Why exercising matters educationally An investigation into school

- Slides: 26

Why exercising matters educationally. An investigation into school practices from the perspective of Stein’s automatic writing experiments Joris Vlieghe Laboratory for Education & Society University of Leuven (Belgium) joris. vlieghe@ppw. kuleuven. be

Why exercising matters educationally • Philosophical perspective on the ‘practice of practising’ (Üben): collective learning activities that require repetition • Background: earlier research on the role of the body in and for education, on the basis of Giorgio Agamben • Objective: the development of an alternative framework for looking at class-room practices, that - asks attention for a corporeal dimension, and more specifically the body that is ‘on the other side of meaning’ - is really concerned with the educational significance of school practices instead of considering them as pedagogical tools that should be evaluated in terms of effectiveness

Overview • looking at a practice as a pedagogical tool vs. looking at it at as an educationally significant activity • An extreme case: Gertrude Stein and the practice of automatic writing - how we should an how we should not understand it • Some conclusions regarding the sense of practising

Pedagogical tool or educationally relevant practice? • Discussion at my university regarding the ‘millennium student’ (student grown up in a digital age): should we leave traditional teaching and learning methods behind in favour of digital ones • Argument: psychological research has shown that people can only keep their concentration for 15 minutes, rates of retention drop increasingly after 20 minutes of attending college, etc. • My reply: this regards an abstract concept of attention measured in experimental conditions. In real life students developed means to stay attentive, like taking notes.

Pedagogical tool or educationally relevant practice? • Reply to my reply: how stupid can you be? Don’t you know, psychological research has shown that, when taking notes, it is only possible to write a small percentage of it down? The practice of taking notes is obsolete, it’s proven that it is highly unproductive. End of discussion. • This ‘discussion’ shows for me that, if we start from the premise that everything that happens in a class-room should be judged in terms of measurable learning outcomes, we might miss the educational meaning of school practices • My point was not to prove that note-taking was an efficient solution to the problem of how to guarantee or improve learning outcomes. Note-taking can be analyzed as a practice through which students form and transform, i. e. ‘educate’ themselves.

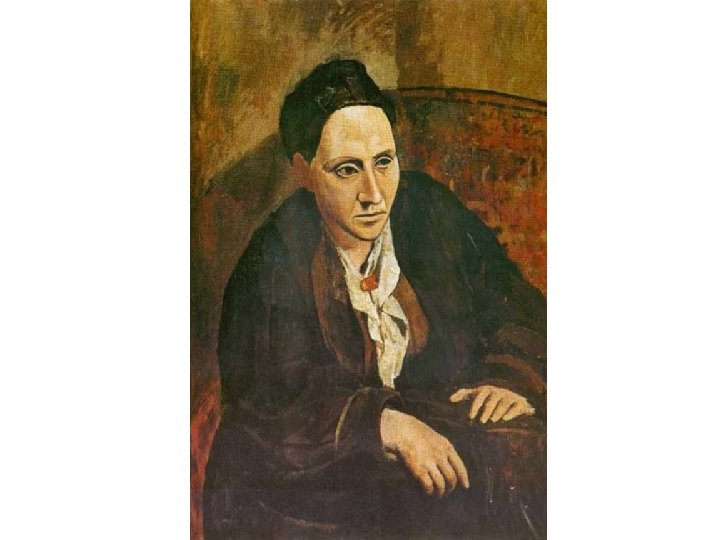

Automatic writing • Looking at the practice of writing as something else than a mere (pedagogical) tool → extreme case of writing that is pointless: Gertrude Stein’s (1874 -1946) experiments with automatic writing: practice of writing that has no functional significance whatsoever • Although she later became one of the most important 20 th Century writers, Stein began as a student in psychology at Harvard, where she worked under the supervision of William James. • Different experiments (1890’s) with writing during moments of distracted attention: writing becomes an automatic event (cf. : doodles)

