TRENDS IN SECONDHAND SMOKE EXPOSURE AMONG SOUTH AFRICAN

- Slides: 19

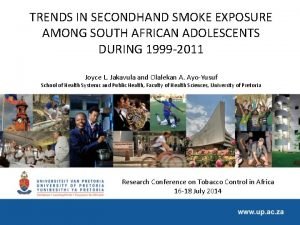

TRENDS IN SECONDHAND SMOKE EXPOSURE AMONG SOUTH AFRICAN ADOLESCENTS DURING 1999 -2011 Joyce L. Jakavula and Olalekan A. Ayo-Yusuf School of Health Systems and Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Pretoria Research Conference on Tobacco Control in Africa 16 -18 July 2014

What do we know about SHS? • SHS contains >4, 000 chemicals and is responsible for over 600, 000 annual deaths. In 2004, 40% of children were exposed to second -hand smoke -- 33% of male non-smokers and 35% of female non-smokers. • Exposure leads to heart disease, bronchitis, pneumonia, asthma and lung cancer. Oberg et al, 2011; U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2006.

Interventions to reduce SHSe • Tobacco control strategies are designed to influence individual behaviour and change social norms about tobacco use. • Protect non-smokers, encourage smokers quit and remain abstinent and discourage smoking initiation among youth.

Smoke-free policies in SA • SA has smoke-free policy but currently allows for designated smoking areas. • ‘Scientific evidence indicates that there is no risk-free level of exposure to secondhand smoke. Breathing even a little secondhand smoke can be harmful to your health. ’ (U. S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2006). • Regulations to go 100% free of smoking are been reviewed.

SA non-smoking adolescents’ exposure to SHS • SA studies show that there is a reduction in SHSe in homes from 32. 1% in 1999, to 26. 2% in 2002 and 25. 7% in 2008. SHSe outside the homes decreased from 41. 2% to 32. 4% then increased to 34. 3% outside the home. – Exposure within the 7 days preceding the survey. Peltzer, 2006; Swart et al. , 2003; Reddy and Swart, 2003 • Not aware of studies which looked at trends of regular exposure (5 -7 days) before and after the implementation of the 2001 partial ban

Objectives of study To determine the trends of regular exposure to SHS and examine mediators of change among non-smoking SA adolescents

Methods • Secondary data analysis of nationally representative samples of the Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS), a school based survey administered to learners in grades 8 -10 (13 -15 years) to assess their use of tobacco products and exposure to SHS. • 4 surveys conducted in SA: 1999, 2002, 2008 and 2011 – The datasets were merged to explore trends – Data collected included participants’ demographic characteristics; and behaviour, knowledge and attitudes to SHS.

Methods (cont. ) • Main outcome measure: ‘Regular exposure to SHS’, defined as reporting exposure to SHS at home and/or other places for at least 5 out of 7 days preceding the survey. • Data analysis was restricted to non-smokers (n=24, 559), included Chi-square statistics, Wald trend tests and logistic regression analysis. • Joint point was used to determine annual percentage change in exposure over time. • Using SPSS v 22, all data analysis took into account the cluster sampling design used in GYTS. • Level of significance was set at <5% (2 -tailed tests).

