Practice placement Case study presentation distal radius DRF

![Biomechanical frame of reference [1] Occupational therapy process Assessment and frames of reference Assessment Biomechanical frame of reference [1] Occupational therapy process Assessment and frames of reference Assessment](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/b8cb3c7ef97013f7ceb9753d3730acfd/image-7.jpg)

![References • Kokaspeles. lv. (2017). Handmade Wooden Toys: The tower of Hanoi. [online] Available References • Kokaspeles. lv. (2017). Handmade Wooden Toys: The tower of Hanoi. [online] Available](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/b8cb3c7ef97013f7ceb9753d3730acfd/image-17.jpg)

- Slides: 19

Practice placement Case study presentation distal radius (DRF) fracture (#) Hand therapy department Year 2 OCT 214 10529913

Placement setting/Role of the Occupational therapist Motivate patient to independently exercise/ restoration of hand function. Hand therapy – non surgical management of hand disorders & physical injuries using physical methods. Work with MDT. Use of the Occupational therapy process [1]. Scar management. Advice on ADLs, assist with emotional/ psychological Holistic, client centered practice [2][3]. [4] support. Patient appointments, clinics, group therapy sessions. Various referrals. Return patient to meaningful participation their daily activities. [1] (Creek, 2003), [2] (Parker, 2011), [3] (IFSHT, 2010), [4] (Islandhandtherapy. com, 2017).

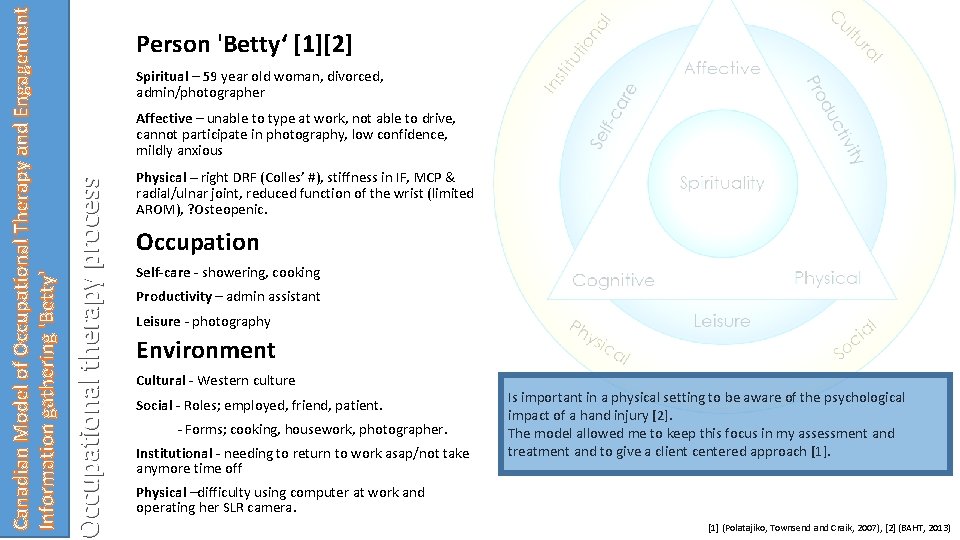

Spiritual – 59 year old woman, divorced, admin/photographer Affective – unable to type at work, not able to drive, cannot participate in photography, low confidence, mildly anxious Occupational therapy process Canadian Model of Occupational Therapy and Engagement Information gathering 'Betty' Person 'Betty‘ [1][2] Physical – right DRF (Colles’ #), stiffness in IF, MCP & radial/ulnar joint, reduced function of the wrist (limited AROM), ? Osteopenic. Occupation Self-care - showering, cooking Productivity – admin assistant Leisure - photography Environment Cultural - Western culture Social - Roles; employed, friend, patient. - Forms; cooking, housework, photographer. Institutional - needing to return to work asap/not take anymore time off Is important in a physical setting to be aware of the psychological impact of a hand injury [2]. The model allowed me to keep this focus in my assessment and treatment and to give a client centered approach [1]. Physical –difficulty using computer at work and operating her SLR camera. [1] (Polatajiko, Townsend and Craik, 2007), [2] (BAHT, 2013)

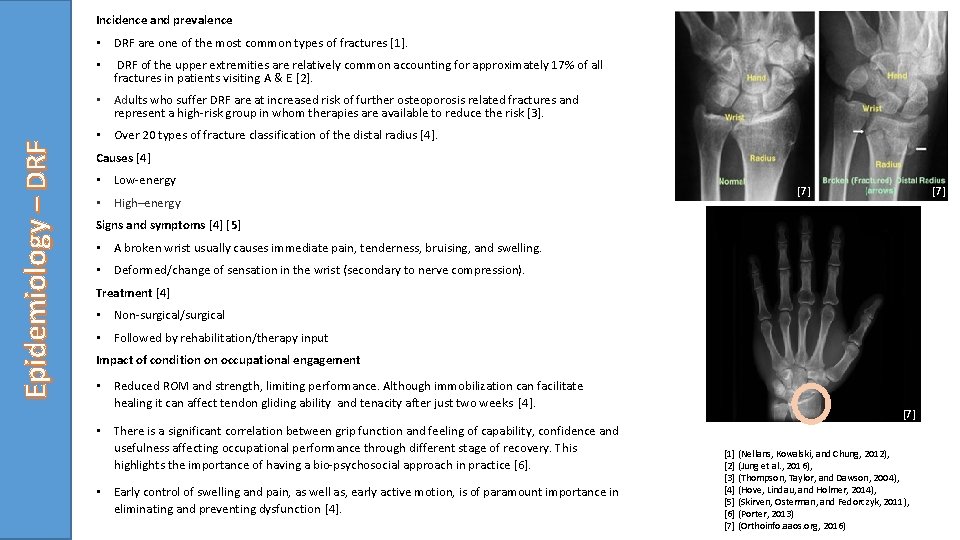

Incidence and prevalence • DRF are one of the most common types of fractures [1]. • DRF of the upper extremities are relatively common accounting for approximately 17% of all fractures in patients visiting A & E [2]. Epidemiology – DRF • Adults who suffer DRF are at increased risk of further osteoporosis related fractures and represent a high-risk group in whom therapies are available to reduce the risk [3]. • Over 20 types of fracture classification of the distal radius [4]. Causes [4] • Low-energy • High–energy [7] [7] Signs and symptoms [4] [5] • A broken wrist usually causes immediate pain, tenderness, bruising, and swelling. • Deformed/change of sensation in the wrist (secondary to nerve compression). Treatment [4] • Non-surgical/surgical • Followed by rehabilitation/therapy input Impact of condition on occupational engagement • Reduced ROM and strength, limiting performance. Although immobilization can facilitate healing it can affect tendon gliding ability and tenacity after just two weeks [4]. • There is a significant correlation between grip function and feeling of capability, confidence and usefulness affecting occupational performance through different stage of recovery. This highlights the importance of having a bio-psychosocial approach in practice [6]. • Early control of swelling and pain, as well as, early active motion, is of paramount importance in eliminating and preventing dysfunction [4]. [7] [1] (Nellans, Kowalski, and Chung, 2012), [7] [2] (Jung et al. , 2016), [3] (Thompson, Taylor, and Dawson, 2004), [4] (Hove, Lindau, and Holmer, 2014), [5] (Skirven, Osterman, and Fedorczyk, 2011), [6] (Porter, 2013) [7] (Orthoinfo. aaos. org, 2016)

