ZOOM Paradise Lost The Duchess of Malfi Monday

- Slides: 30

ZOOM ‘Paradise Lost’ & ‘The Duchess of Malfi’ Monday 18 th January 2021

Learning Purposes • Exam specifications • Exploring theme of ‘ambition and its dangers’ • Recap – Eve and the Duchess in relation to theme • Contextual issues. • Explore the character of Satan in relation to theme. Previous Learning: You have read ‘Paradise Lost’ and ‘The Duchess of Malfi’. You will be reading these texts again in your ‘enrichment’ lesson Future Learning: Internal assessment in accordance with examination board specifications.

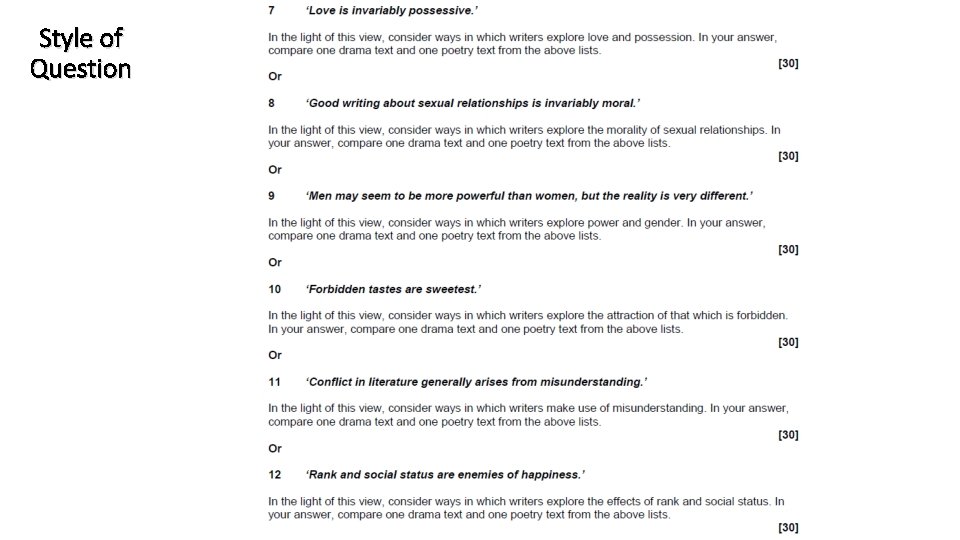

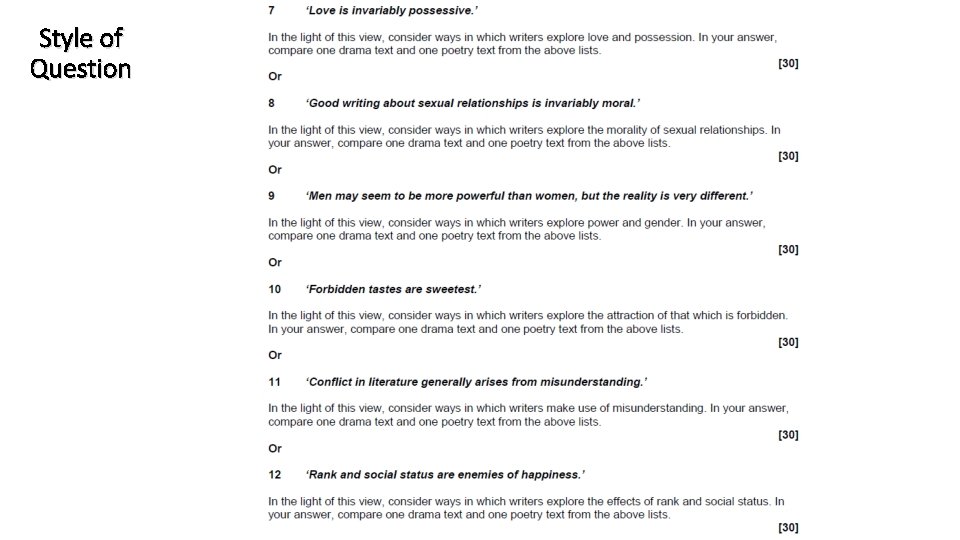

