Greece Hellenistic Period What is the Hellenistic Excerpts

- Slides: 19

Greece: Hellenistic Period

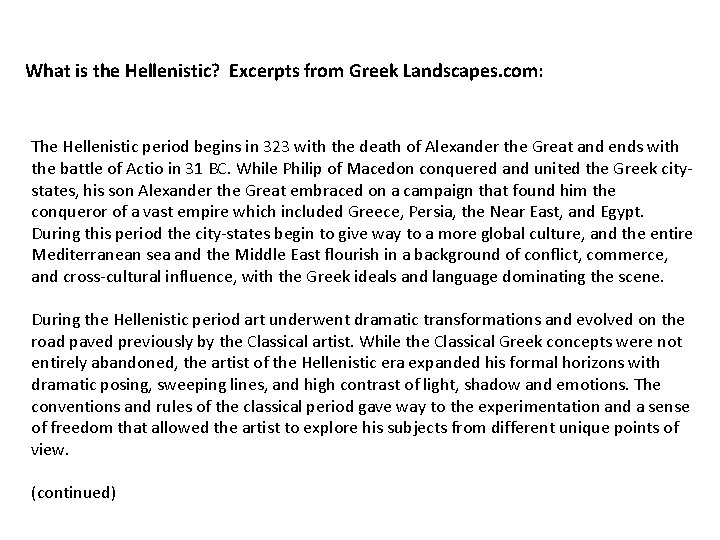

What is the Hellenistic? Excerpts from Greek Landscapes. com: The Hellenistic period begins in 323 with the death of Alexander the Great and ends with the battle of Actio in 31 BC. While Philip of Macedon conquered and united the Greek citystates, his son Alexander the Great embraced on a campaign that found him the conqueror of a vast empire which included Greece, Persia, the Near East, and Egypt. During this period the city-states begin to give way to a more global culture, and the entire Mediterranean sea and the Middle East flourish in a background of conflict, commerce, and cross-cultural influence, with the Greek ideals and language dominating the scene. During the Hellenistic period art underwent dramatic transformations and evolved on the road paved previously by the Classical artist. While the Classical Greek concepts were not entirely abandoned, the artist of the Hellenistic era expanded his formal horizons with dramatic posing, sweeping lines, and high contrast of light, shadow and emotions. The conventions and rules of the classical period gave way to the experimentation and a sense of freedom that allowed the artist to explore his subjects from different unique points of view. (continued)

During this period, the Idealism of classical art gave way to a higher degree of Naturalism which comes as a logical conclusion to the efforts of the great fourth century sculptors (Praxitelis, Skopas, and Lysipos) who worked towards a more realistic way of expressing the human figure. The subtle implications of greatness and humility of the high Classical era (see the Charioteer of Delphi) are replaced with bold expressions of energy and power. While the interest in deities and heroic themes was still of importance, the emphasis of Hellenistic art shifted from religious and naturalistic themes towards more dramatic human expression, psychological and spiritual preoccupation, and theatrical settings. The sculpture of this period abandons the self-containment of the earlier styles and appears to embrace its physical surroundings with dramatic groupings and creative landscaping of its context. The Nike of Samothrace for instance was posed at a sanctuary built high at the edge of a cliff with a reflective water pool and rocks as part of the landscape. Often the Hellenistic sculptor is not satisfied to only depict his subjects in true outward appearance, but he further strives to express their inner world, by the depiction of physical characteristics and postures that betray inner feelings, thoughts, and attitudes. In portraiture, the imperfections of the subject are often included in an effort to instill individual personality into the statues, or sometimes as a means of betraying the subject's qualities and attitudes. Eroticism gained popularity during this period and statues of Aphrodite, Eros, Satyrs, Dionysus, Pan, and even hermaphrodites are depicted in a multitude of configurations and styles. Statues of female nudes became popular in Hellenistic art and statues of Venus in various poses and attitudes adorn the halls of many museums around the world.