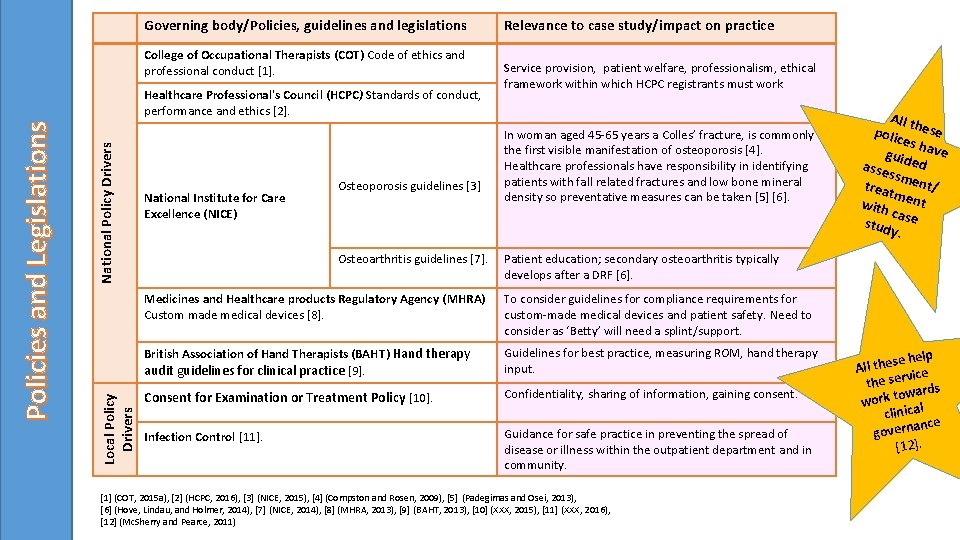

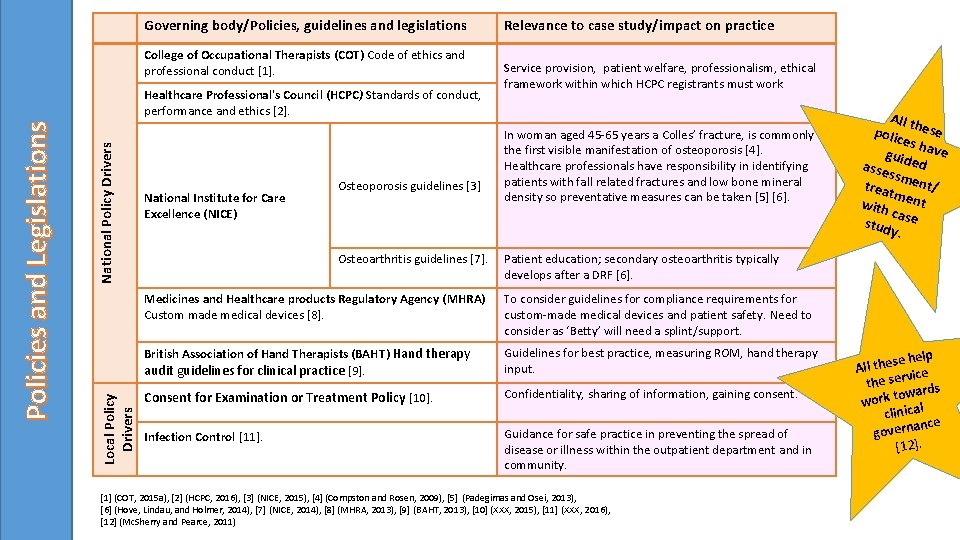

Governing body/Policies, guidelines and legislations College of Occupational Therapists (COT) Code of ethics and professional conduct [1]. National Policy Drivers Local Policy Drivers Policies and Legislations Healthcare Professional's Council (HCPC) Standards of conduct, performance and ethics [2]. National Institute for Care Excellence (NICE) Osteoporosis guidelines [3] Osteoarthritis guidelines [7]. Relevance to case study/impact on practice Service provision, patient welfare, professionalism, ethical framework within which HCPC registrants must work In woman aged 45 -65 years a Colles’ fracture, is commonly the first visible manifestation of osteoporosis [4]. Healthcare professionals have responsibility in identifying patients with fall related fractures and low bone mineral density so preventative measures can be taken [5] [6]. All th polic ese es h guid ave asse ed ssm treat ent/ m with ent ca stud se y. Patient education; secondary osteoarthritis typically develops after a DRF [6]. Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) Custom made medical devices [8]. To consider guidelines for compliance requirements for custom-made medical devices and patient safety. Need to consider as ‘Betty’ will need a splint/support. British Association of Hand Therapists (BAHT) Hand therapy audit guidelines for clinical practice [9]. Guidelines for best practice, measuring ROM, hand therapy input. Consent for Examination or Treatment Policy [10]. Confidentiality, sharing of information, gaining consent. Infection Control [11]. Guidance for safe practice in preventing the spread of disease or illness within the outpatient department and in community. [1] (COT, 2015 a), [2] (HCPC, 2016), [3] (NICE, 2015), [4] (Compston and Rosen, 2009), [5] (Padegimas and Osei, 2013), [6] (Hove, Lindau, and Holmer, 2014), [7] (NICE, 2014), [8] (MHRA, 2013), [9] (BAHT, 2013), [10] (XXX, 2015), [11] (XXX, 2016), [12] (Mc. Sherry and Pearce, 2011) se help e h t l l A vice the ser rds owa work t clinical ance govern [12].

