International Considerations in Licensing Karl F Jorda David

- Slides: 26

International Considerations in Licensing Karl F. Jorda David Rines Professor of IP Law & Industrial Innovation Director, Kenneth J. Germeshausen Center for the Law of Innovation & Entrepreneurship Franklin Pierce Law Center Two White Street, Concord, NH 03301 Seminar Siam Cement Group Bangkok, Thailand December 19 -20, 2006

I. International Considerations in Licensing a) Importance of Licensing The growth in importance of international licensing to the US economy is unmistakable. Between 1950 and 1980, US companies signed approximately 32, 000 licensing agreements. In the 1990 s, licensing grew at an unprecedented pace with the advent of technological developments in computer technology, biotechnology and pharmaceuticals. The incentives to licensing are obvious: companies from less developed countries want to duplicate their more developed counterparts’ successes and are eager to offer lower cost production alternatives and companies in more developed countries seek new ides and new markets in which to exploit their existing intellectual property assets. The rules governing the transfer of technology have been evolving for decades and will continue changing as the importance of licensing increases. The governments of many countries recognize the growth of international licensing and have worked to lower the barriers and ease the systematic impediments of importing and exporting technology. 2

b) Cultural and Legal Differences • Variances in legal systems and cultures still can make international licensing difficult at best and a potential trap for the unwary. • All of the issues surrounding domestic licensing remain but the international license brings complexities of dealing in more than one legal system, international law, governmental regulation, and different business and cultural practices. • Moreover, hidden differences, special issues and unique syndromes abound in the agreement negotiation and drafting stages • Two general categories of differences: – Culture and language – Different legal systems • Cultural differences in particular are the greatest stumbling blocks, especially I the negotiation phase. 3

II. Cultural Differences a) Hidden Differences/Unique Syndromes Three uniquely Japanese syndromes: • Black Ships Syndrome The expression “Black ships have arrived again” recalls Commodore Perry’s black ship in Tokyo harbor in 1854 and indicates exertion of pressure from the outside, e. g. • IBM’s move to Tokyo in 1984 • PIPA delegation in Tokyo in 1984: “Gray Ships” Best to use low-key approach • Totem Pole Syndrome Vestiges of caste system - authority and title are greatly valued Government officials, e. g. , MITI officials and JPO examiners higher than lawyers and IP practitioners The latter can’t be aggressive Must help them help you 4

a) Hidden Differences/Unique Syndromes (cont’d) • • Black Hole Syndrome Tadao Umesao: In terms of communications Japan is like a Black Hole: It receives but does not emit signals. Getting information has a positive social value while giving it is considered harmful. • Reluctance to “open the kimono” • Resistance to auditing provisions • Avoidance of definite commitments even in negotiations • Ties in with “Silence is gold, eloquence is silver” • Don’t “feel any need to reveal what (they) know. • Are “glad to sit and listen. ” • With patience they “usually learn what (they) want to know. ” (See my article on “Patent Solicitation and Licensing in Japan”) 5

b) Negotiations • Preliminary negotiations are more important in the Far East than in the US. • Americans have a direct let’s get-down-to-business negotiation style. • In many other countries, establishing a social relationship comes first. • A personal relationship (“Guan Xi”) of mutual trust and respect. • Parties need to be able to have “heart-to-heart” (indirect) communications. • Americans can conduct business with people they don’t know or can’t stand —“it’s just business. ” Elsewhere, if they don’t know or like you, they won’t do business with you. • Culture clashes can derail overseas deals — and quickly. • E. g. US Chief IP Counsel leaves Tokyo in a huff at the end of a week of negotiations because “nothing had happened. ” In fact, he also told me he had insisted they “had to do it his way. ” 6

b) Negotiations (cont’d) Other true (apocryphal? ) stories: • American negotiation team getting frustrated after ten days of “dilly-dallying” by Japanese and leave at point when Japanese were ready to wrap up deal • Another American negotiation team getting impatient already on first day (Monday) because of delegation small talk — delegation head pounds table and protests: “Let’s get down to business. We have a plane to catch on Friday. ” (Time is money. ) • Three tractor salesmen go to Japan to sell tractors. Make a great presentation with pricing. No reaction from Japanese. Americans get nervous and lower price. Still no reaction from the Japanese. Americans again lower price way beyond plan. • Silence of Japanese due to need to think about it and build consensus. • Patience is key — even in excruciating periods of silence. • Americans: Japanese approach to business negotiations wastes time to business deals. • Japanese complain about the dry American Attitude to business deals 7

b) Negotiations (cont’d) • The extended preliminary socialization of about a week or more should actually be welcome to American negotiators — it can also help in understanding the mindset of potential licensing partner. • In this connection, it is helpful to bone up not only on the legal system of the foreign country but also its geography and history and its economic and political system, thereby showing a genuine interest and understanding. • Also be aware of differences between monochronic (time schedules are important) and polychronic cultures (human relationships are important). 8

