An Overview of Fiduciary Duties John D Wilson

- Slides: 28

An Overview of Fiduciary Duties John D. Wilson March 2016

Overview I. Fiduciary Duties — Generally II. Judicial Review Standards — Business Judgment Rule III. Judicial Review Standards — Enhanced Scrutiny § Unocal § Revlon/QVC § Recent cases on “Go Shop” provisions § Blasius IV. Judicial Review Standards — Entire Fairness V. Kahn v. M&F Worldwide Corp (Del. March 14, 2014) 2

Fiduciary Duties: Generally State corporation law — not federal securities law — governs the duties of directors. Delaware law requires that directors discharge their duties: § in good faith; § with the care that an ordinarily prudent person in a like position would use under similar circumstances; and § in a manner they reasonably believe to be in the best interests of the corporation and its stockholders. Directors owe two duties to the corporation and its stockholders: (i) Duty of Care, and (ii) Duty of Loyalty § Directors also have an obligation to act in good faith. Although it is sometimes colloquially termed a duty, it is really a component of the duty of loyalty. 3

Fiduciary Duties: Generally Duty of Care § Directors must take reasonable steps to become informed, prior to making a decision, of all information reasonably available to them (See Smith v. Van Gorkom, 488 A. 2 d 858 (Del. 1985)). § Directors must act on an informed basis and after careful consideration of all material facts and circumstances. § Directors’ decision-making process should reflect a thorough, careful and deliberate process in which the benefits and detriments of particular actions are discussed openly. § Gross negligence standard. 4

Fiduciary Duties: Generally Duty of Loyalty § Directors must act in a manner they reasonably believe to be in the best interests of the corporation and its stockholders (and not act out of self-interest). § Directors may not use their corporate position for personal gain or advantage. § The mere existence of a personal benefit (i. e. , a substantial golden parachute payment or promise of employment or promotion) which could give rise to allegations of a conflict of interest does not necessarily lead to a finding of breach of the duty of loyalty, if such conflict is properly disclosed to the Board and the Board insulates its decision-making process from the influence of such conflicted director. § If a director has any reason to suspect that he or she may have a conflict of interest, such director should bring it to the attention of the Board so that the Board can consider appropriate actions. 5

Fiduciary Duties: Generally Exculpation and Indemnification of Personal Liabilities of Directors § Delaware law provides that a corporation’s certificate of incorporation may eliminate or limit the personal liability of directors for monetary damages for breaches of the duty of care. § However, a director will be liable for monetary damages for, among other things a breach of the duty of loyalty, including acts or omissions not in good faith. § Delaware law also permits a corporation to indemnify a person who: § § … was or is a party or is threatened to be made a party to any action, suit or proceeding (other than an action by or in the right of the corporation) by reason of the fact that the person is or was a director, if the person acted in good faith and in a manner the person reasonably believed to be in, or not opposed to, the best interests of the corporation and, with respect to any criminal action or proceeding, had no reasonable cause to believe that the person’s conduct was unlawful. Consequently, a breach of the duty of loyalty (including acts or omissions not in good faith) will render exculpation and indemnification provisions unavailable to directors. 6

Fiduciary Duties: Generally Obligation to act in Good Faith § Directors must not consciously disregard their obligation to act and to exercise appropriate oversight of the corporation. § Directors with specialized knowledge not necessarily shared by other directors should apply that knowledge to their decision-making because they may be subject to a higher standard (See In re Emerging Communications Shareholder Litigation (Del. Ch. 2004)). § Directors will be found to have failed to act in good faith if they act with “subjective bad faith” (i. e. , motivated by an actual intent to do harm) or intentionally or consciously disregard their duties and responsibilities (See In re Walt Disney Company Derivative Litigation, 2005 Del. Ch. Lexis 113 (Del. Ch. 2005), aff’d, 2006 Del. Lexis 307 (Del. 2006)). § § Examples of “bad faith” include: (i) actions with a purpose other than advancing the best interests of the corporation; (ii) actions with the intent to violate applicable law or a disregard of the law; or (iii) intentional failure to act in the face of a known duty to act. Only violations of the duties of care and loyalty result in liability, but a failure to act in good faith may support a finding of a breach of the duty of loyalty (See William Stone and Sandra Stone v. Ritter, 911 A. 2 d 362 7 (Del. 2006)).

