Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Half of a Yellow Sun

![Arguably, war has emerged problematically as the new authenticity out of Africa […. ] Arguably, war has emerged problematically as the new authenticity out of Africa […. ]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/e98cbf6fdcc663e386a4c6ed62d13278/image-26.jpg)

- Slides: 29

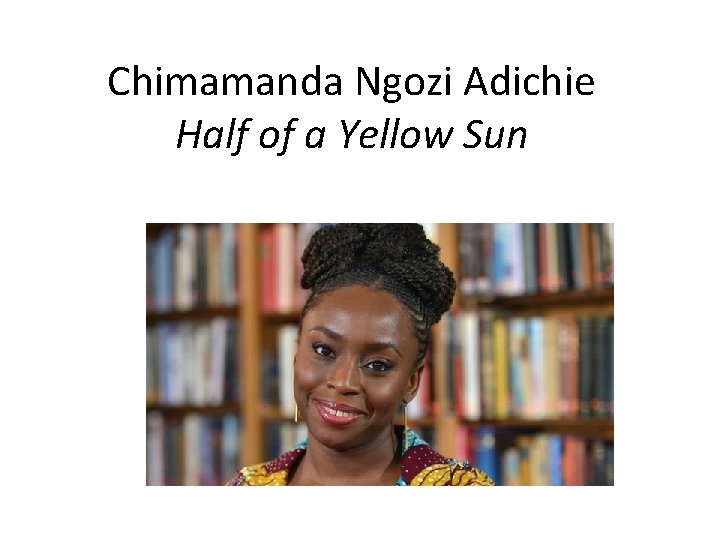

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie Half of a Yellow Sun

Literary genealogies Chinua Achebe

‘Adichie’s relation to her male predecessor, Chinua Achebe, is notable in several respects: she continues his practice of writing as an Igbo and a Nigerian, while maintaining thematic lines of conversation with the United States. She may be the first Nigerian author since Achebe to have comparable international fame at a very young age […. ] her second novel, Half of a Yellow Sun, ends with a literary twist on the conceit of a book within a book, one that echoes the ironical ending of Things Fall apart […. ] The reader’s surprise upon learning of Ugwu’s authorship of the fiction he or she has just consumed parallels the shift of perspective at the end of Things Fall Apart: from the familiar Igbo to the alien British, from Okonkwo to the District Commissioner whose writing constitutes the official view of the world’. (Susan Andrade, ‘Adichie’s Genealogies’)

The Commissioner went away, taking three or four of the soldiers with him. In the many years in which he had toiled to bring civilization to different parts of Africa he had learned a number of things. One of them was that a District Commissioner must never attend to such undignified details as cutting a hanged man from the tree. Such attention would give the natives a poor opinion of him. In the book which he planned to write he would stress that point. As he walked back to the court he thought about that book. Every day brought him some new material. The story of this man who had killed a messenger and hanged himself would make interesting reading. One could almost write a whole chapter on him. Perhaps not a whole chapter but a reasonable paragraph, at any rate. There was so much else to include, and one must be firm in cutting out details. He had already chosen the title of the book, after much thought: The Pacification of the Primitive Tribes of the Lower Niger. (Chinua Achebe, Things Fall Apart)

