Grant Writing Session Part 1 A Primer on

- Slides: 20

Grant Writing Session Part 1: A Primer on Scientific Grant Writing Led by Dominik Biezonski, Ph. D

Dominik Biezonski, Ph. D Senior Scientific Grant Writer New York Genome Center, NYC

Part 1 Agenda 1 Overview of Grant Opportunities for Graduate Students/Post-Docs 2 Basics of Grant Structure Based on Principles of the Scientific Method 3 Tips for Effective Grant Writing (General and Science-Specific) 4 Grant Writing as a Career 5 Example SA Page

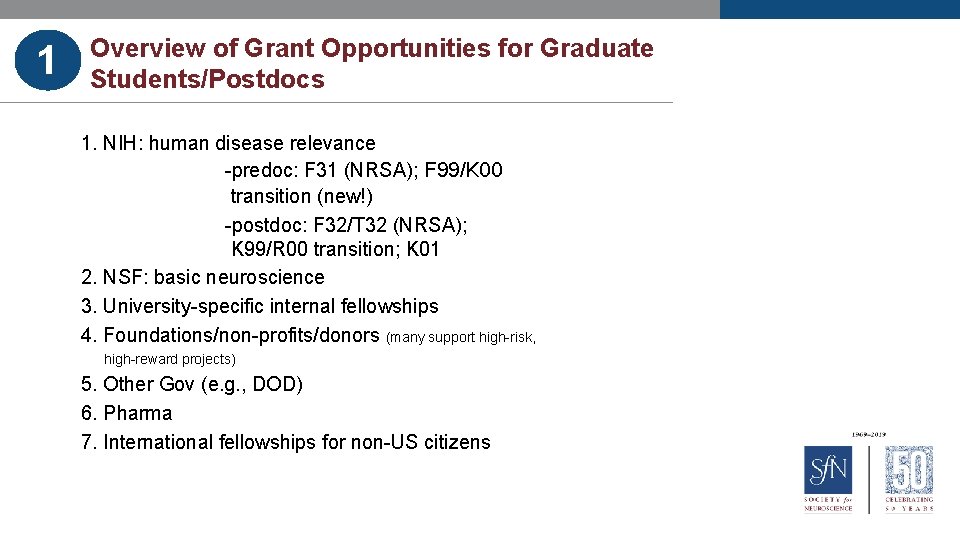

1 Overview of Grant Opportunities for Graduate Students/Postdocs 1. NIH: human disease relevance -predoc: F 31 (NRSA); F 99/K 00 transition (new!) -postdoc: F 32/T 32 (NRSA); K 99/R 00 transition; K 01 2. NSF: basic neuroscience 3. University-specific internal fellowships 4. Foundations/non-profits/donors (many support high-risk, high-reward projects) 5. Other Gov (e. g. , DOD) 6. Pharma 7. International fellowships for non-US citizens

