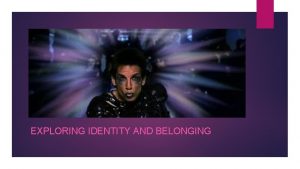

Identity economics meets identity leadership Exploring the consequences

![Study 1: Design Measures • • Leader pay manipulation check (“[This leader] is one Study 1: Design Measures • • Leader pay manipulation check (“[This leader] is one](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/5732c1c4badcbc6e299cf8e1a3c436bf/image-10.jpg)

- Slides: 19

Identity economics meets identity leadership: Exploring the consequences of CEO pay Nik Steffens Alex Haslam, Kim Peters, John Quiggin The University of Queensland 41 st ISPP Annual Scientific Meeting, 2018, San Antonio

Identity economics and organisational behavior • Identity economics departs from traditional economic models in arguing that people’s economic choices are not simply a function of the personal utility of those choices, but also derive from their group memberships (Akerlof & Kranton, 2010; Bénaubou & Tirole, 2011; Zehnder et al. , 2017) • • • Value derives from what is consistent with ‘who we are’ (Bénaubou & Tirole, 2011) This has implications for organizational behavior “Identity economics suggests that a firm operates well when employees identify with it and when their norms advance its goals. Because firms and other organizations are the backbone of all economies, this new description transforms our understanding of what makes economies work or fail. ” (Akerlof & Kranton, 2010, p. 15)

Identity leadership and organisational behavior • Identity leadership theorizing rests on the social identity approach (Tajfel & Turner, 1979; Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987) • • It is different from other leadership theories by arguing that leadership is a collective group-based social influence process Leaders are effective in influencing others to the extent that they create, represent, advance, and embed a shared sense of ‘we’ and ‘us’ in the group they lead (Haslam, Reicher, & Platow, 2011; Steffens et al. , 2014; van Dick et al. , 2018) • Charisma is not an input but an output resulting from leaders representing ‘who we are’ (Platow, van Knippenberg, Haslam, van Knippenberg, & Haslam, 2006; Steffens, Haslam, & Reicher, 2014)

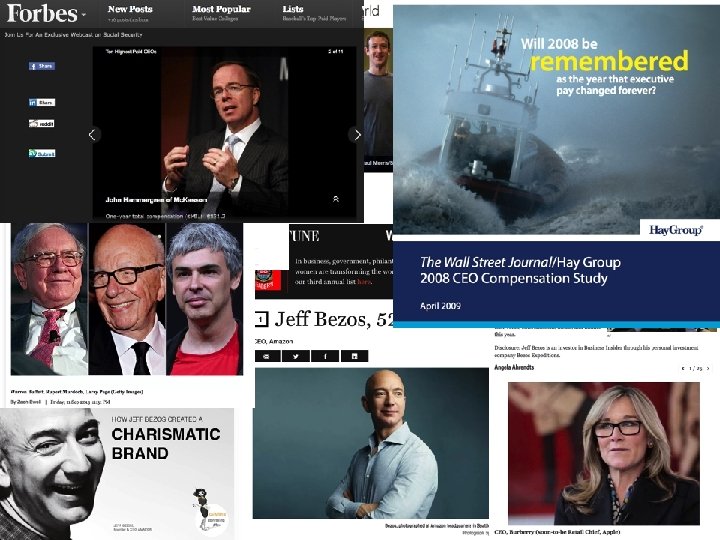

Applying identity leadership and identity economics: Understanding consequences of CEO pay • CEO pay has increased substantially in recent decades • Since the 1970 s in US major corporations: 600% to 1000% (Gabaix & Landier, 2008; Mishel & Davis, 2015) • While real wages of most workers have stagnated • Since 70 s they increased by 11% and since 2000 fell by 3. 7% (Desilver, 2014; Mishel & Davis, 2015) • • Increase in CEO pay contrasts with decelerating productivity growth since 70 s but has developed in parallel with increasing corporate profits and market valuation (Gabaix & Landier, 2008; Sprague, 2017)

