The Sounds of Language u The sounds of

- Slides: 15

The Sounds of Language

u The sounds of language may be studied with special attention to the speaker, the surrounding air or the hearer. u In the first case we study articulatory phonetics, the movement of lungs, vocal cords, tongue, lips, and other organs which initiate and modify the noisy outward breathing which is the physiological reality of language. u In the second case, acoustic phonetics, attention is directed to the sound waves in the air, the physical reality of speech; and in the third case, auditory phonetics, we study the process of perceiving these sounds and the psychology of hearing.

u Attempts have sometimes been made to give a very tidy description of the phenomenon of pause. u In the seventeenth century, Simon Daines, a teacher of music as well as of speech, urged his students to count to one, two, three or four when pausing in reading, though as John Walker observed a century later ‘nothing so regular fits the facts of language’.

u American linguists nevertheless revived, a generation ago, a concept of four significant pause in English speech, and, in order to build up a concept of language based on scientifically observable data, posited that these pauses or ‘junctures’ were always audible. u Very careful speech will distinguish ‘a – name’ form ‘an – aim’, ‘the sons – raise meat’ from ‘the sun’s rays – meet’ and even make the purely grammatical distinction between ‘Good – Friday films, and ‘Good Friday – films’.

u Pause becomes especially important within the special schemes of poetic language. u In poetry an expectation of pause is controlled by line division. If the line has an odd number of ‘beats’ (three or five), the pause is more evident than if there is an even number of beats (usually four). Compare: How pleasant to know Mr. Lear! Who has written such volumes of stuff! with John Gilpin was a citizen Of credit and renown,

u A poet has in his control a double system of (potential) pauses, one controlled by grammar and the other by the ends of his lines. u If the two coincide in ‘end-stopped verse’, there is a reinforcement of pauses; if they do not, there is a kind of counterpoint of the two systems. u Such counterpoint is usual in poetry, and is perhaps what distinguishes ‘poetry’ from ‘verse’, but conventions of enjambement vary from poet to poet and from age to age.

u Pope characteristically finishes a sentence within a rhyming couplet, with an effect of neatness and wit, whereas Milton prefers a majestic sweep down a sequence of run-on lines. u Modern poets even cross the once inviolate boundaries between stanzas.

u The stylistician deals with what the users of a language know and notice, and the users of language have a general, rather than an exact, awareness of syllable structure, feeling that some languages (Italian, especially) are more ‘musical’ than others, or recognizing that five sixths is ‘harder to say’ than a half, noticing, probably, the ‘restrictiveness’ of stop consonants (p, t, k, b, d, g) more than the continuants (l, m, n, r, s, f and other sounds which can be prolonged). u Awareness of all these things is likely to be sharpened and made more precise in poetry.

u Syllables vary in ‘length’ or duration. The syllable band is longer than bat, both because there are more sounds in it and because we tend to lengthen the pronunciation of the a before the voiced sounds n and d. u In the same way, seed has a longer vowel than seat, though few of us notice this because length of vowel alone does not distinguish words in standard English.

u The length (or ‘quantity’) of syllables was more important in early English than it is now. u In modern English, apart from some Elizabethan experimenters, length of syllables does not enter into theoretical metrical pattern of poetry, but the number of syllables does. u A regular line in English verse traditionally has a fixed number of syllables, most commonly eight or ten. u The number of syllables in a word therefore of importance for poetry.

u This may seem straightforward; obviously bake has one syllable, baker two and bakery three. u But how many syllables are there in practically? Or familiar? in older poetry, we may need to ask, further, what was the pronunciation, when the poet wrote, of words that may have changed in pronunciation since his time.

u It is easier to point to the existence of stress than to discover its phonetic nature. u It is easy to hear that baker has stress on the first syllable, cadet on the second. u Contract has stress on the first syllable if a noun, on the second if a verb. u The phrase ‘on the whole’ has stress on the last syllable. u ‘After all’ traditionally has stress on the last syllable, but a recent tendency is to place stress on the first. u The ‘weight’ of a stressed syllable usually appears as an increase in loudness, but not always.

u ‘Thank you’ is normally pronounced with stress on the first syllable, and this is still true in a possible pronunciation in which that syllable becomes inaudible (‘kyou). u There is still a chest pulse, or residual pulse, which is felt as stress by the speaker and even sympathetically felt as such by the hearer, despite the absence of any audible sound. u In the same way it is possible to ‘hear’ silent beats in music, and, according to one theory of metrics, in poetry.

u And important function of intonation in speech is to show the connection between parts of a sentence or between separate sentences. u The proverbial ‘Never venture, never win’ is pronounced with a rise or fall-rise at the word ‘venture’. u In written style, the intonation is likely to be replaced, and the connections between units made explicit, by conjunctions: ‘If you never venture, you will never win’.

u Links between sentences can to some extent be made explicit in a similar way, by using connectives such as therefore, thus, on the other hand, or words referring back to a previous sentence (as the word ‘similar’ does at the beginning of this sentence).

Closing and centering diphthongs

Closing and centering diphthongs Oral sounds and nasal sounds

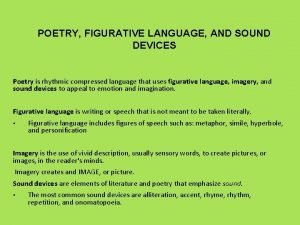

Oral sounds and nasal sounds Sound devices examples

Sound devices examples Language

Language Language refers to the

Language refers to the The sounds of language

The sounds of language Hình ảnh bộ gõ cơ thể búng tay

Hình ảnh bộ gõ cơ thể búng tay Slidetodoc

Slidetodoc Bổ thể

Bổ thể Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em

Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em Chó sói

Chó sói Tư thế worm breton là gì

Tư thế worm breton là gì Bài hát chúa yêu trần thế alleluia

Bài hát chúa yêu trần thế alleluia Các môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng tiếng nhảy

Các môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng tiếng nhảy Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất

Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới