Narrative Writing Why do we tell stories Narrative

- Slides: 38

Narrative Writing Why do we tell stories?

Narrative Assessment Components • Using context clues to determine time periods • Citing evidence that supports author’s opinion • Compare and contrast author’s perception of people in her life • Identifying author’s main epiphany/truth/belief • Know your literary terms! • Simile • Metaphor • Allusion • Personification

“One Million Volumes” page 128 As you read, determine Anaya’s driving belief/truth/epiphany behind his narrative.

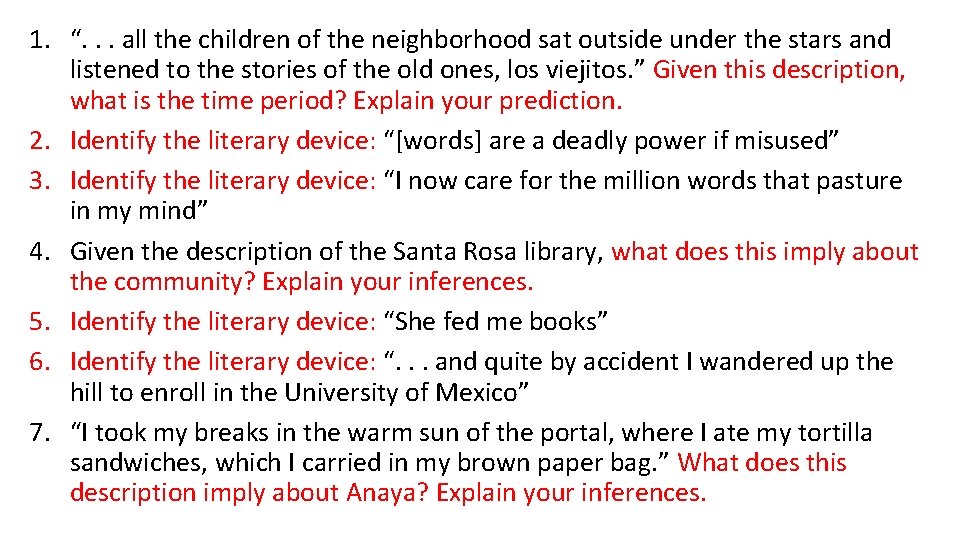

1. “. . . all the children of the neighborhood sat outside under the stars and listened to the stories of the old ones, los viejitos. ” Given this description, what is the time period? Explain your prediction. 2. Identify the literary device: “[words] are a deadly power if misused” 3. Identify the literary device: “I now care for the million words that pasture in my mind” 4. Given the description of the Santa Rosa library, what does this imply about the community? Explain your inferences. 5. Identify the literary device: “She fed me books” 6. Identify the literary device: “. . . and quite by accident I wandered up the hill to enroll in the University of Mexico” 7. “I took my breaks in the warm sun of the portal, where I ate my tortilla sandwiches, which I carried in my brown paper bag. ” What does this description imply about Anaya? Explain your inferences.

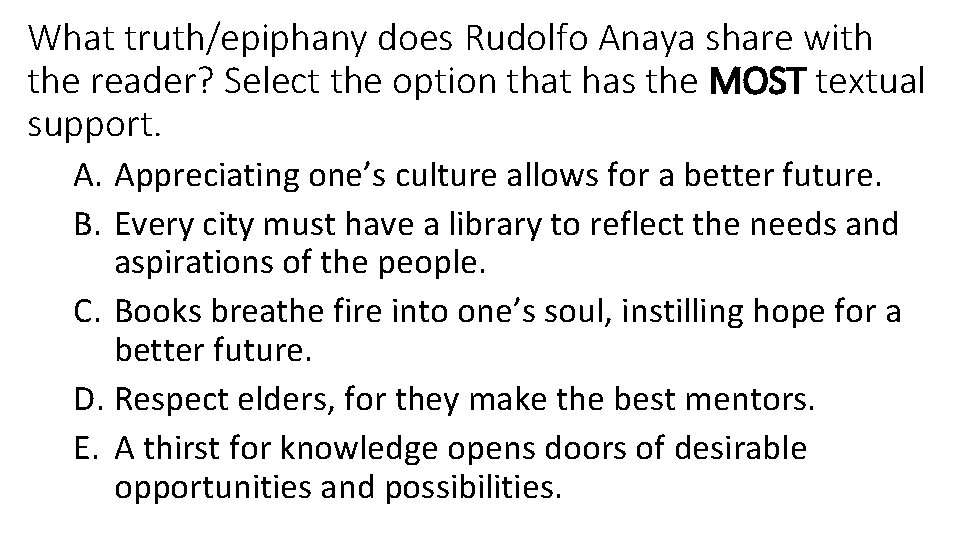

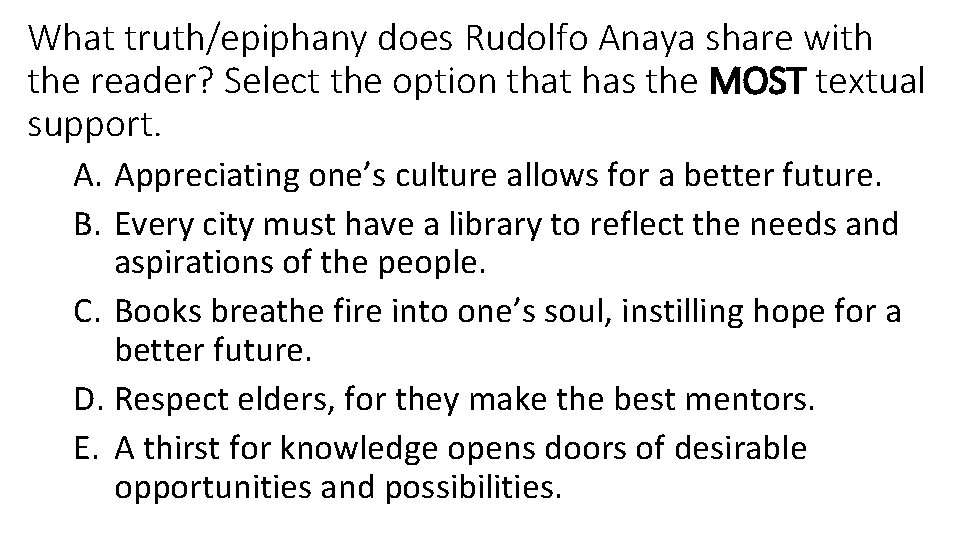

What truth/epiphany does Rudolfo Anaya share with the reader? Select the option that has the MOST textual support. A. Appreciating one’s culture allows for a better future. B. Every city must have a library to reflect the needs and aspirations of the people. C. Books breathe fire into one’s soul, instilling hope for a better future. D. Respect elders, for they make the best mentors. E. A thirst for knowledge opens doors of desirable opportunities and possibilities.