What impact has CEO pay on their leadership? Standard economic models suggest that elevated incentives promote leadership • Incentive literature: • high incentives motivate leaders to do their jobs well and retain them (Gabaix & Landier, 2008; Pekala, 2001; Rynes, Gerhart, & Minette, 2004) • high incentives create aspirations and motivate others do their jobs well (Baker, Jensen, & Murphy, 1988; Latham & Locke, 1991) • • Shareholder value model: incentives motivate CEOs to maximize profit for shareholders by extracting greatest possible benefit Psychological & management literature: high incentives act as cues that signal that CEOs are charismatic and effective leaders (Rush, Thomas, & Lord, 1977; Moody, 2005)

What impact has CEO pay on their leadership? Identity economics & identity leadership suggest elevated incentives undermine leadership • Workers who identify with their leader are more likely to identify with the organization and exert effort on the behalf of the organization (Sluss et al. , 2012; Steffens et al. , 2014; van Dick et al. , 2007; Wieseke et al. , 2009) • • Elevated CEO pay creates ’us-versus-them’ dynamics and makes leaders be seen as selfinterested ‘outsiders’, reducing followers’ personal identification with leaders (H 1) This in turn undermines perceptions of their identity leadership and charisma (H 2) We conducted two studies to examine these questions Ø In both studies we assess and control for social dominance orientation (Pratto et al. , 1994) and meritocracy beliefs (Son Hing, 2011)

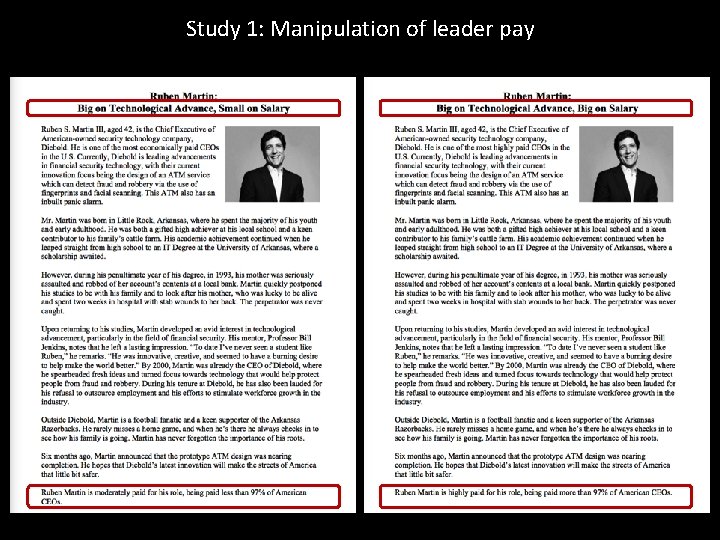

Study 1: Design Participants and Design • 590 US participants recruited via Amazon’s MTurk • Participants were randomly assigned to one of two experimental conditions: • a CEO who was (a) low-paid vs. (b) high-paid relative to other CEOs in the US