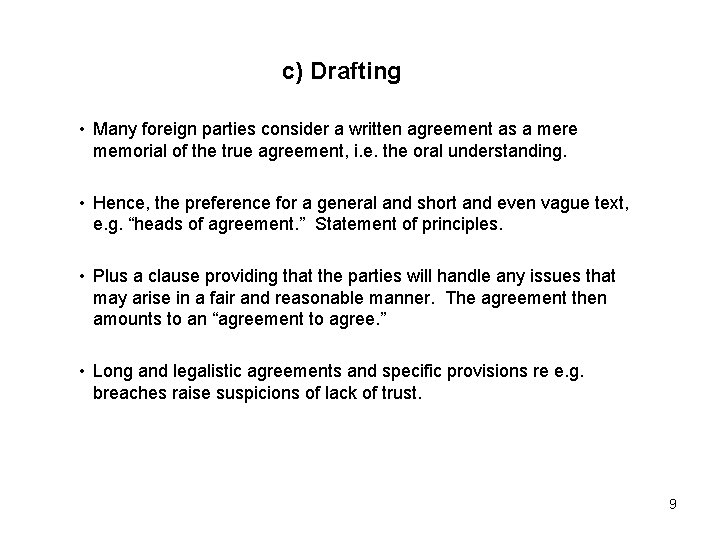

c) Drafting • Many foreign parties consider a written agreement as a mere memorial of the true agreement, i. e. the oral understanding. • Hence, the preference for a general and short and even vague text, e. g. “heads of agreement. ” Statement of principles. • Plus a clause providing that the parties will handle any issues that may arise in a fair and reasonable manner. The agreement then amounts to an “agreement to agree. ” • Long and legalistic agreements and specific provisions re e. g. breaches raise suspicions of lack of trust. 9

c) Drafting (cont’d) • Because of the need of brevity, the focus should be on the most important clauses, i. e. : –grant clause –definitions clause –termination clause –royalties • Sometimes Japanese may agree to a detailed written contract because of the need to file agreements with foreigners with JPO and/or FTC and also because of the American parol evidence rule. Great reluctance to do so. 10

c) Drafting (cont’d) • Example of a clause that the parties will deal with issues that may arise in a fair and reasonable manner. • Article 00 The parties shall discuss and decide in good faith the detailed matters necessary to perform this Agreement or the matters not provided in this Agreement. If a significant change in the business circumstances arises, the parties shall negotiate to change the terms and conditions of this Agreement to conform to such a change and the benefit of the parties. 11

