John keats The artist Ode on a Grecian

- Slides: 25

John keats The artist Ode on a Grecian Urn Text Analysis 1

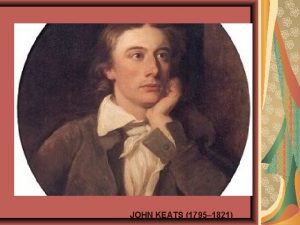

John Keats (1795 -1821) • Life and works • Productive Years (1817 -1821) • Illness and Death (1820 -1821) • The contradictions of art • Ode on a Grecian Urn Analysis 2

Life and works • • • John Keats was born near London on October 31 st, 1795. The first son of a stable-keeper, he had a sister and three brothers, one of whom died in infancy. When John was eight years old, his father was killed in an accident. In the same year his mother married again, but a little later separated from her husband took her family to live with her mother. John attended a good school where he became well acquainted with ancient and contemporary literature. In 1810 his mother died of consumption, leaving the children to their grandmother. The old lady put them under the care of two guardians, to whom she made over a respectable amount of money for the benefit of the orphans. Under the authority of the guardians, he was taken from school to be an apprentice to a surgeon. In 1814, before completion of his apprenticeship, John left his master after a quarrel, becoming a hospital student in London. Under the guidance of his friend Cowden Clarke he devoted himself increasingly to literature. In 1814 Keats finally sacrificed his medical ambitions to a literary life. He soon got acquainted with celebrated artists of his time, like Leigh Hunt, Percy B. Shelley and Benjamin Robert Haydon. 3

Productive Years (1817 -1821) • • • Keats travelled to the Isle of Wight on his own in spring of 1817. In the late summer he went to Oxford together with a newly-made friend, Benjamin Bailey. In the following winter, George Keats married and emigrated to America, leaving the consumptuous brother Tom in John's care. Apart from helping Tom against consumption, Keats worked on his poem "Endymion". Just before its publication, he went on a hiking tour to Scotland Ireland with his friend Charles Brown. First signs of his own fatal disease forced him to return prematurely, where he found his brother seriously ill and his poem harshly criticized. In December 1818 Tom Keats died. John moved to Hampstead Heath, were he lived in the house of Charles Brown. While in Scotland with Keats, Brown had lent his house to a Mrs Brawne and her sixteen-year-old daughter Fanny. Since the ladies were still living in London, Keats soon made their acquaintance and fell in love with the beautiful, fashionable girl. Absorbed in love and poetry, he exhausted himself mentally, and in autumn of 1819, he tried to gain some distance from literature through an ordinary occupation. 4

Illness and Death • • • An unmistakeable sign of consumption in February 1820 however broke all his plans for the future, marking the beginning of what he called his "posthumous life". He could not enjoy the positive resonance on the publication of the volume "Lamia, Isabella &c. ", including his most celebrated odes. In the late summer of 1820, Keats was ordered by his doctors to avoid the English winter and move to Italy. His friend Joseph Severn accompanied him south - first to Naples, and then to Rome. His health improved momentarily, only to collapse finally. Keats died in Rome on the 23 rd of February, 1821. He was buried in the Protestant Cemetery. On his desire, the following lines were engraved on his tombstone: "Here lies one whose name was writ in water. " 5

The contradictions of art • Keats’s ideal of beauty and art is very complex and contains many contradictions. • The figures on the urn are eternal, but there is a price to pay for eternity: • immobility and lack of vitality. • Indeed the figures on the urn have been “frozen” in a state of pure beauty – the girl will always be young and beautiful, the leaves will never fall from the tree etc. – but at the same time they are “ cold “, the people are made of marble. • Art therefore may be eternal but it also means death, and life does decay but at the same time can be enjoyed. • This central ambiguity of the artwork is an example of Keats’s notion of “negative capability” – the quality he thought essential to the poet. 6

The face of silence Ode on a Grecian Urn by John Keats Analysis II stanza IV stanza • I stanza THOU still unravish’d bride of quietness, Thou foster-child of silence and slow time, Sylvan historian, who canst thus express A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme: What leaf-fring’d legend haunts about thy shape Of deities or mortals, or of both, In Tempe or the dales of Arcady? What men or gods are these? What maidens loth? What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape? What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy? 7