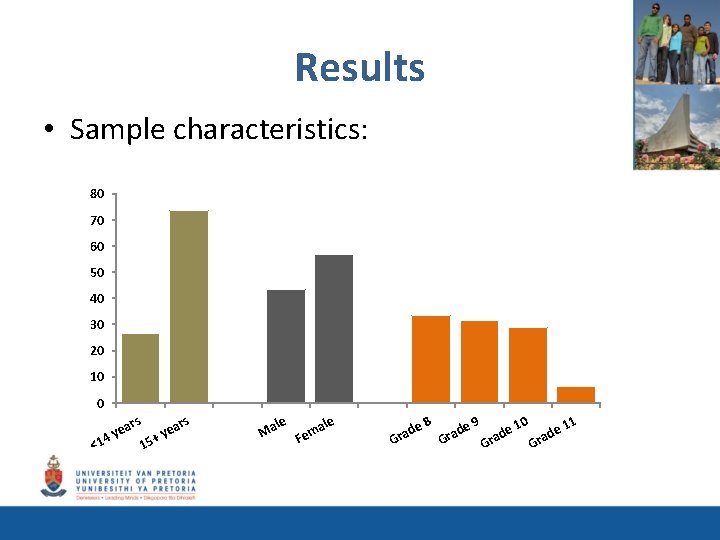

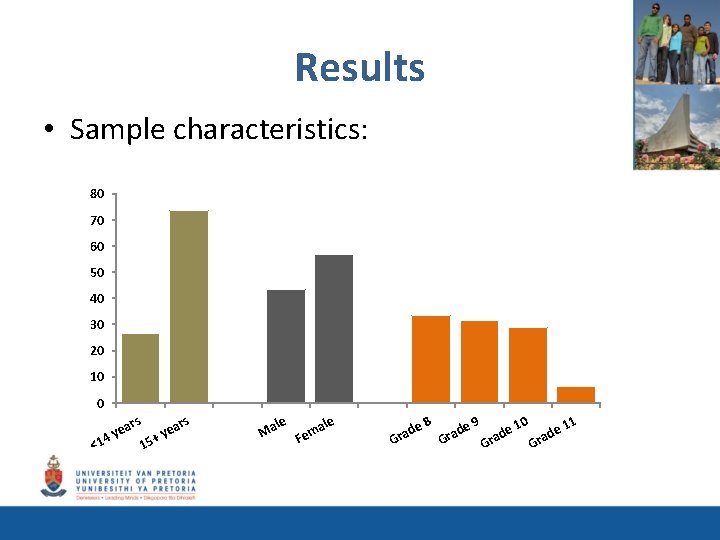

Results • Sample characteristics: 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 rs <1 ea 4 y 15 s ear y + le Ma a Fem le de a r G 8 de a r G 9 G e rad 10 G e rad 11