Note: Do not write a persuasive argument or take a stand on a controversial issue. Think in terms of personal philosophy, not current controversies. I believe gun rights should be protected.

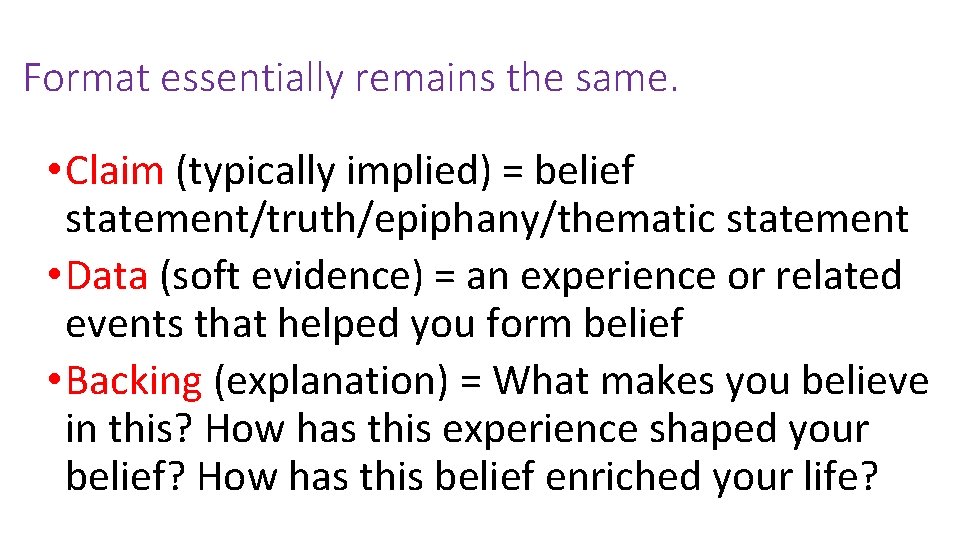

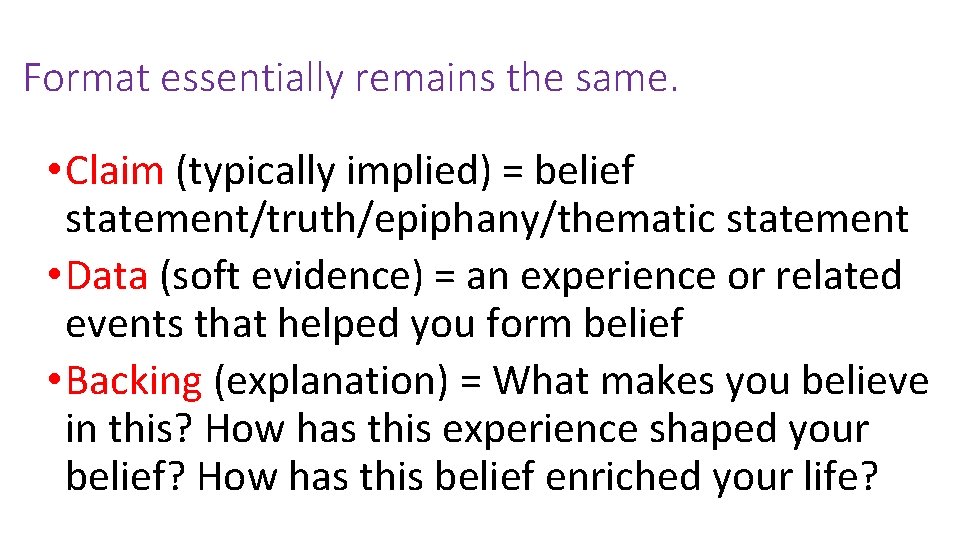

Format essentially remains the same. • Claim (typically implied) = belief statement/truth/epiphany/thematic statement • Data (soft evidence) = an experience or related events that helped you form belief • Backing (explanation) = What makes you believe in this? How has this experience shaped your belief? How has this belief enriched your life?