Analysis I stanza • • • Summary In the first stanza, the speaker stands before an ancient Grecian urn and addresses it. He is preoccupied with its depiction of pictures frozen in time. It is the “still unravish’d bride of qiuetness, ” the “foster-child of silence and slow time. ” He also describes the urn as a “historian” that can tell a story. He wonders about the figures on the side of the urn and asks what legend they depict and from where they come. He looks at a picture that seems to depict a group of men pursuing a group of women and wonders what their story could be: “What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape? What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy? 8

Ode on a Grecian Urn • II stanza Analysis Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on; Not to the sensual ear, but, more endear’d, Pipe to the spirit ditties of no tone: Fair youth, beneath the trees, thou canst not leave Thy song, nor ever can those trees be bare; Bold Lover, never canst thou kiss, Though winning near the goal - yet, do not grieve; She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss, For ever wilt thou love, and she be fair! 9

Analysis II stanza • Here the speaker looks at another picture on the urn, this time of a young man playing a pipe, lying with his lover beneath a glade of trees. The speaker says that the piper’s “unheard” melodies are sweeter than mortal melodies because they are unaffected by time and they are the inspiration of our personal imagination – the romantic concept of the role of the artist – He tells the youth that, even though he can never kiss his lover because he is frozen in time, he should not grieve, because her beauty will never fade – eternal youth associated with eternal beauty. 10

home Ode on a Grecian Urn III stanza Analysis Ah, happy boughs! that cannot shed Your leaves, nor ever bid the Spring adieu; And, happy melodist, unwearied, For ever piping songs for ever new; More happy love! more happy, happy love! For ever warm and still to be enjoy’d, For ever panting, and for ever young; All breathing human passion far above, That leaves a heart high-sorrowful and cloy’d, A burning forehead, and a parching tongue. 11

Analysis III stanza • In this stanza, the poet looks at the trees surrounding the lovers and feels happy that they will never shed their leaves. He is happy for the piper because his songs will be “for ever new”, and happy that the love of the boy and girl will last forever, unlike mortal love – the immortality of art – which lapses into “breathing human passion” and eventually vanishes, leaving behind only a “burning forehead, and a parching tongue. ” 12

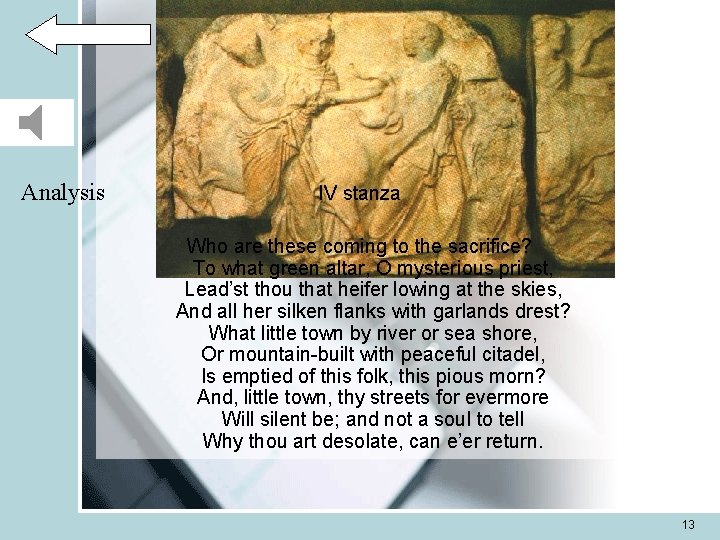

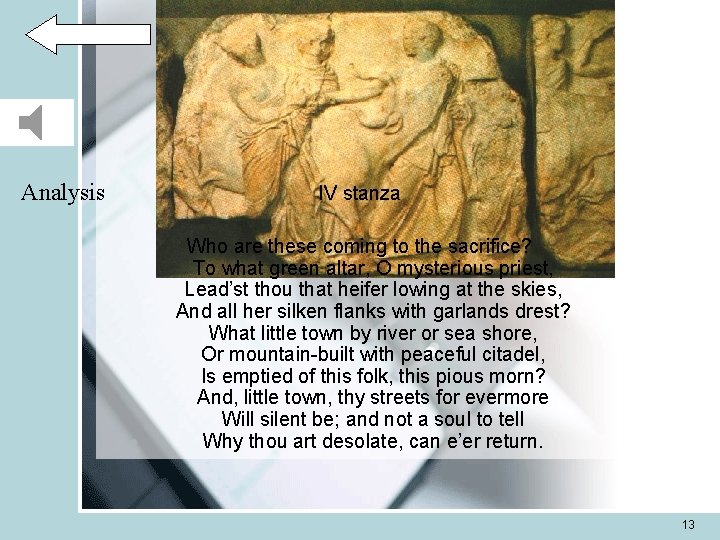

Analysis IV stanza Who are these coming to the sacrifice? To what green altar, O mysterious priest, Lead’st thou that heifer lowing at the skies, And all her silken flanks with garlands drest? What little town by river or sea shore, Or mountain-built with peaceful citadel, Is emptied of this folk, this pious morn? And, little town, thy streets for evermore Will silent be; and not a soul to tell Why thou art desolate, can e’er return. 13

