic Church. • in reality the text often goes beyond/against this professed affirmatory, imperial outline/programme

Renaissance English literature & its concerns: Edmund Spenser The Faerie Queene • in the introduction to Book I Spenser owns to his authorship of The Shepheardes Calender and mimics the pseudo-Virgilian introduction to Aeneid which outlines the progress from the pastoral to the epic: Lo I, the man whose Muse whilom (=formerly) did mask (=disguise herself), As time her taught, in lowly shepherd's weeds (=clothes), Am now enforced (=compelled), a far unfitter task, For trumpets stern to change my oaten reeds (=reed pipes), And sing of knights' and ladies' gentle deeds; Whose praises, having slept in silence long, Me, all too mean (=unworthy), the sacred Muse areads (=instructs) To blazon (=proclaim) broad (=far) amongst her learned throng: Fierce wars and faithful loves shall moralize my song.

Bibliography: Andrew Hadfield, ed. , The Cambridge companion to Spenser, Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, 2001 Arthur F. Kinney, ed. The Cambridge companion to English literature, 1500 -1600, Cambridge & New York: Cambridge Unversity Press, 2000 Arthur F. Marotti, Manuscript, Print, and the English Renaissance Lyric, Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 2018 Gabriela Schmidt, Elizabethan Translation and Literary Culture, Berlin: De Gruyter, 2013 Chris Stamatakis, Sir Thomas Wyatt and the Rhetoric of Rewriting: 'Turning the Word', Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012 John E. Stevens, Music & Poetry in the Early Tudor Court, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Archive, 1981 Gary F. Waller, English Poetry of the Sixteenth Century, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge 2014

Apa itu preliminaries

Apa itu preliminaries Preliminary material

Preliminary material Apa itu preliminaries

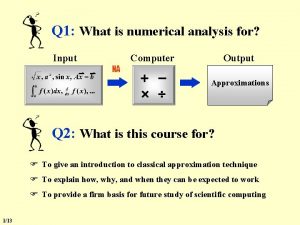

Apa itu preliminaries Mathematical preliminaries in numerical computing

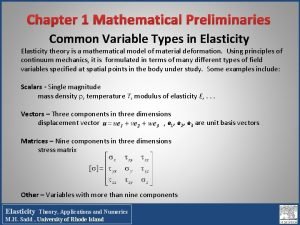

Mathematical preliminaries in numerical computing Chapter 1 mathematical preliminaries

Chapter 1 mathematical preliminaries Destination synoynm

Destination synoynm A paragraph that informs

A paragraph that informs What is an author's purpose

What is an author's purpose Informs annual meeting

Informs annual meeting Which type of essay explains, informs, defines?

Which type of essay explains, informs, defines? Certified analytics professional informs

Certified analytics professional informs Informs marketing science

Informs marketing science Causes of renaissance

Causes of renaissance Italian renaissance vs northern renaissance venn diagram

Italian renaissance vs northern renaissance venn diagram The renaissance outcome renaissance painters/sculptors

The renaissance outcome renaissance painters/sculptors Italian renaissance vs northern renaissance art

Italian renaissance vs northern renaissance art Last supper labeled

Last supper labeled The renaissance introduction to the renaissance answer key

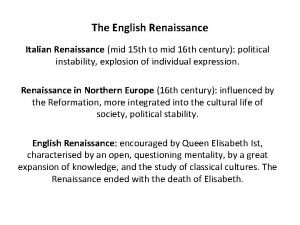

The renaissance introduction to the renaissance answer key Italian renaissance vs english renaissance

Italian renaissance vs english renaissance The renaissance outcome the renaissance in italy

The renaissance outcome the renaissance in italy Physical education during renaissance

Physical education during renaissance Short renaissance poems

Short renaissance poems