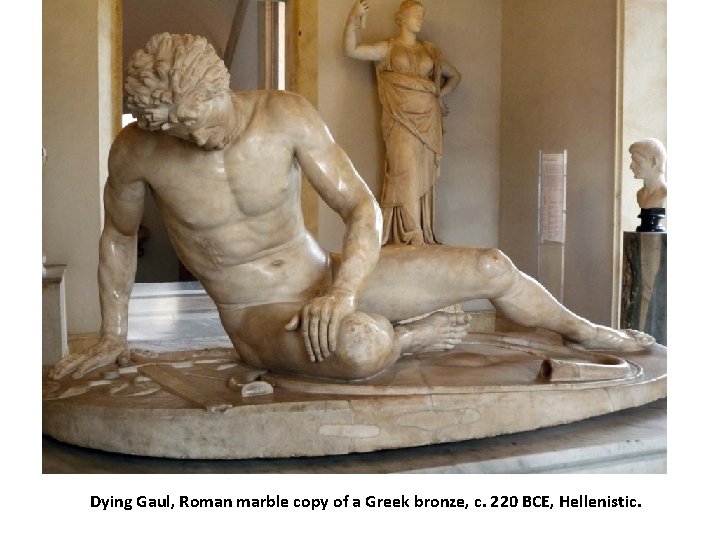

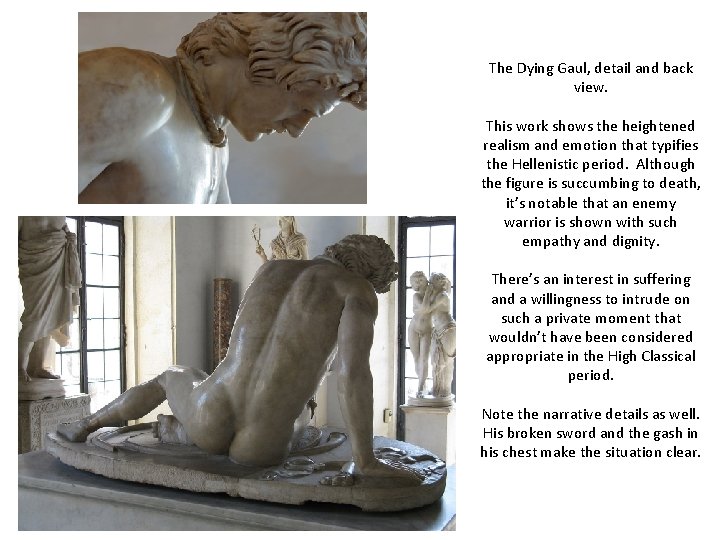

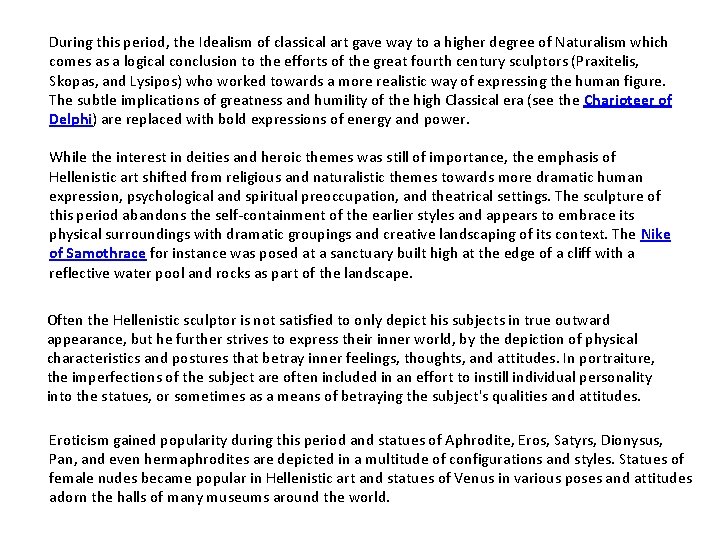

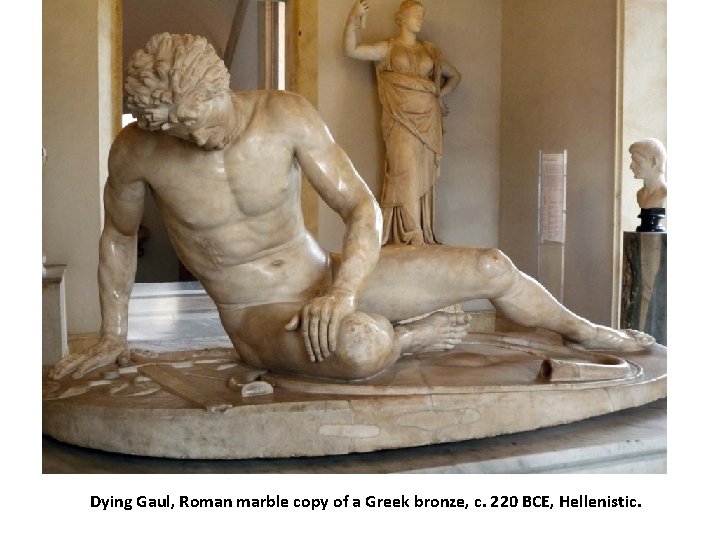

Dying Gaul, Roman marble copy of a Greek bronze, c. 220 BCE, Hellenistic.