home Analysis IV stanza • Here, the speaker examines another picture on the urn, this one of a group of villagers leading a heifer (young cow) to be sacrified. • He wonders where they are going “To what green altar, O mysterious priest…” and from where they have come. • He imagines their little town, empty of all its citizens, and tells it that its street will “ for evermore” be silent, for those who have left it, frozen on the urn, will never return. 14

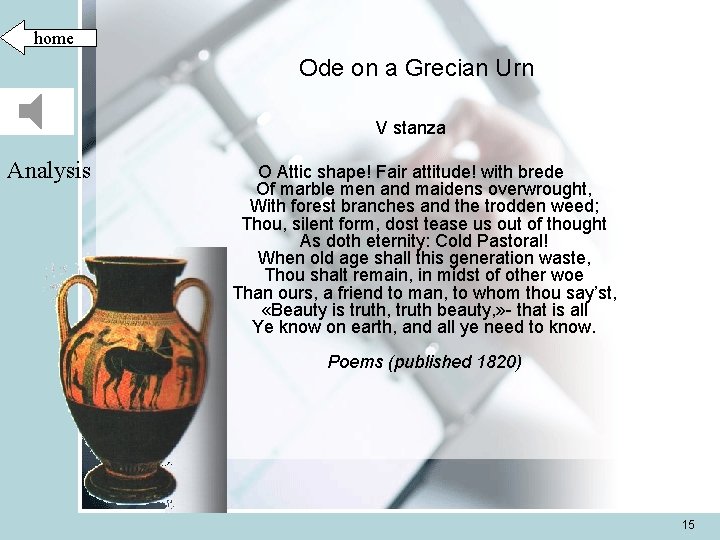

home Ode on a Grecian Urn V stanza Analysis O Attic shape! Fair attitude! with brede Of marble men and maidens overwrought, With forest branches and the trodden weed; Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thought As doth eternity: Cold Pastoral! When old age shall this generation waste, Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say’st, «Beauty is truth, truth beauty, » - that is all Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know. Poems (published 1820) 15

Analysis V stanza • In this final stanza, the speaker again addresses the urn itself, saying that it, like Eternity, “doth tease us out of thought. ” He thinks that when his generation is long dead, the urn will remain, telling future generations (thus, historian) its enigmatic lesson: Beauty is truth, truth beauty. ” The speaker says that is the only thing the urn knows and the only thing it needs to know. It also expresses the superiority of art over human passions. If human life is a succession of “hungry generations, “ as the speaker suggests in “Nightingale, ” the urn is a separate and self-contained world. ” It can be “a friend to man, ” as the speaker says, but it cannot be mortal; the kind of aesthetic connection the speaker experiences with the urn is ultimately insufficient to human life. END 16

Form • Each of the five stanzas in "Grecian Urn" is ten lines long, metered in a relatively precise iambic pentameter, and divided into a two part rhyme scheme, the last three lines of which are variable. 17

Form • In stanza one, lines seven through ten are rhymed DCE; • in stanza two, CED; • in stanzas three and four, CDE; • in stanza five, DCE, just as in stanza one. As in other odes (especially "Autumn" and "Melancholy"), the two-part rhyme scheme (the first part made of AB rhymes, the second of CDE rhymes) creates the sense of a two-part thematic structure as well. 18

Form • As in other odes (especially "Autumn" and "Melancholy"), the two-part rhyme scheme (the first part made of AB rhymes, the second of CDE rhymes) creates the sense of a two-part thematic structure as well. • The first four lines of each stanza roughly define the subject of the stanza, and the last six roughly explicate or develop it. 19

Themes • The Grecian urn, passed down through countless centuries to the time of the speaker's viewing, exists outside of time in the human sense • it does not age, it does not die, and indeed it is alien to all such concepts. • In the speaker's meditation, this creates an intriguing paradox for the human figures carved into the side of the urn: • They are free from time, but they are simultaneously frozen in time. • They do not have to confront aging and death (their love is "for ever young"), but neither can they have experience (the youth can never kiss the maiden; the figures in the procession can never return to their homes). 20