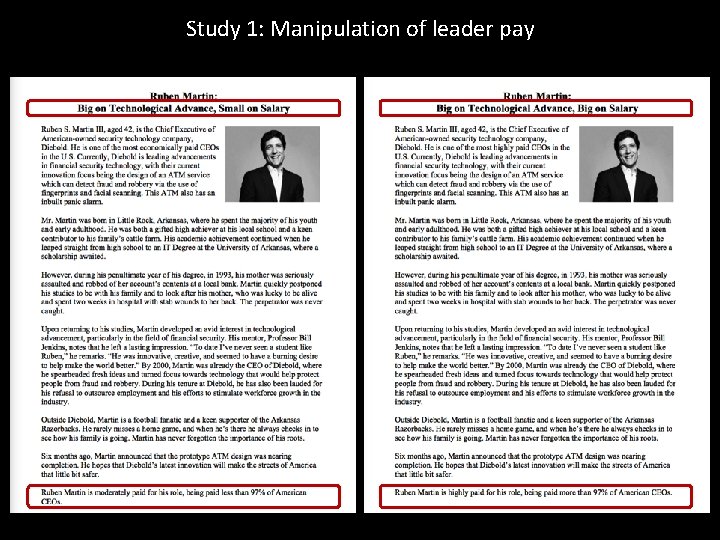

Study 1: Manipulation of leader pay

![Study 1 Design Measures Leader pay manipulation check This leader is one Study 1: Design Measures • • Leader pay manipulation check (“[This leader] is one](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/5732c1c4badcbc6e299cf8e1a3c436bf/image-10.jpg)

Study 1: Design Measures • • Leader pay manipulation check (“[This leader] is one of the top-paid CEOs in the US”) Personal identification with leader (4 items from Doosje et al. , 1995; “I identify with [this leader]”; ”I feel strong ties with [this leader]”) • Identity leadership (4 items from Steffens et al. 2014; “[This leader] is a model member of [the organization]”; “[This leader] acts as a champion for [the organization]”) • Leader charisma (8 items from Platow et al. , 2006; “[This leader] has a compelling vision for the future”; “[This leader] has a sense of mission”) Control variables • Social dominance orientation (16 items from Pratto et al. , 1994; “In getting what you want, it is sometimes necessary to use force against other groups”) • Meritocracy beliefs (15 items from Son Hing et al. , 2011; “In organizations, people who do their job well rise to the top”)

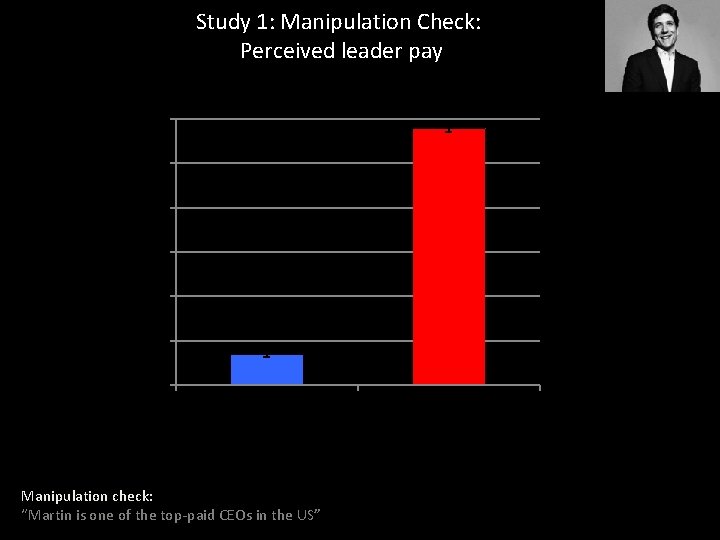

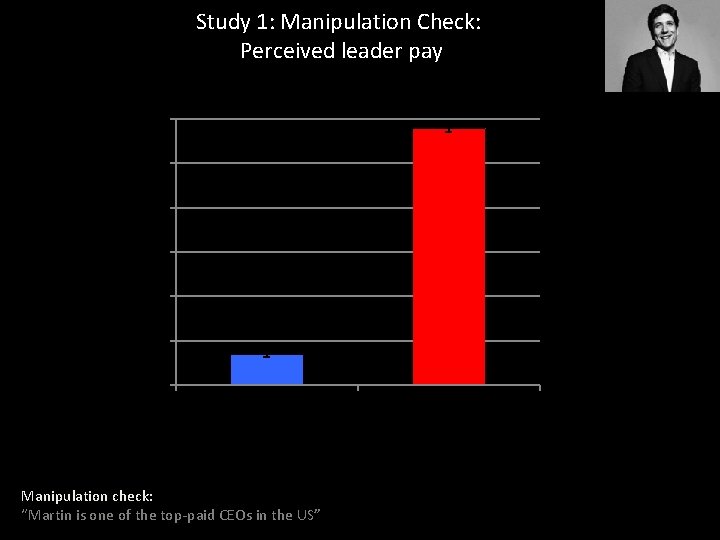

Study 1: Manipulation Check: Perceived leader pay 7 Perceived Leader Pay 6 5 4 3 2 1 Low-paid Leader High-paid Leader Experimental Condition Manipulation check: “Martin is one of the top-paid CEOs in the US”