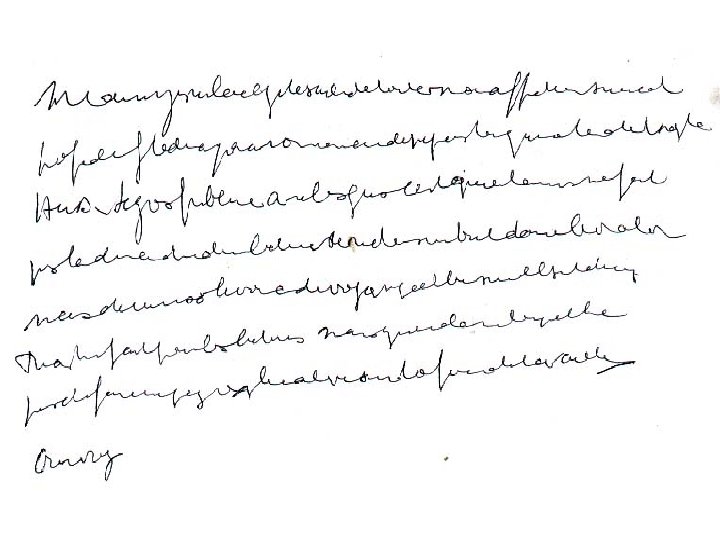

• Self-directed experiment: while simultaneously reading an engaging text, one has a pen in one’s hand some paper to scribble on (after training session, each session 20 à 30 min. ) • “Sometimes the writing of the word was completely unconscious, but more often the subject knew what was going on. His knowledge, however, was obtained by sensations from the arm. He was conscious that he just had written a word, not that he was about to do so. ” • “Habitual acts […] may go on outside the field of consciousness. […] For them not only volition is unnecessary, but consciousness as well is entirely superfluous”. • Writing without any sense of destination

Automatic Writing • This practice was taken up again and vulgarized by the Surrealist and Dadaist movement (1920’s), and notably by the French poet André Breton. • The aim was to reconnect with and to set free a more originary and authentic part of the self (one’s ‘true being’, a source of spontaneity and creativity, we have forgotten to possess due to modern (technological and rational) ‘civilization’. • Ironically, the Surrealists put their fate in a mechanized process of writing in order to set the part of the self free that was suppressed due to the mechanization of our life-conditions • Today still practiced by spiritualists movements

Background of Stein’s experiment • Background of Stein’s experiments was the late romantic idea that two (or more) selves might live in one and same body. This had become a dominant cliché, exemplified by R. L. Stevenson’s highly influential novel Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hide (1886). • Cf. : George Santayana, William James (Stein’s professors): ‘second personality’ as the origin of (artistic) genius • The ‘psychic’ became the object of scientific research, cf. the foundation of the Society for Psychical Research by Frederic Myers in 1882 • Myers furthermore argued that automatic writing might perhaps not only assist one in discovering a secondary personality, but in creating a secondary self (e. g. by taking up the habit of writing letters while being drunk)

Stein’s conclusions • Stein discovers in her experiments something that is precisely opposed to these romantic ideas – and also opposed to the objective of Breton’s surrealist experiments • Automatic writing = practice of writing, divorced from any conscious intention, but also disconnected from unconsciousness. • While writing automatically, we find ourselves in a condition “in which the subject has not the faintest inkling of what he has written, but feels quite sure that he has been writing. It shows no tendency to pass beyond this into real unconsciousness. It seems to depend on the lack of associations between the different words – one word going out of the consciousness before another has come to be associated with it. ”

Stein’s conclusions • Point ≠ the expression of a deeper message = level of distraction that allows for a disconnection of utterance and intention • Production of meaning that comes literally from nowhere or from nowhere else than from the bodily activity of writing itself • This disconnection grants the possibility to relate to our own practice of writing in a completely unusual way: we witness the mechanics of language (which normally remains implicit) • What is at stake is writing as writing, i. e. writing as an entirely bodily activity and as a mechanical production of meaning Cf. Stein’s 1935 essay How Writing is Written?

Stein’s conclusions • It is due to (and only due to) a suspension of intentionality and meaning that we might connect with this ‘pure’ form of writing • Where ‘pure’ ≠ rediscovery of a deeper self or more authentic practice = manifestation of writing as such • We experience a tacit background of normal life, “a general background of sound, not belonging to anything in particular”, a “bottom nature” that is beyond meaning

How NOT to understand Stein’s experiments • Romantics and Surrealists alike are inclined to look for something behind our actions when these actions lack meaning • It is as if there must be some intentional, meaning-constituting source that explains what we do. And therefore we invent something like a deeper self, a second personality, genius or the unconsciousness. • It is as if we cannot bear the idea that there is nothing behind that what our bodies are able to do (i. e. produce meaningful signs) Cf. Rose is a rose

How NOT to understand Stein’s experiments • Cf. Deleuze’s comments on Spinoza: “we don’t know what a body can do”. . . • . . . and therefore we always try to tame this body by subordinating it to the logic of the intentional consciousness (there must be a reason after all, and if we don’t find one, we just invent some fictions like the unconsciousness. ) • The problem with this kind of approach is that we might stay blind for a dimension of corporeality, viz. bodily experience and action that is wholly ‘on the other side of meaning’ • And, perhaps, precisely this dimension is educationally significant