Style of Question

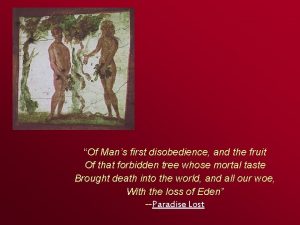

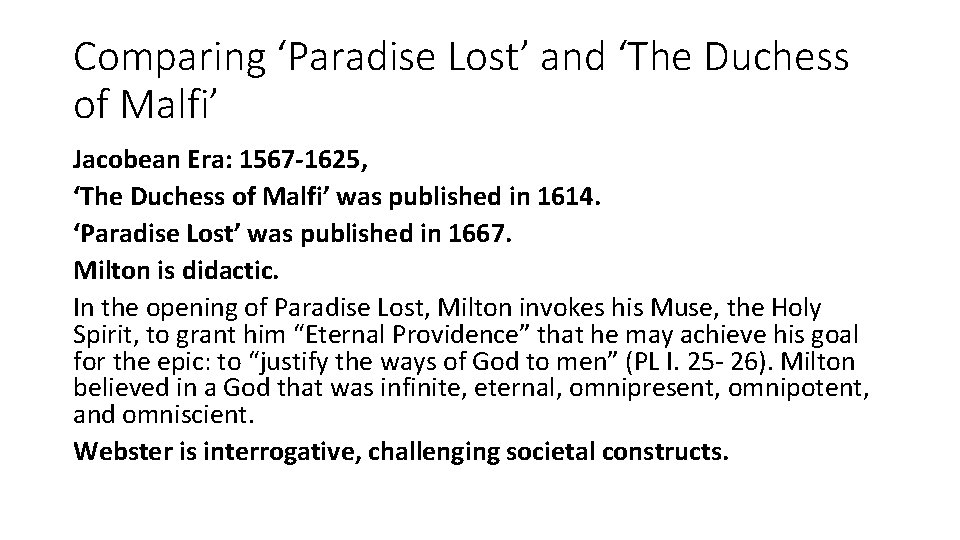

Comparing ‘Paradise Lost’ and ‘The Duchess of Malfi’ Jacobean Era: 1567 -1625, ‘The Duchess of Malfi’ was published in 1614. ‘Paradise Lost’ was published in 1667. Milton is didactic. In the opening of Paradise Lost, Milton invokes his Muse, the Holy Spirit, to grant him “Eternal Providence” that he may achieve his goal for the epic: to “justify the ways of God to men” (PL I. 25 - 26). Milton believed in a God that was infinite, eternal, omnipresent, omnipotent, and omniscient. Webster is interrogative, challenging societal constructs.