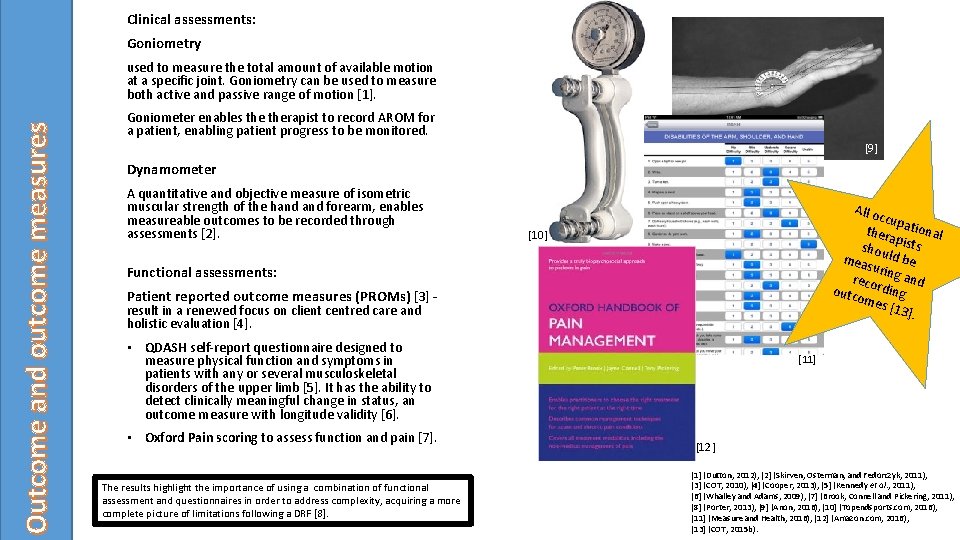

Clinical assessments: Goniometry Outcome and outcome measures used to measure the total amount of available motion at a specific joint. Goniometry can be used to measure both active and passive range of motion [1]. Goniometer enables therapist to record AROM for a patient, enabling patient progress to be monitored. [9] Dynamometer A quantitative and objective measure of isometric muscular strength of the hand forearm, enables measureable outcomes to be recorded through assessments [2]. All o ccup thera ational p shou ists ld b mea surin e reco g and outc rding ome s [13 ]. [10] Functional assessments: Patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) [3] - result in a renewed focus on client centred care and holistic evaluation [4]. • QDASH self-report questionnaire designed to measure physical function and symptoms in patients with any or several musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb [5]. It has the ability to detect clinically meaningful change in status, an outcome measure with longitude validity [6]. • Oxford Pain scoring to assess function and pain [7]. The results highlight the importance of using a combination of functional assessment and questionnaires in order to address complexity, acquiring a more complete picture of limitations following a DRF [8]. [11] [12] [1] (Dutton, 2012), [2] (Skirven, Osterman, and Fedorczyk, 2011), [3] (COT, 2010), [4] (Cooper, 2013), [5] (Kennedy et al. , 2011), [6] (Whalley and Adams, 2009), [7] (Brook, Connell and Pickering, 2011), [8] (Porter, 2013), [9] (Anon, 2016), [10] (Topendsports. com, 2016), [11] (Measure and Health, 2016), [12] (Amazon. com, 2016), [13] (COT, 2015 b).

![Biomechanical frame of reference 1 Occupational therapy process Assessment and frames of reference Assessment Biomechanical frame of reference [1] Occupational therapy process Assessment and frames of reference Assessment](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/b8cb3c7ef97013f7ceb9753d3730acfd/image-7.jpg)

Biomechanical frame of reference [1] Occupational therapy process Assessment and frames of reference Assessment Findings Initial appointment (6 weeks post #) - Skin right hand darker shade red slightly warmer than left - Right more swollen than Left - Radial border, bruised along ulna mid shaft. Left thumb base sore - Pins and Needles along ulnar into hand, muted sensation into finger tips ”like feeling plastic” *Stiffness in RD/UD, limited AROM, ? Reduced tendon glide as • • • Pain Sensory Oedema Movement (Active/Passive) Skin Temperature not able to flex fingers in the cast limited flex/ext of wrist * 2 nd appointment/review (7 weeks post #) Swelling reduced, still muted sensation in all finger tips and distal tip of thumb, bruising significantly reduced, reduced pain, AROM measurements and grip strength recorded 3 rd appointment/review (9 weeks post #) Minimal swelling, still limited AROM – possibly due to non compliance of completing home exercises. Still significant pain on movement – possibly due to reduced tendon glide opposed to joint stiffness. Hand class (10 weeks post #) Attended hand class to focus on improve greater range of movement. Verb al from consent pat gaine ient d thro asse ughout ssm inter ent and vent ion. [1] (Supyk-Mellson and Mc. Kenna, 2010).

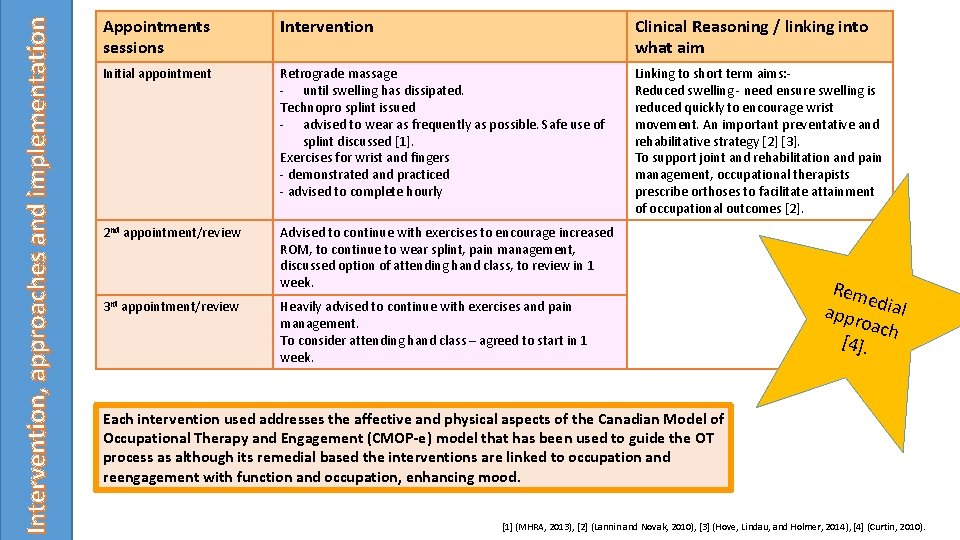

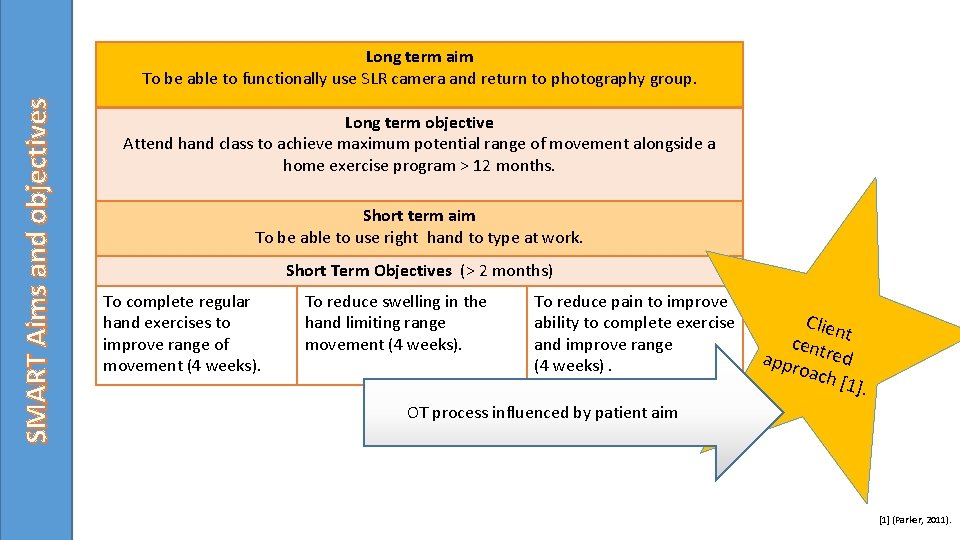

SMART Aims and objectives Long term aim To be able to functionally use SLR camera and return to photography group. Long term objective Attend hand class to achieve maximum potential range of movement alongside a home exercise program > 12 months. Short term aim To be able to use right hand to type at work. Short Term Objectives (> 2 months) To complete regular hand exercises to improve range of movement (4 weeks). To reduce swelling in the hand limiting range movement (4 weeks). To reduce pain to improve ability to complete exercise and improve range (4 weeks). Clien cent t appr red oach [1] . OT process influenced by patient aim [1] (Parker, 2011).