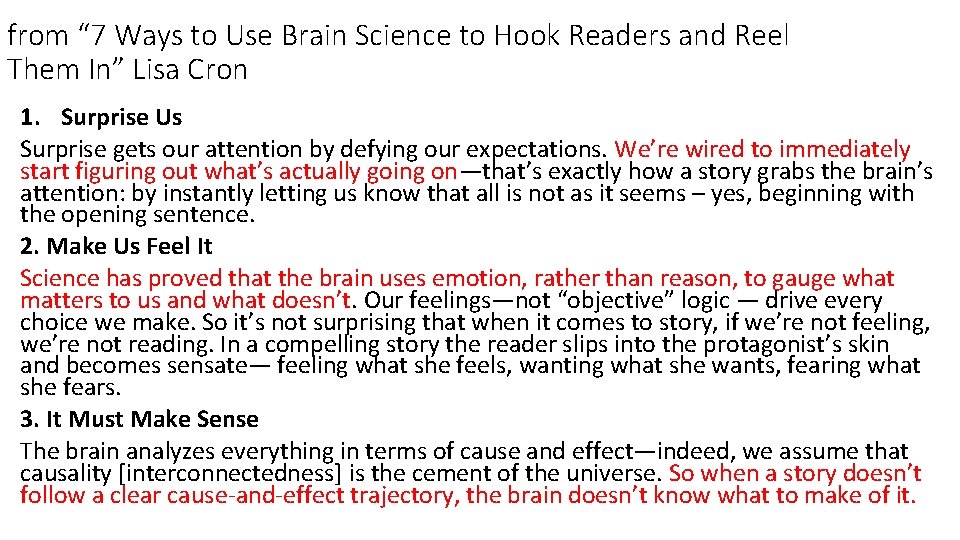

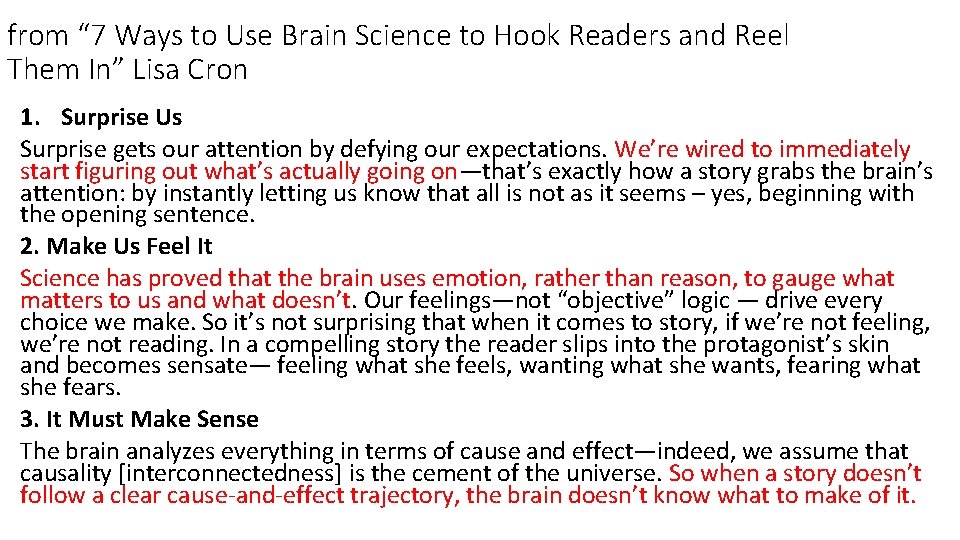

from “ 7 Ways to Use Brain Science to Hook Readers and Reel Them In” Lisa Cron 1. Surprise Us Surprise gets our attention by defying our expectations. We’re wired to immediately start figuring out what’s actually going on—that’s exactly how a story grabs the brain’s attention: by instantly letting us know that all is not as it seems – yes, beginning with the opening sentence. 2. Make Us Feel It Science has proved that the brain uses emotion, rather than reason, to gauge what matters to us and what doesn’t. Our feelings—not “objective” logic — drive every choice we make. So it’s not surprising that when it comes to story, if we’re not feeling, we’re not reading. In a compelling story the reader slips into the protagonist’s skin and becomes sensate— feeling what she feels, wanting what she wants, fearing what she fears. 3. It Must Make Sense The brain analyzes everything in terms of cause and effect—indeed, we assume that causality [interconnectedness] is the cement of the universe. So when a story doesn’t follow a clear cause-and-effect trajectory, the brain doesn’t know what to make of it.

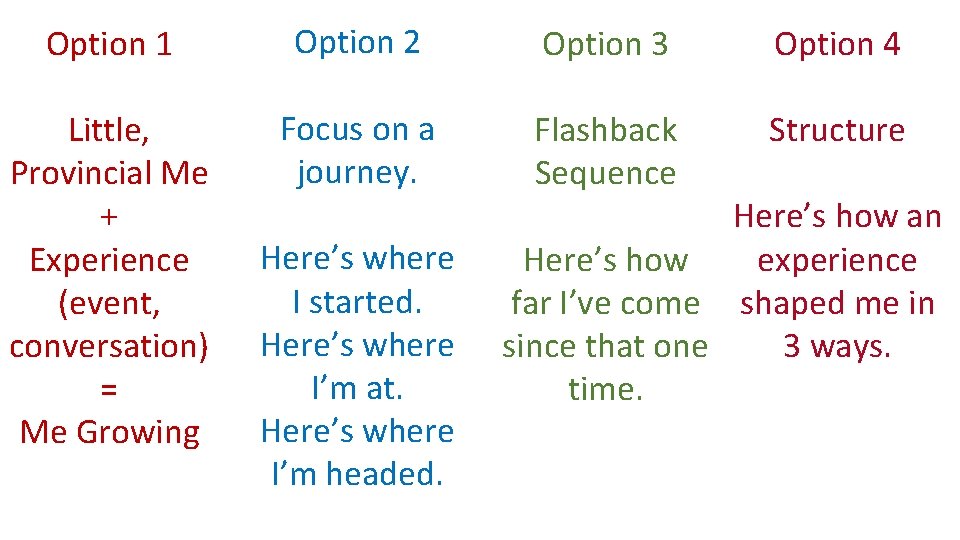

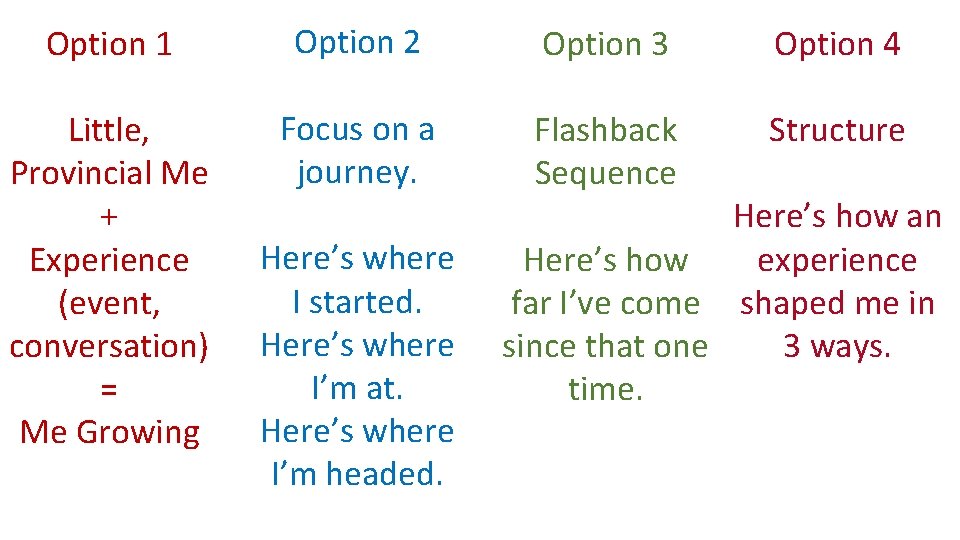

Option 1 Option 2 Option 3 Option 4 Little, Provincial Me + Experience (event, conversation) = Me Growing Focus on a journey. Flashback Sequence Structure Here’s where I started. Here’s where I’m at. Here’s where I’m headed. Here’s how an Here’s how experience far I’ve come shaped me in since that one 3 ways. time.

