Ethical Frameworks What are ethical frameworks Moral reasoning

- Slides: 23

Ethical Frameworks

What are ethical frameworks? • Moral reasoning requires a set of principles or values to structure our thinking. Ethical frameworks offer a way to “frame” our understanding. • What are ethical frameworks? A set of codes or values or a method of reasoning that helps us to distinguish right from wrong. • Ethical frameworks both intertwine with one another and sometimes compete.

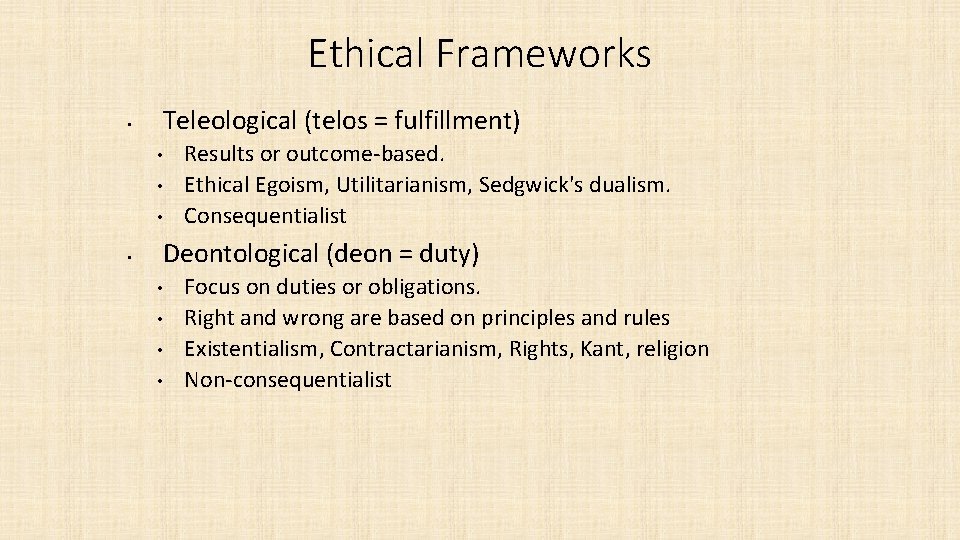

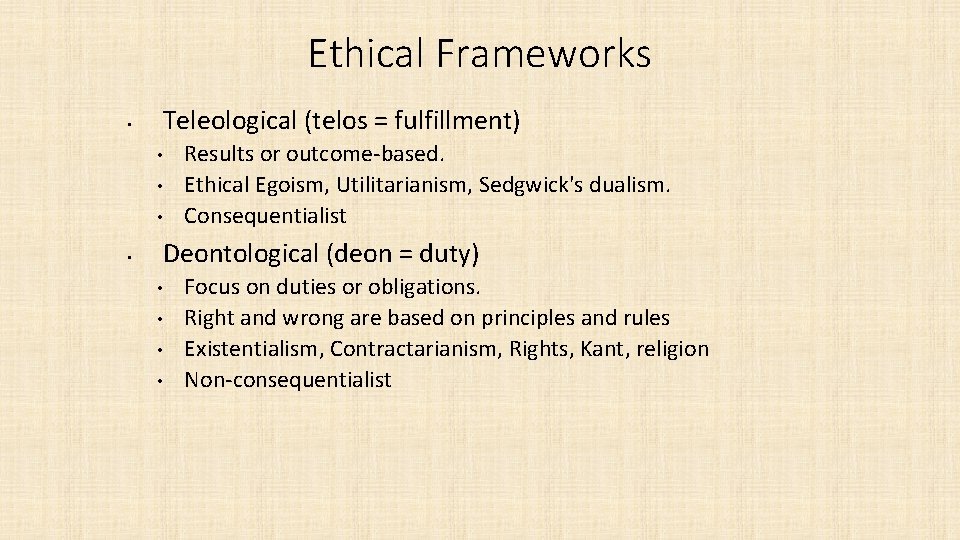

Ethical Frameworks • Teleological (telos = fulfillment) • • Results or outcome-based. Ethical Egoism, Utilitarianism, Sedgwick's dualism. Consequentialist Deontological (deon = duty) • • Focus on duties or obligations. Right and wrong are based on principles and rules Existentialism, Contractarianism, Rights, Kant, religion Non-consequentialist

Teleological Frameworks

Egoism Self-interest plays a major role in our motivations. We only really understand our own interests. Knowledge of the true needs of others is not possible. Ethical Egoism: Self-interest is ethical if it contains benefits to others. Rational self-interest: Surrendering short term interests for long-term interests. Allowing others to pursue their own interests is sometimes in our interests too.

