Syntactic Change Syntactic Change Syntactic change refers to

- Slides: 32

Syntactic Change

Syntactic Change • Syntactic change refers to changes in the syntactic structure of a linguistic system. • The most important pathways to syntactic change are: Reanalysis of Surface Structure Shift of markedness Grammaticalization

Reanalysis of Surface Structure • Beyond any doubt, the single most important pathway of syntactic change is reanalysis. • Let’s begin with some simple examples. • Many languages have a special grammatical item called a copula, which serves to link two elements of a sentence, especially two noun phrases (NPs). • The English copula is the verb be, and its use is illustrated by examples like Esther is a businesswoman and Paris is the capital of France. • However, lots of languages have no copula: in Turkish, for example, the sentence Ali büyük means ‘Ali is big’, but it only consists of the name Ali and the adjective büyük ‘big’.

Reanalysis of Surface Structure • Archaic Chinese, the form of Chinese used until about the third century BCE, did not have a copula as shown by the following example; (ye is a declarative particle) Wáng. Tái wù zhe yě Wang -Tai outstanding person Decl ‘Wang-Tai is an outstanding person’ • However, modern Chinese does have a copula in shì: hūa shì hóng flower be red ‘The flower is red’ • nà shì cā That be playground ‘That is the playground’

Reanalysis of Surface Structure • The item shì did exist in Archaic Chinese, but it wasn’t a copula. Instead, it was a demonstrative meaning ‘this’: • shì hóng hūa yě ‘This flower is red’ • zi yù shì rì kū Confucius at this day cry ‘Confucius cried on this day’ • This demonstrative was frequently used in sentences like the following; (suŏ is a particle that nominalizes its clause) • qīan lǐ ér jiàn wáng shì wŏ suŏ yù yě thousand mile then see king, this I Nom desire Decl ‘(To travel) a thousand miles to see the king, this is what I desire’

Reanalysis of Surface Structure • It is precisely this construction that led to the reanalysis of shì as a copula. • Originally X shì Y was literally ‘X, this [is] Y’, but it was reanalysed as meaning ‘X is Y’, and so shì became a copula. • The reanalysis was assisted by the fact that, by the sixth century CE, shì had completely ceased to be used as a demonstrative in any other circumstances such as shì nánhái ‘this boy’ → zhège nánhái, and so from then on it occurred only in sentences like qīan lǐ ér jiàn wáng shì wŏ suŏ yù yě. • Hence constructions such as the following began appearing: • zhège nánhái shì měilì yě This boy is cute

Reanalysis of Surface Structure • A more recent example showing a similar development is Hebrew. • Hebrew formerly had no copula in the present tense, but today it has a copula hu. • David hu ha-ganav David be the-thief ‘David is the thief’ • Mose hu student Moshe be student ‘Moshe is a student’

Reanalysis of Surface Structure • In Hebrew, the source of the copula hu is clear: it is the pronoun hu ‘he’, which is still also a pronoun: • hu ohev et-Rivka he loves Acc-Rivka ‘He loves Rivka’ • A construction with hu, originally meaning literally ‘Moshe, he (is) a student’ has been reanalysed as meaning ‘Moshe is a student’. • ani hu ha-student se-Mose diber itxa alav I be the-student that-Moshe spoke with-you about-him ‘I am the student that Moshe told you about’ • Here the subject is first person, and hu cannot possibly be interpreted as meaning ‘he’.

Reanalysis of Surface Structure • Reanalysis, of course, is not confined to the creation of copulas: it is a pervasive phenomenon in syntactic change. • Let us consider the origin of the English verb form called the perfect. • This is the form constructed with the auxiliary have, as in I have finished my dinner and She had studied in Paris, in which have always combines with the verb form called the perfective participle. • Have is in other respects a common transitive verb meaning ‘possess’: I have a copy of her new book, She has blue eyes. • So how did it come to be an auxiliary, and why a perfect auxiliary in particular?

Reanalysis of Surface Structure • Early Old English shows an interesting stative construction. • Ic hæbbe þone fisc gefangenne I have the fish caught ‘I have the fish caught’ (= ‘I have the fish in a state of being caught’) • Ic hæfde hine gebundenne I had him bound ‘I had him bound’ (= ‘I had him in a state of being bound’) • It is clear that, in such examples that the participles are modifiers of the object NPs, because both gefangenne ‘caught’ and gebundenne ‘bound’ agree in gender, number and case with the object NPs þone fisc ‘the fish’ and hine ‘him’.