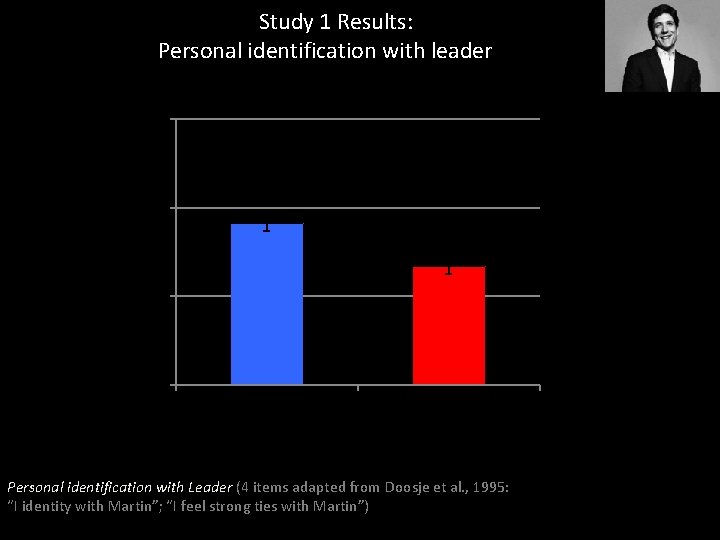

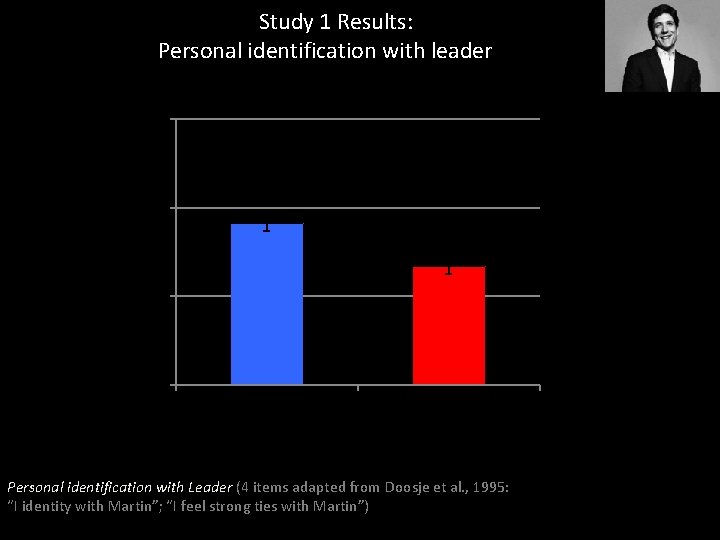

Study 1 Results: Personal identification with leader Personal Identification with Leader 5. 5 4. 5 3. 5 2. 5 Low-paid Leader High-paid Leader Experimental Condition Personal identification with Leader (4 items adapted from Doosje et al. , 1995: “I identity with Martin”; “I feel strong ties with Martin”)