Fiduciary Duties: Generally Delaware law expressly authorizes a director to rely in good faith on corporate records and information, opinions, reports or statements, including any financial statements or other financial data, prepared or presented by: § officers or employees of the corporation whom the director reasonably believes to be reliable and competent in the matters presented; § a lawyer, financial advisor, certified public accountant or other expert, as to a matter which the director reasonably believes to be within such person’s professional or expert competence and who has been selected with reasonable care by the corporation; or § a board committee on which the director does not serve, as to a matter within its designated authority, if the director reasonably believes the committee merits confidence. 8

Judicial Review Standards: Business Judgment Rule § The Business Judgment Rule is an evidentiary presumption applied by Delaware courts that in making a business decision the directors acted: § on an informed basis, § in good faith, and § in the honest belief that the action taken was in the best interests of the corporation and its stockholders. § Decisions made by the Board are generally protected by the Business Judgment Rule under Delaware law. § A stockholder can rebut this presumption by showing by a preponderance of the evidence that the Board of Directors has failed to satisfy one of its fiduciary duties. § If the presumption is not rebutted, courts will not inquire further into the challenged Board decision. § If the presumption is rebutted, the burden of proof shifts to the Board of Directors to prove the entire fairness of the challenged decision to 9 both the corporation and its stockholders.

Judicial Review Standards: Unocal Enhanced Judicial Scrutiny Applied to Adoption of Defensive Measures § In situations involving preemptive, precautionary or defensive measures taken by a board to defend against alleged threats to corporate control or policy, courts apply enhanced judicial scrutiny (i. e. , the Unocal test). § Note these apply even when the directors are not otherwise “conflicted” (are not part of the buy-side); is a hybrid challenge because courts are concerned that directors may naturally favor “incumbent” management vs. external bidders § Earlier cases (Cheff v. Mathes (1964) focused on whether Board acted “solely or primarily” to perpetuate themselves in office; test became too narrow § Under Unocal, the initial burden lies with the directors, who must prove their conduct satisfies a two-prong test: § Reasonableness Test — the board, in good faith and after a reasonable investigation, had reasonable basis to believe that a danger to corporate policy and effectiveness existed; and § Proportionality Test —the defensive response was reasonable compared 10

Judicial Review Standards: Unocal Analysis (cont’d) § The Delaware Supreme Court has given directors wide latitude in determining whether a threat exists. Examples of potential threats to corporate policy include: § Coercive offers; or takeover threats by a known “bust up” acquirer using considerable debt that might undermine the company’s long-term strategic progress § Price inadequacy of an offer in light of the corporation’s long-term strategic plans § Insufficient time or information to assess price adequacy of an offer; even in the face of an all-cash, non-coercive offer § Change in corporate culture if existing culture is distinctive and advantageous § Delaware’s approach is consistent with Board-centric philosophy that “trusts” an independent Board, acting after a reasonable investigation, to act in the interests of the company and its shareholders 11

Judicial Review Standards: Unocal Facts of Unocal § Mesa Petroleum acquired 13% of Unocal’s shares in the market and launched a hostile bid in the form of a “front-end loaded” cash tender offer for another 37% of Unocal’s shares at $54 per share with an announced intention of a second-step merger in which the remaining stockholders would receive subordinated junk bonds with a $54 face amount. § In response to Mesa Petroleum’s plans, after two board meetings, Unocal decided to make an exchange offer for 49. 9% of its own shares in exchange for Unocal senior secured debt valuing such shares at $72 per share. The exchange offer specifically excluded the hostile bidder, Mesa Petroleum. Outcome of Unocal § The Delaware Supreme Court held that: § Unocal’s board had reasonable grounds to believe that Mesa Petroleum’s proposed transaction threatened Unocal and its stockholders; and § the defensive measure adopted by Unocal’s board was reasonable in relation to that threat. 12

