An Introduction to Primate Morphology PONGIDS V HOMINIDS

- Slides: 23

An Introduction to Primate Morphology PONGIDS V. HOMINIDS

THE FOOT � Hominids (humans) possess an arch from heel to toe; all toes aligned; the human foot is specialized for bipedal walking, running, and standing � Pongids (apes) have no arch; their big toe is opposable, which can be used to touch and grasp objects

ARMS AND HANDS � Pongids depend on their arms for either climbing or semi-erect walking; gorillas walk on their knuckles; their arms are still influenced by a lifestyle of brachiating (climbing) � Hominid arms and hands are free to carry, throw, and pick up objects without impeding their ability to walk or run; our thumbs are larger and more muscular (in ratio) which gives us a more precise, powerful, yet delicate grip—a hallmark of humanity

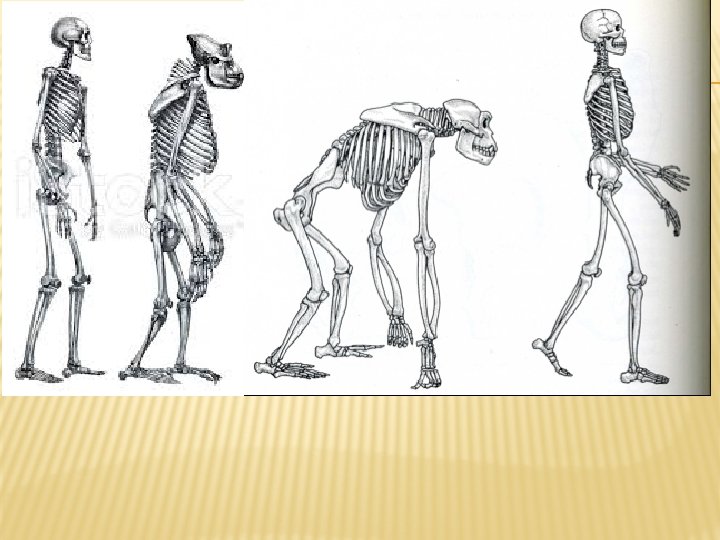

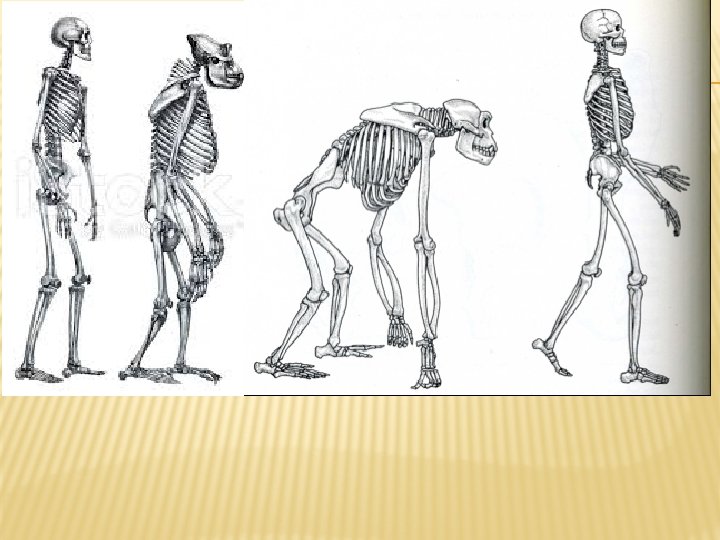

THE LOWER LIMBS The major difference between pongids and hominids is the relative length of the legs compared with “trunk length” (body); humans possess much longer legs � Hominids also possess prominently curvaceous calf muscles which are considerably more developed than apes � The gluteal muscles of humans are also dramatically massive in comparison, providing the necessary force for walking uphill, jumping, running, and straightening up after bending (things we take for granted) �

THE PELVIS � Pongids, like most quadrupeds, have a long tubular pelvis to which the rear legs attach at a 90 -degree angle; about ½ of the animal’s weight is transmitted through the pelvis to the rear legs where the brunt of its total body weight is endured � Hominids have a “basin-like” pelvis where the center of gravity passes directly through it, helping to hold the body erect; the hip bones are broader providing the power to move the leg muscles in bipedal movement

THE VERTEBRAL COLUMN � The vertebral column for apes is curved, and possesses long, spiny rearward extensions that anchor the large neck muscles � The hominid spine developed extra vertebrae, which forms a unique “lumbar curve; ” the curve towards the center of the pelvis creates a “sickle” shape, which keeps us from toppling backwards