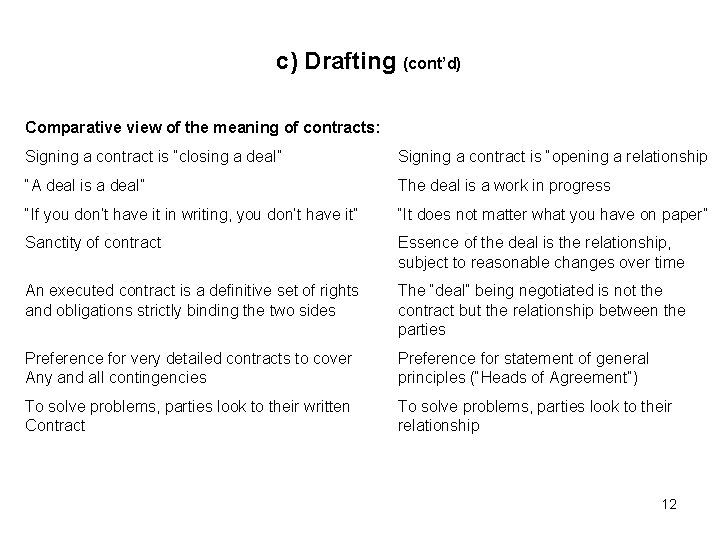

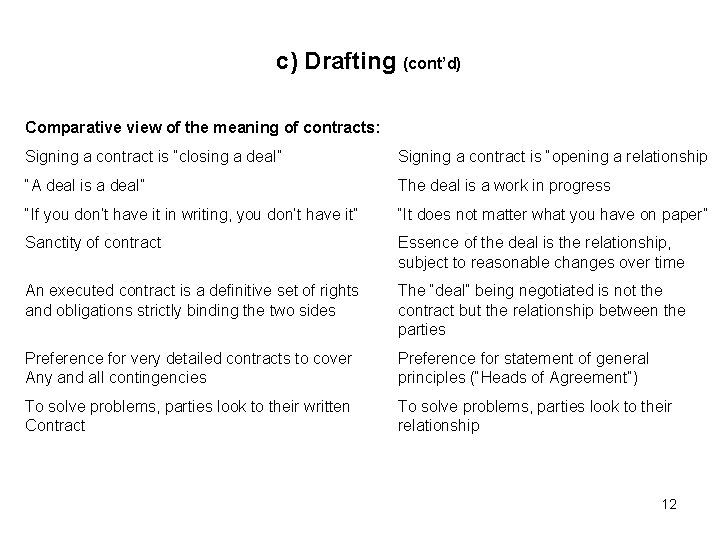

c) Drafting (cont’d) Comparative view of the meaning of contracts: Signing a contract is “closing a deal” Signing a contract is “opening a relationship “A deal is a deal” The deal is a work in progress “If you don’t have it in writing, you don’t have it” “It does not matter what you have on paper” Sanctity of contract Essence of the deal is the relationship, subject to reasonable changes over time An executed contract is a definitive set of rights and obligations strictly binding the two sides The “deal” being negotiated is not the contract but the relationship between the parties Preference for very detailed contracts to cover Any and all contingencies Preference for statement of general principles (“Heads of Agreement”) To solve problems, parties look to their written Contract To solve problems, parties look to their relationship 12

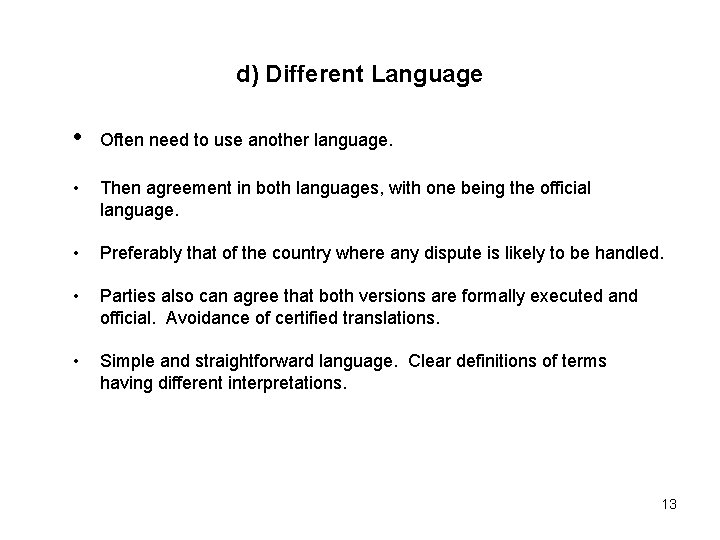

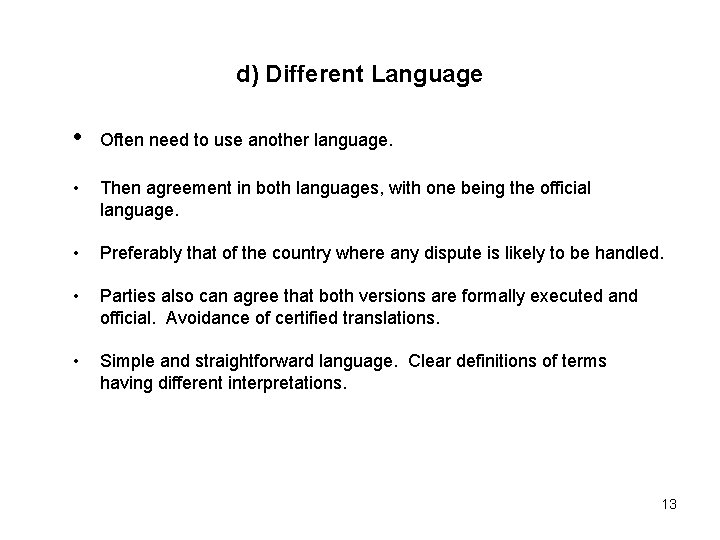

d) Different Language • Often need to use another language. • Then agreement in both languages, with one being the official language. • Preferably that of the country where any dispute is likely to be handled. • Parties also can agree that both versions are formally executed and official. Avoidance of certified translations. • Simple and straightforward language. Clear definitions of terms having different interpretations. 13