Judicial Review Standards: Revlon/QVC Enhanced Judicial Scrutiny Applied to Sale of Control or Breakup of a Corporation § Revlon and QVC Doctrines § § § Directors are obligated to seek the best present value reasonably available to stockholders if a corporation undertakes a transaction that will cause: § a change in corporate control; or § a breakup of the corporate entity. In such contexts, directors have the burden of proving that they were adequately informed and acted reasonably. Examples of When Revlon/QVC Duties Are Triggered § A corporation initiates an active bidding process to sell itself or which involves a reorganization resulting in a clear break-up of the company. § In response to a bidder’s offer, a target abandons its long-term strategy and seeks an alternative transaction involving the break-up of the company. § Transaction will result in a change of control of the company. 13

Judicial Review Standards: Revlon/QVC Doctrines (cont’d) Generally, courts require that the “playing field” for bidders be as level as possible. Any defensive actions or deal protections should serve to encourage bids for the benefit of stockholders, not restrict the number of bidders. § The use and scope of break-up fees, cross-options and no-shops, etc. , must be measured and ultimately must provide benefits to stockholders. § Note: Revlon and QVC do not require an auction, and a limited break-up fee may be granted to a bidder, provided it is not preclusive. § Note: Revlon/QVC duties do not arise in a stock-for-stock merger between two widely held public companies, where the combined entity is not controlled by an individual or a “cohesive group” after the merger. § § However, in a recent decision, the Delaware Chancery Court criticized the defendants’ argument that a proposed merger is a “merger of equals” and therefore did not constitute a change of control triggering 14 the Revlon duties. This suggests that the Delaware courts will scrutinize

Judicial Review Standards: Revlon Facts of Revlon § Pantry Pride (Ron Perelman), after private attempts to acquire Revlon, made a hostile tender offer for Revlon at $45 per share. Revlon’s board deemed the offer inadequate and adopted a poison pill and a share repurchase plan. § When Pantry Pride commenced the tender offer, the offer price was increased to $47. 50 per share. Revlon’s board advised stockholders to reject the offer and commenced the share repurchase plan. Pantry Pride then raised its bid to $53 per share. § In the meantime, Revlon hunted for a “White Knight” and agreed to an LBO of the company by Forstmann Little at $56 per share. § Pantry Pride then raised its offer to $56. 25 per share – then Forstmann raised its own offer to $57. 25 per share with a number of conditions such as a “no-shop” provision, the removal of the poison pill and a lock-up option to purchase Revlon’s Vision Care and National Health Laboratories divisions for approximately $100175 million less than the market value if another acquiror were to obtain 40% of Revlon’s shares. Revlon accepted Forstmann’s offer. 15

Judicial Review Standards: Revlon Outcome of Revlon § Given that the change of control of Revlon had become inevitable, the Court found that Revlon’s directors breached their duty of loyalty to the stockholders by acceding to the lock-up option and other conditions to Forstmann’s bid and effectively ending the bidding for the company. § Revlon’s board’s authorization of management to negotiate a merger or buyout with a third party was a recognition that the company was for sale. 16