From Stein to the educational My main concern here ≠ holding a plea for automatic writing = drawing attention to aspects of practices (writing, but also others) that are ‘beyond meaning’ (and that shouldn’t be reduced to a deeper/hidden source of meaning) = trying to understand this ‘beyond meaning’ not in a purely negative manner, but also positively as a condition of potentiality

Potentiality (Agamben) • NOT ‘possibility’ in the superficial sense of that word: mere actualization of capabilities that are already there (e. g. : I can write this or I can write that) • BUT possibility understood as such, e. g. the experience that I can [write] • To experience this, exceptional conditions are required, such as the experimental conditions in which automatic writing might take place • More specifically, any relation with the actualization of concrete possibilities must be put in suspension

Potentiality (Agamben) • True potentiality = impotentiality - this is to say that from the standpoint of intentional consciousness we no longer ‘can’ [do this or that] ↔ at the same time, from the standpoint of the body, we may affirm that we can • Such an experience is in and of itself educational: - not in the sense of the efficient realization or optimization of learning outcomes - but in the sense of experiencing that real (self-) transformation is possible: there is no necessity in the given order of things

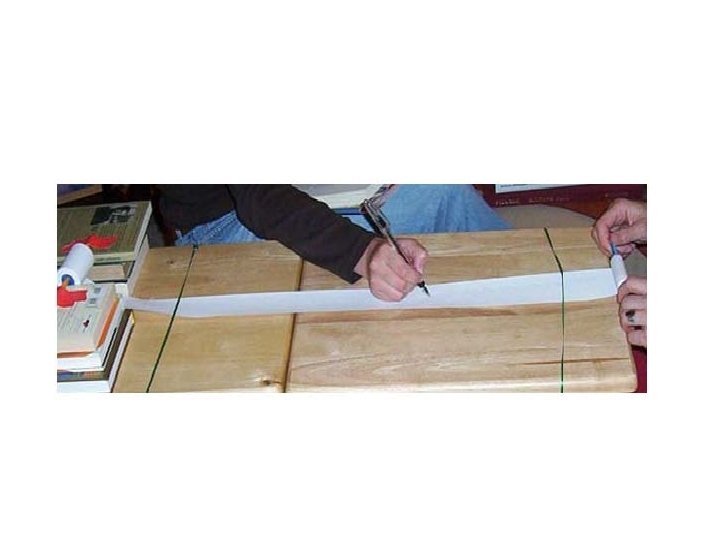

The practice of practising • My suggestion is to understand a whole range of (traditional and perhaps no longer existing) school-practices from this angle, viz. practising • These are typically repetitive activities to be performed in group and under the supervision of a teacher who guarantees a certain rhythm and a harmonization of bodily action • Repeating the alphabet, learning to master multiplication tables, gymnastics, etc.

Common adversity to practising • Due to the popularity of constructivist learning theories we are immediately inclined to disregard theses practices as obsolete. They are understood to be inefficient and to exclude intrinsic motivation. • Perhaps they are still supported as long as they have a mere supportive role vis-à-vis real learning and teaching activities. But when one day instructional psychologists devise more stimulating alternatives, we may finally stop using these dreary techniques

Practising beyond functionality and meaning • This last view on practising is of course very functional • However, I argue for an alternative view, viz. that practising is in and of itself educational • This is because practising is an activity during which the intentional subject precisely disappears in favour of an aggregation of bodies that do exactly the same thing at the same time. This allows for an experience of potentiality • As bodies we might experience that we can count, we can move, we can write (potentiality). And this is due to a suspension of any meaning or functionality whatsoever: we just move, we just count, we just write.

Practising beyond functionality and meaning • In that sense it also intrinsically a democratic experience, not in an institutional sense, but in the sense that we can no longer appropriate the potentiality of what we are doing (moving, counting, writing) as our own private property. • Precisely this grants the possibility of a true transformation, i. e. that something ‘new’ comes into being. More concretely, we might sense that the future is not necessarily structured according to the existing/established societal order. Everything can begin anew, and in regard to this possibility we are equal.

Teaching and bodily gestures • To illustrate this, we might consider the gesticulations of a (typically: passionate) teacher • Again, these gestures might be seen in a mere functional way, i. e. - as an unwelcome nuisance, something that distracts pupils, or - as supporting his/her instructional competences, as a body-language that underlines important things etc. • However, I would say that these gestures constitute in themselves a democratic way of teaching: losing oneself in pointless gestures while commenting on a subject matter, this form of self-loss literally demonstrates that the subject matter at hand (‘the world’) is there for everyone and for no one in special.