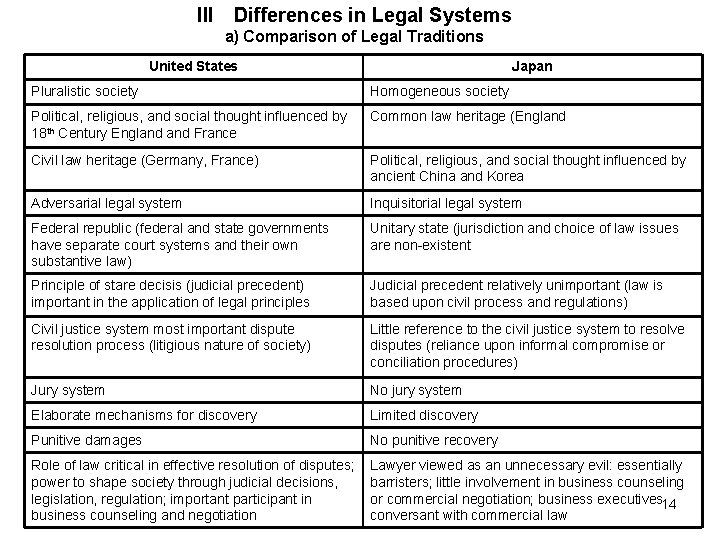

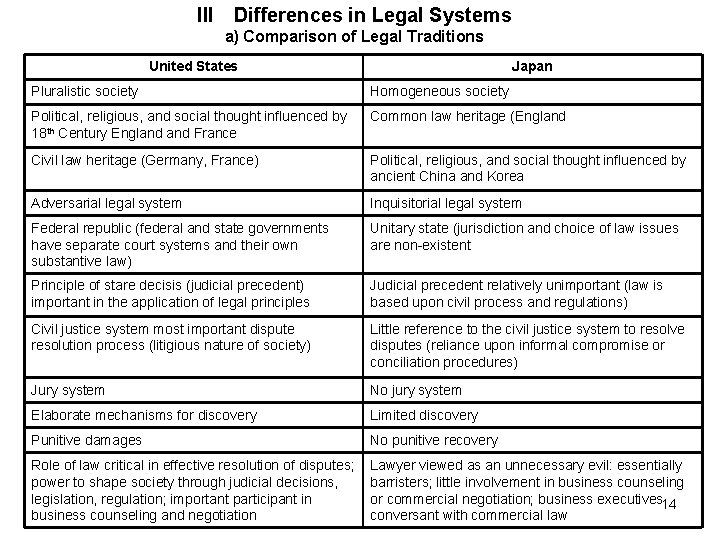

III Differences in Legal Systems a) Comparison of Legal Traditions United States Japan Pluralistic society Homogeneous society Political, religious, and social thought influenced by 18 th Century England France Common law heritage (England Civil law heritage (Germany, France) Political, religious, and social thought influenced by ancient China and Korea Adversarial legal system Inquisitorial legal system Federal republic (federal and state governments have separate court systems and their own substantive law) Unitary state (jurisdiction and choice of law issues are non-existent Principle of stare decisis (judicial precedent) important in the application of legal principles Judicial precedent relatively unimportant (law is based upon civil process and regulations) Civil justice system most important dispute resolution process (litigious nature of society) Little reference to the civil justice system to resolve disputes (reliance upon informal compromise or conciliation procedures) Jury system No jury system Elaborate mechanisms for discovery Limited discovery Punitive damages No punitive recovery Role of law critical in effective resolution of disputes; power to shape society through judicial decisions, legislation, regulation; important participant in business counseling and negotiation Lawyer viewed as an unnecessary evil: essentially barristers; little involvement in business counseling or commercial negotiation; business executives 14 conversant with commercial law