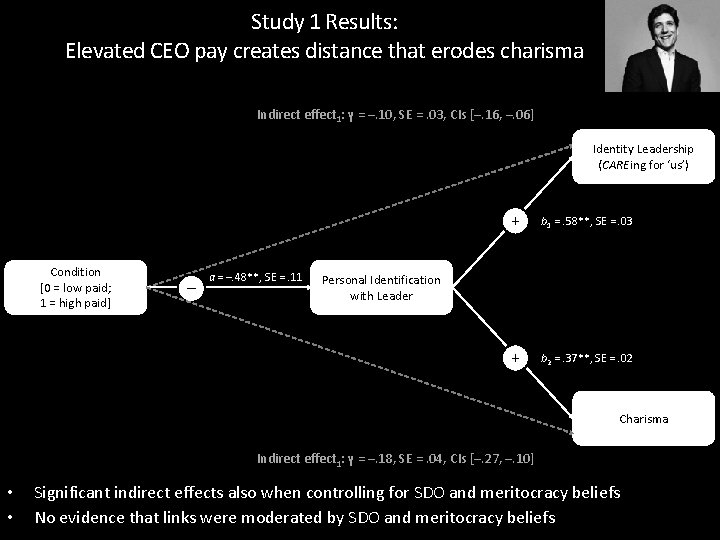

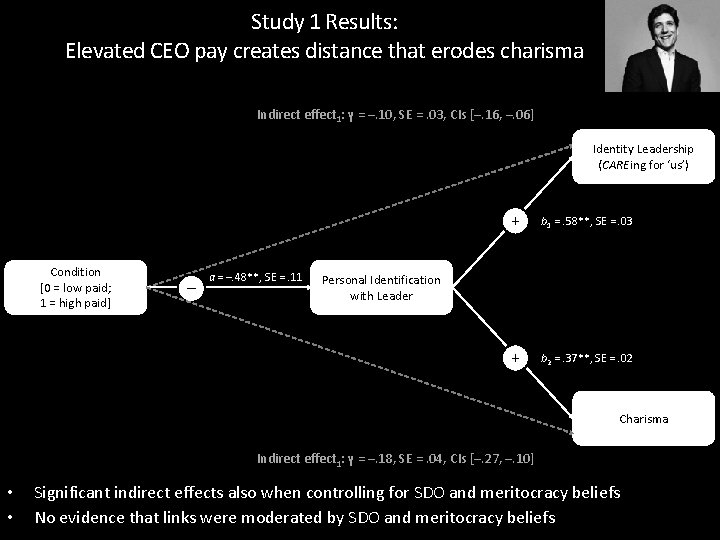

Study 1 Results: Elevated CEO pay creates distance that erodes charisma Indirect effect 1: γ = –. 10, SE =. 03, CIs [–. 16, –. 06] Identity Leadership (CAREing for ‘us’) Condition [0 = low paid; 1 = high paid] – a = –. 48**, SE =. 11 + b 1 =. 58**, SE =. 03 + b 2 =. 37**, SE =. 02 Personal Identification with Leader Charisma Indirect effect 1: γ = –. 18, SE =. 04, CIs [–. 27, –. 10] • • Significant indirect effects also when controlling for SDO and meritocracy beliefs No evidence that links were moderated by SDO and meritocracy beliefs

Study 1: Limitations Open Question • How does leader pay impact actual followers (i. e. , members of an organization / who work for the leader in question) • To what extent do results generalize to natural varying levels of CEO pay? Ø Field survey