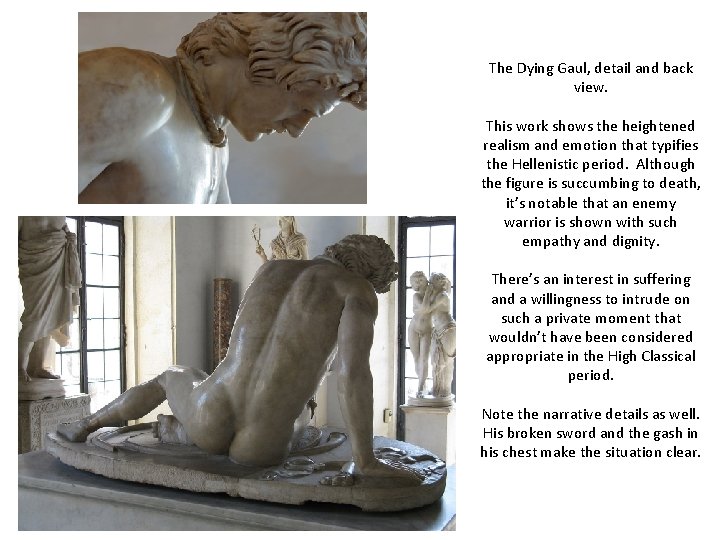

The Dying Gaul, detail and back view. This work shows the heightened realism and emotion that typifies the Hellenistic period. Although the figure is succumbing to death, it’s notable that an enemy warrior is shown with such empathy and dignity. There’s an interest in suffering and a willingness to intrude on such a private moment that wouldn’t have been considered appropriate in the High Classical period. Note the narrative details as well. His broken sword and the gash in his chest make the situation clear.

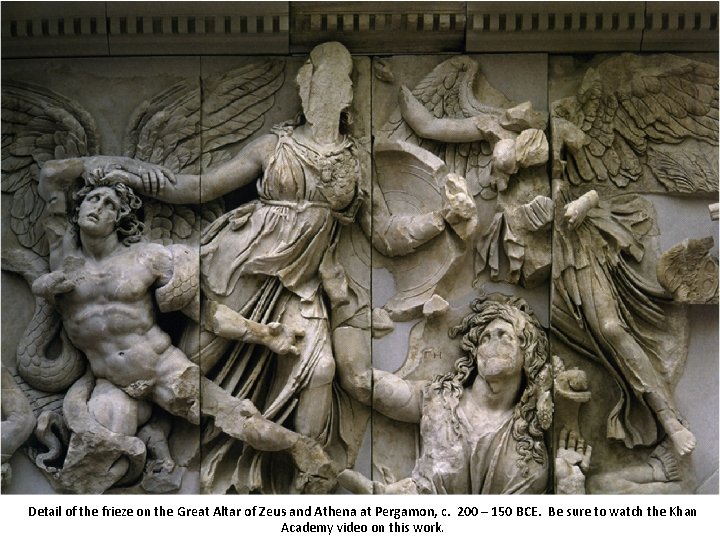

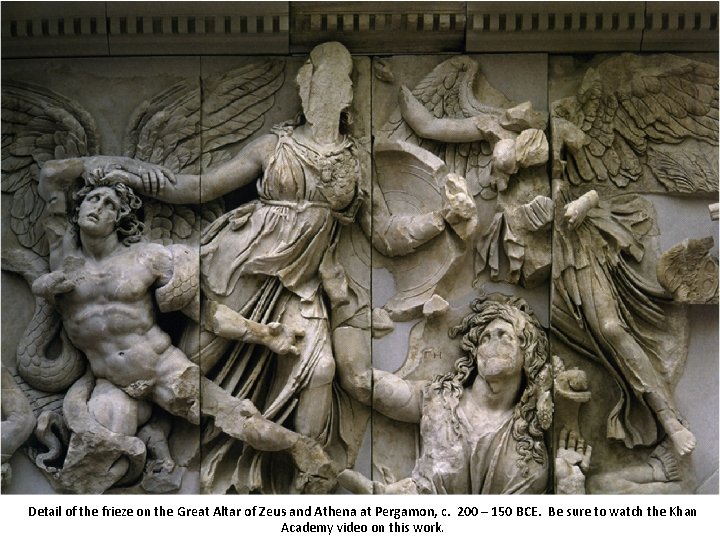

Detail of the frieze on the Great Altar of Zeus and Athena at Pergamon, c. 200 – 150 BCE. Be sure to watch the Khan Academy video on this work.