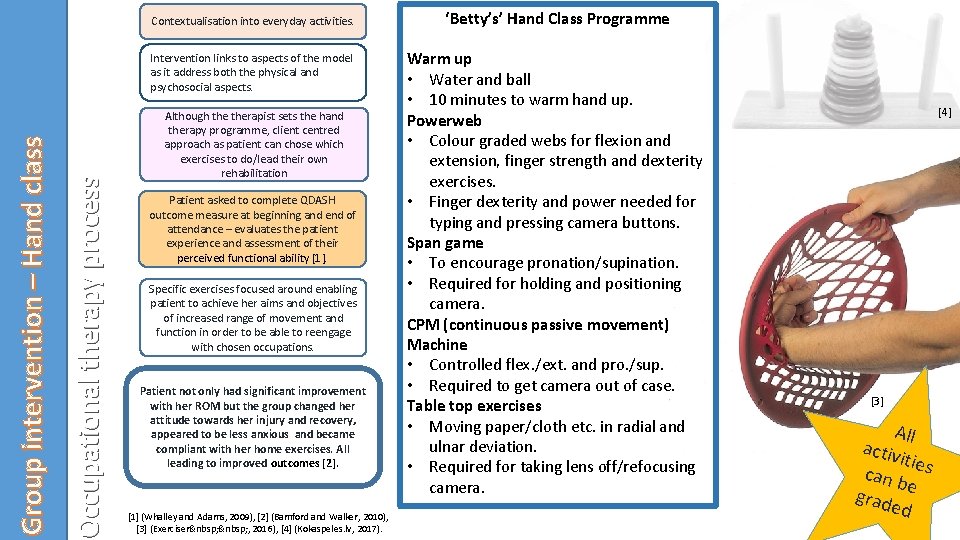

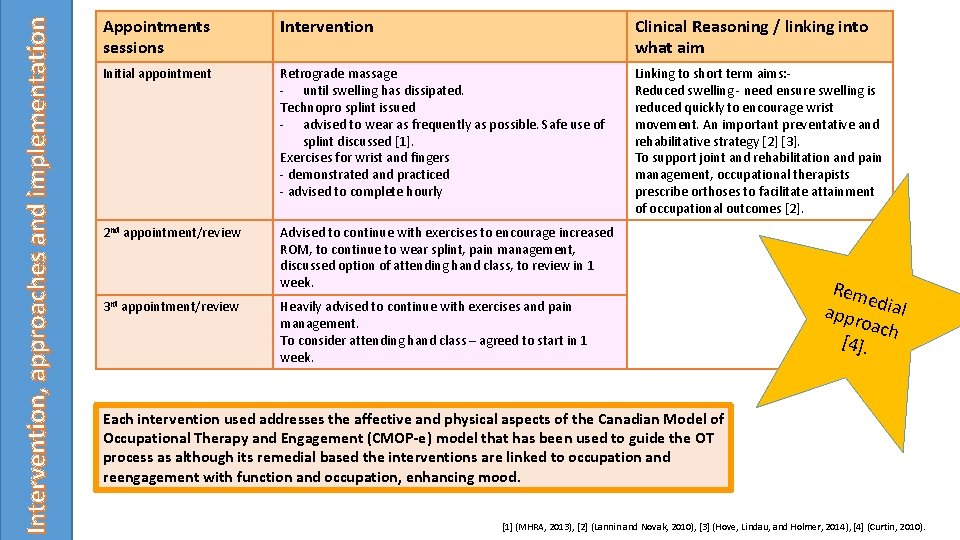

Intervention, approaches and implementation Appointments sessions Intervention Clinical Reasoning / linking into what aim Initial appointment Retrograde massage - until swelling has dissipated. Technopro splint issued - advised to wear as frequently as possible. Safe use of splint discussed [1]. Exercises for wrist and fingers - demonstrated and practiced - advised to complete hourly Linking to short term aims: Reduced swelling - need ensure swelling is reduced quickly to encourage wrist movement. An important preventative and rehabilitative strategy [2] [3]. To support joint and rehabilitation and pain management, occupational therapists prescribe orthoses to facilitate attainment of occupational outcomes [2]. 2 nd appointment/review Advised to continue with exercises to encourage increased ROM, to continue to wear splint, pain management, discussed option of attending hand class, to review in 1 week. 3 rd appointment/review Heavily advised to continue with exercises and pain management. To consider attending hand class – agreed to start in 1 week. Rem e appr dial oach [4]. Each intervention used addresses the affective and physical aspects of the Canadian Model of Occupational Therapy and Engagement (CMOP-e) model that has been used to guide the OT process as although its remedial based the interventions are linked to occupation and reengagement with function and occupation, enhancing mood. [1] (MHRA, 2013), [2] (Lannin and Novak, 2010), [3] (Hove, Lindau, and Holmer, 2014), [4] (Curtin, 2010).