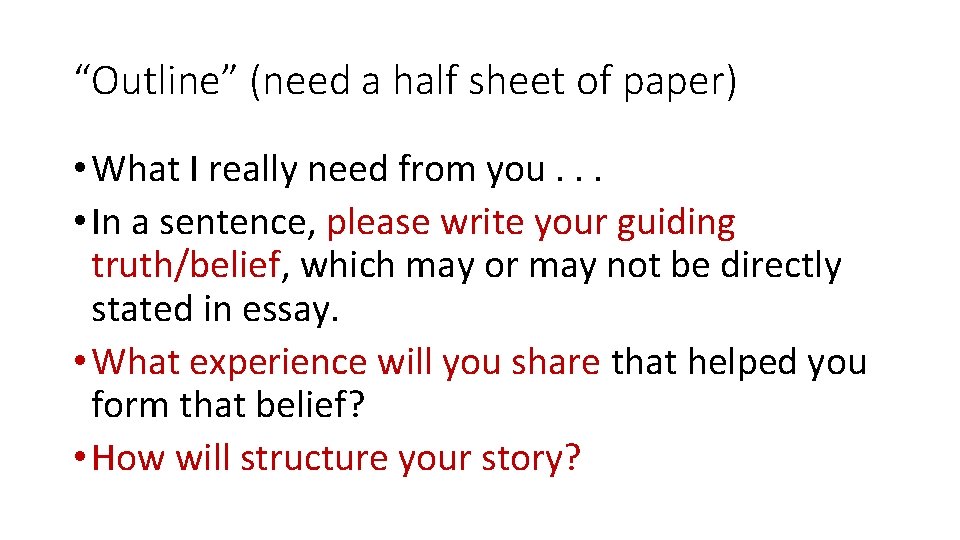

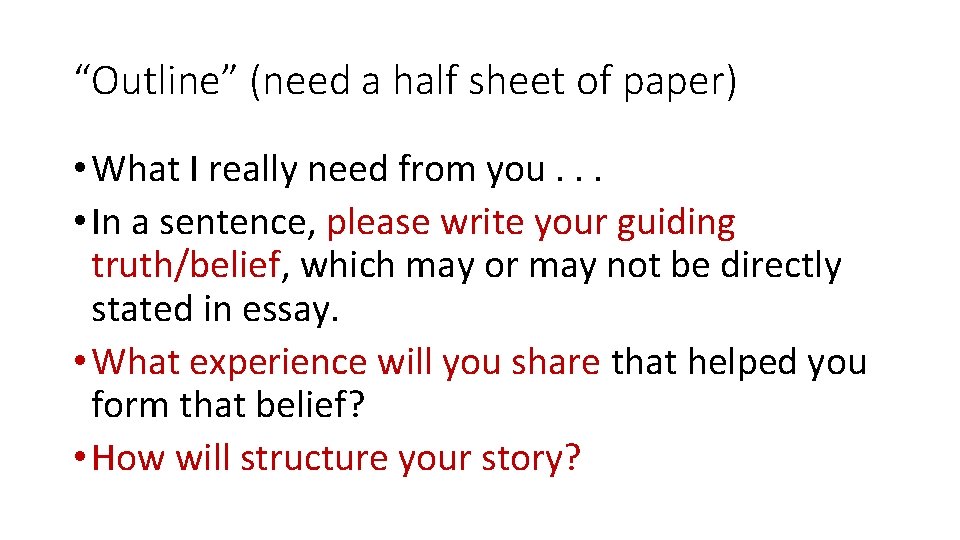

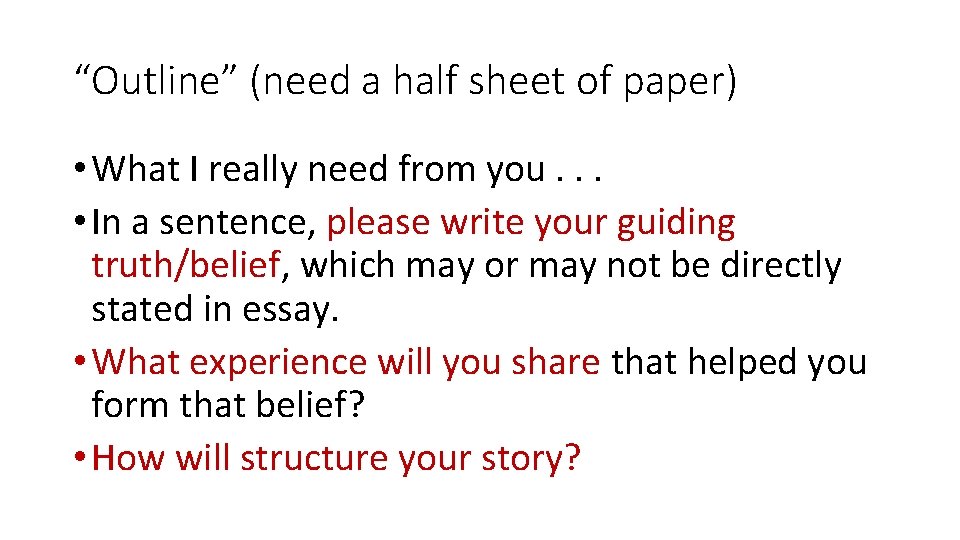

“Outline” (need a half sheet of paper) • What I really need from you. . . • In a sentence, please write your guiding truth/belief, which may or may not be directly stated in essay. • What experience will you share that helped you form that belief? • How will structure your story?