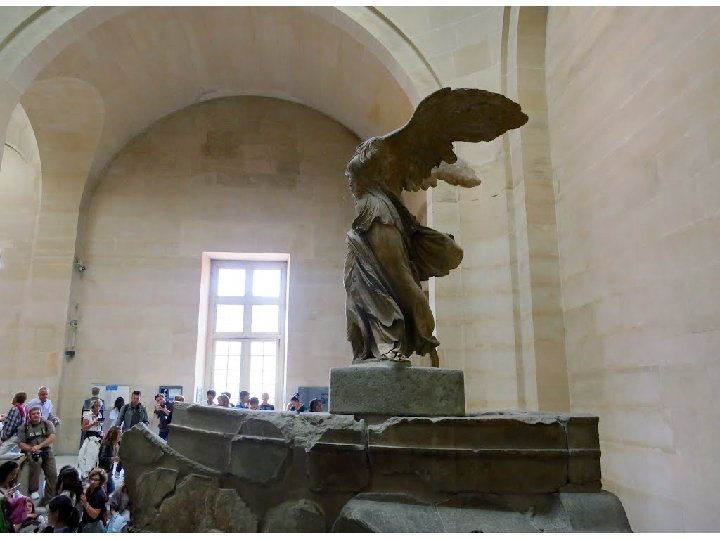

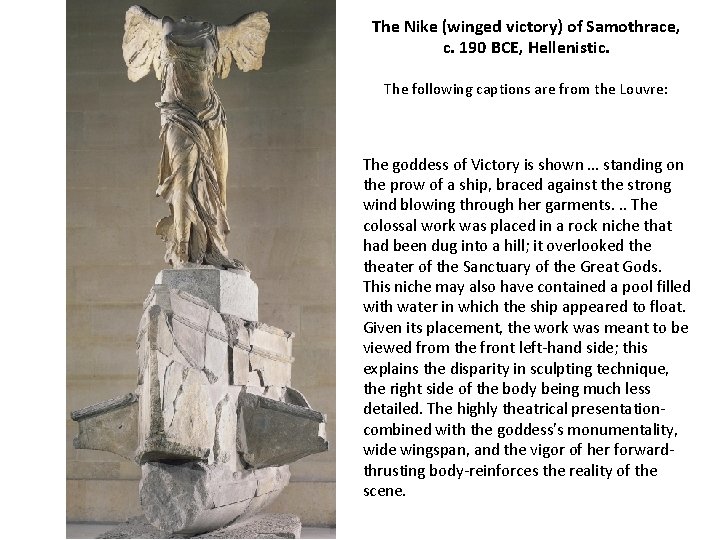

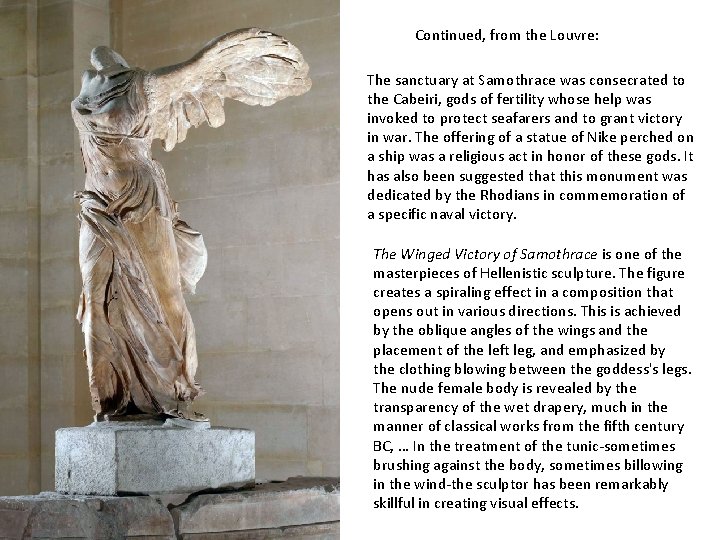

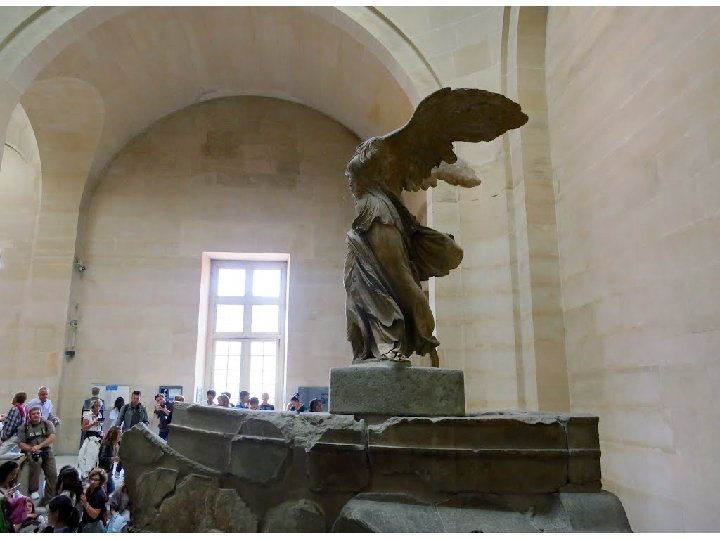

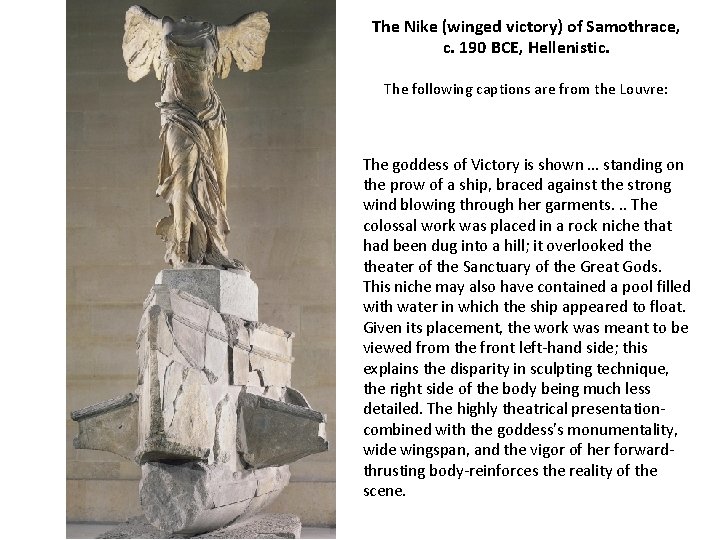

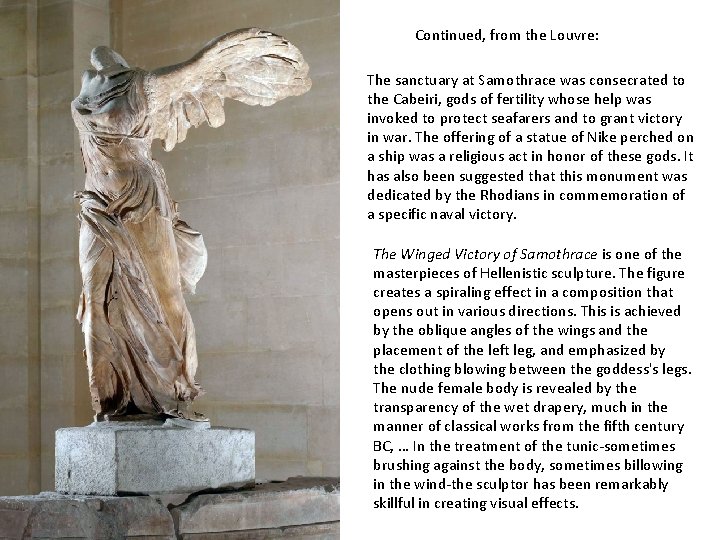

The Nike (winged victory) of Samothrace, c. 190 BCE, Hellenistic. The following captions are from the Louvre: The goddess of Victory is shown … standing on the prow of a ship, braced against the strong wind blowing through her garments. . . The colossal work was placed in a rock niche that had been dug into a hill; it overlooked theater of the Sanctuary of the Great Gods. This niche may also have contained a pool filled with water in which the ship appeared to float. Given its placement, the work was meant to be viewed from the front left-hand side; this explains the disparity in sculpting technique, the right side of the body being much less detailed. The highly theatrical presentationcombined with the goddess's monumentality, wide wingspan, and the vigor of her forwardthrusting body-reinforces the reality of the scene.

Continued, from the Louvre: The sanctuary at Samothrace was consecrated to the Cabeiri, gods of fertility whose help was invoked to protect seafarers and to grant victory in war. The offering of a statue of Nike perched on a ship was a religious act in honor of these gods. It has also been suggested that this monument was dedicated by the Rhodians in commemoration of a specific naval victory. The Winged Victory of Samothrace is one of the masterpieces of Hellenistic sculpture. The figure creates a spiraling effect in a composition that opens out in various directions. This is achieved by the oblique angles of the wings and the placement of the left leg, and emphasized by the clothing blowing between the goddess's legs. The nude female body is revealed by the transparency of the wet drapery, much in the manner of classical works from the fifth century BC, … In the treatment of the tunic-sometimes brushing against the body, sometimes billowing in the wind-the sculptor has been remarkably skillful in creating visual effects.