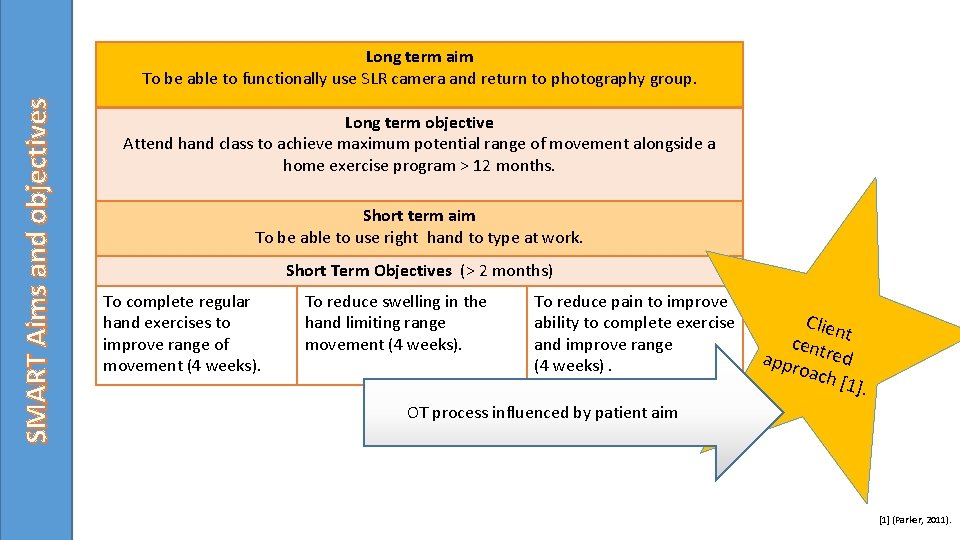

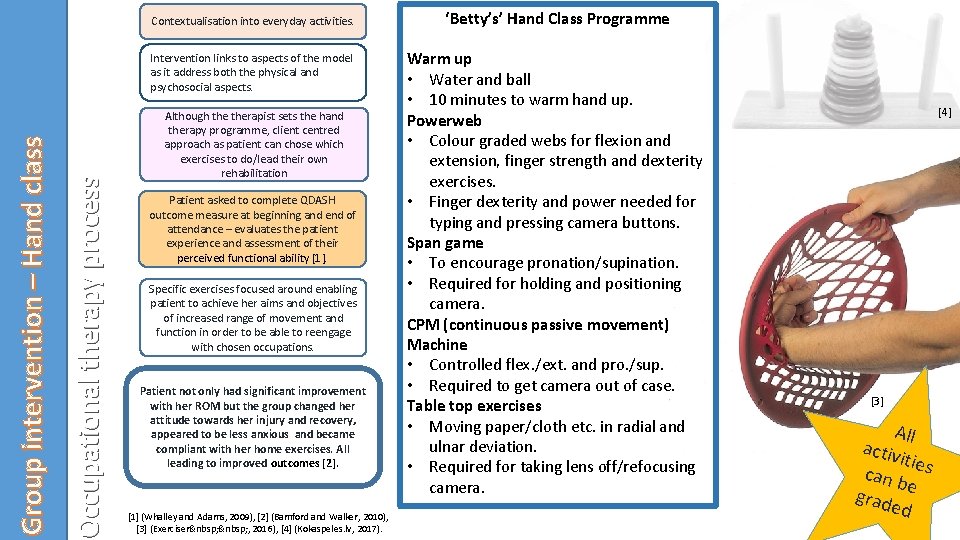

Contextualisation into everyday activities. Occupational therapy process Group intervention – Hand class Intervention links to aspects of the model as it address both the physical and psychosocial aspects. Although therapist sets the hand therapy programme, client centred approach as patient can chose which exercises to do/lead their own rehabilitation Patient asked to complete QDASH outcome measure at beginning and end of attendance – evaluates the patient experience and assessment of their perceived functional ability [1]. Specific exercises focused around enabling patient to achieve her aims and objectives of increased range of movement and function in order to be able to reengage with chosen occupations. Patient not only had significant improvement with her ROM but the group changed her attitude towards her injury and recovery, appeared to be less anxious and became compliant with her home exercises. All leading to improved outcomes [2]. [1] (Whalley and Adams, 2009), [2] (Bamford and Walker, 2010), [3] (Exerciser , 2016), [4] (Kokaspeles. lv, 2017). ‘Betty’s’ Hand Class Programme Warm up • Water and ball • 10 minutes to warm hand up. Powerweb • Colour graded webs for flexion and extension, finger strength and dexterity exercises. • Finger dexterity and power needed for typing and pressing camera buttons. Span game • To encourage pronation/supination. • Required for holding and positioning camera. CPM (continuous passive movement) Machine • Controlled flex. /ext. and pro. /sup. • Required to get camera out of case. Table top exercises • Moving paper/cloth etc. in radial and ulnar deviation. • Required for taking lens off/refocusing camera. [4] [3] All activ iti can b es grad e ed

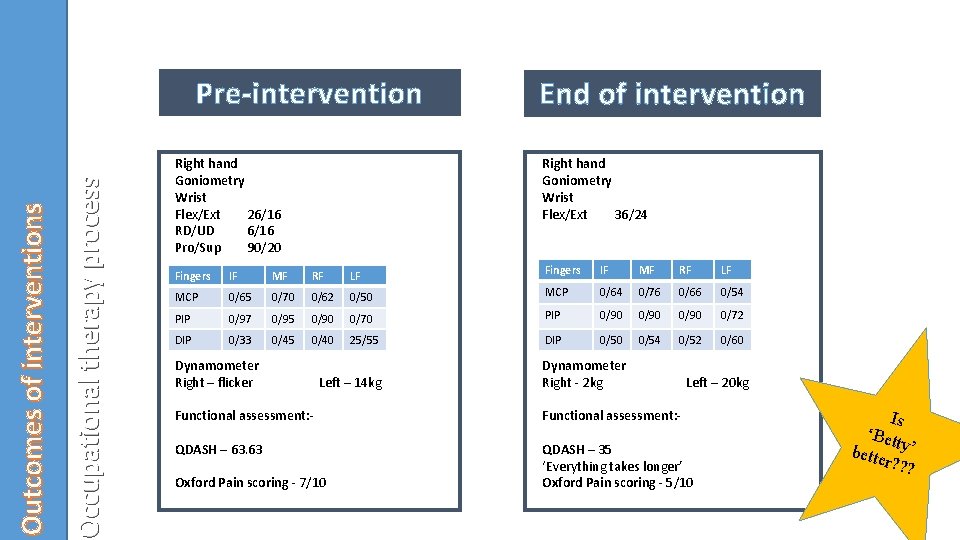

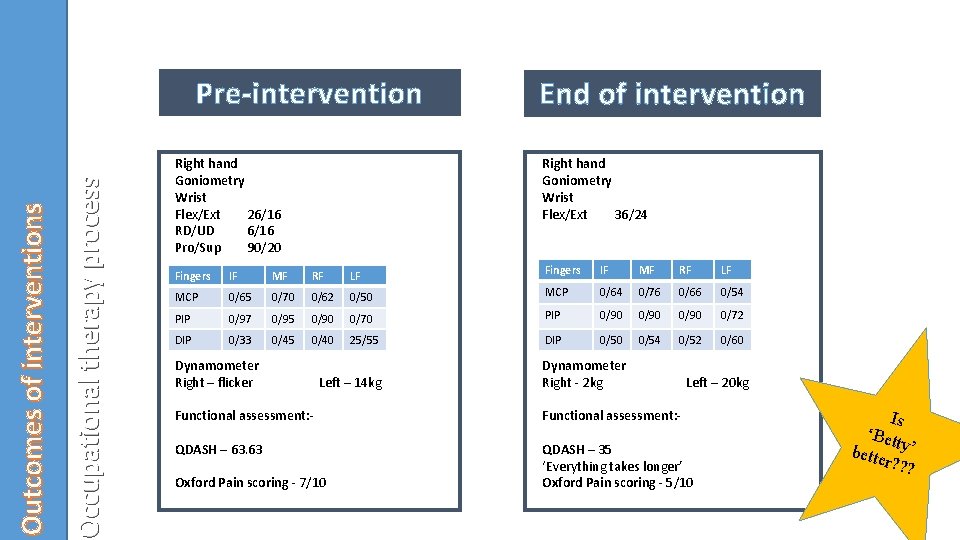

Occupational therapy process Outcomes of interventions Pre-intervention Right hand Goniometry Wrist Flex/Ext 26/16 RD/UD 6/16 Pro/Sup 90/20 End of intervention Right hand Goniometry Wrist Flex/Ext 36/24 Fingers IF MF RF LF MCP 0/65 0/70 0/62 0/50 MCP 0/64 0/76 0/66 0/54 PIP 0/97 0/95 0/90 0/70 PIP 0/90 0/72 DIP 0/33 0/45 0/40 25/55 DIP 0/50 0/54 0/52 0/60 Dynamometer Right – flicker Left – 14 kg Dynamometer Right - 2 kg Left – 20 kg Functional assessment: - QDASH – 63. 63 QDASH – 35 ‘Everything takes longer’ Oxford Pain scoring - 5/10 Oxford Pain scoring - 7/10 Is ‘Bet bette ty’ r? ? ?