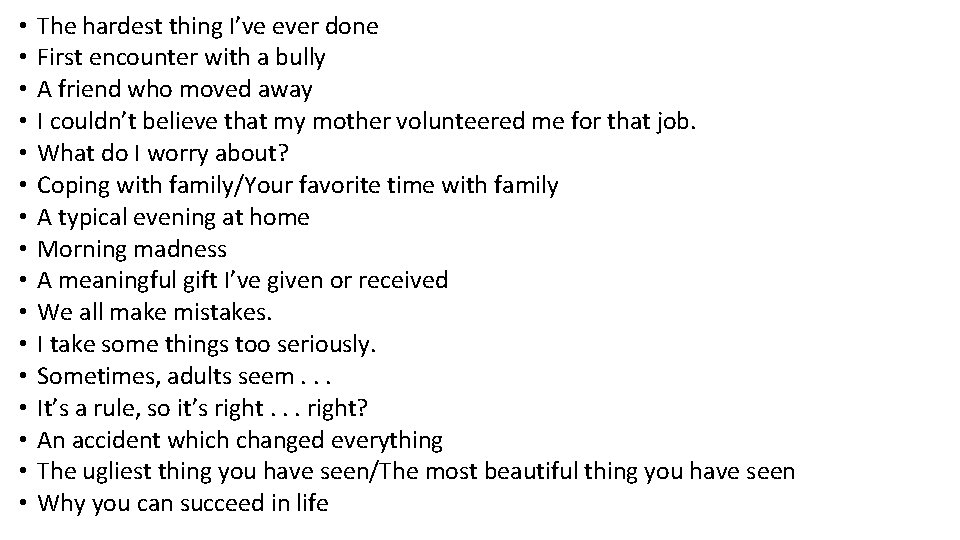

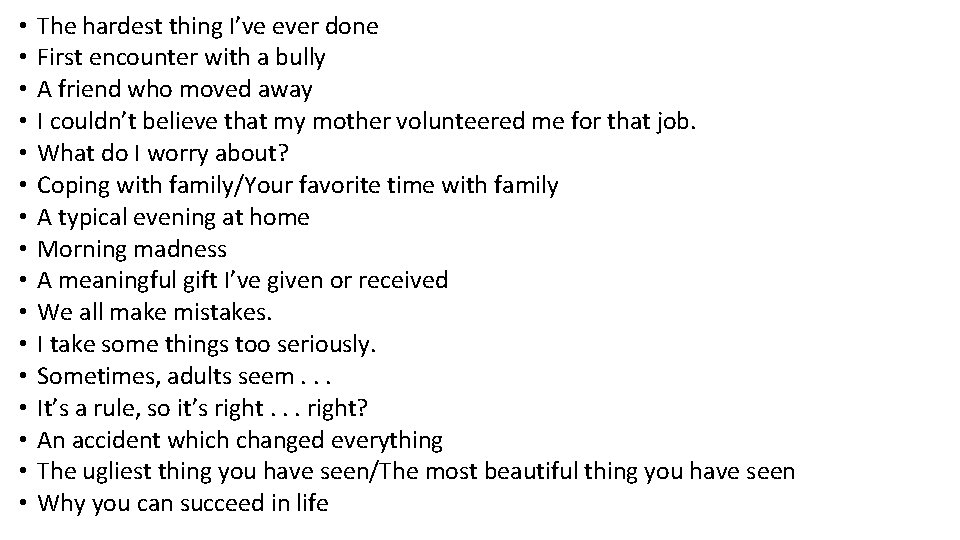

• • • • The hardest thing I’ve ever done First encounter with a bully A friend who moved away I couldn’t believe that my mother volunteered me for that job. What do I worry about? Coping with family/Your favorite time with family A typical evening at home Morning madness A meaningful gift I’ve given or received We all make mistakes. I take some things too seriously. Sometimes, adults seem. . . It’s a rule, so it’s right. . . right? An accident which changed everything The ugliest thing you have seen/The most beautiful thing you have seen Why you can succeed in life

Take a silent walk.

Describe the weather outside. • It is nice. • It is windy. • It is cold. • This is all telling when you need to show this. • How do I know what you consider a nice day? Show me.

Show, Not Tell by R. Michael Burns

• Narrative is all about forging an emotional link between the author and the reader. • While many a great piece of fiction functions on a high intellectual level, the good stuff almost always works, first and foremost, viscerally. • One of the best ways to do this is by creating vivid images that immerse readers in the world of the narrator — by not merely telling readers what’s happening, but showing it to them.

Let the reader see it. • Telling merely catalogs actions and emotions; showing creates images in a reader’s imagination. • Bob felt scared. • This is unambiguous, but not at all evocative — Bob may feel fear, but the reader isn’t likely to. • Bob’s face went ashen. His breathing came in ragged gasps. • This creates a distinct picture in the reader’s mind. As an added bonus, it also gives us a bit of insight into how frightened Bob is and how he handles his fear.

“Let’s go!” Mary said impatiently. “Let’s go!” Mary snapped.

Use strong verbs. • He walked down the street. • This gives us the basics, but it’s bland. Contrast this with. . . • He ambled down the street. • He swaggered down the street. • He skulked down the street. • He shuffled down the street. • You can see the impact a good verb has. Each version creates a significantly different image.

Ethel wrote her name messily on the line.

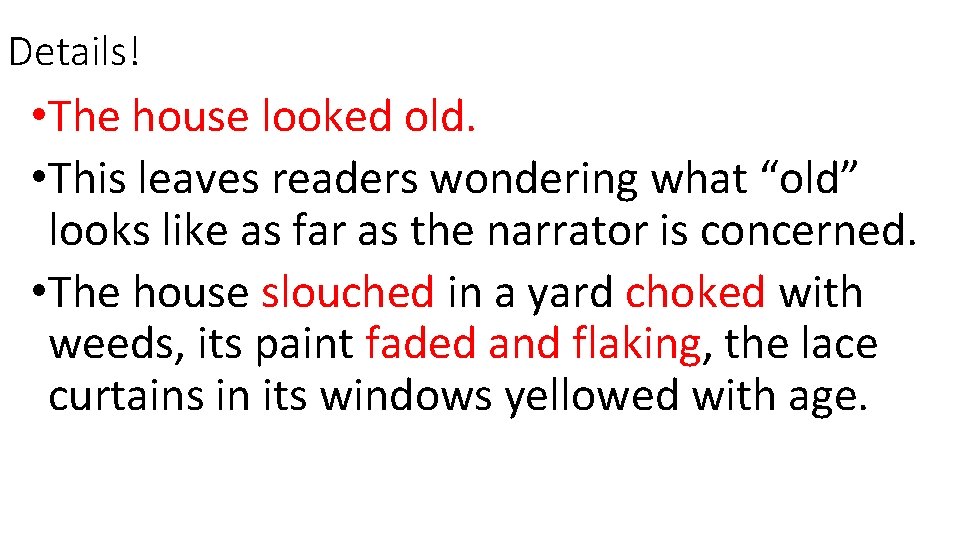

Details! • The house looked old. • This leaves readers wondering what “old” looks like as far as the narrator is concerned. • The house slouched in a yard choked with weeds, its paint faded and flaking, the lace curtains in its windows yellowed with age.

The content of dialogue is a useful “showing” tool. It can give readers insight into a character’s intelligence and level of sophistication, can hint at background and even suggest something about self-image. DIALOGUE

Write down a simple, telling sentence. She was nervous. He refused to answer the question. I was surprised.

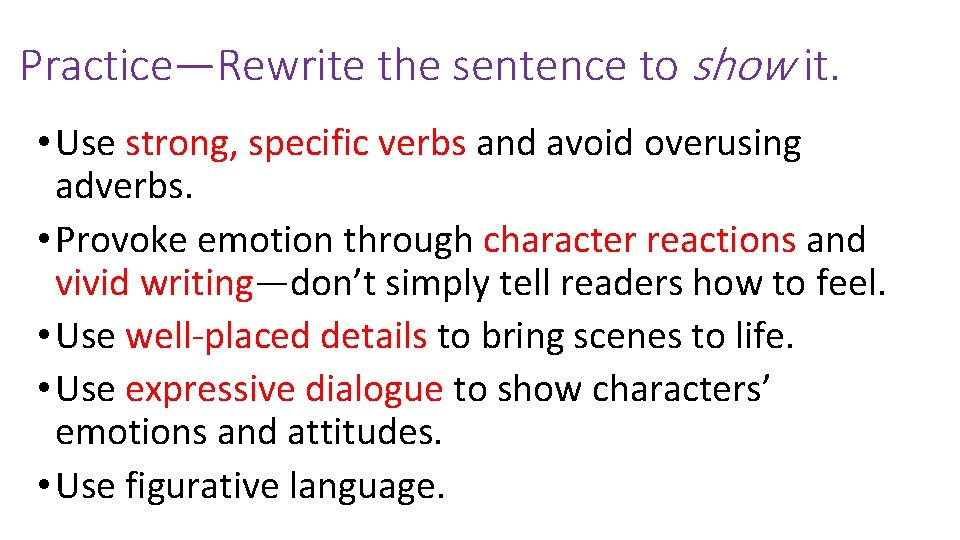

Practice—Rewrite the sentence to show it. • Use strong, specific verbs and avoid overusing adverbs. • Provoke emotion through character reactions and vivid writing—don’t simply tell readers how to feel. • Use well-placed details to bring scenes to life. • Use expressive dialogue to show characters’ emotions and attitudes. • Use figurative language.