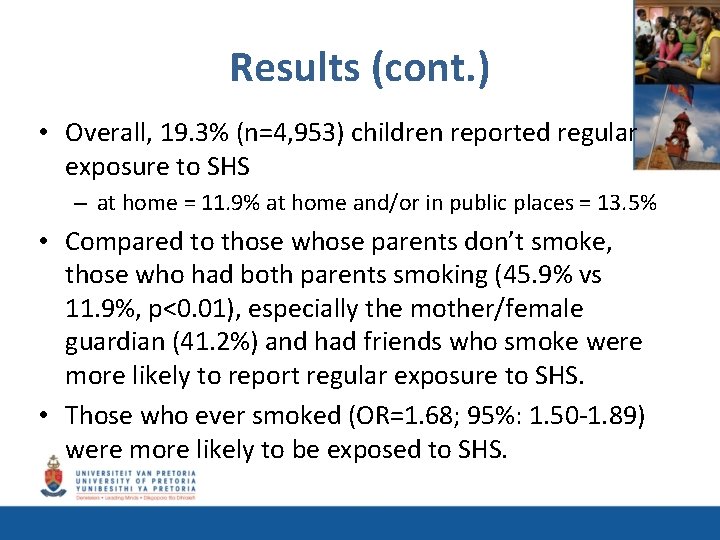

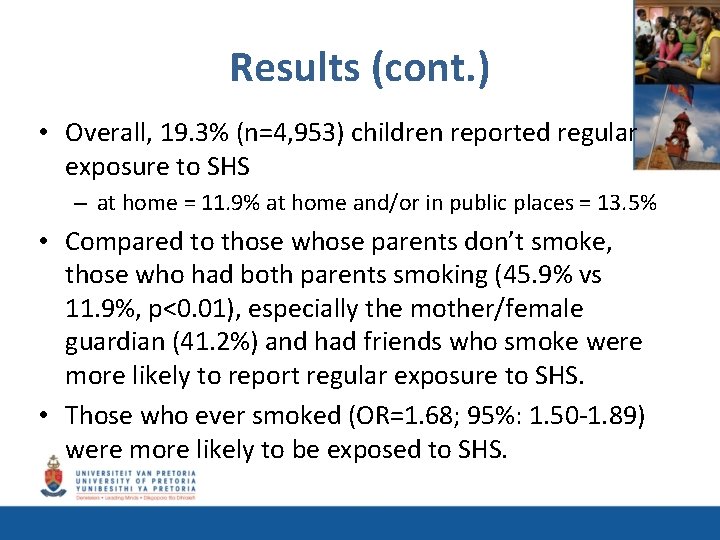

Results (cont. ) • Overall, 19. 3% (n=4, 953) children reported regular exposure to SHS – at home = 11. 9% at home and/or in public places = 13. 5% • Compared to those whose parents don’t smoke, those who had both parents smoking (45. 9% vs 11. 9%, p<0. 01), especially the mother/female guardian (41. 2%) and had friends who smoke were more likely to report regular exposure to SHS. • Those who ever smoked (OR=1. 68; 95%: 1. 50 -1. 89) were more likely to be exposed to SHS.