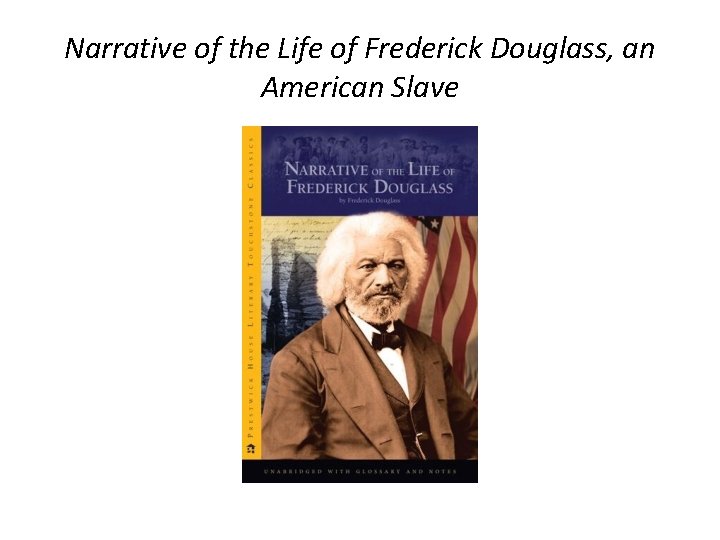

‘Yes, sah. It will be part of a big book. It will take me many more years to finish it and I will call it “Narratives of the Life of a Country”. ’ ‘Very ambitious, ’ Mr Richard said. ‘I wish I had that Frederick Douglass book. ’ (Half of a Yellow Sun, Ch. 35, p. 424)

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave

‘Ugwu gave him the family’s name and address, and Mr Richard wrote it down, and afterwards they were both silent and Ugwu fumbled, awkwardly, for something to say. “Are you still writing your book, sah? ” “No. ” “‘The World Was Silent When We Died’. It is a good title. ” “Yes, it is. It came from something Colonel Madu said once. ” Richard paused. “The war isn’t my story to tell, really. ” Ugwu nodded. He had never thought that it was. ’ (Half of a Yellow Sun, pp. 424 -5)