Judicial Review Standards: Revlon § Often a public auction or a so-called “market check, ” but neither is required. § A public company conducting an auction may reverse an earlier decision to sell the company and pursue an alternative long-term strategy (incl. a merger not involving a change of control), without violating any Revlon duties. See Arnold v. Society for Saving Bancorp. , Inc. , 650 A. 2 d 1270 (Del. 1994). § There is “no single blue-print” that a board must follow to fulfill its duties. See Barkan v. Amsted Industries, 567 A. 2 d 1279, 1286 (Del. 1989). § However, certain fact patterns suggest particular responses: § With multiple bidders, the scrupulous concern for fairness to stockholders forbids directors from using defensive mechanisms to thwart or to favor one bidder § When the board is considering a single offer and has no reliable grounds upon which to judge its adequacy, the concern for fairness demands a canvas of the market to determine if higher bids may be 17 elicited

Judicial Review Standards: Revlon/QVC Application of Revlon — Paramount v. QVC § Facts of QVC § Paramount’s directors approved a merger agreement with Viacom pursuant to which, upon consummation of the merger, the combined company would have been controlled by Sumner Redstone. § The merger agreement contained three principal deal protections: § § § a no-shop provision; a $100 million termination fee; and a 19. 9% stock option for Viacom if the merger agreement was terminated. QVC told Paramount it was prepared to buy Paramount and brought suit to challenge the Paramount/Viacom deal. Outcome of QVC § The Court held that the Paramount directors breached their Revlon duties by failing to take actions that would be reasonably believed to maximize stockholder value. § The duty to seek the reasonably best value arose because after the merger, one individual would have ended up with a controlling block of Paramount’s stock. 18

Judicial Review Standards: Revlon/Go Shop In re: Netsmart Technologies, Inc. Shareholders Litigation § 2007 WL 926213 (Del. Ch. March 14, 2007) Facts: § Following a limited auction process composed solely of private equity buyers, Netsmart Technologies (“Netsmart”), a micro-cap company, entered into a merger agreement with two private equity buyers for $16. 50 in cash per share. The merger agreement contained a “window -shop” provision. § Netsmart shareholders filed suit to enjoin the consummation of the merger. Outcome: § The Court held that the plaintiffs established a reasonable probability of success on showing that the Board had breached its Revlon duties by failing to seek out any strategic buyers in the sale process. § The Court also found that deal protection measures employed by a micro-cap target, including a customary “window-shop” provision, were more viable for large-cap deals than micro-cap deals. The Board should have made serious sales efforts to pitch to strategic buyers, rather than relying on “an inert, implicit post-signing market check. ” 19

Judicial Review Standards: Revlon/Go Shop In re: The Topps Company Shareholders Litigation § 2007 WL 1732586 (Del. Ch. June 14, 2007) Facts: § In March 2007, the Topps Company, Inc. (“Topps”) entered into a merger agreement with a company controlled by Michael Eisner pursuant to which Topps shareholders would be cashed out at $9. 75 per share. § The Upper Deck Company (“Upper Deck”) had made a proposal to acquire Topps for $10. 75 per share. Upper Deck and a group of Topps shareholders filed a motion for a preliminary injunction. Outcome: § The Court noted that even though the target had not conducted an auction prior to entering into a merger agreement, the fact that the target had recently held a failed auction and been through a significant proxy contest was enough to give notice to all potential buyers. The Court also noted that the 40 -day “Go-Shop” period provided in the merger agreement allowed the target’s board to “shop like Paris Hilton” and afforded “reasonable room for an effective post-signing market check. ” § However, the Court also held that certain disclosure failures and Topps’ refusal to release Upper Deck from its Standstill Agreement was a violation of fiduciary duties. 20

Query: in applying Revlon/QVC § Under what circumstances can a board forego an auction? § Can a board ever justify accepting a deal at a lower price? § Can Revlon ever apply to a stock for stock deal? 21

Judicial Review Standards: Blasius Enhanced Judicial Scrutiny Applied to Actions that Thwart a Stockholder Vote § The Blasius Standard § Regardless of the good faith of the directors, any director action taken for the primary purpose of frustrating the exercise of the stockholder franchise will only be permitted if the directors can show a compelling justification for such action. 22