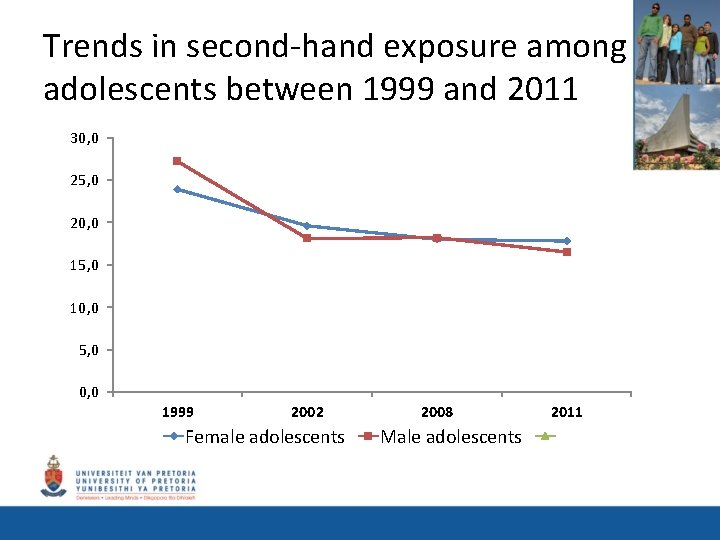

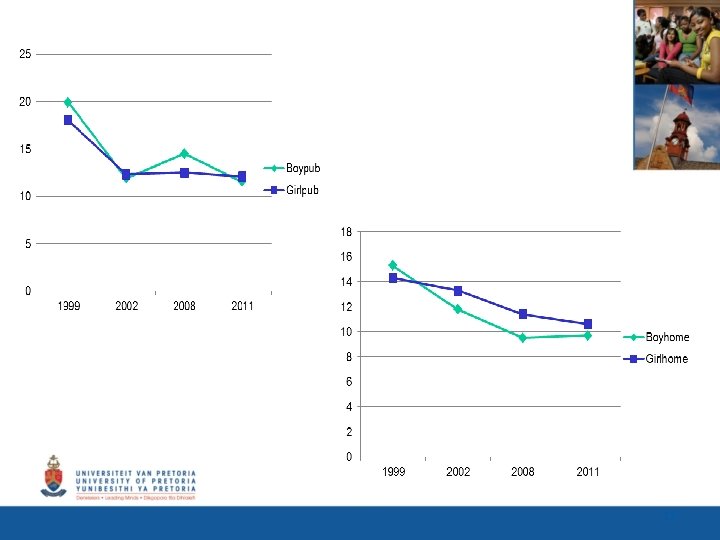

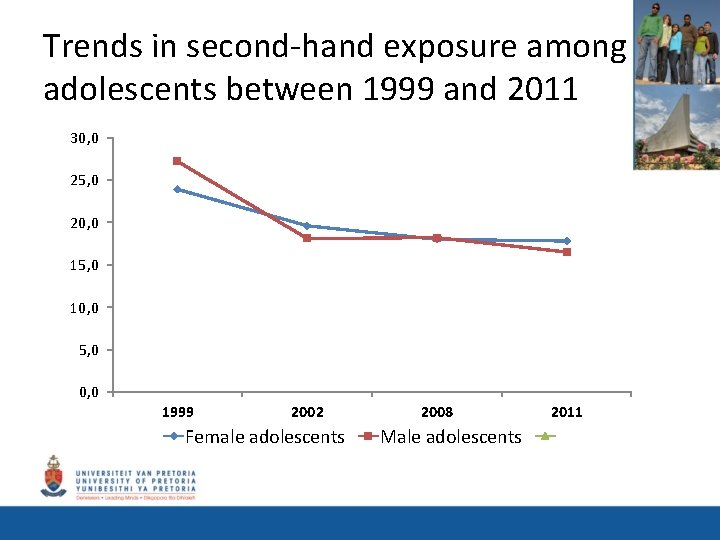

Trends in second-hand exposure among adolescents between 1999 and 2011 30, 0 25, 0 20, 0 15, 0 10, 0 5, 0 0, 0 1999 2002 Female adolescents 2008 Male adolescents 2011

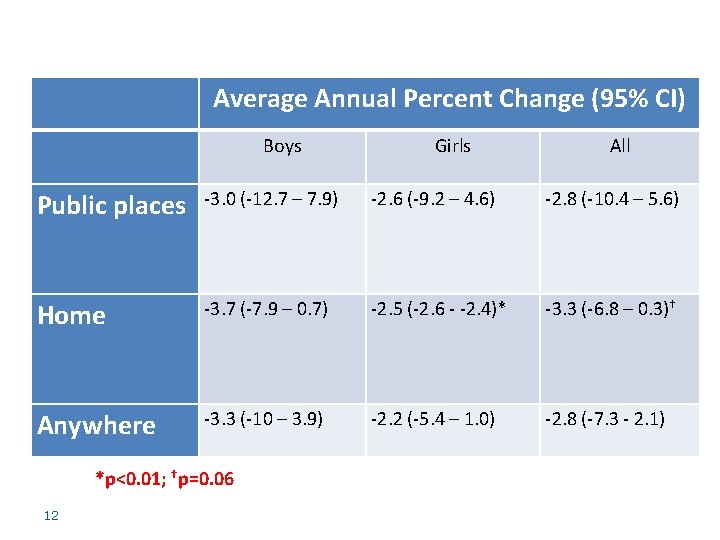

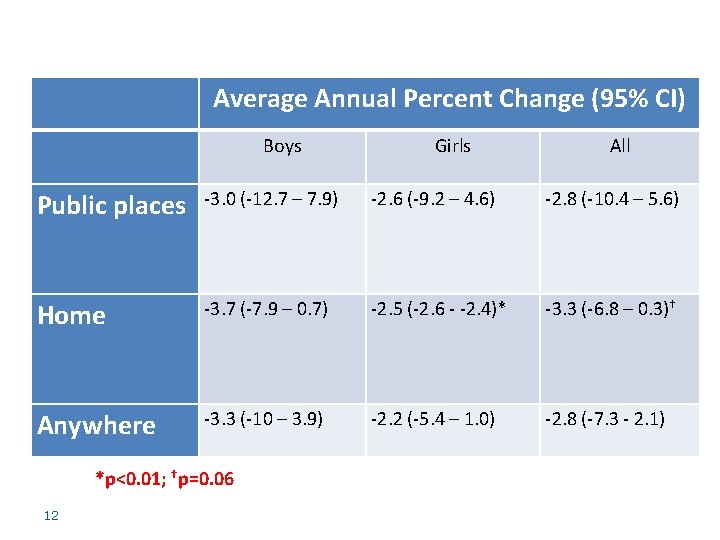

Average Annual Percent Change (95% CI) Boys Girls All Public places -3. 0 (-12. 7 – 7. 9) -2. 6 (-9. 2 – 4. 6) -2. 8 (-10. 4 – 5. 6) Home -3. 7 (-7. 9 – 0. 7) -2. 5 (-2. 6 - -2. 4)* -3. 3 (-6. 8 – 0. 3)† Anywhere -3. 3 (-10 – 3. 9) -2. 2 (-5. 4 – 1. 0) -2. 8 (-7. 3 - 2. 1) *p<0. 01; †p=0. 06 12