Reanalysis of Surface Structure • Very early on, however, the agreement begins to disappear, and the participle stands instead in an invariant form. • Ic hæfde hit gebunden I had it bound ‘I had it bound’ (= ‘I had it in a state of being bound’) • Here the participle gebunden shows no agreement. Crucially, we also find examples in which the stative sense is impossible: • þin geleafa hæfð ðe gehæled your faith has you healed ‘Your faith has healed you’ • Faith, being inanimate, cannot conceivably have (in the sense, ‘possess’, ‘have in my possession’) a person.

Reanalysis of Surface Structure • Ac hie hæfdon þa. . . hiora mete genotudne but they had then. . . their food used-up ‘But they had then used up their food’ • The food, being all gone, cannot be had. • These examples, therefore, cannot be statives: instead, they must be perfects, as shown by the English translations, even though the second one still shows agreement. • The English perfect therefore results from the reanalysis of an original stative construction, in this case accompanied by a shift in meaning.

Shift of markedness • Another important pathway of syntactic change is the shift of markedness. • Languages typically have alternative constructions available for expressing ordinary and not-so-ordinary meanings. • In English, for example, the ordinary (unmarked) word order is SVO as we would therefore normally say I can’t recommend this book, with SVO word order; this is the unmarked form. • For special purposes, however, we can say instead This book I can’t recommend – for example, when comparing the present book with other books. This construction, with an object– subject–verb (OSV) word order, constitutes a marked form.

Shift of markedness • But suppose English-speakers were to begin using this marked form - this book I can’t recommend - more frequently than at present and only occasionally I can’t recommend this book. What would be the result? • First, the OSV construction, being used most of the time, would become the unmarked form, while the earlier SVO construction, being used only occasionally, would become the marked form. • We would therefore have a shift of markedness between the two forms. • English would therefore have undergone a change of basic word order from SVO to OSV.

Shift of markedness • Not so long ago, English had the two prepositions before and behind for expressing position in space, and these were the unmarked forms for expressing position. • But a new marked form in front of was then introduced with the same meaning as before. • This marked form came to be used with increasing frequency, until today it has all but driven before out of the language in its spatial sense. • We can no longer say things like *There is an apple tree before my house. The only possible form is There is an apple tree in front of my house. • The word before still exists, but it is now generally confined to temporal senses, as in before the war.

Shift of markedness • Consider Hebrew. Early biblical Hebrew had two distinct sets of verb forms, called the imperfect and the perfect. • The imperfect forms were used most of the time for most purposes, while the perfect forms were used only occasionally for a few purposes. • Importantly, the imperfect forms normally required verb– subject–object (VSO) word order, the ordinary word order of the language, while the perfect, a marked form, usually required a marked word order, SVO.

Shift of markedness • Here are two examples from the book of Genesis: • va-yiqraʔ ʔelohim la-yabaša ʔerec and-called[Imperf] God to-the-dry land ‘And God called the dry portion “land”’ • ve-ha-ʔadam yada’ʔet hava ʔišto and -the-man knew[Perf] Acc Eve wife-his ‘And Adam knew his wife Eve’ • With the passage of time, however, the perfect, the marked form with SVO word order, began to be used increasingly frequently in an ever larger set of functions, while the imperfect, with its unmarked VSO order, began to lose its functions to the perfect.