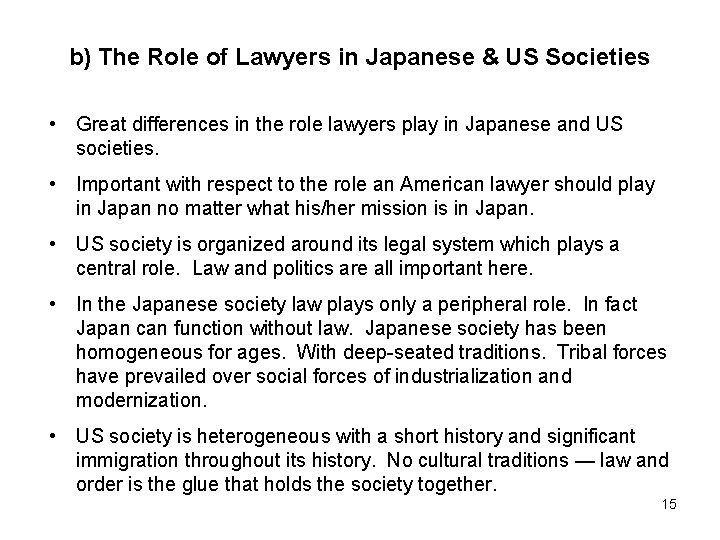

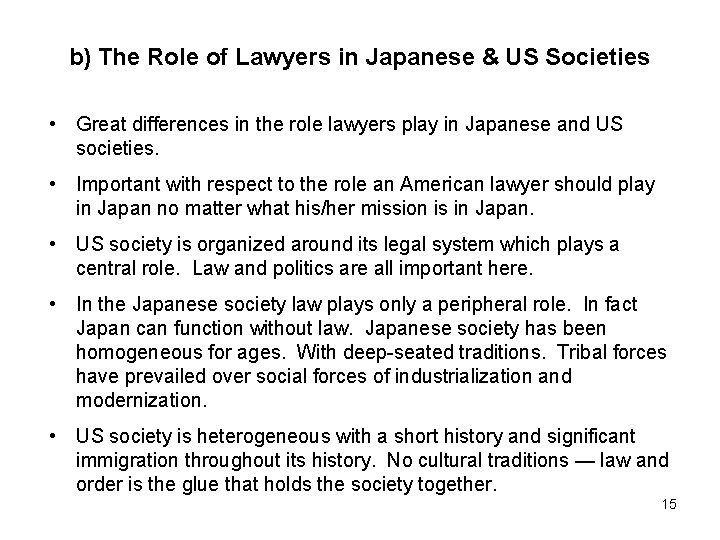

b) The Role of Lawyers in Japanese & US Societies • Great differences in the role lawyers play in Japanese and US societies. • Important with respect to the role an American lawyer should play in Japan no matter what his/her mission is in Japan. • US society is organized around its legal system which plays a central role. Law and politics are all important here. • In the Japanese society law plays only a peripheral role. In fact Japan can function without law. Japanese society has been homogeneous for ages. With deep-seated traditions. Tribal forces have prevailed over social forces of industrialization and modernization. • US society is heterogeneous with a short history and significant immigration throughout its history. No cultural traditions — law and order is the glue that holds the society together. 15