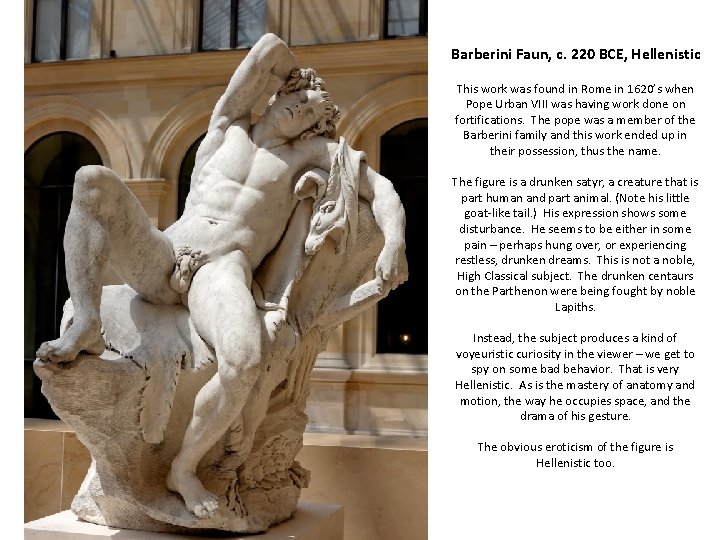

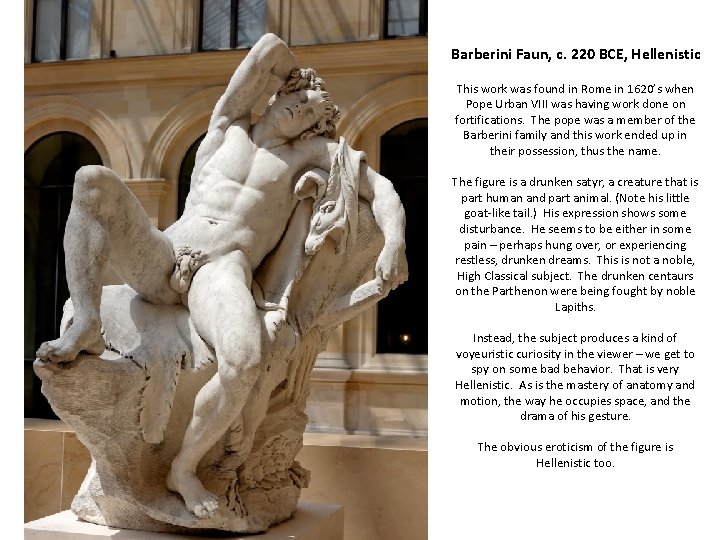

Barberini Faun, c. 220 BCE, Hellenistic This work was found in Rome in 1620’s when Pope Urban VIII was having work done on fortifications. The pope was a member of the Barberini family and this work ended up in their possession, thus the name. The figure is a drunken satyr, a creature that is part human and part animal. (Note his little goat-like tail. ) His expression shows some disturbance. He seems to be either in some pain – perhaps hung over, or experiencing restless, drunken dreams. This is not a noble, High Classical subject. The drunken centaurs on the Parthenon were being fought by noble Lapiths. Instead, the subject produces a kind of voyeuristic curiosity in the viewer – we get to spy on some bad behavior. That is very Hellenistic. As is the mastery of anatomy and motion, the way he occupies space, and the drama of his gesture. The obvious eroticism of the figure is Hellenistic too.

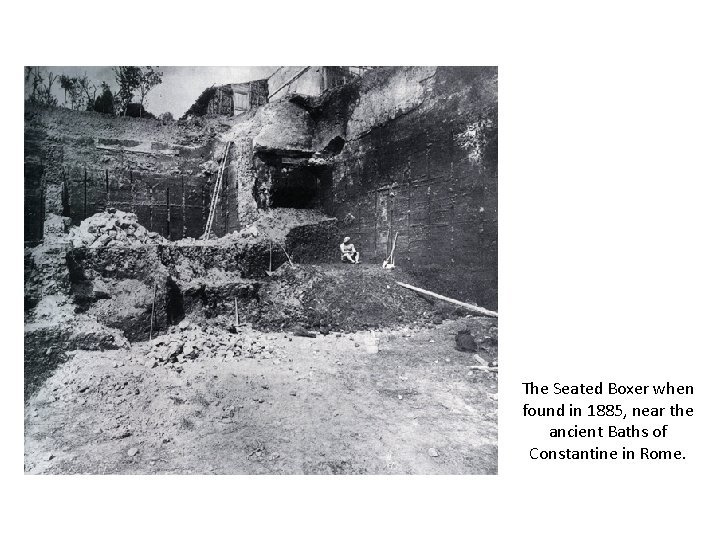

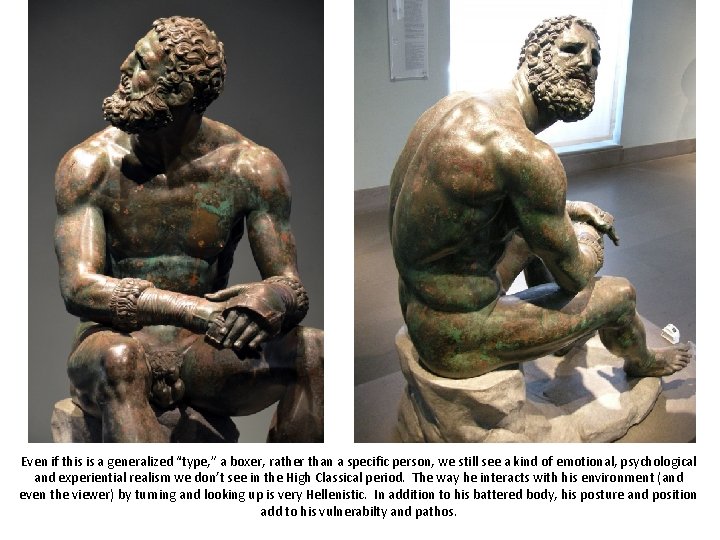

The Seated Boxer when found in 1885, near the ancient Baths of Constantine in Rome.