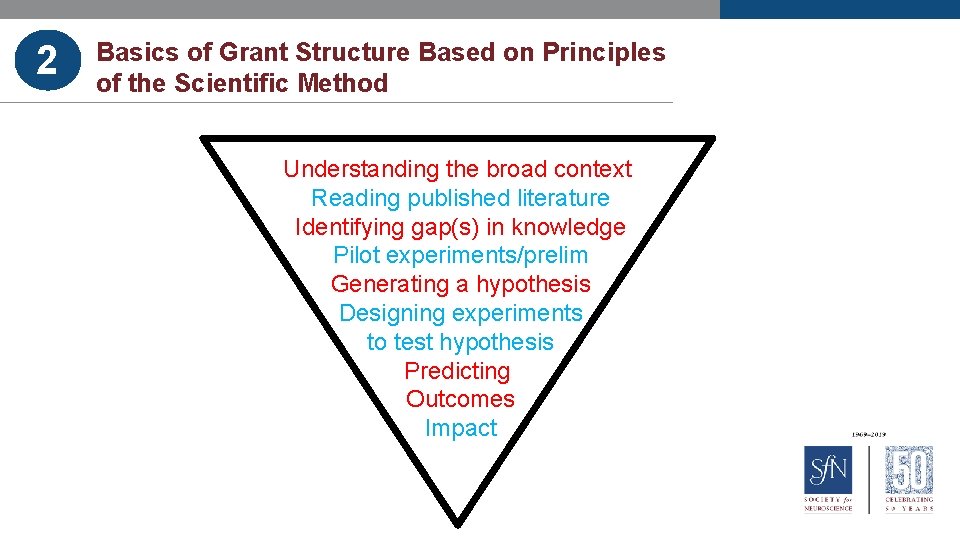

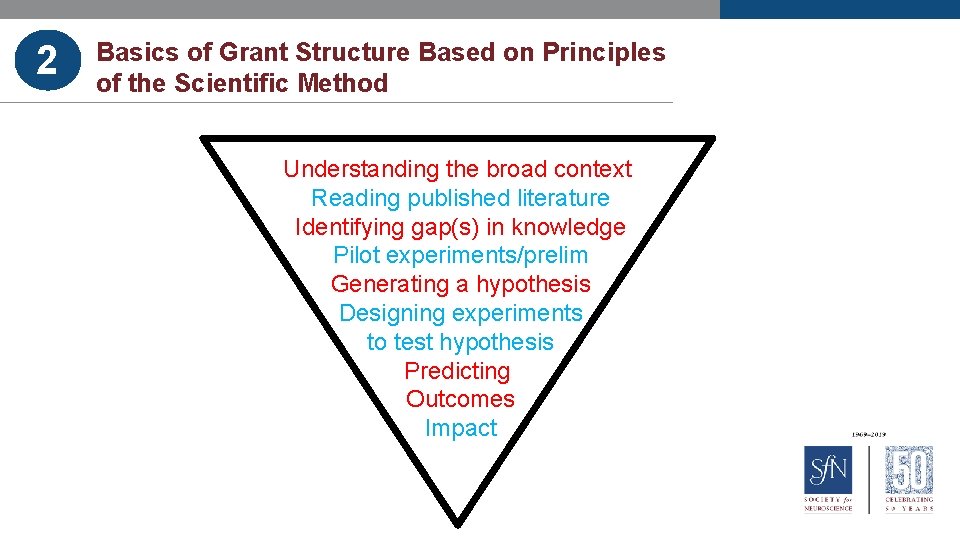

2 Basics of Grant Structure Based on Principles of the Scientific Method Understanding the broad context Reading published literature Identifying gap(s) in knowledge Pilot experiments/prelim Generating a hypothesis Designing experiments to test hypothesis Predicting Outcomes Impact

Basics of Grant Structure Based on Principles of the Scientific Method 2 Hypothesis vs. Prediction • A hypothesis is a statement of a general phenomenon in question, without bias or directionality • A prediction is an explicit statement of what you would expect to find if the hypothesis was true. • E. g. : “We hypothesize that vocal-learning brain circuits emerge from the specialized expression of a core genetic module conserved across vocal-learning species. We predict that constituting components of this genetic module in mice will enhance the mouse vocal system at the neural and behavioral level. ”

Tips for Effective Grant Writing (General 1) 3 • Know your audience (a. k. a. reviewers) and fundingsource specific writing style (e. g. , NIH vs. HHMI). Look at funded abstracts and examples. Ask for full grants from awardees to serve as templates. Carefully read all application instructions and adhere to proper formatting. • Craft a title and keep it in the upper header – this will help keep you focused as you’re writing • Keep paragraphs limited to one specific topic; start each paragraph with a sentence that introduces the crux of what you will be discussing • Use ACTIVE voice (vs. passive) when possible. Why? More concise, clear, and easy to logically follow. The less you cognitively tax your audience, the better (see: https: //webapps. towson. edu/ows/activepass. htm)

Tips for Effective Grant Writing (General 2) 3 • Limit jargon and abbreviations • The best writing is clear and concise; eliminate any redundancy/verbosity/extraneous phrasing/fluff/colloquialisms/informal language. Keep it simple and scientifically rigorous. • Simple schematics/diagrams/charts/tables can tell a thousand words. • OK to emphasize critical parts of your narrative with bolding/underlining/italicizing; use sparingly.

Tips for Effective Grant Writing (General 3) 3 • Sections, paragraphs, and ultimately sentences need to be logically linked with smooth transitions that leave no logical gaps. The most effective form of writing is one where the reader can logically follow your narrative to the point where they can predict what you’ll say next; when you then follow with a statement that matches their prediction, this maximizes ease of understanding and appreciation of your argument. • Overall, organization and clarity is central to effective science and scientific writing. Reviewers need to EASILY GRASP the information the first read-through. • Send sections to as many (different) people as you can to get feedback.