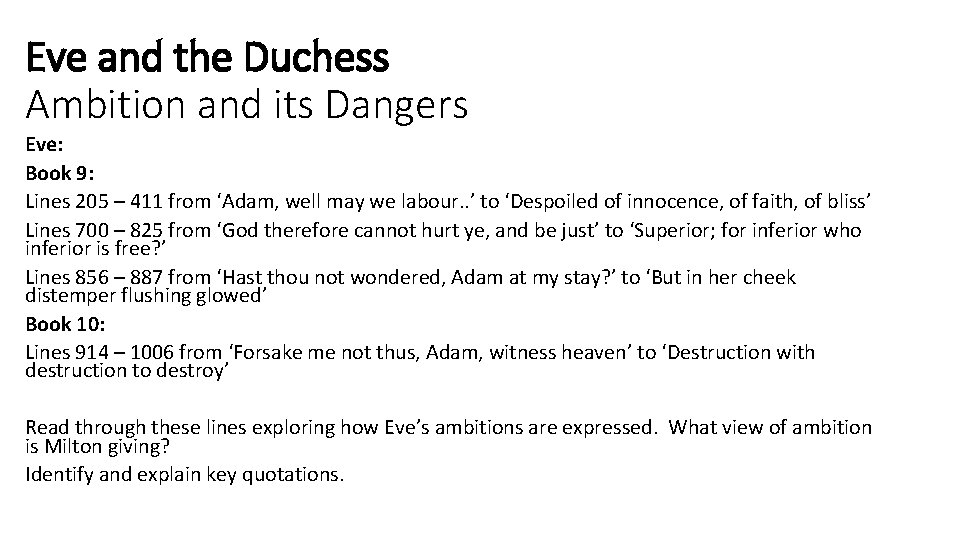

Eve and the Duchess Ambition and its Dangers Eve: Book 9: Lines 205 – 411 from ‘Adam, well may we labour. . ’ to ‘Despoiled of innocence, of faith, of bliss’ Lines 700 – 825 from ‘God therefore cannot hurt ye, and be just’ to ‘Superior; for inferior who inferior is free? ’ Lines 856 – 887 from ‘Hast thou not wondered, Adam at my stay? ’ to ‘But in her cheek distemper flushing glowed’ Book 10: Lines 914 – 1006 from ‘Forsake me not thus, Adam, witness heaven’ to ‘Destruction with destruction to destroy’ Read through these lines exploring how Eve’s ambitions are expressed. What view of ambition is Milton giving? Identify and explain key quotations.

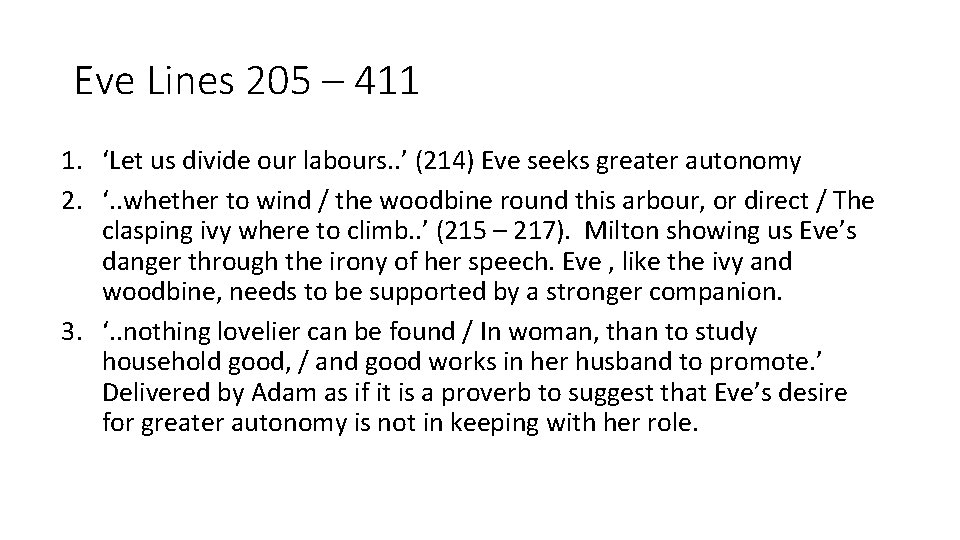

Eve Lines 205 – 411 1. ‘Let us divide our labours. . ’ (214) Eve seeks greater autonomy 2. ‘. . whether to wind / the woodbine round this arbour, or direct / The clasping ivy where to climb. . ’ (215 – 217). Milton showing us Eve’s danger through the irony of her speech. Eve , like the ivy and woodbine, needs to be supported by a stronger companion. 3. ‘. . nothing lovelier can be found / In woman, than to study household good, / and good works in her husband to promote. ’ Delivered by Adam as if it is a proverb to suggest that Eve’s desire for greater autonomy is not in keeping with her role.