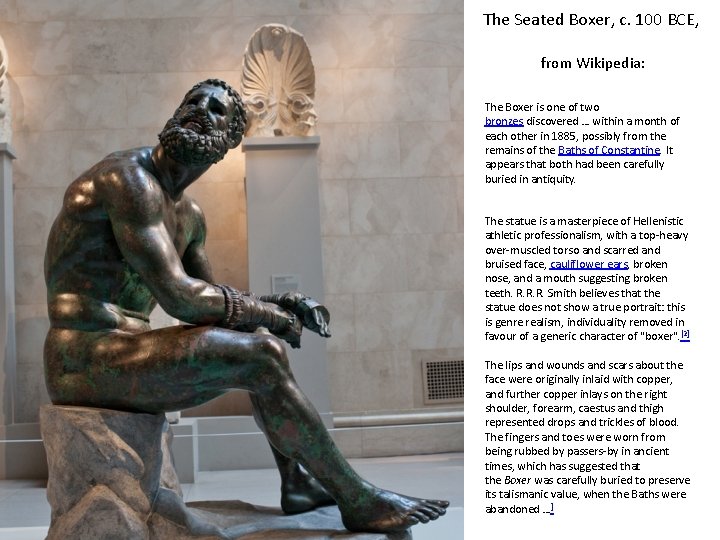

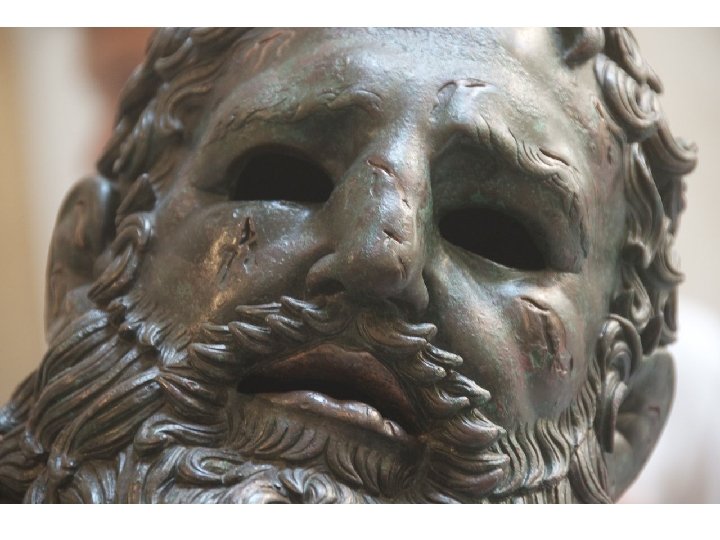

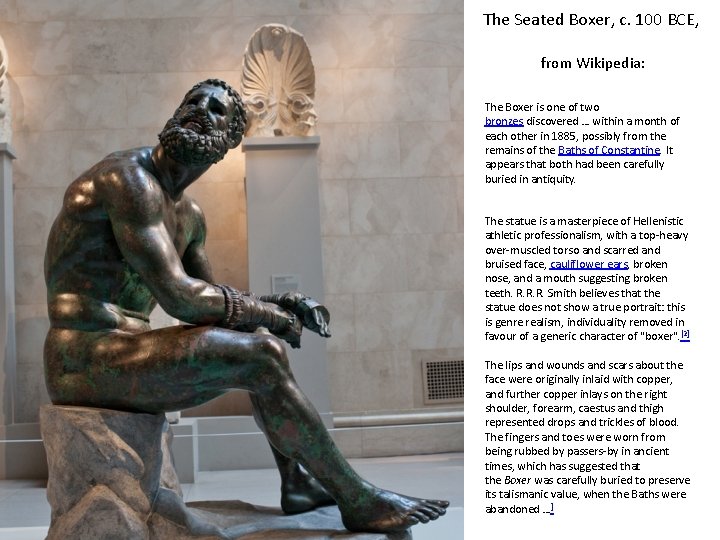

The Seated Boxer, c. 100 BCE, from Wikipedia: The Boxer is one of two bronzes discovered … within a month of each other in 1885, possibly from the remains of the Baths of Constantine. It appears that both had been carefully buried in antiquity. The statue is a masterpiece of Hellenistic athletic professionalism, with a top-heavy over-muscled torso and scarred and bruised face, cauliflower ears, broken nose, and a mouth suggesting broken teeth. R. R. R. Smith believes that the statue does not show a true portrait: this is genre realism, individuality removed in favour of a generic character of "boxer". [2] The lips and wounds and scars about the face were originally inlaid with copper, and further copper inlays on the right shoulder, forearm, caestus and thigh represented drops and trickles of blood. The fingers and toes were worn from being rubbed by passers-by in ancient times, which has suggested that the Boxer was carefully buried to preserve its talismanic value, when the Baths were abandoned …]

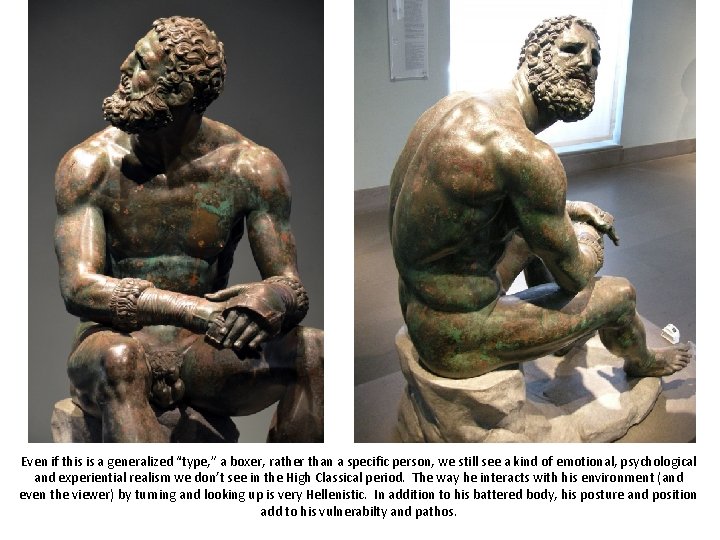

Even if this is a generalized “type, ” a boxer, rather than a specific person, we still see a kind of emotional, psychological and experiential realism we don’t see in the High Classical period. The way he interacts with his environment (and even the viewer) by turning and looking up is very Hellenistic. In addition to his battered body, his posture and position add to his vulnerabilty and pathos.