Biafra flag

Achebe, There Was a Country

Map of Africa

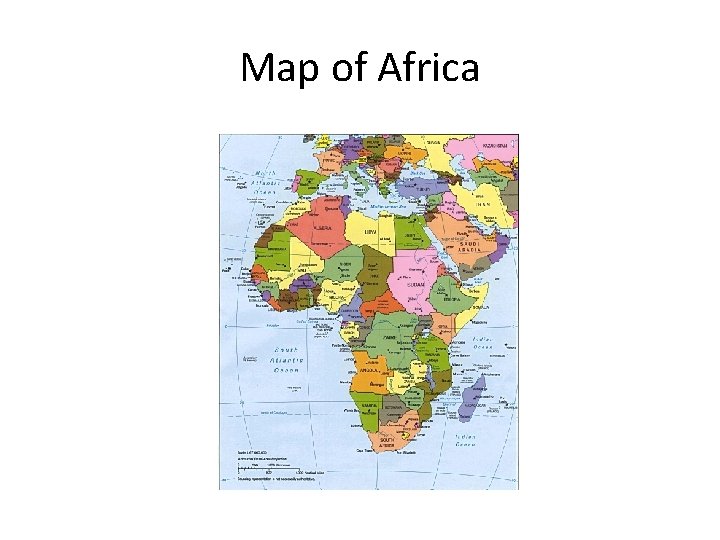

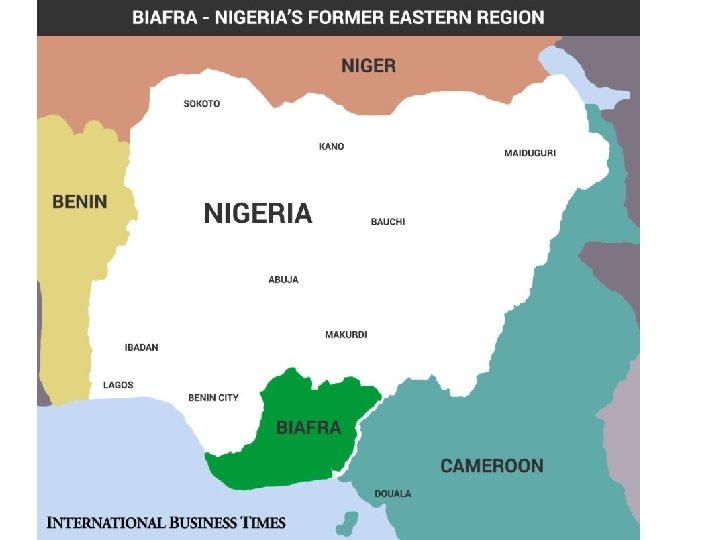

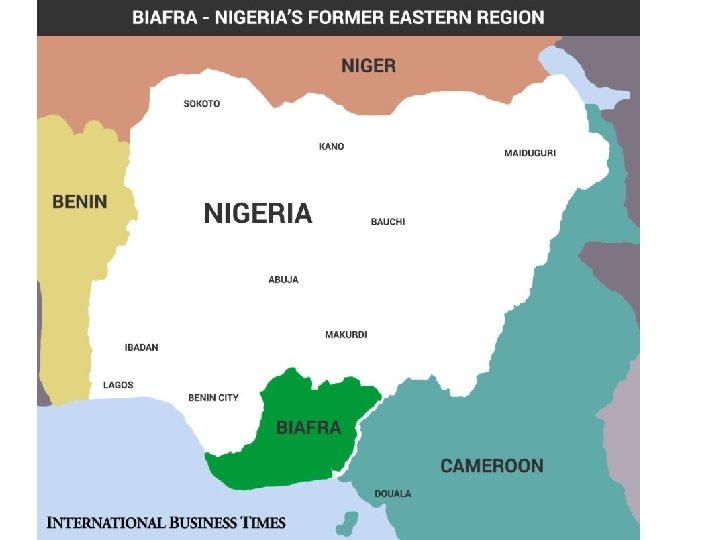

The Nigerian Civil War, also known as the Nigerian-Biafran War, was a three-year, bloody conflict with a death toll numbering more than one million people. The war began with the secession of the south-eastern region of the nation on May 30, 1967, when it declared itself the independent Republic of Biafra. The ensuing battles and well-publicized human suffering prompted international outrage and intervention. The boundaries of what became Nigeria were devised by British colonial planners, without regard for preexisting ethnic, cultural and linguistic divisions. Nigeria gained independence from Britain in 1960. Ethnic tension had run high during the colonial era, but the political instability reached a critical mass shortly after decolonisation among independent Nigeria’s three dominant ethnic groups: the Hausa-Fulani in the north, Yoruba in the southwest, and Igbo in the southeast. On January 15, 1966, the Igbo launched a coup d’état under the command of Major-General Aguiyi-Ironsi in an attempt to save the country from what Igbo leaders feared would be political disintegration. Shortly after this successful coup, widespread suspicion of Igbo domination was aroused in the north among the Hausa-Fulani Muslims, many of whom had opposed independence from Britain. Similar suspicions of the Igbo junta grew in the Yoruba west, prompting a joint Yoruba and Hausa-Fulani countercoup against the Igbo six months later. Countercoup leader General Gowon took punitive measures against the Igbo. Further anger over the murder of prominent Hausa politicians led to the massacre of scattered Igbo populations in northern Hausa-Fulani regions. This persecution triggered the move by Igbo separatists to form their own nation of Biafra the following year. Less than two months after Biafra declared its independence, diplomatic efforts to resolve the crisis fell apart. On July 6, 1967, the federal government in Lagos launched a full-scale invasion into Biafra. Expecting a quick victory, the Nigerian army buffeted Biafra with aerial and artillery bombardment that led to large scale losses among Biafran civilians. The Nigerian Navy also established a sea blockade that denied food, medical supplies and weapons, again impacting Biafran soldiers and civilians alike. Despite the lack of resources and international support, Biafra stood firm refusing to surrender in the face of overwhelming Nigerian military superiority. But the Nigerian Army continued to slowly take territory, and on January 15, 1970, Biafra surrendered when its military commander General Ojukwu fled to Cote d’Ivoire. During the civil war, an estimated 3, 000 to 5, 000 people died daily in Biafra from starvation.