Judicial Review Standards: Blasius Facts of Blasius § Atlas Corporation was confronted with a hostile takeover attempt by Blasius Industries, an investment vehicle formed by venture capitalists and financed by Drexel Burnham. § Blasius acquired approximately 9% of Atlas’ stock and proposed to recapitalize Atlas with a heavy debt load and apply the proceeds to pay a large special dividend to stockholders, payable in cash and notes. § Atlas’ board, advised by independent investment bankers and acting without any conflict of interest, concluded that the plan was impractical, risky and not in the best interests of stockholders. § Blasius attempted to take control of Atlas through a consent solicitation proposing the following: § § Adoption of a resolution recommending that the board implement Blasius’ restructuring proposal; and § Amending the bylaws of Atlas to expand the board from 7 to 15 members and electing 8 nominees selected by Blasius. Atlas’ board responded to the consent solicitation by increasing the size of the board by 2 and nominating 2 new directors to fill the created vacancies. § The practical effect would be to make it impossible for Blasius to gain control of Atlas’ board (which was limited by charter to 15 directors). 23

Judicial Review Standards: Blasius Outcome of Blasius § The Court found that the board was expanded for the primary purpose of frustrating the exercise of stockholder voting rights. § The Court held that regardless of the good faith of directors, director action taken for the primary purpose of frustrating an exercise of the stockholder franchise will only be permitted if the directors can show a “compelling justification for the action. ” (emphasis added) § The Court concluded that the board’s goal of preventing Blasius from securing board control and implementing its proposed restructuring did not present such a justification. The expansion of Atlas’ board was enjoined. 24

Judicial Review Standards: Blasius Hypothetical § Internet Networks Company, Inc. (“INC”) and Mobile Appliances (“MA”) enter into an all-cash merger agreement, whereby MA will acquire INC. Deal is subject to a stockholder vote. § Sam Minor, INC founder, former CEO and minority stockholder, opposes the deal and launches a proxy contest soliciting stockholder votes against the merger. § On the morning of the special meeting, fairly certain the merger will not be approved, the Board postpones the vote for 30 days and resets the record date used to determine which stockholders would be able to vote at the meeting. § Questions for consideration: Did the board have a compelling justification for postponing the vote? § How might the board try to justify postponing the vote in light of its fiduciary duties? § What if the board cited one of the following reasons for delaying the vote: § § § turmoil in the credit markets? pending announcement of quarterly financial results of INC? 25

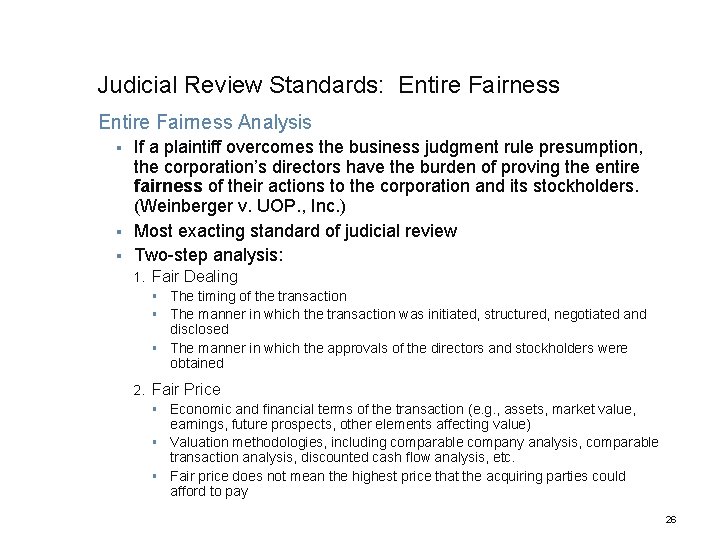

Judicial Review Standards: Entire Fairness Analysis If a plaintiff overcomes the business judgment rule presumption, the corporation’s directors have the burden of proving the entire fairness of their actions to the corporation and its stockholders. (Weinberger v. UOP. , Inc. ) § Most exacting standard of judicial review § Two-step analysis: § 1. Fair Dealing The timing of the transaction § The manner in which the transaction was initiated, structured, negotiated and disclosed § The manner in which the approvals of the directors and stockholders were obtained § 2. Fair Price Economic and financial terms of the transaction (e. g. , assets, market value, earnings, future prospects, other elements affecting value) § Valuation methodologies, including comparable company analysis, comparable transaction analysis, discounted cash flow analysis, etc. § Fair price does not mean the highest price that the acquiring parties could afford to pay § 26

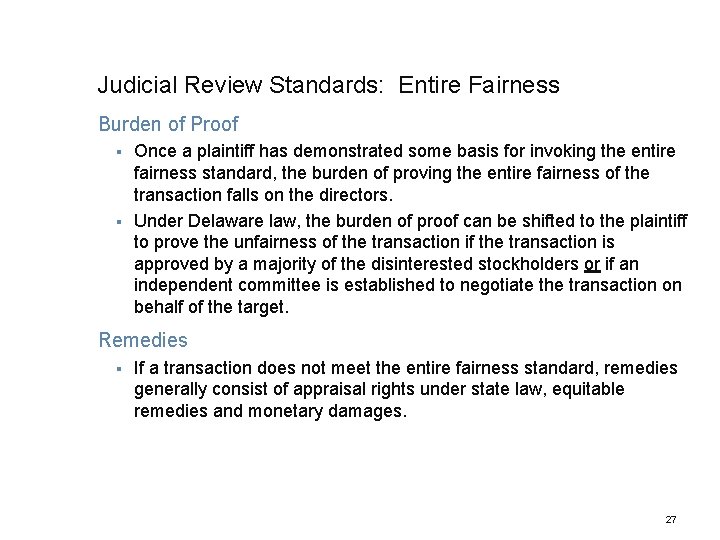

Judicial Review Standards: Entire Fairness Burden of Proof Once a plaintiff has demonstrated some basis for invoking the entire fairness standard, the burden of proving the entire fairness of the transaction falls on the directors. § Under Delaware law, the burden of proof can be shifted to the plaintiff to prove the unfairness of the transaction is approved by a majority of the disinterested stockholders or if an independent committee is established to negotiate the transaction on behalf of the target. § Remedies § If a transaction does not meet the entire fairness standard, remedies generally consist of appraisal rights under state law, equitable remedies and monetary damages. 27