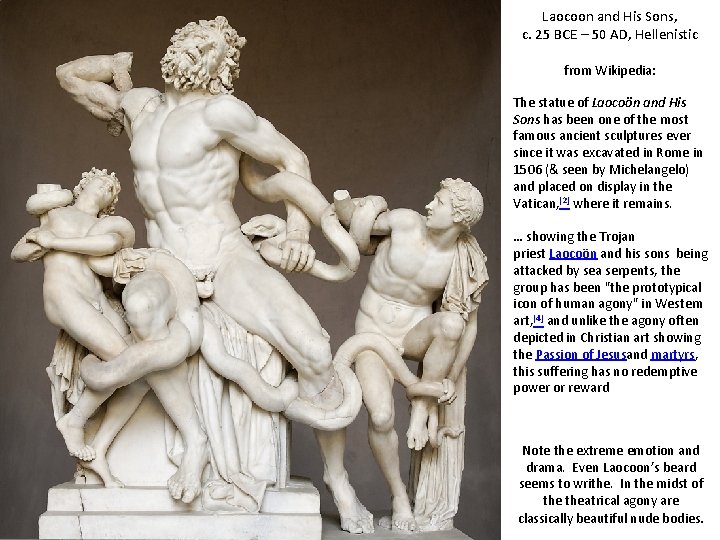

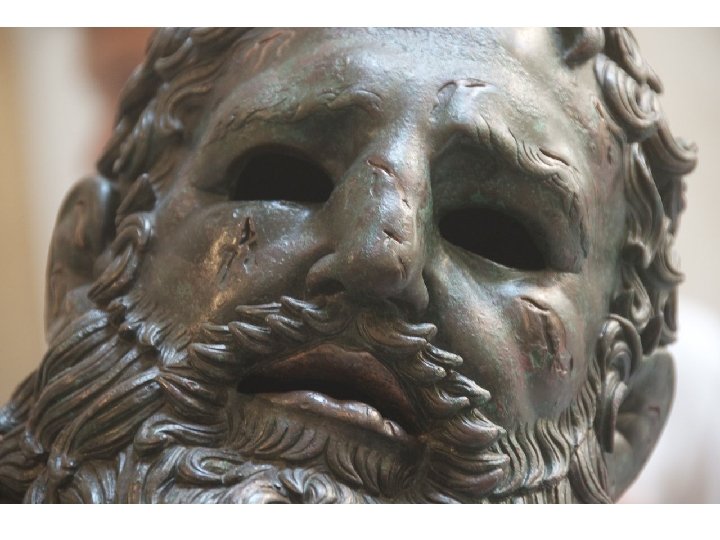

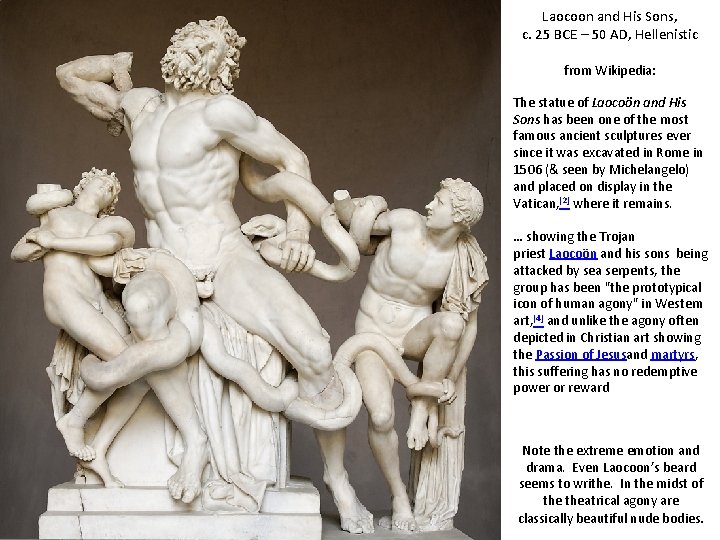

Laocoon and His Sons, c. 25 BCE – 50 AD, Hellenistic from Wikipedia: The statue of Laocoön and His Sons has been one of the most famous ancient sculptures ever since it was excavated in Rome in 1506 (& seen by Michelangelo) and placed on display in the Vatican, [2] where it remains. … showing the Trojan priest Laocoön and his sons being attacked by sea serpents, the group has been "the prototypical icon of human agony" in Western art, [4] and unlike the agony often depicted in Christian art showing the Passion of Jesusand martyrs, this suffering has no redemptive power or reward Note the extreme emotion and drama. Even Laocoon’s beard seems to writhe. In the midst of theatrical agony are classically beautiful nude bodies.