Eve Lines 205 – 411 • When Adam reminds Eve that, if separated, she could be vulnerable to the ‘malicious foe’, Eve becomes agitated, suggesting that she insulted by Adam’s lack or faith in her: ‘His fraud is then thy fear, which plain infers / thy equal fear that my firm faith and love / Can by his fraud be shaken or seduced. ’ The heavy use of alliteration emphasises Eve’s agitation. Here she argues that Adam’s doubts are unfounded and that she is more capable of autonomy than he thinks. • ‘If this be our condition, thus to dwell / In a narrow circuit straightened by a foe’ Eve argues that they cannot be happy living in such confinement. She goes on to say ‘And Eden were no Eden thus exposed. ’

Eve Lines 205 – 411 • Milton shows us that Eve’s ambitious desire for greater autonomy is doomed: ‘O much deceived, much failing, hapless Eve, / Of thy presumed return! Event perverse!’ (404 – 405) (event = outcome; perverse = gone astray)

Eve Lines 700 – 825 • In this section we see how Satan exploits Eve’s ambition for greater autonomy by flattering her. Her ambition makes her easily seduced by his deception. • ‘. . ye shall be as gods, / Knowing both good and evil as they know. ’(708 – 709) Satan here implies that Eve can be raised on a level with God. He suggests that she and Adam are kept confined and ignorant by God so they are in awe of him. • Milton shows how vulnerable Eve is to such flattery: ‘…his words replete with guile / Into her heart too easy entrance won. ’ (733 – 734)

Eve Lines 700 – 825 • ‘Forbids us good, forbids us to be wise? / Such prohibitions bind not. ’ (759 – 760) Eve refuses to live under such restrictions. Her ambition leads her to reject the conditions laid down by God. Her use of language (‘forbid’, ‘prohibition’) presents a very negative view of God who is seen as an oppressive figure who stifles freedom and autonomy. On Line 815 she refers to God as, ‘Our great forbidder’ • Eve’s ambition leads her to transgress with great excess ‘Greedily she engorged without restraint. ’ (791) • Eve’s desire to be equal to Adam quickly passes to the idea of being superior ‘But keep the odds of knowledge in my power / Without copartner? ’ (821 – 822)

Eve Lines 856 – 887 • Eve, now aware that she may die, is frightened of her possible separation from Adam. Her ambitious desire for autonomy is no longer expressed. ‘…without him live no life. ’ (833) • Eve tries to convince Adam that she ate from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil for his sake: ‘which for thee / Chiefly I sought’ (877878). Eve becomes a little like Satan here. We see how her ambition has left her completely vulnerable to Satanic influence. • Despite Eve’s attempts to persuade Adam her guilt cannot be hidden. ‘But in her cheek distemper flushing glowed. ’ (887)

Lines 914 – 1006 • In these lines we see Eve’s remorse, her ambition now gone as she begs Adam for some forgiveness. ‘. . unweeting have offended, / Unhappily deceived; thy suppliant / I beg, and clasp thy knees. . ’ (916 – 918) • We see the misguided nature of Eve’s ambition for autonomy. Earlier in Book 10, God says to Adam, ‘Thou didst resign thy manhood, and the place / Wherein God set thee above her made of thee, / And for thee. . ’ (148 – 150) Adam is at fault for not ruling over Eve.

Context: Milton’s views on women and marriage • 17 th C. views on the relationship between a husband wife saw it as mirroring the relationship between King and subject: ‘the family was a little church, a little state… the subordination of the wife to the husband figured Christ’s rule over the state’. Christopher Hill (Milton and the English Revolution 1977). • Milton seems to have endorsed this view after marrying his first wife in 1642. She was much younger, and quite different, to him, and seemingly unwilling to play a traditional ‘wifely’ role. It was after this experience that he wrote the Divorce Tracts. • ‘What an injury is it after wedlock not to be beloved… to be contended with… not for any parity of wisdom… but of female pride’ – Milton in the Divorce Tracts on his first marriage. • He eventually took her back, after a display which saw her, “making Submission and begging Pardon on her Knees before him”. Could we compare this to Eve’s supplication (begging forgiveness) before Adam in Book 10? God punishes Eve for her disobedience by giving Adam power over her – this was not the case in the Eden.