Thomas Hobbes and the beggar: When seen giving money to a beggar and questioned about his motive, Hobbes said gave to alleviate his own suffering, since it caused him pain to see the beggar in such a condition. Modern advocates: Ayn Rand in Atlas Shrugged and The Fountainhead. Objectivism: A heroic philosophy. We can only excel in our lives through political and economic freedom. To excel is to pursue self excellence.

Criticisms • Self-interest does not always benefit others. • Examples: Vices as accusations: Selfish, self-centered, narcissistic. • Individuals interpret self-interest differently. • Differences in individual character formations. • Sometimes self-interest is not reflected in our behavior. • Acts of self-less heroism: Man in the Potomac

Utilitarianism Jeremy Bentham (1789) John Stuart Mill (1863). Utility: State of being useful, profitable or beneficial. “The creed which accepts as the foundation of morals, Utility, or the Greatest-Happiness Principle, holds that actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness, wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness. By happiness is intended pleasure, and the absence of pain; by unhappiness, pain, and the privation of pleasure. ” John Stuart Mill, Utilitarianism

Key Concept: Greatest good (happiness) for the greatest number. “Create all the happiness you are able to create; remove all the misery you are able to remove. Every day will allow you, --will invite you to add something to the pleasure of others, --or to diminish something of their pains. ” Jeremy Bentham Emphasis on rational choice. This may look like a cost-benefit analysis.

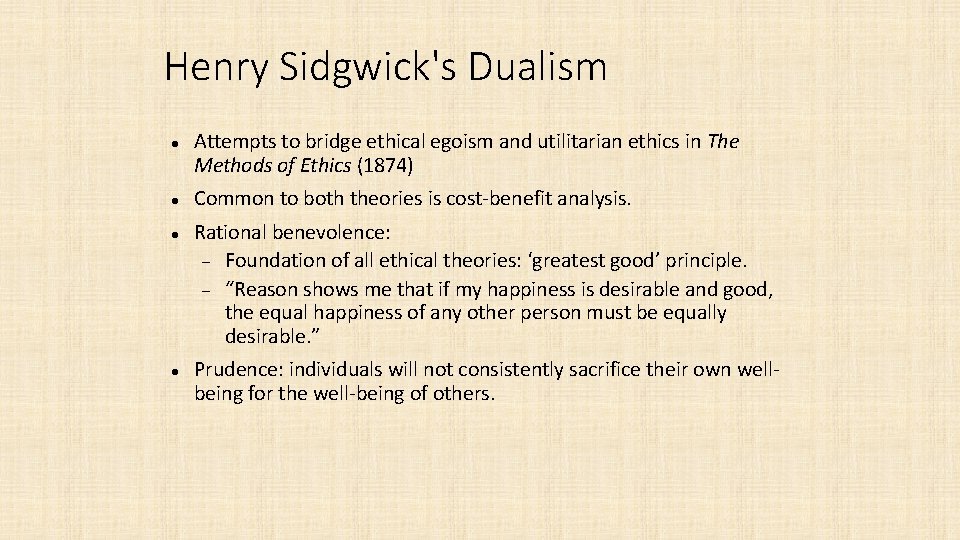

Henry Sidgwick's Dualism Attempts to bridge ethical egoism and utilitarian ethics in The Methods of Ethics (1874) Common to both theories is cost-benefit analysis. Rational benevolence: Foundation of all ethical theories: ‘greatest good’ principle. “Reason shows me that if my happiness is desirable and good, the equal happiness of any other person must be equally desirable. ” Prudence: individuals will not consistently sacrifice their own wellbeing for the well-being of others.