Show, Not Tell • Game after game, I sat on the sidelines, watching my love of football get pounded into the ground. I was like the deflated ball, capable of soaring if only someone would reach out to help me. • “I hate you , I hate you!” My little brother fumed, running out the front door. I would have gone after him had I known a car was coming down the street the moment he flew out the door, but this fight was like any other.

Reflective Essay • The difference between an “A” and “B” on this comes down to. . . • Obvious effort and thought—the writer really tried to help the reader understand his or her belief/truth/epiphany • Use of strong verbs, descriptions, and figurative language to intensify main truth. • Let me show you something, NOT let me tell you something

Good hook sentences say, “Drop everything you’re doing and read me right now, ” without actually coming out and just saying that.

A good hook sentence must be consistent with your writing! You can’t just write an awesome sentence because it’s awesome and then go off onto another topic entirely.

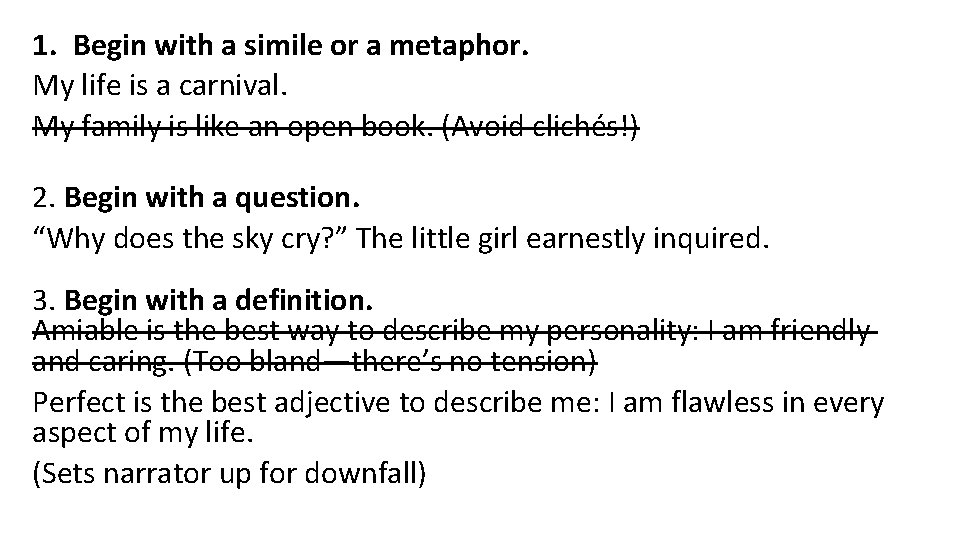

1. Begin with a simile or a metaphor. My life is a carnival. My family is like an open book. (Avoid clichés!) 2. Begin with a question. “Why does the sky cry? ” The little girl earnestly inquired. 3. Begin with a definition. Amiable is the best way to describe my personality: I am friendly and caring. (Too bland—there’s no tension) Perfect is the best adjective to describe me: I am flawless in every aspect of my life. (Sets narrator up for downfall)

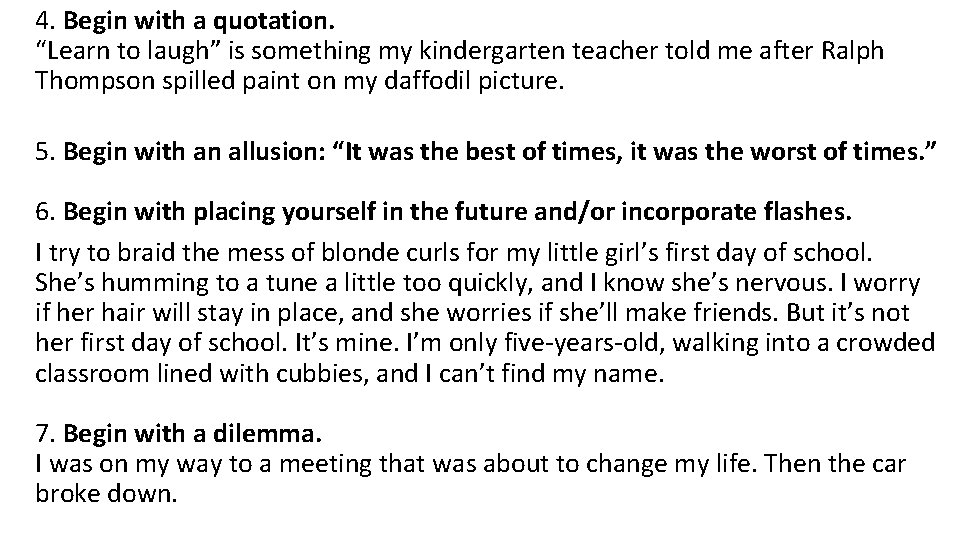

4. Begin with a quotation. “Learn to laugh” is something my kindergarten teacher told me after Ralph Thompson spilled paint on my daffodil picture. 5. Begin with an allusion: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. ” 6. Begin with placing yourself in the future and/or incorporate flashes. I try to braid the mess of blonde curls for my little girl’s first day of school. She’s humming to a tune a little too quickly, and I know she’s nervous. I worry if her hair will stay in place, and she worries if she’ll make friends. But it’s not her first day of school. It’s mine. I’m only five-years-old, walking into a crowded classroom lined with cubbies, and I can’t find my name. 7. Begin with a dilemma. I was on my way to a meeting that was about to change my life. Then the car broke down.