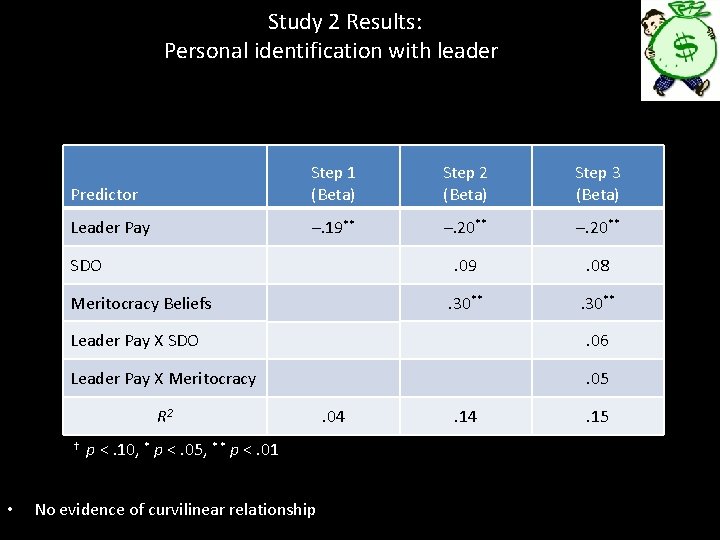

Study 2: Design Participants and Design • 444 US participants recruited via Prolific • Employees responded to the CEO (most senior leader /managing director) of their own organization • Participants responded to identical measures as in Study 1 Participants’ Leaders • Median estimated annual pay of US$200, 000 [Inter-quartile Range: $100, 000 to $685, 000] • Leader pay: “[Leader] is high-paid relative to other CEOs”: M=2. 40, SD=1. 57 on 1 -7 scale • Average of 54 years [Inter-quartile Range: 48 to 75 years] • 20% were female (88 female; 358 male)

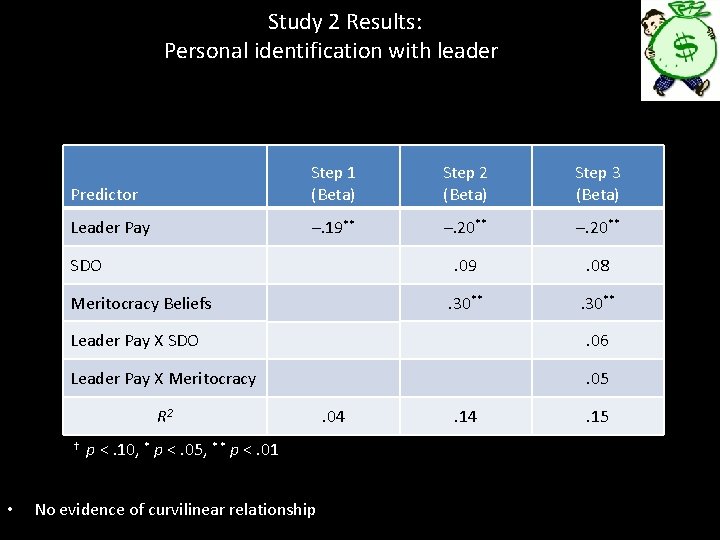

Study 2 Results: Personal identification with leader Predictor Step 1 (Beta) Step 2 (Beta) Step 3 (Beta) Leader Pay –. 19** –. 20** . 09 . 08 . 30** SDO Meritocracy Beliefs Leader Pay X SDO . 06 Leader Pay X Meritocracy . 05 R 2 ✝ • p <. 10, * p <. 05, * * p <. 01 No evidence of curvilinear relationship . 04 . 15