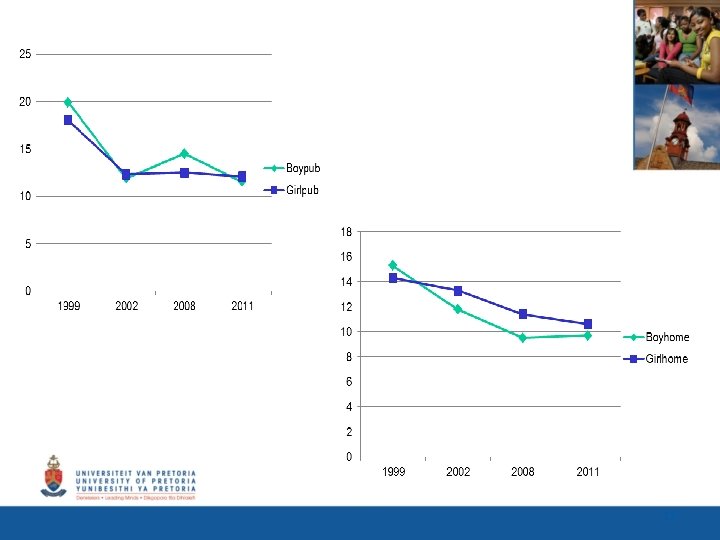

13

Discussion • • SHSe among non-smoking adolescents decreased between 1999 and 2002; not much change. The decline in children’s exposure to SHS could be mediated by a decline in proportion of children reporting smoking parents and friends which could be due to: • • • Increase in taxes during the same period (1997) Legislation such as the ban itself (2001) More SA children remain exposed to SHS outside their homes than in their homes

Limitations • Self-reported information, possible bias. • School-based and therefore not representative of all adolescents in SA.

Conclusions • Need for targeted interventions to reduce SHSe -parental/guardian, especially females and discourage youth from starting. • Advocate for 100% smoke-free public places.

References 1. Öberg M, Woodward A, Jaakkola MS, Peruga A, Prüss-Ustün A: Worldwide burden of disease from exposure to second-hand smoke: a retrospective analysis of data from 192 countries. Lancet 2011, 377: 139 -146 2. US Department of Health and Human Services. The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: A report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA. CDC; 2006. 3. Swart, D. ; Reddy, P. ; Ruiter, R. A. C. ; de Vries, H. Cigarette use among male and female grade 8– 10 students of different ethnicity in South African schools. Tob. Contr. 2003, 12, 1 -5. 4. Reddy, P. ; Swart, D. Preliminary Report on the Global Youth Tobacco Survey: 2002. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

THANK YOU!

References • • • Oberg M. , Jaakkola M. S. , Woodward A. , Peruga A. , Pruss-Ustun A. Worldwide burden of disease from exposure to second-hand smoke: A retrospective analysis of data from 192 countries (2011) The Lancet, 377 (9760) , pp. 139 -146. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)/World Health Organization (WHO) (2008). Global Youth Tobacco Survey (GYTS). Atlanta GA (http: //www. cdc. gov/tobacco/global/gyts/index. htm, US Surgeon General (2006). The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta GA, US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health.

Managing economic exposure and translation exposure

Managing economic exposure and translation exposure Managing economic exposure and translation exposure

Managing economic exposure and translation exposure Operating exposure adalah

Operating exposure adalah Transaction exposure and economic exposure

Transaction exposure and economic exposure What is a secondhand account

What is a secondhand account South african council for the architectural profession

South african council for the architectural profession Saaqis

Saaqis South african principals association

South african principals association The south african apartheid

The south african apartheid South african tax

South african tax South african freedom charter pdf

South african freedom charter pdf South african furniture initiative

South african furniture initiative South african transport conference

South african transport conference South african bont tick

South african bont tick South african plateau map

South african plateau map South african journal of botany impact factor

South african journal of botany impact factor South african transport conference

South african transport conference South african tax

South african tax Dr hamilton surgeon

Dr hamilton surgeon South african council for natural scientific professions

South african council for natural scientific professions