• However, his view of women perhaps changed after his second marriage, to Katherine Woodcock. She died two years into their marriage, but he loved her deeply, and, interestingly, also felt “intellectual delight” at their union. • Women in the 17 th Century were becoming more generally educated and autonomous. In On Christian Doctrine Milton would even considers that a woman may be wiser in the marriage than a man. • C. S. Lewis (Christian critic, and of Narnia fame), was a vehement anti-feminist critic of Eve’s: “Eve fell through pride…Godhead is what she thinks of when she eats. ” • Lewis goes on, even more damningly: “She decides that if she is to die, Adam must die with her… the precise sin which Eve is now committing… is murder. ”

Eve and the Duchess Ambition and its Dangers The Duchess: • Act 1 Scene 1 line 304 – 517 from Exit Bosola, Enter Duchess and Cardinal to the end of the scene. • Act 3 scene 2 line 69 – 142 from [Sees Ferdinand who holds a poniard] to [Exit Ferdinand. Enter Antonio with a Pistol, and Cariola] • Act 3 scene 5 lines 95 – 144 from ‘O, they are very welcome. ’ to the end of the scene. • Read through these lines exploring how the Duchess’ ambitions are expressed. What view of ambition is Webster giving? • Identify and explain key quotations.

The Duchess Act 1 Scene 1 line 304 – 517 • We see Ferdinand commanding his sister, the Duchess in regards to her role, ‘You are a widow: / You know already what man is, and therefore / Let not youth, high promotion, eloquence –’ He is forbidding her from having a relationship. (305 – 307) • The Duchess shows her defiance and her ambition for autonomy, ‘If all my royal kindred / Lay in my way unto this marriage, / I’d make them my low footsteps. ’ (353 – 355) Their opposition merely strengthens her resolve, showing her desire for self-determination. She is not prepared to be directed by will of her brothers. She rejects patriarchal control.

The Duchess Act 1 Scene 1 line 304 – 517 • ‘The misery of us that are born great: / We are forced to woo, because none dare woo us’ (453 – 454). Duchess expresses her frustration at the confining nature of her role. • ‘I do put off all vain ceremony, / And only do appear to you a young widow / that claims you for her husband’ (467 – 469). Here she breaks with the confining conventions of tradition. Her proposal to Antonio is very demanding.

The Duchess - Act 3 scene 2 line 69 – 142 • ‘I pray, sir, hear me: I am married. ’ (82) Her short, bold statement to Ferdinand is defiant. • ‘Why might not I marry? / I have not gone about, in this, to create / Any new world, or custom. ’ (109 – 111) Her questioning of Ferdinand challenges his authority. She defends her right to marry as she chooses. • ‘Why should only I, / Of all the princes of the world, / Be cased up, like a holy relic? ’ She equates herself here with all sovereigns (interesting how she uses the male term ‘princes’), implying that she should not be stifled because she is a woman.

The Duchess- Act 3 scene 5 lines 95 – 144 • The Duchess is informed by Bosola that she is to be confined to her palace. Bosola says that her ‘brothers mean you safety and pity. ’ • The Duchess responds, ‘With such a pity men preserve alive / Pheasants and quails, when they are not fat enough / To be eaten. ’ She is now fully aware of her powerlessness. The bird/game imagery shows her understanding that she is being kept until the time is right for her to be killed.

The Duchess- Act 3 scene 5 lines 95 – 144 • In the Duchess’ closing speech at the end of Act 3 scene 5 she relates a tale concerning a salmon and a dog fish. The dog fish sees the salmon as a social inferior. The salmon responds, ‘Thank Jupiter we both have passed the net. / Our value can never be truly known / till in the fisher’s basket we be shown. ’ (135 – 137) Here the Duchess shows her understanding that freedom is more valuable than social status. High status makes you valuable to those who can profit from you. • At this stage the Duchess knows that she is doomed and her ambition for autonomy and self-determination have led to her destruction. However, she never expresses regret for her actions.