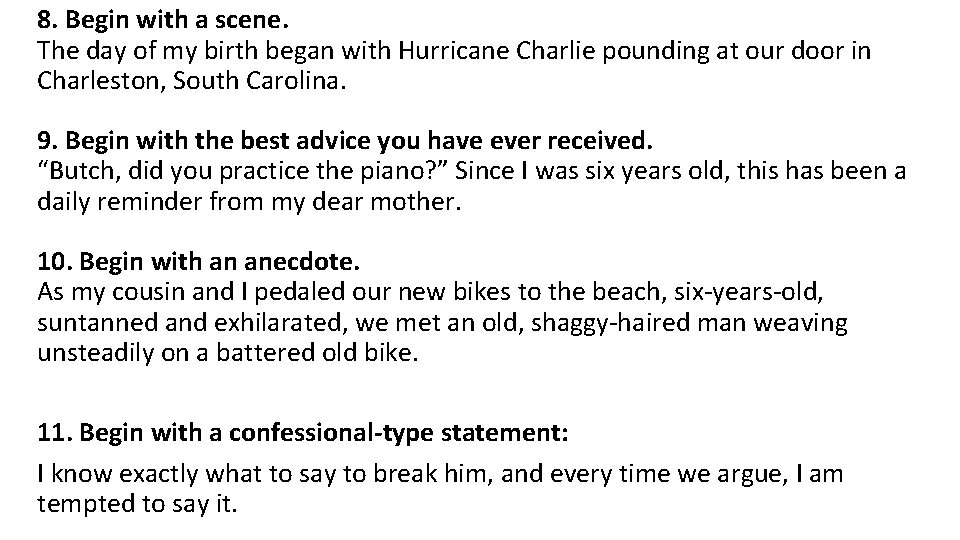

8. Begin with a scene. The day of my birth began with Hurricane Charlie pounding at our door in Charleston, South Carolina. 9. Begin with the best advice you have ever received. “Butch, did you practice the piano? ” Since I was six years old, this has been a daily reminder from my dear mother. 10. Begin with an anecdote. As my cousin and I pedaled our new bikes to the beach, six-years-old, suntanned and exhilarated, we met an old, shaggy-haired man weaving unsteadily on a battered old bike. 11. Begin with a confessional-type statement: I know exactly what to say to break him, and every time we argue, I am tempted to say it.

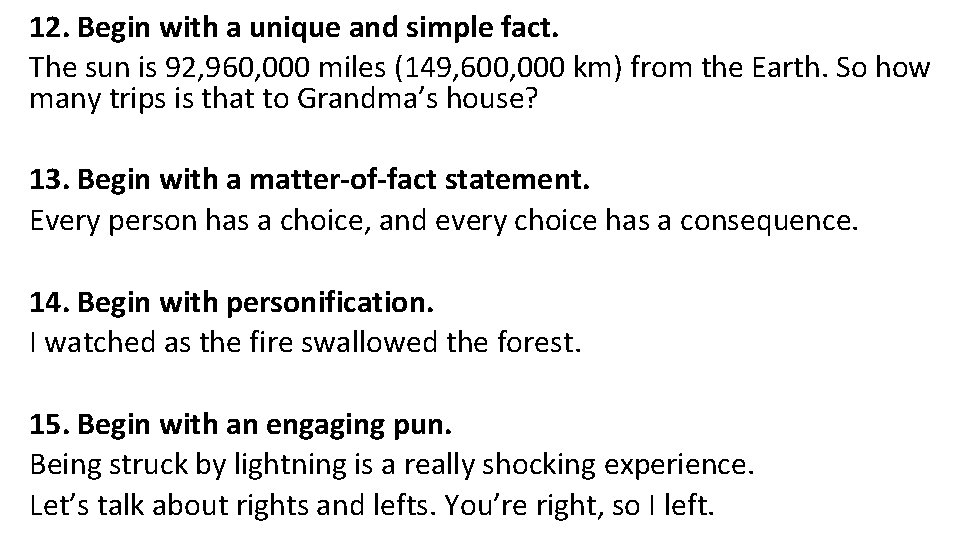

12. Begin with a unique and simple fact. The sun is 92, 960, 000 miles (149, 600, 000 km) from the Earth. So how many trips is that to Grandma’s house? 13. Begin with a matter-of-fact statement. Every person has a choice, and every choice has a consequence. 14. Begin with personification. I watched as the fire swallowed the forest. 15. Begin with an engaging pun. Being struck by lightning is a really shocking experience. Let’s talk about rights and lefts. You’re right, so I left.

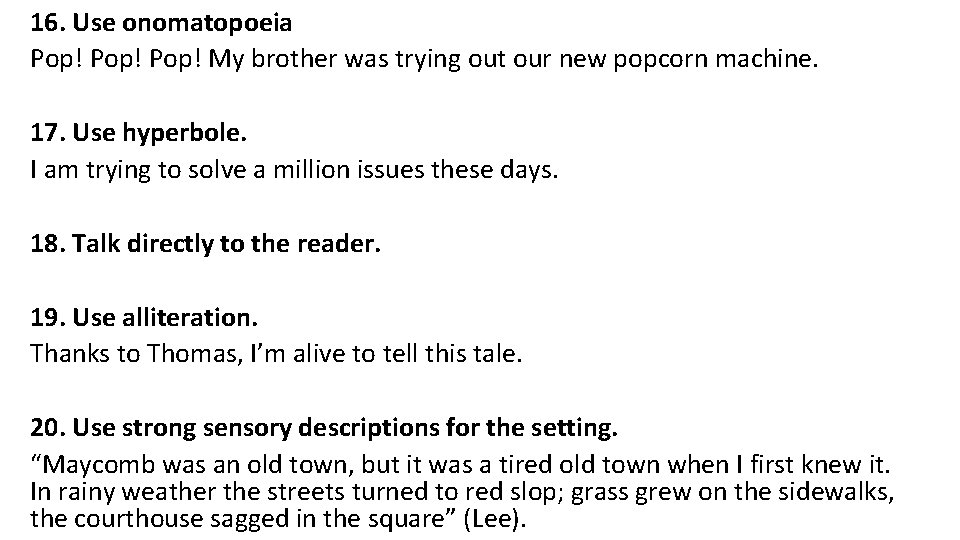

16. Use onomatopoeia Pop! My brother was trying out our new popcorn machine. 17. Use hyperbole. I am trying to solve a million issues these days. 18. Talk directly to the reader. 19. Use alliteration. Thanks to Thomas, I’m alive to tell this tale. 20. Use strong sensory descriptions for the setting. “Maycomb was an old town, but it was a tired old town when I first knew it. In rainy weather the streets turned to red slop; grass grew on the sidewalks, the courthouse sagged in the square” (Lee).

“Outline” (need a half sheet of paper) • What I really need from you. . . • In a sentence, please write your guiding truth/belief, which may or may not be directly stated in essay. • What experience will you share that helped you form that belief? • How will structure your story?