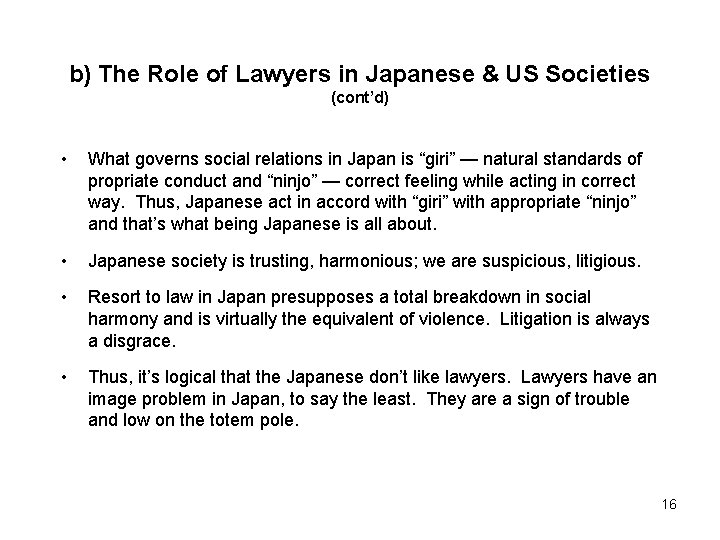

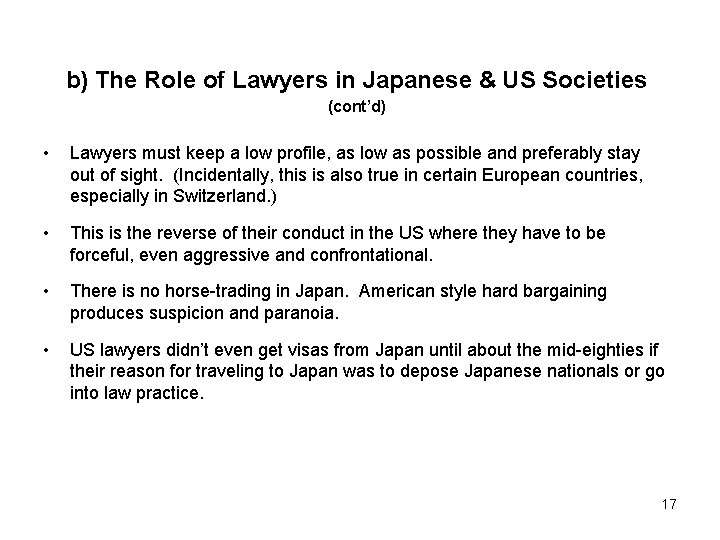

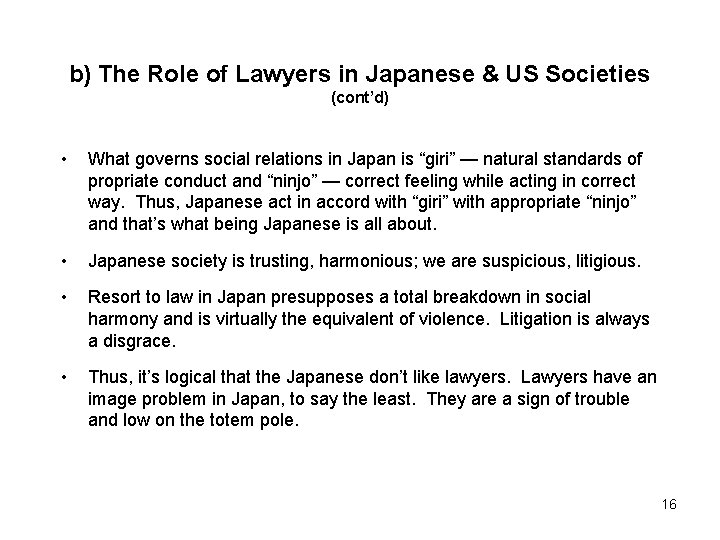

b) The Role of Lawyers in Japanese & US Societies (cont’d) • What governs social relations in Japan is “giri” — natural standards of propriate conduct and “ninjo” — correct feeling while acting in correct way. Thus, Japanese act in accord with “giri” with appropriate “ninjo” and that’s what being Japanese is all about. • Japanese society is trusting, harmonious; we are suspicious, litigious. • Resort to law in Japan presupposes a total breakdown in social harmony and is virtually the equivalent of violence. Litigation is always a disgrace. • Thus, it’s logical that the Japanese don’t like lawyers. Lawyers have an image problem in Japan, to say the least. They are a sign of trouble and low on the totem pole. 16

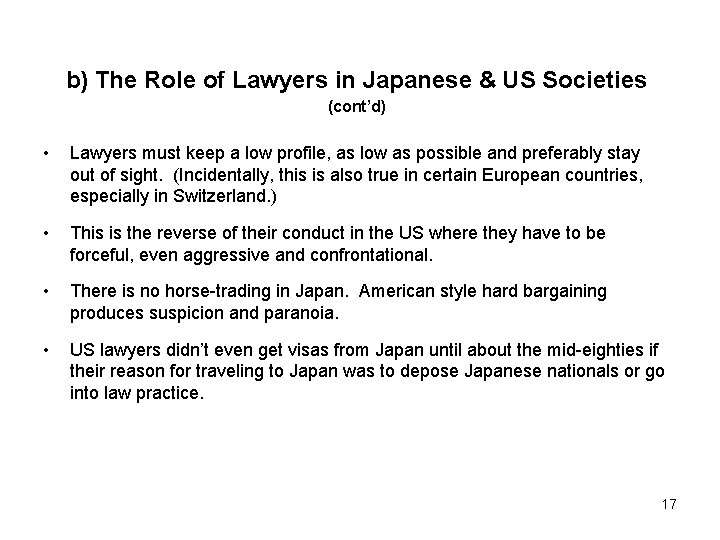

b) The Role of Lawyers in Japanese & US Societies (cont’d) • Lawyers must keep a low profile, as low as possible and preferably stay out of sight. (Incidentally, this is also true in certain European countries, especially in Switzerland. ) • This is the reverse of their conduct in the US where they have to be forceful, even aggressive and confrontational. • There is no horse-trading in Japan. American style hard bargaining produces suspicion and paranoia. • US lawyers didn’t even get visas from Japan until about the mid-eighties if their reason for traveling to Japan was to depose Japanese nationals or go into law practice. 17