Duchess of Malfi – Social Context The beginnings of social change in Malfi: • Critics such as Frank Whigam have suggested that Jacobean society might be seen as a period of social change, indicated by a new social and sexual mobility (seen in Julia) • Jacobean society, reflected in Malfi, was one where honours could be bought and sold, so ancestry was of less social significance and individuals could rise through the ranks of society. • As London was a centre of economic growth, the new wealth changed traditional class types; boundaries which had existed for years between the middle and upper classes were being challenged by the rise of the bourgeoisie.

• The Elizabethan acceptance of the ‘Great Chain of Being’ which claimed that social strata, having been established by God, were eternal and unchangeable was beginning to fade. Once a king sold honours (as James I did), he could no longer be seen as the representative of God, because he had usurped God’s powers. • Webster presents in Ferdinand an embattled representative of the older way of life, an almost feudal aristocrat who can see his world disintegrating in front of him (empathy generated? ) • The Duchess has the spirit of the new, is ready for change, and promotes people through merit rather than birth. (Bosola: “Can this ambitious age / Have so much goodness in’t as to prefer / A man merely for worth…? ”. Antonio is the ‘new man’, rising through his own merit, while Bosola is an example of the unfortunate group who are intelligent, sensitive and educated but are unable to find an appropriate role in society. • To ensure that their bloodline and wealth survive, aristocrats rely on suitable marriages; so when the Duchess marries without a “clew” or “guide”, she is breaking new ground (social pioneer like Eve – “Let us divide our labours”)

• There was one prominent case in which a clandestine marriage was handled with particular severity: the case of Lady Arbella Stuart(1575 -1615) , who was in the line of royal succession and therefore needed permission of James I to marry. When the King refused to marry Lady Arbella off she took matters into her own hands and secretly married William Seymour. Lady Arbella was caught and thrown into the Tower of London, where she eventually went mad and died. • She wrote a letter from prison declaring her equal rights and accusing James I as acting above the law, ‘I may receive such benefit of justice as both his majesty by his oath those of his blood not excepted hath promised and the Laws of his realm afford to all others, ’ this challenge to James I was an act of real rebellion for a woman of the period. • Arushi Mather (2015): ‘In light of Renaissance social standards, the Duchess flouts patriarchal authority by marrying without the approval of male members of her family, she violates decorum by remarrying and by choosing a mate below her in station, and she reveals an overt and dangerous female sexuality, all of which threaten the social order. ’

Eve and the Duchess Similarities Both Eve and Duchess could be perceived as ambitious – both want to raise their status to that of their male counterparts / have agency/ autonomy. Both Eve and Duchess challenge patriarchal societies and the limitations placed on them. Eve goes further as she wants knowledge comparable with that of God. However, both are only able to achieve their desires in secret. Both are motivated by desire and this impacts negatively on their ambitions to raise their status: Eve is naïve and the Duchess’ love for someone beneath her status endangers her. Duchess dies – her ambition to raise her status is thwarted Eve suffers the consequences of her ambition to challenge God’s authority losing her (and Adam’s immortality)

Eve and the Duchess Differences • Duchess is able to outwit her brothers at certain points and ultimately she forgives her brothers or at least accepts her fate (‘Tell my brothers / That I perceive death, now I am well awake / Best gift is they can give, or I can take. ) suggesting that she has managed to raise her status to be perceived as their equal – contemporary audiences might see her as superior. This reflects the idea that Webster is challenging social structures of the time • Whereas, Eve is left to suffer the harshest consequences, even more so than Satan. This links to the patriarchal mores of the time and ideas of the natural subjugation of women. This reflects Milton’s more didactic approach and puritanical concerns.