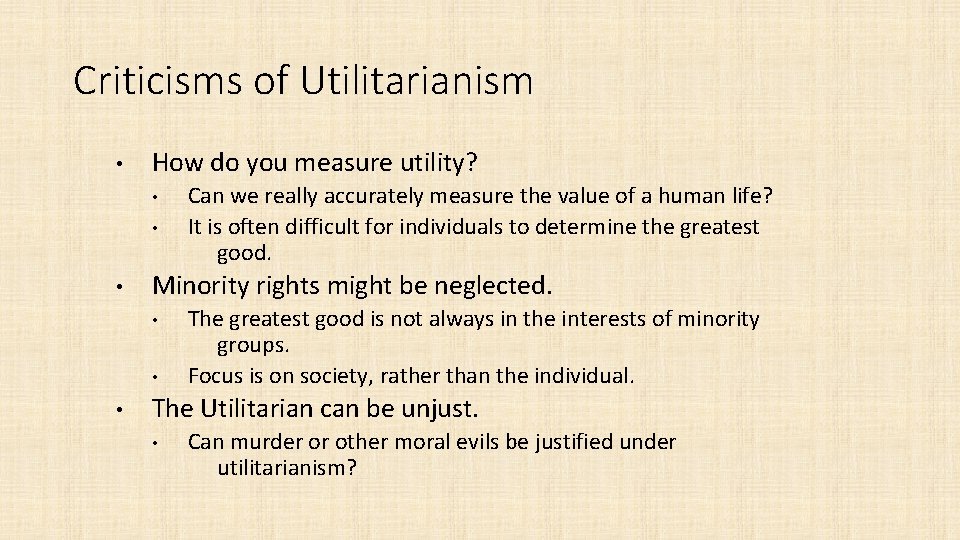

Criticisms of Utilitarianism • How do you measure utility? • • • Minority rights might be neglected. • • • Can we really accurately measure the value of a human life? It is often difficult for individuals to determine the greatest good. The greatest good is not always in the interests of minority groups. Focus is on society, rather than the individual. The Utilitarian can be unjust. • Can murder or other moral evils be justified under utilitarianism?

Deontological Frameworks

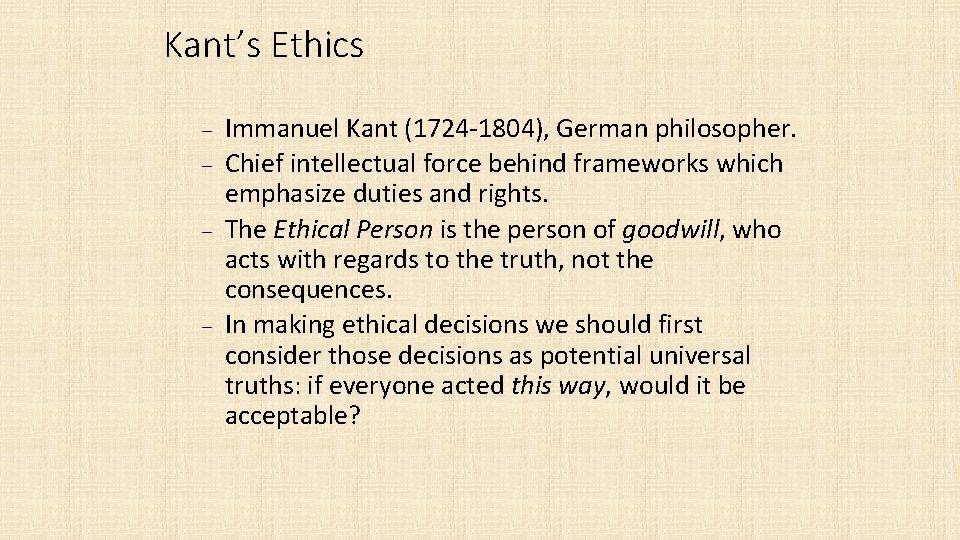

Kant’s Ethics Immanuel Kant (1724 -1804), German philosopher. Chief intellectual force behind frameworks which emphasize duties and rights. The Ethical Person is the person of goodwill, who acts with regards to the truth, not the consequences. In making ethical decisions we should first consider those decisions as potential universal truths: if everyone acted this way, would it be acceptable?

Categorical Imperative: “Act only on that maxim whereby thou can at the same time will that it should become universal law. ” Kant’s Four Examples: man contemplating suicide, borrowing money without intending to repay it, talented man trying to decide whether he should cultivate his talent or remain idle, prosperous man considering the misery of others.

Contractarianism John Locke (1690 s), Jean-Jacques Rousseau (The Social Contract, 1762). • • • To belong to a society, we agree to certain duties and responsibilities; IE, we agree to a “social contract. ” Society in turn agrees to honor my natural rights as an individual. Guiding principles • equality of treatment • equality of opportunity. John Rawls’ A Theory of Justice (1971). • Rawls’ Veil of Ignorance: • What would be the principles we would all agree to if we did not know how things are?