3 Tips for Effective Grant Writing (Science: Specific Aims Page, 1) • Extremely important part of a grant. Needs to be near-flawless by submission. Reviewers will come back to this for reference time and again. • Use reductionist approach (general -> specific): Intro and importance; gap(s) in the field/weaknesses in extant literature; your prelim data and innovative approaches that address said gap(s); specific hypothesis; Aims or Objectives that will test your hypothesis; predictions; and impact. Your rationale for your research should be strong and compelling. You need to instill excitement in your reviewers. • Need a clear, explicit hypothesis. Your hypothesis serves to anchor your Aims to a common theme • 1 -3 Aims or Objectives is typical, 4 is a stretch. Don’t be overly ambitious. Less is more. • Once completed, send to the program officer (PO) listed on the RFA. Ask for their thoughts regarding fit and scientific promise. This is critical and something that should always be done in advance of submission.

3 Tips for Effective Grant Writing (Science: Specific Aims Page, 2) • Aims should cover independent experiments aimed at testing various facets of your hypothesis. Aims should therefore be independent of each other; interdependence spells death for a grant as null findings in a preceding Aim will necessarily obviate the following Aim. • It’s good practice to briefly spell out your experimental approach in each Aim, and what you predict you will find. Include in each Aim with how your findings will update the gap in the field (recommended by NIH). Always circle back to how your research will fill the gap and inform the veracity of your hypothesis. • Finish with an “Impact” statement restating the problem, describing why your approach is important and novel, and how your results will move the field forward.

3 Tips for Effective Grant Writing (Science: Research Strategy, 1) • Research question must be significant and within the priorities of your funding source. • Research must be innovative, both in its approach and the findings it will generate. If research and/or approach are similar to what has been done in the lab or field, need strong rationale for what makes your project distinct and worth funding. • Paradigm-shifting hypotheses must be strongly justified.

3 Tips for Effective Grant Writing (Science: Research Strategy, 2) • Strong preliminary data is typically crucial. There are exceptions to this e. g. , R 21 or explicitly exploratory grants, federal or private. • For NIH, avoid experiments that will yield descriptive findings (observing something in general) except where necessary (tracing studies, for e. g. ). Reviewers much prefer experiments where an independent variable is manipulated, and you have some predictions about how that impacts your dependent variable, as causal links can be made. NSF is presumably more forgiving with such observational approaches. • Experiments should be feasible and supported by either the lit or prelim data. If you can’t do the technique, add collaborators/consultants/co-PIs, etc. Everyday techniques can simply be cited.

3 Tips for Effective Grant Writing (Science: Research Strategy, 3) • Animal numbers should be stated and justified by power analyses (e. g. , G*Power) or existing lit. • Statistical approaches should be discussed and should be appropriate. • Pitfalls and alternative approaches should be discussed. • NIH only: new rigor and reproducibility requirements for R’s, maybe K’s. • Throughout, circle back to your hypothesis and how your experiments and predicted results will illuminate the phenomenon in question.

4 Grant Writing as a Career • It’s an emerging career, so jobs are few and far between. Search Glassdoor for opportunities in your area. • The earlier you start, the more qualified you’ll be come as this continues to grow, which it will given the financial logic of paying a grant writer to secure much more funds than their compensation. • • If writing for single PI, you essentially become their ghost writer, from coming up with original ideas/experiments to finding appropriate RFAs to writing and submitting the whole grant yourself. Some PIs may get more involved than others (the more involved, the better). You essentially have to ‘become’ the PI and try to write from their perspective, and with their level of expertise. • • Being at the forefront of experience will help you secure such jobs down the line, at higher pay and other benefits, especially as academic jobs are harder to obtain. This can be difficult if you’re new to the field, but rewarding if you get the PI funded as you’ve directly contributed to their success. May not pay very well for the level of qualification you need to perform this job sufficiently. Also, no room for growth. • Possibility to work remotely on occasion can be a nice plus, however.

4 Grant Writing as a Career • If writing for an institution, you help an array of investigators brainstorm ideas and put them to paper; find appropriate RFAs; construct the grant through back and forth revisions; help in the submission process. • This can also be challenging as you have to strongly familiarize yourself with each PIs research history and what they want to do next, which can be broad and requiring mastery within the span of a week or two. However, less is expected of you in terms of de novo primary writing; seen more as a collaborative process between you and each PI. • Typically, the PI will be responsible for their own submission so less pressure than writing for a single PI. • • It’s more interesting down the line as many more topics are covered. • Salary may be higher depending on institution (academic vs. non-profit vs. for profit). There may be room for growth as teams of grant writers can be hired to partner with subsets of PIs.