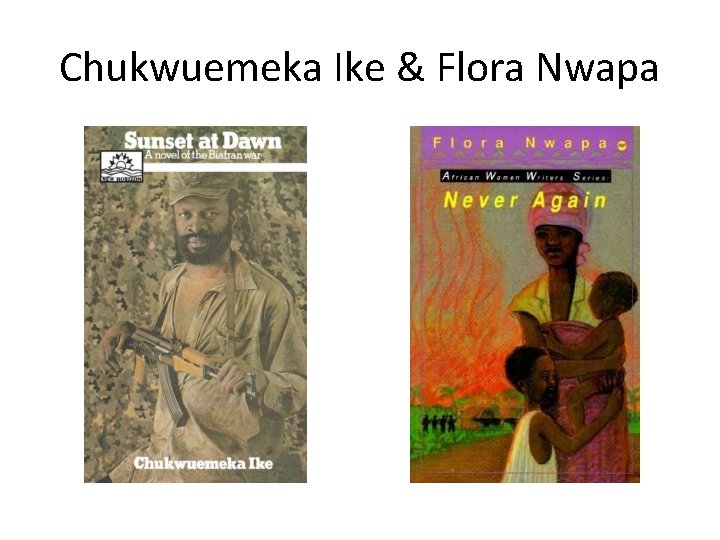

Chukwuemeka Ike & Flora Nwapa

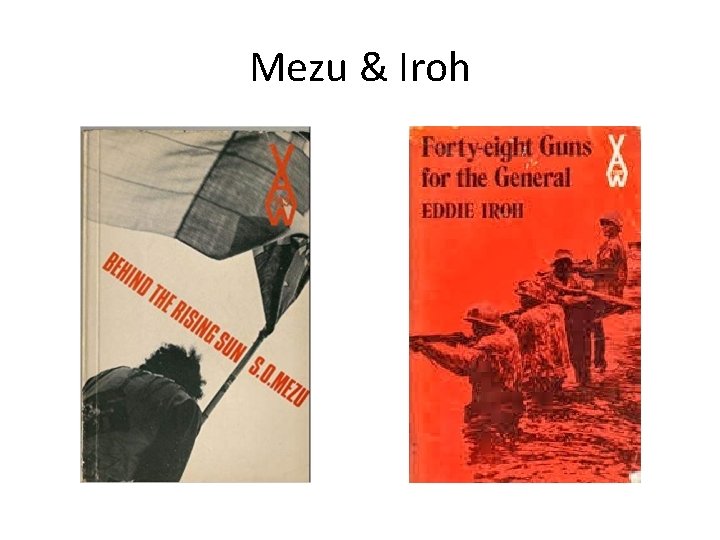

Mezu & Iroh

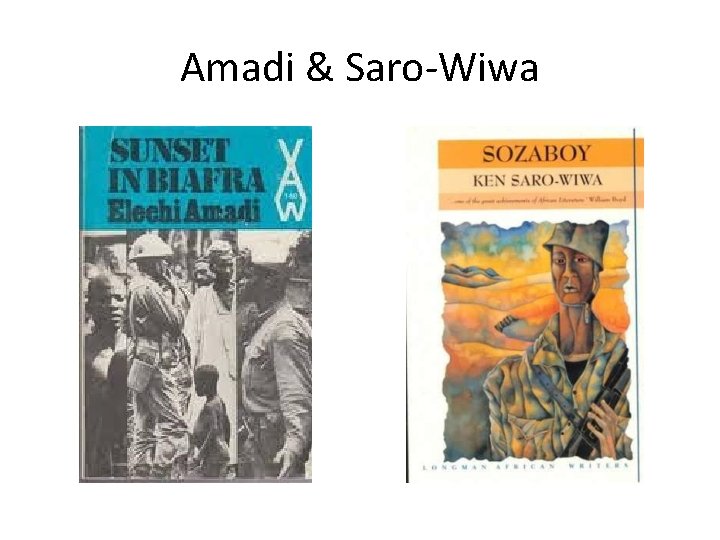

Amadi & Saro-Wiwa

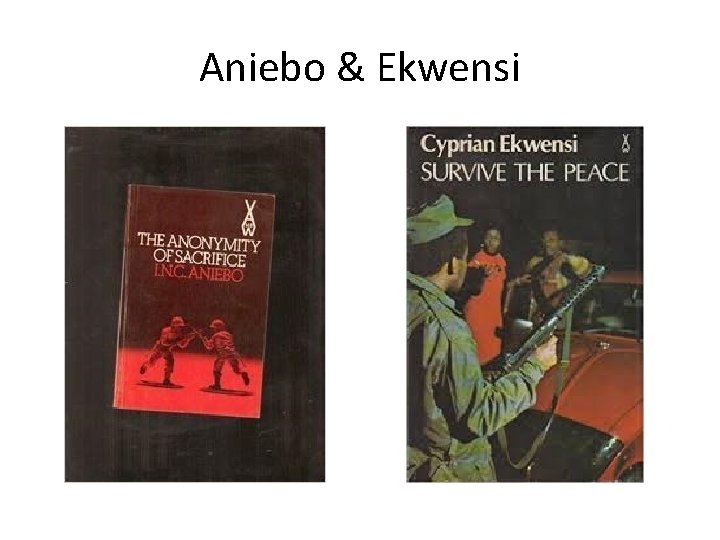

Aniebo & Ekwensi

Okpewho and Emecheta

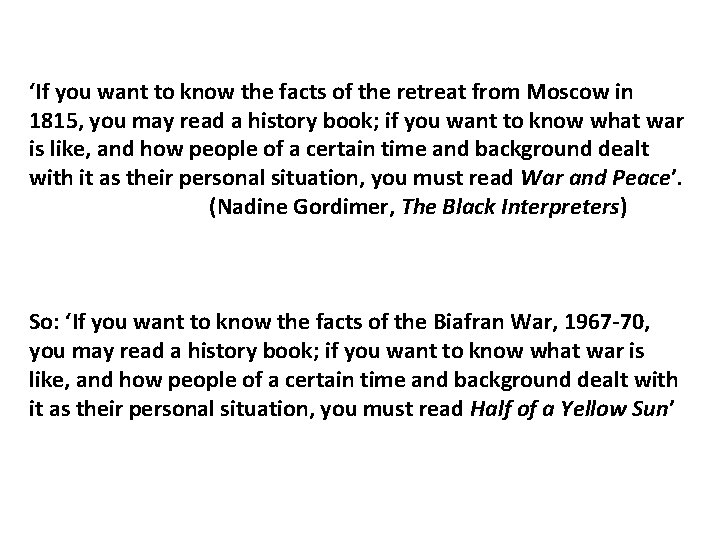

‘If you want to know the facts of the retreat from Moscow in 1815, you may read a history book; if you want to know what war is like, and how people of a certain time and background dealt with it as their personal situation, you must read War and Peace’. (Nadine Gordimer, The Black Interpreters) So: ‘If you want to know the facts of the Biafran War, 1967 -70, you may read a history book; if you want to know what war is like, and how people of a certain time and background dealt with it as their personal situation, you must read Half of a Yellow Sun’

‘Neither victors nor vanquished’ Olanna looking at the destroyed Nigerian fleet: ‘“They won but we did this, ” she said, and realized how odd it felt to say they won, to voice a defeat she did not believe. Hers was not a feeling of having been defeated: it was one of having been cheated…’

‘“Why do you still have Biafran number plates? Are you supporters of the defeated rebels? ” His voice was loud, contrived; it was as if he was acting and very aware of himself in the role of the bully. Behind him, one of his boys was shouting at the labouring men. A dead male body lay by the bush. “We will change it when we get to Nsukka, ” Odenigbo said. “Nsukka? ” The officer straightened up and laughed. “Ah, Nsukka University. You are the ones who planned the rebellion with Ojukwu, you book people. ” Odenigbo said nothing, looking straight ahead. The officer yanked his door open with a sudden movement. “Oya! Come out and carry some wood for us. Let’s see how you can help a united Nigeria. ”… When Odenigbo climbed out, the officer slapped his face, so violently, so unexpectedly, that Odenigbo fell against the car. Baby was crying. “You are not grateful that we didn’t kill all of you? Come on carry those wood planks quickly, two at a time!”’

