French New Wave The French New Wave or

- Slides: 11

French New Wave

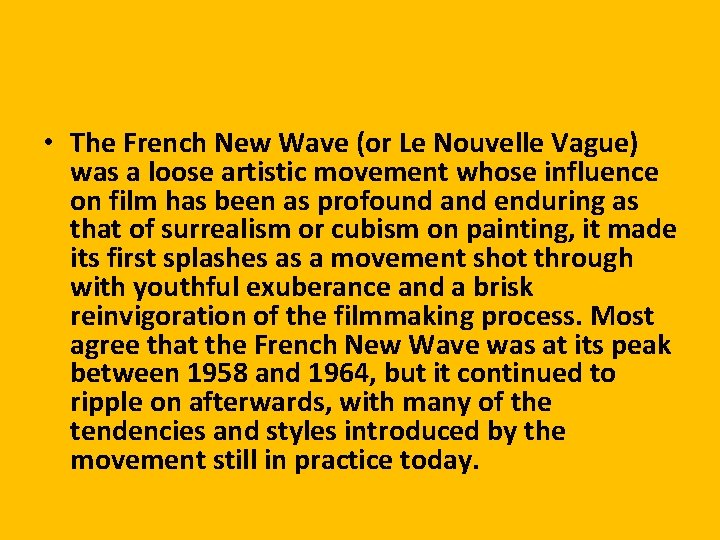

• The French New Wave (or Le Nouvelle Vague) was a loose artistic movement whose influence on film has been as profound and enduring as that of surrealism or cubism on painting, it made its first splashes as a movement shot through with youthful exuberance and a brisk reinvigoration of the filmmaking process. Most agree that the French New Wave was at its peak between 1958 and 1964, but it continued to ripple on afterwards, with many of the tendencies and styles introduced by the movement still in practice today.

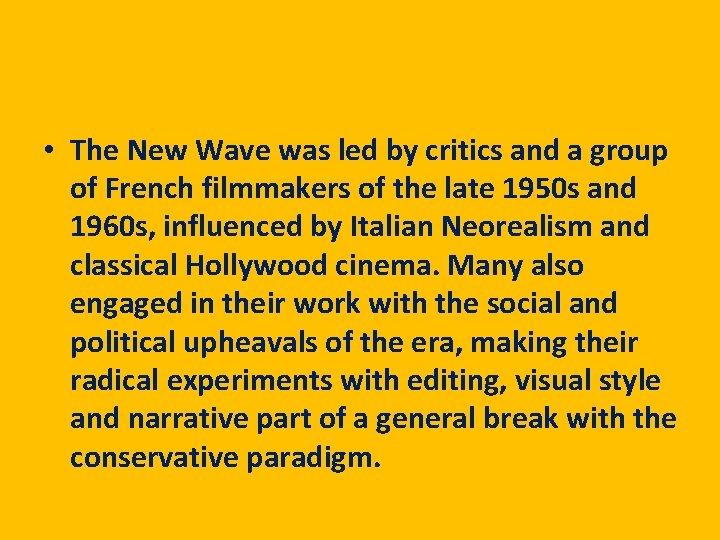

• The New Wave was led by critics and a group of French filmmakers of the late 1950 s and 1960 s, influenced by Italian Neorealism and classical Hollywood cinema. Many also engaged in their work with the social and political upheavals of the era, making their radical experiments with editing, visual style and narrative part of a general break with the conservative paradigm.

Le Background • Immediately after World War II, France, like most of the rest of Europe, was in a major state of flux and upheaval; in film, it was a period of great transition. During the German Occupation (1940 -45), many of France's greatest directors (René Clair, Jean Renoir, Jacques Feyder among them) had gone into exile. After the traumatic experience of war, a generation gap of sorts emerged between the more "old school" French classic filmmakers and a younger generation who set out to do things differently.

• In the 50 s, a collective of intellectual French film critics, led by André Bazin and Jacques Donial. Valcroze, formed the groundbreaking journal of film criticism Cahiers du Cinema. They, in turn, had been influenced by the writings of French film critic Alexandre Astruc, who had argued for breaking away from the "tyranny of narrative" in favor of a new form of film (and sound) language. The Cahiers critics gathered by Bazin and Doniol-Valcroze were all young cinephiles who had grown up in the post-war years watching mostly great American films that had not been available in France during the Occupation.

• Cahiers had two guiding principles: 1) A rejection of classical montage-style filmmaking (favored by studios up to that time) in favor of: miseen-scene, or, literally, "placing in the scene" (favoring the reality of what is filmed over manipulation via editing), the long take, and deep composition; and 2) A conviction that the best films are a personal artistic expression and should bear a stamp of personal authorship, much as great works of literature bear the stamp of the writer. This latter tenet would be dubbed by American film critic Andrew Sarris the "auteur (author) theory. "

• New Wave critics and directors studied the work of western classics and applied new avant garde stylistic direction. The low-budget approach helped filmmakers get at the essential art form and find what, to them, was a much more comfortable and honest form of production. Charlie Chaplin, Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles, Howard Hawks, John Ford, and many other forward-thinking film directors were held up in admiration while standard Hollywood films bound by traditional narrative flow were strongly criticized.

Cinema du Papa • Classic French cinema adhered to the principles of strong narrative, creating what Godard described as an oppressive and deterministic aesthetic of plot. In contrast, New Wave filmmakers made no attempts to suspend the viewer's disbelief; in fact, they took steps to constantly remind the viewer that a film is just a sequence of moving images, no matter how clever the use of light and shadow. The result is a set of oddly disjointed scenes without attempt at unity; or an actor whose character changes from one scene to the next; or sets in which onlookers accidentally make their way onto camera along with extras, who in fact were hired to do just the same.

• At the heart of New Wave technique is the issue of money and production value. In the context of social and economic troubles of a post-World War II France, filmmakers sought low-budget alternatives to the usual production methods. Half necessity and half vision, New Wave directors used all that they had available to channel their artistic visions directly to theatre.

• Many of the French New Wave's favorite conventions actually sprang not only from artistic tenets but from necessity and circumstance. These critics-turned-filmmakers knew a great deal about film history and theory but a lot less about film production. In addition, they were, especially at the start, working on low budgets. Thus, they often improvised with what schedules and materials they could afford. Out of all this came a group of conventions that were consistently used in the majority of French New Wave films, including:

• Jump cuts: a non-naturalistic edit, usually a section of a continuous shot that is removed unexpectedly, illogically • · Shooting on location • · Natural lighting • · Improvised dialogue and plotting • · Direct sound recording • · Long takes