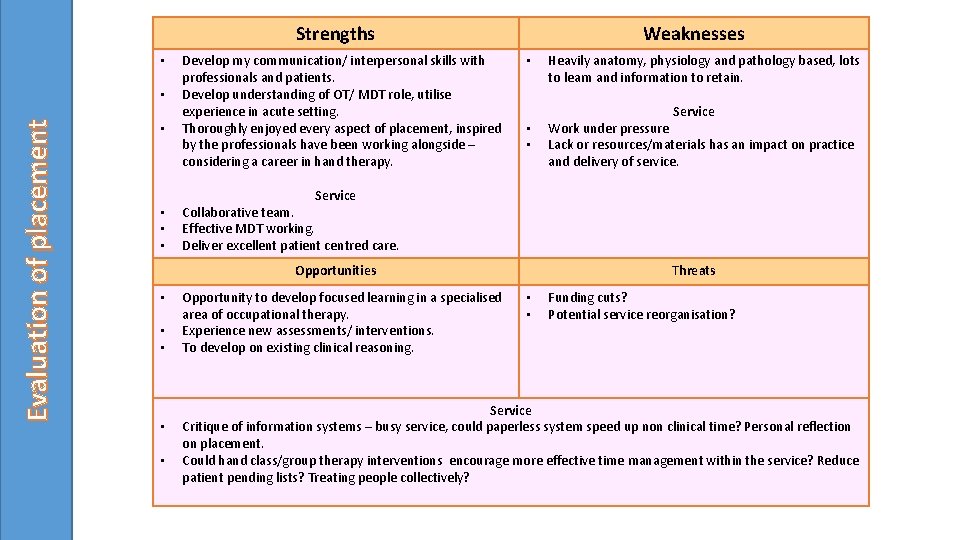

Occupational therapy process End of intervention, discharge End of intervention • At this current time the case study therapeutic input still continues. • The patient will be regularly reviewed to determine how long she needs to attend hand class. • Following a distal radius # rehabilitation can take 6 -12 months to optimise outcomes [1] [2]. Patient safety advice/education on discharge/risk factors Highlight further implications associated with/after obtaining a DRF to patient • prevention of falling is better than cure [1]. • NICE guidelines for Osteoporosis [3] – If the fracture is thought to be a fragility fracture, guidelines recommend FRAX [4] the WHO fracture risk assessment tool predicts an individual’s risk of fracture, providing general clinical guidance for treatment decisions. • Secondary osteoarthritis typically develops after a DRF, follow NICE guidelines for diagnosis of Osteoarthritis [5] and treat/advise accordingly. [1] (Hove, Lindau, and Holmer, 2014), [2] Porter, 2013), [3] ] (NICE, 2015), [4] (Kanis et al. , 2008), [5] ] (NICE, 2014).

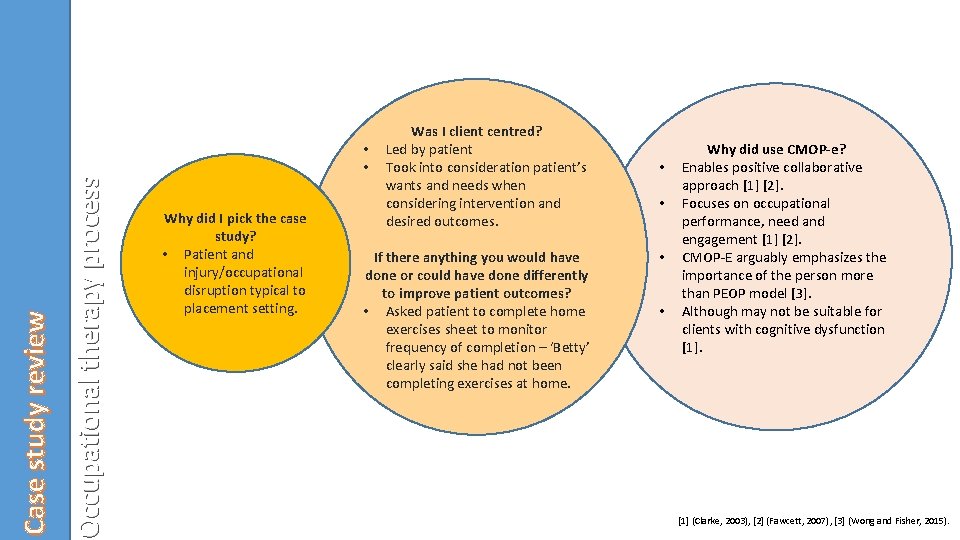

Occupational therapy process Case study review • • Why did I pick the case study? • Patient and injury/occupational disruption typical to placement setting. Was I client centred? Led by patient Took into consideration patient’s wants and needs when considering intervention and desired outcomes. If there anything you would have done or could have done differently to improve patient outcomes? • Asked patient to complete home exercises sheet to monitor frequency of completion – ‘Betty’ clearly said she had not been completing exercises at home. • • Why did use CMOP-e? Enables positive collaborative approach [1] [2]. Focuses on occupational performance, need and engagement [1] [2]. CMOP-E arguably emphasizes the importance of the person more than PEOP model [3]. Although may not be suitable for clients with cognitive dysfunction [1] (Clarke, 2003), [2] (Fawcett, 2007), [3] (Wong and Fisher, 2015).