• The speaker attempts three times to engage with scenes carved into the urn; • each time he asks different questions of it. In the first stanza, he examines the picture of the "mad pursuit" and wonders what actual story lies behind the picture: • "What men or gods are these? What maidens loth? " • Of course, the urn can never tell him the whos, whats, whens, and wheres of the stories it depicts, and the speaker is forced to abandon this line of questioning. 21

• In the second and third stanzas, he examines the picture of the piper playing to his lover beneath the trees. • Here, the speaker tries to imagine what the experience of the figures on the urn must be like; he tries to identify with them. • He is tempted by their escape from temporality and attracted to the eternal newness of the piper's unheard song and the eternally unchanging beauty of his lover. • He thinks that their love is "far above" all transient human passion, which, in its sexual expression, inevitably leads to an abatement of intensity--when passion is satisfied, all that remains is a wearied physicality: a sorrowful heart, a "burning forehead, " and a "parching tongue. “ • His recollection of these conditions seems to remind the speaker that he is inescapably subject to them, and he abandons his attempt to identify with the figures on the urn. 22

• In the fourth stanza, the speaker attempts to think about the figures on the urn as though they were experiencing human time, imagining that their procession has an origin (the "little town") and a destination (the "green altar"). • But all he can think is that the town will forever be deserted: • If these people have left their origin, they will never return to it. • In this sense he confronts head-on the limits of static art; if it is impossible to learn from the urn the whos and wheres of the "real story" in the first stanza, it is impossible ever to know the origin and the destination of the figures on the urn in the fourth. 23

• In the final stanza, the speaker presents the conclusions drawn from his attempts to engage with the urn. • His idle curiosity in the first attempt gives way to a more deeply felt identification in the second, and in the third, the speaker leaves his own concerns behind and thinks of the processional purely on its own terms, thinking of the "little town" with a real and generous feeling • He is overwhelmed by its existence outside of temporal change, with its ability to "tease" him "out of thought / As doth eternity. “ • If human life is a succession of "hungry generations, " as the speaker suggests in "Nightingale, " the urn is a separate and self-contained world. • It can be a "friend to man, " as the speaker says, but it cannot be mortal; the kind of aesthetic connection the speaker experiences with the urn is ultimately insufficient to human life. 24

Themes • The final two lines, in which the speaker imagines the urn speaking its message to mankind • "Beauty is truth, truth beauty, " have proved among the most difficult to interpret in the Keats canon. • After the urn utters the enigmatic phrase "Beauty is truth, truth beauty, " no one can say for sure who "speaks" the conclusion, "that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know. “ • It could be the speaker addressing the urn, and it could be the urn addressing mankind 25

Ode to a nightingale summary stanza by stanza

Ode to a nightingale summary stanza by stanza Ode on a grecian urn quiz

Ode on a grecian urn quiz Ode on a grecian urn paraphrase

Ode on a grecian urn paraphrase Ode on a grecian urn summary

Ode on a grecian urn summary Whats and ode

Whats and ode On the grasshopper and the cricket literary devices

On the grasshopper and the cricket literary devices I cannot exist without you john keats

I cannot exist without you john keats She dwells with beauty beauty that must die

She dwells with beauty beauty that must die Poem summary

Poem summary Ode to nightingale quiz

Ode to nightingale quiz John keats 1819

John keats 1819 Dead poets society

Dead poets society The earliest known grecian epics were written by____ .

The earliest known grecian epics were written by____ . Who are the grecians

Who are the grecians Keats elegy

Keats elegy Natalie kon-yu

Natalie kon-yu On seeing the elgin marbles

On seeing the elgin marbles Keats kings

Keats kings Keats byron shelley

Keats byron shelley Lois lowry drawing

Lois lowry drawing Ng-html

Ng-html đặc điểm cơ thể của người tối cổ

đặc điểm cơ thể của người tối cổ Sơ đồ cơ thể người

Sơ đồ cơ thể người Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

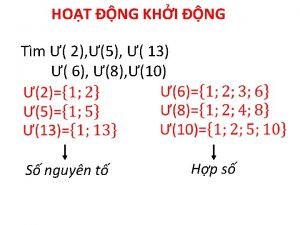

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Số nguyên tố là gì

Số nguyên tố là gì Tư thế worm breton

Tư thế worm breton