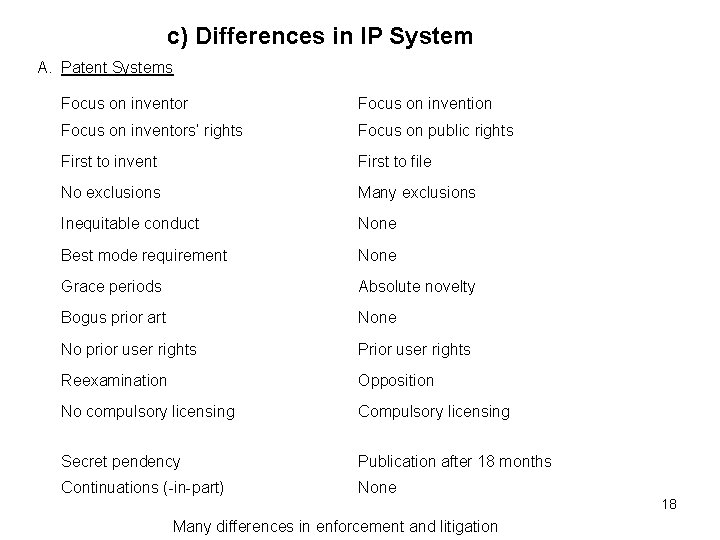

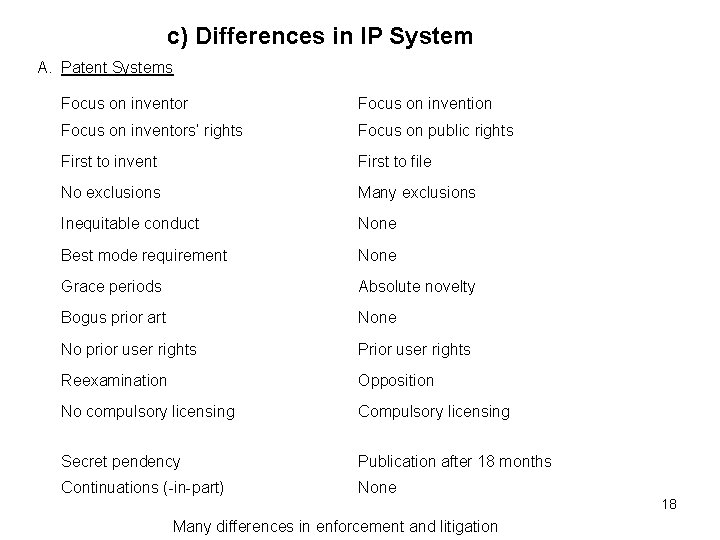

c) Differences in IP System A. Patent Systems Focus on inventor Focus on invention Focus on inventors’ rights Focus on public rights First to invent First to file No exclusions Many exclusions Inequitable conduct None Best mode requirement None Grace periods Absolute novelty Bogus prior art None No prior user rights Prior user rights Reexamination Opposition No compulsory licensing Compulsory licensing Secret pendency Publication after 18 months Continuations (-in-part) None Many differences in enforcement and litigation 18

c) Differences in IP System (cont’d) B. Trademark Systems Emphasis on use No “famous marks” (Dilution) Emphasis on registration Famous marks C. Copyright Systems Emphasis on work Weak moral rights Emphasis on author Strong moral rights D. Other Differences Multiple protection No utility models Single protection Utility models 19

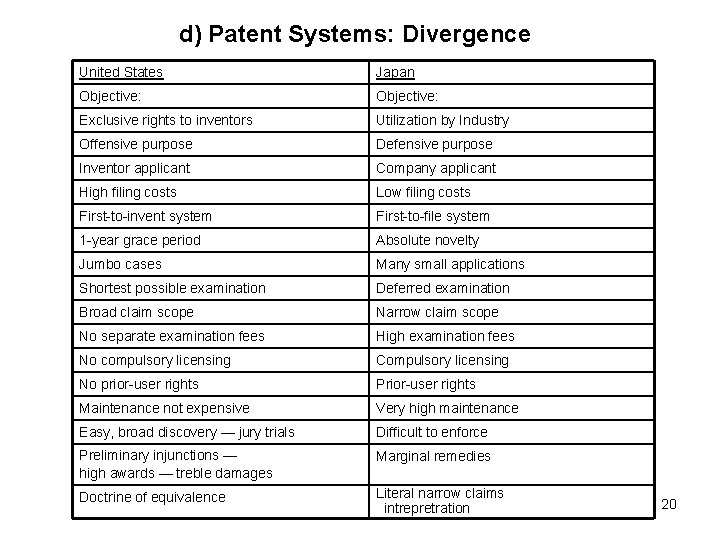

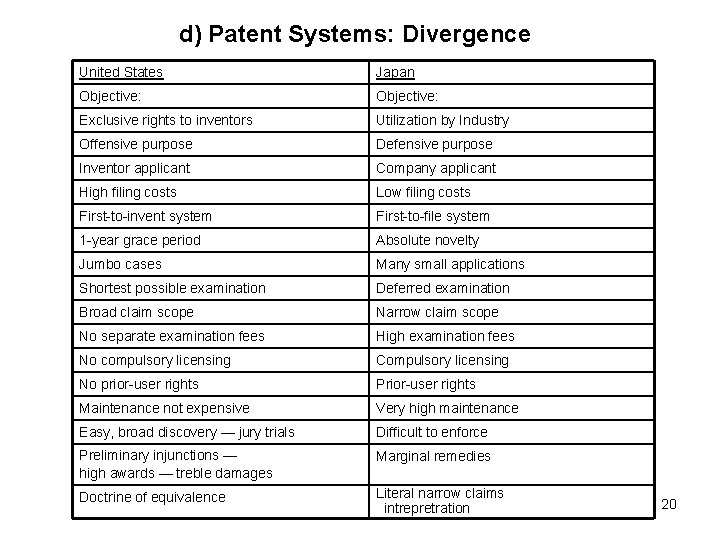

d) Patent Systems: Divergence United States Japan Objective: Exclusive rights to inventors Utilization by Industry Offensive purpose Defensive purpose Inventor applicant Company applicant High filing costs Low filing costs First-to-invent system First-to-file system 1 -year grace period Absolute novelty Jumbo cases Many small applications Shortest possible examination Deferred examination Broad claim scope Narrow claim scope No separate examination fees High examination fees No compulsory licensing Compulsory licensing No prior-user rights Prior-user rights Maintenance not expensive Very high maintenance Easy, broad discovery — jury trials Difficult to enforce Preliminary injunctions — high awards — treble damages Marginal remedies Doctrine of equivalence Literal narrow claims intrepretration 20