![Arguably war has emerged problematically as the new authenticity out of Africa Arguably, war has emerged problematically as the new authenticity out of Africa […. ]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/e98cbf6fdcc663e386a4c6ed62d13278/image-26.jpg)

Arguably, war has emerged problematically as the new authenticity out of Africa […. ] because it addresses an international audience shaped by a humanitarian ethos that sees Africa through the lens of “distant suffering”. Although the seeds for this new writing can be found in key texts from the earlier period, the newer literature reflects the opening of a literary market for African writers in what critics have identified as “an emerging global subgenre” of human rights fiction […] at a time when publishing in Africa has declined, economic conditions for writers have become extremely difficult, and African universities are also in crisis. (Eleni Coundouriotis, The People’s Right to the Novel)

‘I don’t know how you write about Nigeria without dealing with sex’. (Adichie, ‘If you Don’t Want to Write About Sex’) ‘If touch and intimacy provide a vocabulary with which to remember and to describe such pain and violence, they also…provide a way into exploring the loss inherent in warfare. In addition to foregrounding the body and generating a language with which to explore pain, sexuality also functions in [the novel]… as a mnemonic – a physical experience that opens up pathways to the past, as a trigger for emotion and the recounting of history’. (Zoe Norridge, ‘Sex as Synecdoche’)

When we learn that Ugwu is the author of the “book within a book, ” we are caught in having made the wrong assumptions about historiographic authority. In the novel’s opening scene, Ugwu is an illiterate peasant boy, but, by the novel’s end, he has supplanted Richard as the designated historian […. ] The derivative nature of Ugwu’s book sits uncomfortably with the claim that the people’s history posits a distinct point of view. The sketch of Ugwu’s book provided in the novel glosses much of the existing historiography of the war, which Adichie, furthermore, cites in the bibliography at the end of the novel. In contrast, Adichie’s domestic fiction makes a different historiographic point, seeking to give a sympathetic account of the Igbo intellectual’s support for Biafra and their commitment to this nationalist dream. She wants to answer the question of how it is possible that they endorsed what turned out to be a catastrophic political agenda. (Eleni Coundouriotis, The People’s Right to the Novel)

Rex Lawson ‘So Ala Temen - Yellow Sisi - Love Mu Adure’ https: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=TFil. IFOl. Ze 8

American embassy chimamanda ngozi adichie

American embassy chimamanda ngozi adichie Imitation by chimamanda ngozi adichie

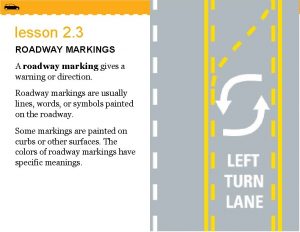

Imitation by chimamanda ngozi adichie Broken yellow center line

Broken yellow center line Red raised roadway marker

Red raised roadway marker Half empty or half full

Half empty or half full Half man half horse name

Half man half horse name Circumferential clasp indications

Circumferential clasp indications The joy luck club questions and answers

The joy luck club questions and answers What is a myth

What is a myth Top half vs bottom half

Top half vs bottom half Intracoronal direct retainer

Intracoronal direct retainer What is a half horse half man called

What is a half horse half man called Half mens half geit narnia

Half mens half geit narnia Hybrid mythological creatures

Hybrid mythological creatures Mulciber roman god

Mulciber roman god Half playful half serious

Half playful half serious Blue red blue yellow impossible quiz

Blue red blue yellow impossible quiz Caterpillar confidential green yellow red

Caterpillar confidential green yellow red Yellow dog contract

Yellow dog contract Spanish brute political cartoon

Spanish brute political cartoon Pokemon yellow hack

Pokemon yellow hack Huangdi dynasty

Huangdi dynasty ˈʃaʊə

ˈʃaʊə Agranulocytes

Agranulocytes Yellow tail wine blue ocean strategy

Yellow tail wine blue ocean strategy What happens in the yellow wallpaper

What happens in the yellow wallpaper Tire rotation pattern

Tire rotation pattern Wheres the tigris river

Wheres the tigris river The yellow wallpaper summary

The yellow wallpaper summary Jumpstart triage definition

Jumpstart triage definition