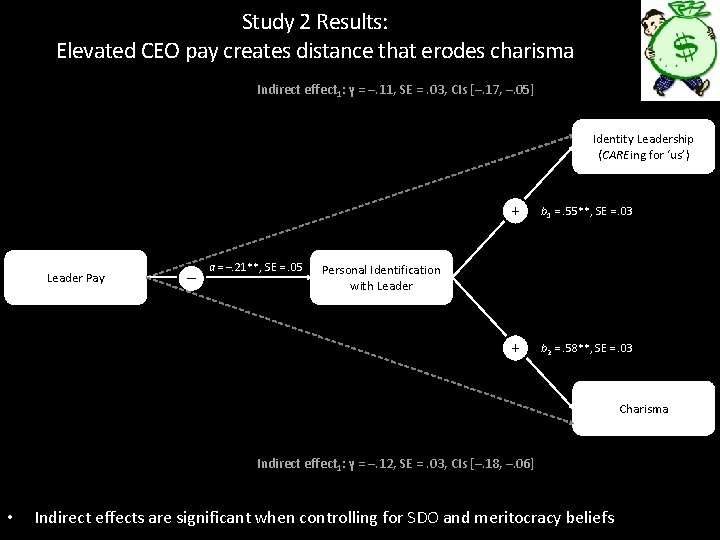

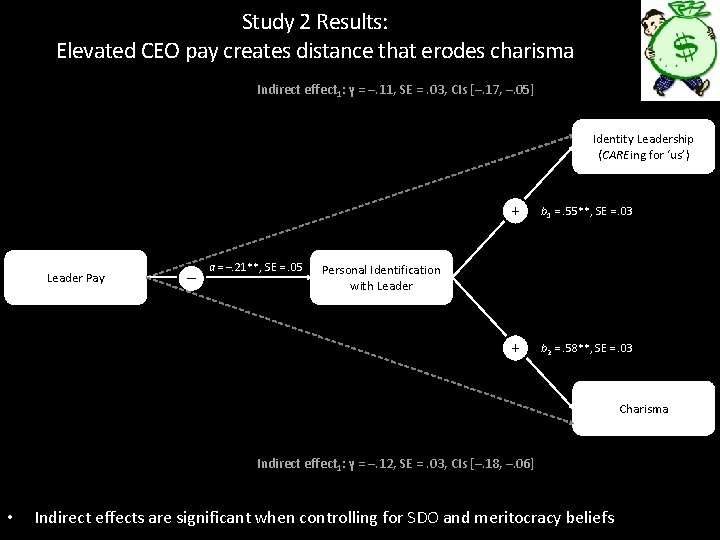

Study 2 Results: Elevated CEO pay creates distance that erodes charisma Indirect effect 1: γ = –. 11, SE =. 03, CIs [–. 17, –. 05] Identity Leadership (CAREing for ‘us’) Leader Pay – a = –. 21**, SE =. 05 + b 1 =. 55**, SE =. 03 + b 2 =. 58**, SE =. 03 Personal Identification with Leader Charisma Indirect effect 1: γ = –. 12, SE =. 03, CIs [–. 18, –. 06] • Indirect effects are significant when controlling for SDO and meritocracy beliefs

Identity economics meets identity leadership: Implications and conclusion • • • Significant externalities of prevailing ‘pay-for performance’ ideas in CEO pay • Little evidence that high incentives increase follower motivation to emulate leaders • On the contrary, elevated CEO pay diminishes followers’ sense of connection to that leader (and their sense that they are good leaders for ‘us’ and charismatic) • But to manage consequences, organizations restrict access to information about pay Increases in CEO pay are consistent with the abandonment of an ‘identity’ model in favor of one where the CEO has primary role of an agent for shareholders • Yet this approach reduces workers’ bond with their leaders which is likely to have significant consequences for the long-term viability of organizations Ironically, while elevated pay is typically justified by a desire to reward and inspire good leadership, it appears that it in fact achieves the very opposite.

Let’s open the discussion: Any questions, thoughts, or comments?

Exploring the world of business and economics

Exploring the world of business and economics Maastricht university economics and business economics

Maastricht university economics and business economics Elements of mathematical economics

Elements of mathematical economics Adaptive leadership theory

Adaptive leadership theory Situational leadership vs adaptive leadership

Situational leadership vs adaptive leadership Transactional leadership vs transformational leadership

Transactional leadership vs transformational leadership Congress

Congress What role do automobiles play in the great gatsby

What role do automobiles play in the great gatsby Science meets nature

Science meets nature Approaches meets masters

Approaches meets masters A generally restful like the horizon

A generally restful like the horizon Newton meets buzz and woody worksheet answers

Newton meets buzz and woody worksheet answers How do huck and jim dress on the raft

How do huck and jim dress on the raft Narrow band where the ocean meets land

Narrow band where the ocean meets land Academia meets industry

Academia meets industry Where today meets tomorrow

Where today meets tomorrow Piaget meets santa

Piaget meets santa Belle corinne meets the knight

Belle corinne meets the knight Macbeth meets the witches

Macbeth meets the witches Dan muse

Dan muse