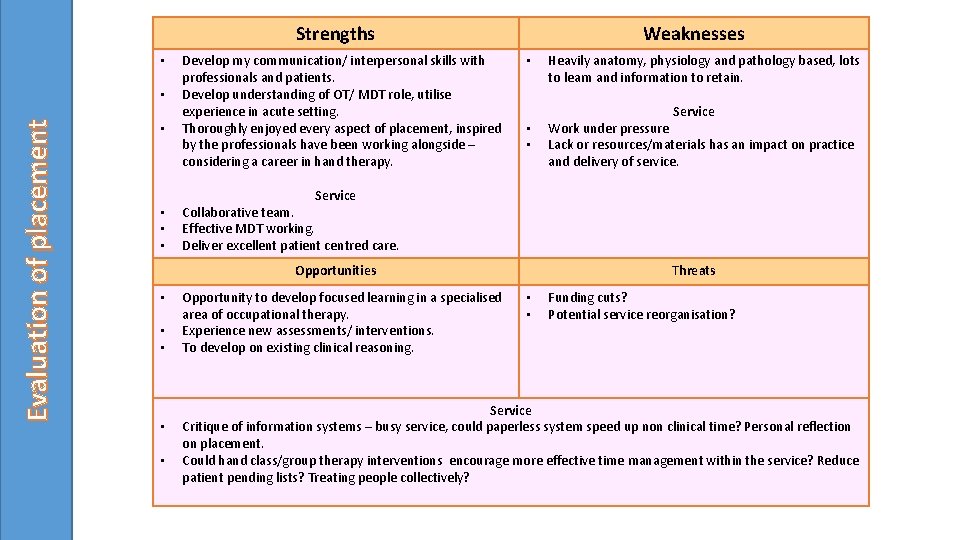

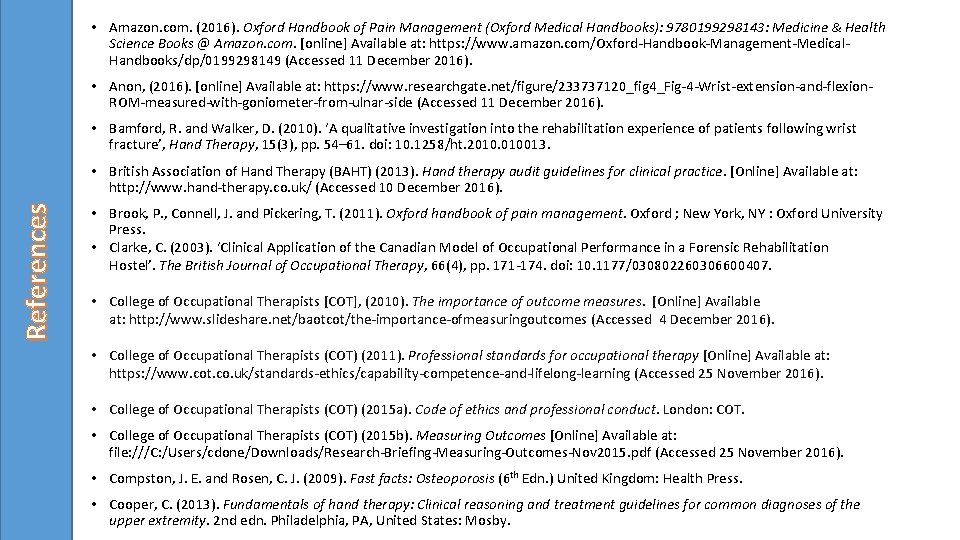

Strengths • Evaluation of placement • • • Develop my communication/ interpersonal skills with professionals and patients. Develop understanding of OT/ MDT role, utilise experience in acute setting. Thoroughly enjoyed every aspect of placement, inspired by the professionals have been working alongside – considering a career in hand therapy. Weaknesses • • Service Work under pressure Lack or resources/materials has an impact on practice and delivery of service. Service Collaborative team. Effective MDT working. Deliver excellent patient centred care. Opportunities • Heavily anatomy, physiology and pathology based, lots to learn and information to retain. Opportunity to develop focused learning in a specialised area of occupational therapy. Experience new assessments/ interventions. To develop on existing clinical reasoning. Threats • • Funding cuts? Potential service reorganisation? Service Critique of information systems – busy service, could paperless system speed up non clinical time? Personal reflection on placement. Could hand class/group therapy interventions encourage more effective time management within the service? Reduce patient pending lists? Treating people collectively?

• Amazon. com. (2016). Oxford Handbook of Pain Management (Oxford Medical Handbooks): 9780199298143: Medicine & Health Science Books @ Amazon. com. [online] Available at: https: //www. amazon. com/Oxford-Handbook-Management-Medical. Handbooks/dp/0199298149 (Accessed 11 December 2016). • Anon, (2016). [online] Available at: https: //www. researchgate. net/figure/233737120_fig 4_Fig-4 -Wrist-extension-and-flexion. ROM-measured-with-goniometer-from-ulnar-side (Accessed 11 December 2016). • Bamford, R. and Walker, D. (2010). ‘A qualitative investigation into the rehabilitation experience of patients following wrist fracture’, Hand Therapy, 15(3), pp. 54– 61. doi: 10. 1258/ht. 2010. 010013. References • British Association of Hand Therapy (BAHT) (2013). Hand therapy audit guidelines for clinical practice. [Online] Available at: http: //www. hand-therapy. co. uk/ (Accessed 10 December 2016). • Brook, P. , Connell, J. and Pickering, T. (2011). Oxford handbook of pain management. Oxford ; New York, NY : Oxford University Press. • Clarke, C. (2003). ‘Clinical Application of the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance in a Forensic Rehabilitation Hostel’. The British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 66(4), pp. 171 -174. doi: 10. 1177/030802260306600407. • College of Occupational Therapists [COT], (2010). The importance of outcome measures. [Online] Available at: http: //www. slideshare. net/baotcot/the-importance-ofmeasuringoutcomes (Accessed 4 December 2016). • College of Occupational Therapists (COT) (2011). Professional standards for occupational therapy [Online] Available at: https: //www. cot. co. uk/standards-ethics/capability-competence-and-lifelong-learning (Accessed 25 November 2016). • College of Occupational Therapists (COT) (2015 a). Code of ethics and professional conduct. London: COT. • College of Occupational Therapists (COT) (2015 b). Measuring Outcomes [Online] Available at: file: ///C: /Users/cdone/Downloads/Research-Briefing-Measuring-Outcomes-Nov 2015. pdf (Accessed 25 November 2016). • Compston, J. E. and Rosen, C. J. (2009). Fast facts: Osteoporosis (6 th Edn. ) United Kingdom: Health Press. • Cooper, C. (2013). Fundamentals of hand therapy: Clinical reasoning and treatment guidelines for common diagnoses of the upper extremity. 2 nd edn. Philadelphia, PA, United States: Mosby.

References • Creek, J. (2003). Occupational therapy defined as a complex intervention. COT: London. [Onlne]. At https: //www. cot. co. uk/publications/occupational-therapy-defined-complex-intervention (Accessed 4 January 2017). • Curtin, M, (2010). ‘Enabling skills and strategies’ in: Curtin, M. (Ed. ), Molineux, M. (Ed. ), Supyk-Mellson, J. (Ed. ) Occupational Therapy and Physical Dysfunction Enabling Occupational Therapy (6 th Edn. ) Edinburgh: Churchill. Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 111 -125. • Dutton, M. (2012). Dutton’s Orthopaedic examination evaluation and intervention (3 rd edn. ) New York: Mc. Graw Hill Medical. • Exerciser , F. (2016). Finger Fitness Power Web Jr. Hand Exerciser. [online] Musician's Friend. Available at: http: //www. musiciansfriend. com/accessories/finger-fitness-power-web-jr. -hand-exerciser (Accessed 11 Dec. 2016). • Fawcett, A. (2007). Principles of assessment and outcome measurement for occupational therapists and physiotherapists. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons. • Handoll, H. and Elliot, J. (2015). Rehabilitation for distal radial fractures in adults [Online] Available at: http: //onlinelibrary. wiley. com/doi/10. 1002/14651858. CD 003324. pub 3/full (Accessed 4 December 2016). • Healthcare Professionals Council (HCPC) (2016). Standards of conduct, performance and ethics [Online] Available at: http: //www. hcpcuk. org/publications/standards/index. asp? id=38 (Accessed 4 December 2016). • Hove, L. M. , Lindau, T. and Holmer, P. (eds. ) (2014). Distal radius fractures: Current concepts. Germany: Springer-Verlag Berlin and Heidelberg Gmb. H & Co. K. International Federation of Societies for Hand Therapy (IFSHT) (2010). IFSHT Hand therapy practice profile [Online] Available at: http: //www. handtherapy. co. uk/index. php? option=com_content&view=article&id=123&Itemid=104 (Accessed 5 January 2017). • • Islandhandtherapy. com. (2017). Island Hand Therapy Clinic: Hand Therapy, Occupational Therapy and Physiotherapy in Victoria British Columbia. [online] Available at: http: //www. islandhandtherapy. com/ [Accessed 6 Jan. 2017]. • Jung, H. J. , Park, H. Y. , Kim, J. S. , Yoon, J. -O. and Jeon, I. -H. (2016). ‘Bone mineral density and prevalence of osteoporosis in Postmenopausal Korean women with low-energy distal radius fractures’, Journal of Korean Medical Science, 31(6), p. 972. doi: 10. 3346/jkms. 2016. 31. 6. 972. • Kanis, J. , Johnell, O. , Oden, A. , Johansson, H. and Mc. Closkey, E. (2008). FRAX™ and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporosis International, 19(4), pp. 385 -397. • Kennedy, C. A. , Beaton, D. E. , Solway, S. , Mc. Connell, S. , and Bombardier, C. (2011). The DASH outcome measure user’s manual. (3 rd ed. ) Toronto: Institute for Work & Health.

![References Kokaspeles lv 2017 Handmade Wooden Toys The tower of Hanoi online Available References • Kokaspeles. lv. (2017). Handmade Wooden Toys: The tower of Hanoi. [online] Available](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/b8cb3c7ef97013f7ceb9753d3730acfd/image-17.jpg)

References • Kokaspeles. lv. (2017). Handmade Wooden Toys: The tower of Hanoi. [online] Available at: http: //kokaspeles. lv/en/categories/logics/the-tower-of-hanoi (Accessed 4 January 2017). • Lannin, N. and Novak, I. (2010). ‘Orthotics for occupational outcomes’ in: Curtin, M. (Ed. ), Molineux, M. (Ed. ), Supyk-Mellson, J. (Ed. ) Occupational Therapy and Physical Dysfunction Enabling Occupational Therapy (6 th Edn. ) Edinburgh: Churchill. Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 507 -526. • Mc. Sherry, R. and Pearce, P. (2011). Clinical Governance. 1 st ed. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. • Measure, D. and Health, I. (2016). DASH Outcome Measure on the App Store. [online] App Store. Available at: https: //itunes. apple. com/us/app/dash-outcome-measure/id 656696682? mt=8 (Accessed 11 December 2016). • Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) (2013 ). Custom made medical devices [Online] Available at: https: //www. gov. uk/government/publications/custom-made-medical-devices (Accessed 4 December 2016). • National Institution of Care Excellence (NICE) (2014). Osteoarthritis: Care and management [Online] Available at: https: //www. nice. org. uk/guidance/cg 177/chapter/1 -recommendations ( Accessed 4 December 2016). • National Institution of Care Excellence (NICE) (2015 ). Osteoporosis: assessing the risk of fragility fracture [Online] Available at: https: //www. nice. org. uk/researchrecommendation/frax-and-qfracture-in-adults-with-secondary-causes-of-osteoporosis-what-is-the -utility-of-frax-and-qfracture-in-detecting-risk-of-fragility-fracture-in-adults-with-secondary-causes-of-osteoporosis ( Accessed 4 December 2016). • Nellans, K. W. , Kowalski, E. and Chung, K. C. (2012). ‘The Epidemiology of distal radius fractures’, Hand Clinics, 28(2), pp. 113– 125. doi: 10. 1016/j. hcl. 2012. 001. • Orthoinfo. aaos. org. (2016). Distal Radius Fractures (Broken Wrist)-Ortho. Info - AAOS. [online] Available at: http: //orthoinfo. aaos. org/topic. cfm? topic=a 00412 (Accessed 11 Dec. 2016). • Padegimas, E. M. and Osei, D. A. (2013). ‘Evaluation and treatment of osetoporotic distal radius fracture in the elderly patient’, Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 6(1), pp. 41– 46. doi: 10. 1007/s 12178 -012 -9153 -8.

References • Parker, D. M. (2011). ‘The client centred frame of reference’ in Duncan, E. A. S. , (ed. ) Foundations for practice in occupational therapy. Bookshelf [Online]. Available at: https: //bookshelf. vitalsource. com/#/books/9780702046612/cfi/6/6[; vnd. vst. idref=B 978 -0 -7020 -32325. 00026 -8]!/4/2[B 978 -0 -7020 -3232 -5. 00026 -8] (Accessed 4 December 2016). • Polatajiko, H. J. , Townsend, E. A. and Craik, J. (2007). Canadian Model of Occupational Performance and Engagement (CMOP-E) in Townsend, E. A. and Polatajiko, H. J. (Eds. ) Enabling occupation II: Advancing and occupational therapy vision of health, wellbeing & justice through occupation. Ottawa, ON: CAOT Publications ACE. Pp. 22 -36. • Porter, S. (2013). ‘Occupational performance and grip function following distal radius fracture: A longitudinal study over a six-month period’, Hand Therapy, 18(4), pp. 118– 128. doi: 10. 1177/1758998313512280. • Skirven, T. M. , Osterman, L. A. and Fedorczyk, J. (2011). Rehabilitation of the hand upper extremity, 2 -Volume set: Expert consult: Online and print. 6 th edn. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Science Health Science div. • Supyk-Mellson, J. and Mc. Kenna, J. (2010). ‘Understanding models of practice’ ’ in: Curtin, M. (Ed. ), Molineux, M. (Ed. ), Supyk-Mellson, J. (Ed. ) Occupational Therapy and Physical Dysfunction Enabling Occupational Therapy (6 th Edn. ) Edinburgh: Churchill. Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 67 -79. • Thompson, P. W. , Taylor, J. and Dawson, A. (2004 ). ‘The annual incidence and seasonal variation of fractures of the distal radius in men and women over 25 years in Dorset, UK’, Injury, 35(5), pp. 462– 466. doi: 10. 1016/s 0020 -1383(03)00117 -7. • Topendsports. com. (2016). About Handgrip Dynamometers. [online] Available at: http: //www. topendsports. com/testing/products/gripdynamometer/ (Accessed 11 Dec. 2016). • Whalley, K. and Adams, J. (2009). ‘The longitudinal validity of the quick and full version of the disability of the arm shoulder and hand questionnaire in musculoskeletal hand outpatients’, Hand Therapy, 14(1), pp. 22– 25. doi: 10. 1258/ht. 2009. 009003. • Wong, S. and Fisher, G. (2015). Comparing and Using Occupation-Focused Models. Occupational Therapy In Health Care, 29(3), pp. 297 -315. • XXX (2015). Infection Prevention & Control Policy. [Online] Available at: https: //xxxxxxx/a-z/infection-controldocuments/? opentab=1 (Accessed 10 December 2016). • XXX (2016). Consent for Examination or Treatment Policy. [Online] Available at: https: //xxxxxxx/easysiteweb/getresource. axd? assetid=3077&type=0&servicetype=1 (Accessed 10 December 2016).

Any questions? ?