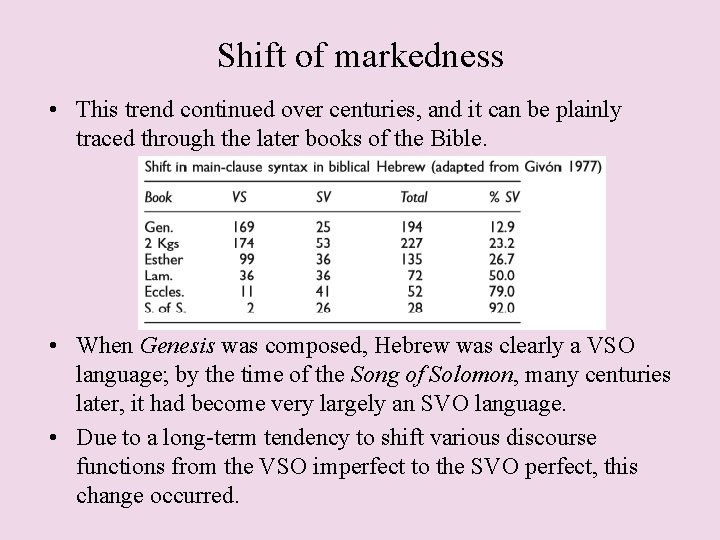

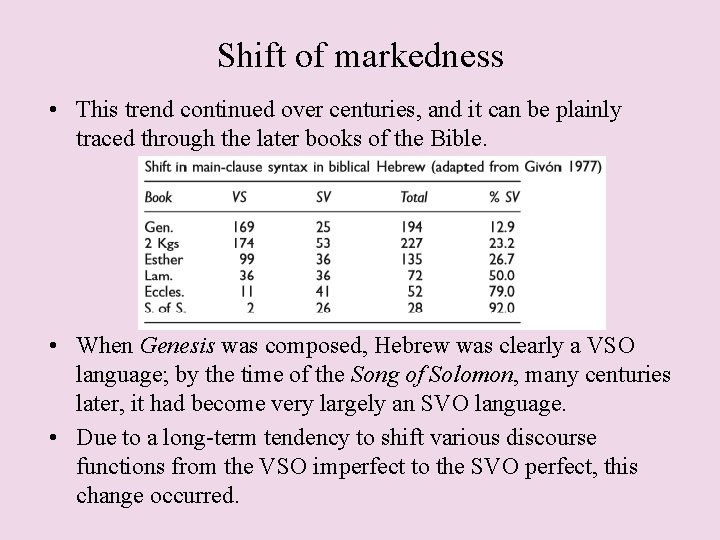

Shift of markedness • This trend continued over centuries, and it can be plainly traced through the later books of the Bible. • When Genesis was composed, Hebrew was clearly a VSO language; by the time of the Song of Solomon, many centuries later, it had become very largely an SVO language. • Due to a long-term tendency to shift various discourse functions from the VSO imperfect to the SVO perfect, this change occurred.

Shift of markedness and Reanalysis • Rather frequently, we find a more complex scenario involving both markedness shift and reanalysis. • Chinese is primarily an SVO language (le is a particle marking completed aspect): • Wŏ dă Zhāng-sān le I hit Zhang-san Asp ‘I hit Zhang-san’ • However, alongside such sentences, Chinese has another construction with SOV word order and a preposition bă marking the object: • Wŏ bă Zhāng-sān dă le I Obj Zhang-san hit Asp ‘I hit Zhang-san’

Shift of markedness and Reanalysis • The SOV order, with its case-marking preposition, seems a very surprising one to find in a predominantly SVO language. • Older Chinese did not have the SOV construction, but it did have a verb bă meaning ‘take hold of, take’. Here is an instance from a ninth-century poem: • Shī jù wú rén shì yīn bă jiàn kàn poem sentence no man appreciate, should take sword see ‘Since no one appreciates poetry, I should take hold of the sword to contemplate it’ • Originally, bă was the verb ‘take hold of’, and such sentences contained two verbs, in what we call a serial verb construction. • The original force of Wŏ bă Zhāng-sān dă le therefore was ‘I took Zhang-san [and] hit [him]’.

Shift of markedness and Reanalysis • This would have been a marked construction at first, but it came to be used increasingly in some circumstances, until today it is the unmarked form. • Alongside the markedness shift, there was a reanalysis: the verb bă, ‘take’, was bleached of its sense and reinterpreted as a mere grammatical marker of a following object, and the second verb dă, ‘hit’ was reinterpreted as the main (and only) verb in the sentence. • So the SOV construction has been extended to cases in which this older meaning would be inappropriate: • Zhāng-sān bă Lī-si pīping le Zhang -san Obj Li-si criticize Asp ‘Zhangsan criticized Li-si’

Grammaticalization • We saw in our discussion of morphologization that lexical items can be reduced to bound morphemes, but they can also be reduced to grammatical items without entirely losing their status as words in a process called grammaticalization. • The progressive form of the verb go has been available for centuries in constructions such as I am going home, in which go clearly retains its ordinary verbal sense. • This same construction could also be used with a complement of purpose, in cases like I am going to visit Miss Doris, in which the verb go still had its ordinary meaning. • The structure of such a sentence would be [I] [am going] [to visit Miss Doris], broadly parallel to [I] [am going] [home].