THE NECK � For apes, the main weight of the skull is well forward of the pivot points, and the spinal column enters at the back of the skull, which needs heavy, powerful neck muscles to keep stability (see the vertebrae) � Human necks are relatively small and thin, requiring muscles to keep the head balanced atop the spinal column, which enters towards the center of the skull

THE PONGID CRANIUM � The rear portion of the skull to which the neck muscles are attached is called the nuchal plane � In pongids this area is very large and rises to form an abrupt angle known as the nuchal crest � Pongids have a prominent boney ridge known as the sagittal crest which is used to primarily for the attachment of massive jaw muscles to the skull

THE HUMAN CRANIUM Homo sapiens lack a nuchal crest, and the nuchal plane is smaller, found underneath rather than at the rear of the skull � The human cranium is smooth and spherical in comparison, and continues to rise into a forehead region, implying the largest and heaviest brain-body ratio � The maximum width of the skull is above the ears, not below as with apes � Though early species of homo had varying degrees of prominent crests, they are absent in modern humans �

THE FACE AND UPPER JAW (PONGIDS) � The pongid face extends beyond the plane of the forehead, with their jaws thrusting outwards known as prognathism � The supraorbital torus over the eyes is significantly pronounced, creating a ridge that supports the upper face against the massive jaws and chewing muscles

THE FACE AND UPPER JAW (HOMINIDS) � The human face is orthognathic, meaning it is vertically aligned with the forehead � In contrast to apes, humans have much smaller jaws, less powerful chewing muscles, and a smaller supraorbital torus � The human forehead, as explained earlier, is plainly pronounced

THE LOWER JAW AND TEETH (PONGIDS) � The pongid jaw features a “u-shaped” dentition, where the premolars and molars are aligned in parallel rows, with the incisors and canines forming a distinct arc � The incisors and canines are larger than their molars, jutting out (mainly used for cutting and ripping woody shoots and tough skins of forest vegetation) � Pongid canines are so large that a gap exists between the canine and second incisor (a diastema) to allow for the mouth to close

THE LOWER JAW AND TEETH (HOMINIDS) � Pongids and hominids share the same dentition ratio: 2: 1: 2: 3 (Incisors: Canines: Premolars: Molars) � The human jaw is much less pronounced and the teeth are arranged in a parabolic pattern, greatly compressed to fit the orthognathic nature of the face � The incisors and canines are much smaller than the molars, indicating the human feeding pattern of chewing � Humans also possess a chin

Do monkeys have 4 hands

Do monkeys have 4 hands Hominids

Hominids Hominids

Hominids 8 inflectional morphemes

8 inflectional morphemes Introduction to morphology and syntax

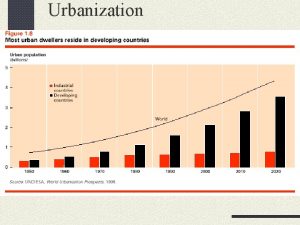

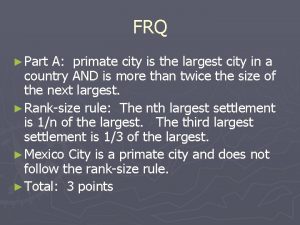

Introduction to morphology and syntax Primate cities

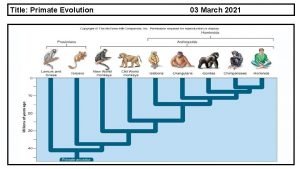

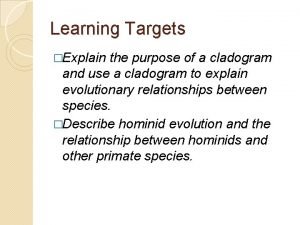

Primate cities Primate evolution tree

Primate evolution tree Rank size formula

Rank size formula Primate city and rank size rule

Primate city and rank size rule Is barcelona a primate city

Is barcelona a primate city Primate traits

Primate traits Primate cities

Primate cities 2 positive effects of primate cities

2 positive effects of primate cities Primate suite of traits

Primate suite of traits Chapter 16 primate evolution study guide answer key

Chapter 16 primate evolution study guide answer key Law of primate city

Law of primate city Primate taxonomy

Primate taxonomy Infraversion dental definition

Infraversion dental definition Cladogram purpose

Cladogram purpose Incisal labiality

Incisal labiality Chapter 16 primate evolution

Chapter 16 primate evolution Mesial step vs distal step

Mesial step vs distal step Borchert's epochs ap human geography definition

Borchert's epochs ap human geography definition Primate husbandry

Primate husbandry