Satan and Bosola Ambition and its Dangers Satan’s flawed means to ambition engender his decline: he is no longer the statesman and military leader of Books I and II, but a deconstructive consciousness, eaten up with envy and malice. Satan: Book 9 Lines 99 – 178 from ‘O earth, how like to heaven, if not preferred’ to ‘From dust: spite then with spite is best repaid’ Lines 473 – 512 from ‘Thoughts, wither have ye led me, with what sweet compulsion’ to ‘to interrupt, sidelong he works his way’ Book 10 Lines 383 – 584 from ‘whom thus the prince of darkness answered glad’ to ‘And Ops, ere yet Ditaean Jove was born. ’ Read through these lines exploring how Satan’s ambitions are expressed. What view of ambition is Milton giving? Identify and explain key quotations.

Context: Charles I, Oliver Cromwell, The English Civil War • His writings became increasingly political during the ‘eleven years of tyranny’, under Charles I, of 1629 -1640, and during the English Civil War (1642 -49). He was involved in the opposition to King Charles I, whom he perceived as a tyrant. Charles I was executed in 1649, and England entered its only period as a Republic (rule by parliament, without a monarch). • During Charles I trial, he wrote a highly controversial tract endorsing the revolutionary act of regicide (killing a king) in certain circumstances. This was a spectacular rejection of the Divine Right of Kings! Like the Puritans, Milton saw Charles as a usurper, and rejected the Divine Right theory. • For Milton, abolishing Kingship was a step back towards the original freedom of Adam – a chance to be obedient to God, our true master, rather than a tyrannical King. Adam’s freedom to Fall was evidence of his freedom: “all men naturally were born free, being the image and resemblance of God himself”.

• The civil war saw the Parliamentarians and their New Model Army, many of whom were deeply Puritan in their outlook, fighting the Cavaliers or Royalist supporters of Charles I. • The Puritan belief, shared by Milton, was that no man is another’s superior – that all forms of authority other than God’s are therefore suspect. • Oliver Cromwell, ruler of Republican Britain, was as unwilling to share power with parliament as Charles I had been, and proved himself a similar tyrant. On his death, disaffected MPs asked Charles I’s son, Charles II, to take throne. • Milton was very disappointed at the return to monarchy, feeling the English had feebly given away their newly appointed freedom. He wrote about this, and was briefly imprisoned for it by Charles II. • Around this time he began writing Paradise Lost. By 1652 his eyesight had failed him completely, so he dictated the work to his daughters. • He put into Satan’s mouth many of his and his fellow republican’s arguments against the tyranny of leaders (for Satan, God; for Milton, Charles I). Like Cromwell, however, Satan reveals himself to be the true tyrant. Satan, perhaps like Cromwell, is attractive and destructive for Milton.

The duchess of malfi introduction

The duchess of malfi introduction Luke 15:11-35

Luke 15:11-35 Jacobean and caroline prose

Jacobean and caroline prose Surprised by sin the reader in paradise lost

Surprised by sin the reader in paradise lost Paradise lost background

Paradise lost background Epic conventions in paradise lost

Epic conventions in paradise lost Paradise lost date

Paradise lost date Paradise lost milton summary

Paradise lost milton summary Paradise lost in cyberspace

Paradise lost in cyberspace Samuel johnson paradise lost

Samuel johnson paradise lost Paradise lost iambic pentameter

Paradise lost iambic pentameter Paradise lost and found

Paradise lost and found Context of paradise lost

Context of paradise lost Samuel johnson on paradise lost

Samuel johnson on paradise lost The fall of satan paradise lost

The fall of satan paradise lost What does satan vow

What does satan vow Paradise lost theme

Paradise lost theme Once was lost now i'm found

Once was lost now i'm found Frankenstein paradise lost

Frankenstein paradise lost Paradise lost review

Paradise lost review Sin and death paradise lost

Sin and death paradise lost Mans first disobedience

Mans first disobedience Albrecht durer paradise lost

Albrecht durer paradise lost Albrecht durer paradise lost

Albrecht durer paradise lost Re zoom 게임

Re zoom 게임 Zoom meeting

Zoom meeting Zoom login

Zoom login Support zoom enus

Support zoom enus Spu zoom

Spu zoom Zoom snu

Zoom snu Zoom simultaneous interpretation function

Zoom simultaneous interpretation function