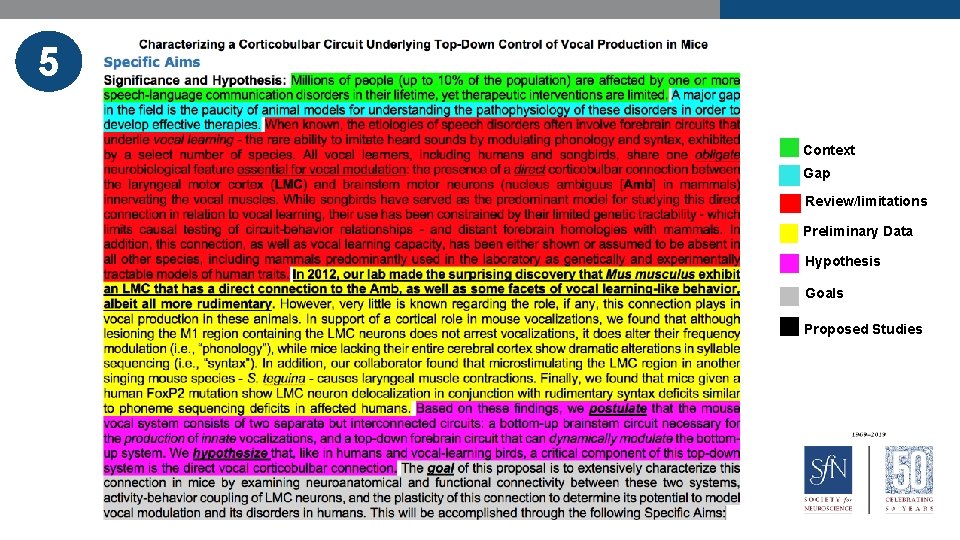

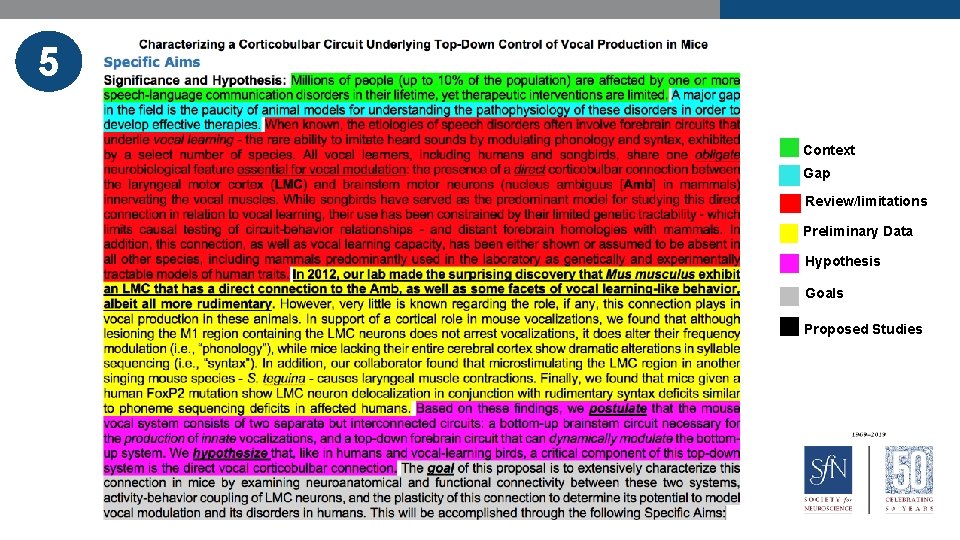

5 Specific Aims Color-Coded Example Context Gap Review/limitations Preliminary Data Hypothesis Goals Proposed Studies

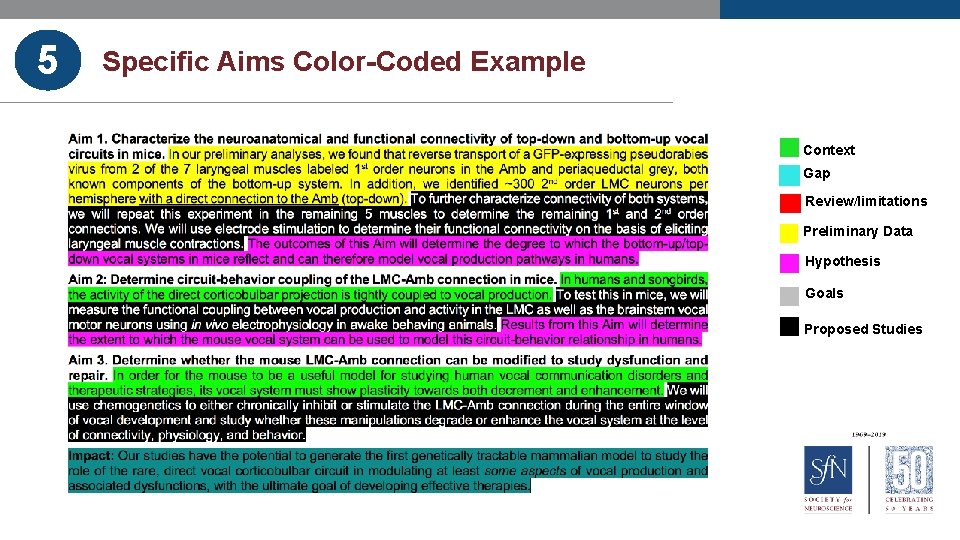

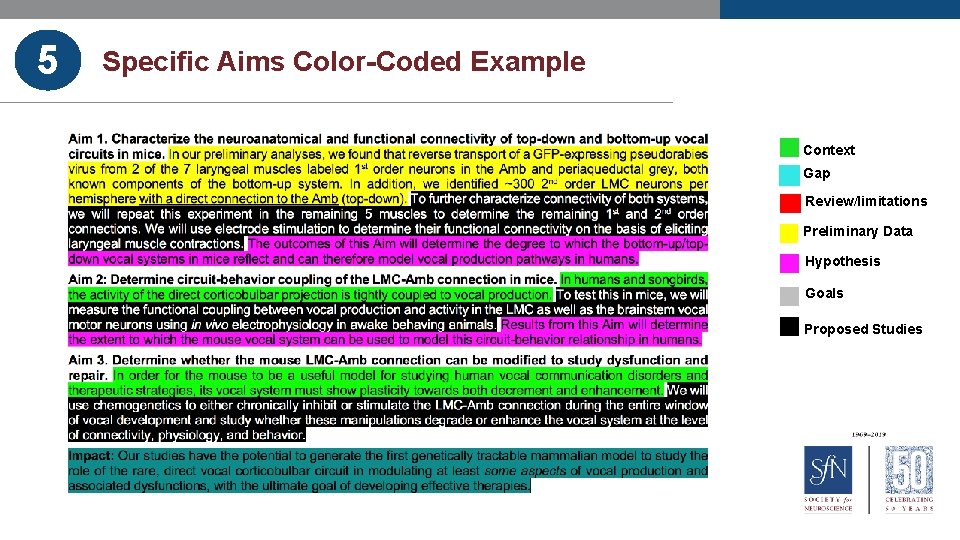

5 Specific Aims Color-Coded Example Context Gap Review/limitations Preliminary Data Hypothesis Goals Proposed Studies

Resources • • https: //www. braininitiative. nih. gov/funding/coming-xml. htm • • https: //public. csr. nih. gov/aboutcsr/News. And. Publications/Pages/Insiders. Guide. aspx http: //www 2. rockefeller. edu/sr-pd/index. php? page=tools • (includes boiler plates!) EXCELLENT: https: //www. niaid. nih. gov/grants-contracts/prepare-your-application Also really good: https: //grants. nih. gov/news/virtual-learning/podcasts. htm https: //www. niaid. nih. gov/grants-contracts/sample-applications https: //grants. nih. gov/grants/peer/reviewer_guidelines. htm https: //nsf. gov/pubs/policydocs/pappg 17_1/index. jsp For more coherent oral communication http: //www. northwestern. edu/climb/resources/oralcommunication-skills/index. html and for written communication. http: //www. northwestern. edu/climb/resources/writtencommunication/index. html.

Part 1 Q&A Dominik Biezonski, Ph. D Senior Scientific Grant Writer New York Genome Center, NYC