Grammaticalization • Such a sentence could be uttered by a speaker who was actually on her way to Miss Doris’s house, but equally, and crucially, it could be uttered by someone just about to set out, just like I’m going home. • As a consequence, speakers began to reanalyse such utterances as expressing, not actual motion, but rather an intention for the near future. • Accordingly, it became possible for something like I am going to buy a new carriage to be said by someone sitting comfortably at home with no immediate intention of moving. • The new usage has extended its domain very rapidly, and today we routinely say things like You’re going to like this book, in which no relevant motion is even conceivable.

Grammaticalization • Therefore, the be going to construction has entirely lost its original connection with movement and become a mere grammatical marker of the (near) future. Together with the grammaticalization, the structure has been reanalyzed. • We no longer have the old structure [I] [am going] [to buy a new car]; instead, we have [I] [am] [going to] [buy a new car], in which going to forms part of a single grammatical marker. • Observe that this new going to can now be reduced to gonna, as in I’m gonna buy a new car. The same is not possible with the ordinary progressive of the verb go, as in *I’m gonna home, in which going and to do not constitute parts of a single grammatical form.

Going to - overview • Utterances expressing actual motion I am going home I am going to visit Miss Doris (used with a complement) • Parallel Structures [I] [am going] [home] [I] [am going] [to visit Miss Doris] • Used in different contexts I am going to visit Miss Doris Speaker actually on his/her way to Miss Doris’s house I am going to visit Miss Doris Speaker about to set out on his/her way to Miss Doris’s house • Construction reanalysed as expressing, not actual motion, but an intention for the near future.

Going to - overview • Utterance expressing actual motion I am going home • Utterance expressing an intention for the near future I am going to visit Miss Doris I am going to buy a new carriage • Used in a newer contexts: I am going to buy a new carriage Speaker actually sitting at home with no intention of moving in the near future. • The new usage rapidly extends its domain You’re going to like this book You’re going to wish you were dead (when you hear the news) No relevant motion even conceivable.

Going to - overview • Original structure: utterance expressing actual motion: I am going home [I] [am going] [home] I am going to visit Miss Doris [I] [am going] [to visit Miss Doris] • Newer structure: utterance expressing a future: I am going to visit Miss Doris [I] [am] [going to] [visit Miss Doris] I am going to buy a new carriage [I] [am] [going to] [buy a new carriage] • Phonetic reduction in the newer construction [I] [am] [going to] [buy a new carriage] I’m gonna buy a new carriage *I’m gonna home

Grammaticalization • Grammaticalization of this type has been called bleaching, and such bleaching of lexical meaning is a very common source of grammatical items. • Another example from English is the verb will. It used to be a lexical verb meaning ‘want’, as in the Shakespearian form: What wilt thou? ‘What do you want? ’ • Today, however, it has been reduced entirely to a grammatical marker, also a kind of future marker: She will be home soon. • But note the interesting difference of meaning between: I’ll wash the dishes - an offer I’m going to wash the dishes - a statement.

Grammaticalization • Grammaticalization is not confined to operating within single sentences; it is quite possible for it to apply in such a way as to join two consecutive sentences into one. • Observe the usual manner of constructing complement clauses in the Germanic languages: • English: I believe that she will take the job. German: Ich verstehe daß Sie nicht kommen. (‘I understand that you’re not coming. ’) Dutch: Ik weet dat hij veel vrienden heft. (‘I know that he has a lot of friends. ’) • In all of these languages, the complement clause is introduced by a grammatical particle, a complementizer: that, daß, dat.

Grammaticalization • In the ancestral variety of the Germanic languages, the modern complement construction must not have existed. • Instead of using a single sentence with a subordinate clause, speakers used two separate sentences. • So, instead of saying: I believe that she will marry him, They said, literally, the following: She will marry him. I believe that. • The first process towards its systematization must have been a fixing of the word order to: I believe that. She will marry him.

Grammaticalization • Over time, however, this very frequent sequence underwent grammaticalization. The two sentences were combined into one: I believe that. She will marry him. I believe that she will marry him. • The demonstrative was reduced to a mere grammatical particle and then underwent phonological reduction: I believe [ðæt] that she will marry him. I believe [ðət] she will marry him.

Grammaticalization • The examples discussed illustrate the ordinary course of grammaticalization: • an ordinary lexical item with an ordinary meaning comes to be used in some particular context; • it is then bleached of its original meaning and becomes a mere grammatical marker in a syntactic construction; • finally it is reduced to a bound morpheme, an affix, a piece of morphology. • Naturally, there is no requirement that every slight tendency toward grammaticalization will go all the way, but, as a general rule, if anything happens at all, it will conform to this schema.