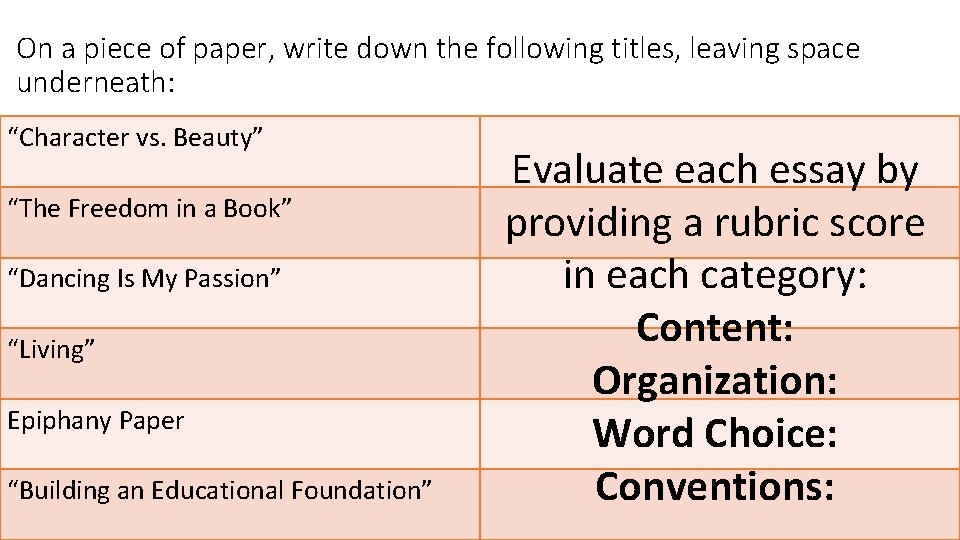

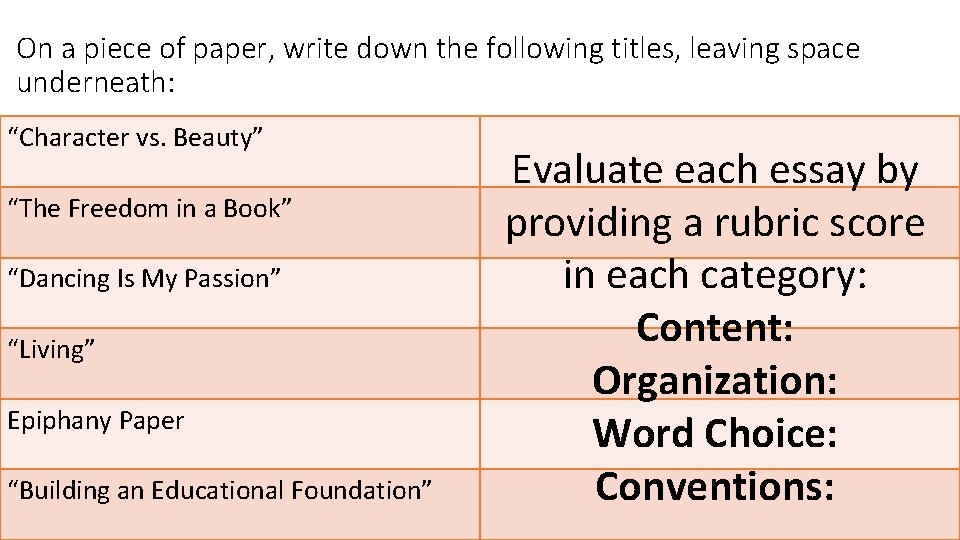

On a piece of paper, write down the following titles, leaving space underneath: “Character vs. Beauty” “The Freedom in a Book” “Dancing Is My Passion” “Living” Epiphany Paper “Building an Educational Foundation” Evaluate each essay by providing a rubric score in each category: Content: Organization: Word Choice: Conventions:

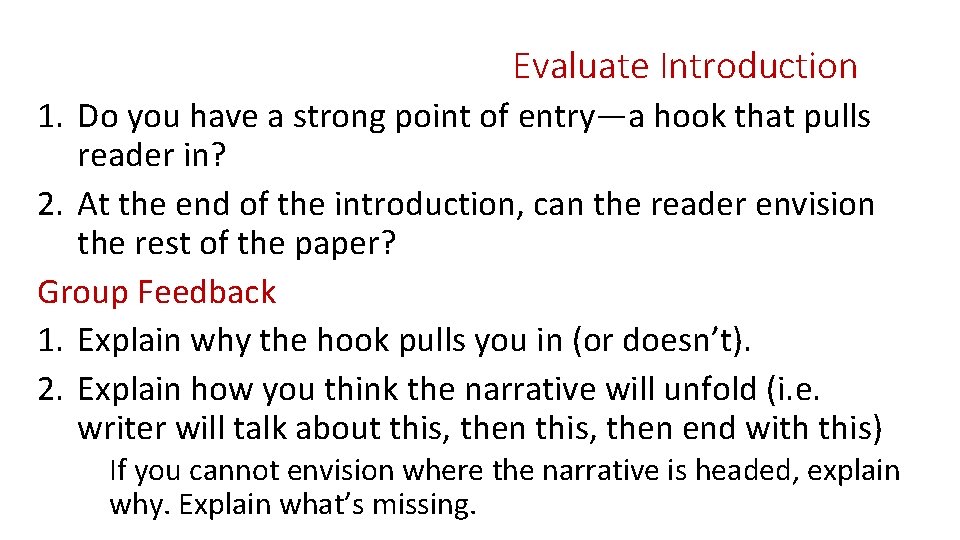

Evaluate Introduction 1. Do you have a strong point of entry—a hook that pulls reader in? 2. At the end of the introduction, can the reader envision the rest of the paper? Group Feedback 1. Explain why the hook pulls you in (or doesn’t). 2. Explain how you think the narrative will unfold (i. e. writer will talk about this, then end with this) If you cannot envision where the narrative is headed, explain why. Explain what’s missing.

Show, not tell • Do you have strong, personalized metaphors and similes? If not, where could you incorporate one? • Often ideas come when strange or contradictory words or phrases are strung together (called paradoxes). It is in the small things we see it. The child's first step, as awesome as an earthquake. Anne Sexton’s “Courage”

Revisions • Circle all your pronouns • Can you replace some of the pronouns with an emotion to personify? • Can you make one of the senses the subject of the sentence? • Can you make a detail of the story as subject of the sentence? • Circle some of your nouns • Do you have strong accompanying adjectives? • Can you attach participial phrases to some of these nouns? • Can you incorporate figures of speech? • Replace weak verbs with strong action verbs. • Incorporate necessary commas and remove unnecessary commas. • Revise run-ons and fragments.