e) Additional Considerations • Format and terms of an international license may track a corresponding US license in many respects. • But competition laws, customs laws, employment law, tax laws loom larger in international licenses. • And special considerations and issues in foreign countries may come into play, such as governmental approvals, registration or recordation, applicable language, choice of applicable law, export regulations, arbitration, tax allocation and currency, etc. • Conversely, certain provisions the licensors routinely include in domestic license may not be enforceable abroad, as for example: – non-competition covenants – territorial restrictions, etc. 21

f) Competition (Antitrust) Laws Well developed antitrust now exist abroad. Their applicability needs to be considered as well as US antitrust laws if an international agreement would affect US commerce. Two general regimes have existed: a) “Ten commandments” approach Lists of white, gray, black license restrictions Prior approval requisite, unless “block exemptions” apply China, European Union, Japan, Latin countries, South Africa b) “Rule of Reason” approach No submission for approval Scrutiny or attack later, if (likely) adverse effect on competition Australia, Germany, UK, US Due to frequent revisions and complexities consultation with local counsel is essential. 22

IV. Conclusion In licensing in Japan as well as in China and Korea and other foreign countries, your objective should not be to drive a hard bargain and write tighter legalistic agreements, but rather to establish better personal and business relationships. 23

REACH OF U. S. ANTITRUST LAW “The Tokyo Disconnection” 1. 2. 3. 4. Japanese fax paper manufacturers meeting in Japan in 1990 agreed to fix prices. Manufacturers sold paper to Japanese trading houses for specific U. S. customers on the condition that they charge set prices. Paper makers monitored the trading houses to ensure that fixed prices were charged. The Justice Department asked the Japanese government in 1994 to help get price-fixing evidence in Japan. 24

REACH OF U. S. ANTITRUST LAW (continued) “The Tokyo Disconnection” (continued) 5. 6. 7. 8. The Japanese Prosecutor’s Office raided the Tokyo headquarters of two Japanese companies, seized documents for the Justice Department and later questioned company representatives in front of Justice officials. From 1994 through 1996, the U. S. government obtained indictments and guilty pleas from Japanese companies on criminal price-fixing charges under the Sherman Act. The 1 st U. S. Circuit Court of Appeals held in March 1997 that the Sherman Act can be used against foreign companies and citizens for conduct that occurred outside the United States. 25 The Sherman Act had gone abroad.

Thank you! Karl F. Jorda David Rines Professor of IP Law and Industrial Innovation Director, Kenneth J. Germeshausen Center for the Law of Innovation and Entrepreneurship Franklin Pierce Law, Concord, NH, USA 26

Jorda diameter

Jorda diameter Energibalansen i atmosfæren

Energibalansen i atmosfæren What are the general considerations in machine design?

What are the general considerations in machine design? Tax considerations for setting up a new business

Tax considerations for setting up a new business Software architecture of atm machine

Software architecture of atm machine Exchange transaction and relationship in marketing

Exchange transaction and relationship in marketing Mechanical design of transmission line

Mechanical design of transmission line Database design considerations

Database design considerations Compare and contrast first and second language acquisition

Compare and contrast first and second language acquisition What is cloud delivery model

What is cloud delivery model Writing strategies and ethical considerations

Writing strategies and ethical considerations Pre analytical considerations in phlebotomy

Pre analytical considerations in phlebotomy Bioreactor considerations for animal cell culture

Bioreactor considerations for animal cell culture Collaboration design considerations

Collaboration design considerations Principles of tooth preparation in fpd

Principles of tooth preparation in fpd Anatomical considerations

Anatomical considerations Biopharmaceutic considerations in drug product design

Biopharmaceutic considerations in drug product design Retromylohyoid curtain muscles

Retromylohyoid curtain muscles Dogso i spa

Dogso i spa Design considerations icons

Design considerations icons Acclimatisation pdhpe

Acclimatisation pdhpe Natalya hasan

Natalya hasan Experimental design and ethical considerations

Experimental design and ethical considerations Identify the device

Identify the device Design considerations for mobile computing

Design considerations for mobile computing Sample of appendices in research paper

Sample of appendices in research paper Non rebreather mask nursing considerations

Non rebreather mask nursing considerations