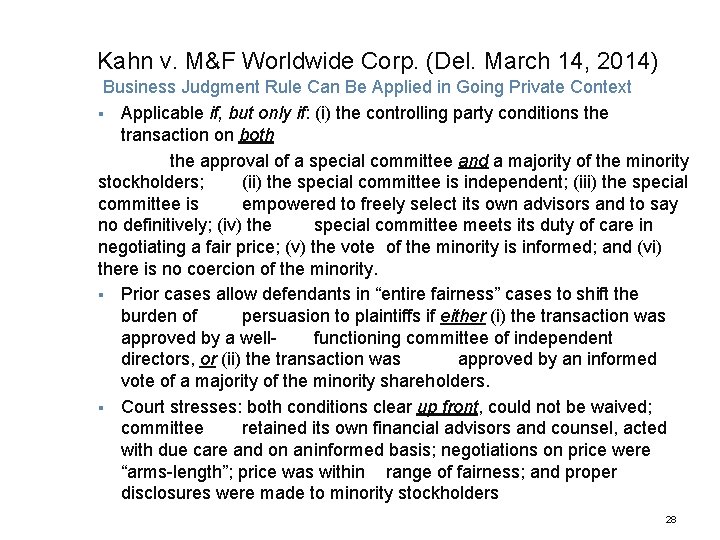

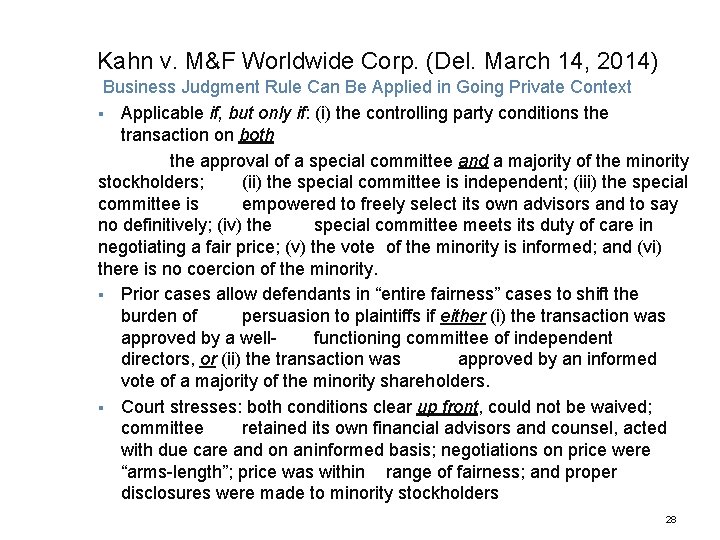

Kahn v. M&F Worldwide Corp. (Del. March 14, 2014) Business Judgment Rule Can Be Applied in Going Private Context § Applicable if, but only if: (i) the controlling party conditions the transaction on both the approval of a special committee and a majority of the minority stockholders; (ii) the special committee is independent; (iii) the special committee is empowered to freely select its own advisors and to say no definitively; (iv) the special committee meets its duty of care in negotiating a fair price; (v) the vote of the minority is informed; and (vi) there is no coercion of the minority. § Prior cases allow defendants in “entire fairness” cases to shift the burden of persuasion to plaintiffs if either (i) the transaction was approved by a wellfunctioning committee of independent directors, or (ii) the transaction was approved by an informed vote of a majority of the minority shareholders. § Court stresses: both conditions clear up front, could not be waived; committee retained its own financial advisors and counsel, acted with due care and on aninformed basis; negotiations on price were “arms-length”; price was within range of fairness; and proper disclosures were made to minority stockholders 28

Remedies for breach of fiduciary duties

Remedies for breach of fiduciary duties Sgt john wilson summary

Sgt john wilson summary Responsibilities

Responsibilities Va fiduciary hub louisville ky

Va fiduciary hub louisville ky Fidelity personal trust services

Fidelity personal trust services Fiduciary risk assessment

Fiduciary risk assessment Va fiduciary field examination

Va fiduciary field examination Fox rothschild fiduciary attorney summit

Fox rothschild fiduciary attorney summit Fiduciary risk assessment

Fiduciary risk assessment Accounting for fiduciary funds

Accounting for fiduciary funds Key risk indicators template

Key risk indicators template Fiduciary investment risk management association

Fiduciary investment risk management association Duties of personal ministries leader

Duties of personal ministries leader Substitute decision maker vs power of attorney

Substitute decision maker vs power of attorney Wd ross theory

Wd ross theory What does moral reasoning mean

What does moral reasoning mean Life roles examples

Life roles examples Duties and responsibilities of boy scout coordinator

Duties and responsibilities of boy scout coordinator Lions club treasurer duties

Lions club treasurer duties Treasure role

Treasure role Non legislative duties of congress

Non legislative duties of congress 5 daily duties of hinduism

5 daily duties of hinduism Regulate public conduct and set out duties owed to society.

Regulate public conduct and set out duties owed to society. Scrub nurse responsibilities

Scrub nurse responsibilities Sector officer

Sector officer Paraprofessional duties checklist

Paraprofessional duties checklist Moral duties

Moral duties Pmo duties and responsibilities

Pmo duties and responsibilities Duty vs responsibility

Duty vs responsibility