Rights and Justice • Rights are an entitlement. They emphasize the inherent dignity and worth of the individual. They are universal, regardless of laws to the contrary. • UN Declaration of Human Rights is an attempted codification of this concept. • Two Types of Rights: • Negative Rights • Rights cannot be taken away. • Emphasized in the 17 th/18 th century in our time by conservatives. • Examples: Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Conscience • Positive Rights • These rights must be provided by society for the individual. • Emphasized by 19 th and 20 th century liberals. • Example: Right to healthcare. Right to education.

Justice and Fairness • Justice and fairness is foundational to any society. • Law interprets rights and duties. The rights of individuals and society must be balanced. • Operates in terms of prohibitions and restrictions, both for society and the individual. • The rights of individuals should not always be subordinate to the rights of the society, but the rights of individuals are sometimes restricted in the interests of society.

• Libertarianism • Emphasis on the free will, or liberty, of the individual. • Society exists to protect citizens from force, fraud and theft. • Leading proponent, Robert Nozick • Social Justice Movement • Principle of economic and social equality • Inequalities can exist as long as the least advantaged is not worse off (the difference principle) • Inequalities can exist as long as everyone has access to the most privileged position

Existentialism Soren Kierkegaard, Frederic Nietzsche, Arthur Schopenhauer (19 th century); Jean Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, Martin Heidegger, Simone de Beauvoir (20 th century) and many others. Life has the meaning that the individual gives it. Right and wrong are determined by the individual. ‘Bad faith’ : Not making choices, not being responsible for our choices in situations is to act in bad faith. ‘Authenticity’ : Taking full responsibility for our choices, past and situations without blame, excuse, regret; taking responsibility for the world as it is. “I Heart Huckabees” - movie comedy that addresses many of themes of existentialism. Many fictional and dramatic representations by Sartre, Camus and De Beauvoir.

“We do not know what we want and yet we are responsible for what we are — that is the fact. ” “Life has no meaning a priori… It is up to you to give it a meaning, and value is nothing but the meaning that you choose. ” Jean Paul Sartre

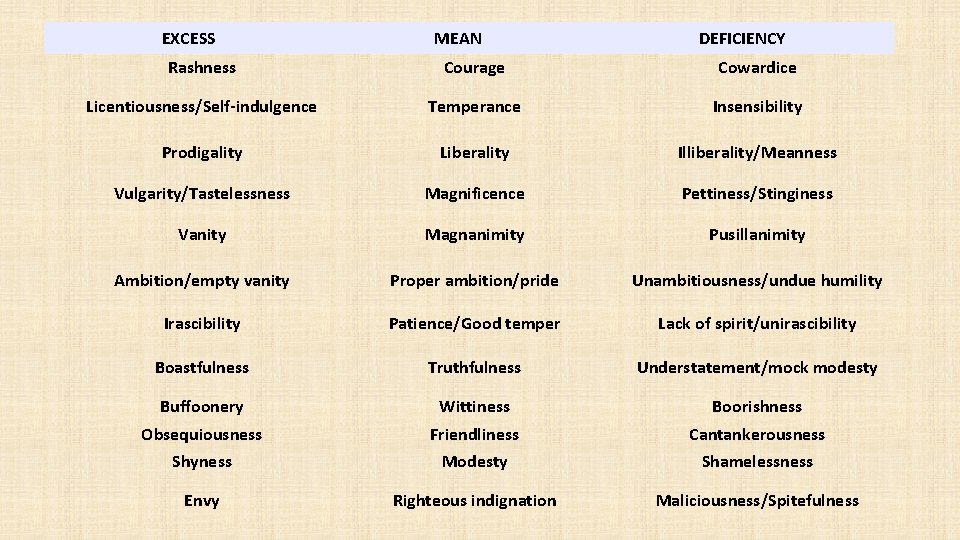

Virtue Ethics • Ancient theory of character formation as a foundation to ethical reasoning. If we aim at excellence (arête), we act ethically. • One develops character by emulating the virtues. • Aristotle in the West, Confucius in the East were major thinkers about character formation and virtue. • Aristotle in the Nicomachean Ethics (340 B. C. ); Confucius in the Analects (c. 450 to 350 B. C. ) • Aristotle’s Golden Mean • The extreme between two states of undesirable actions. • Example: Courage is the mean between cowardice and recklessness.

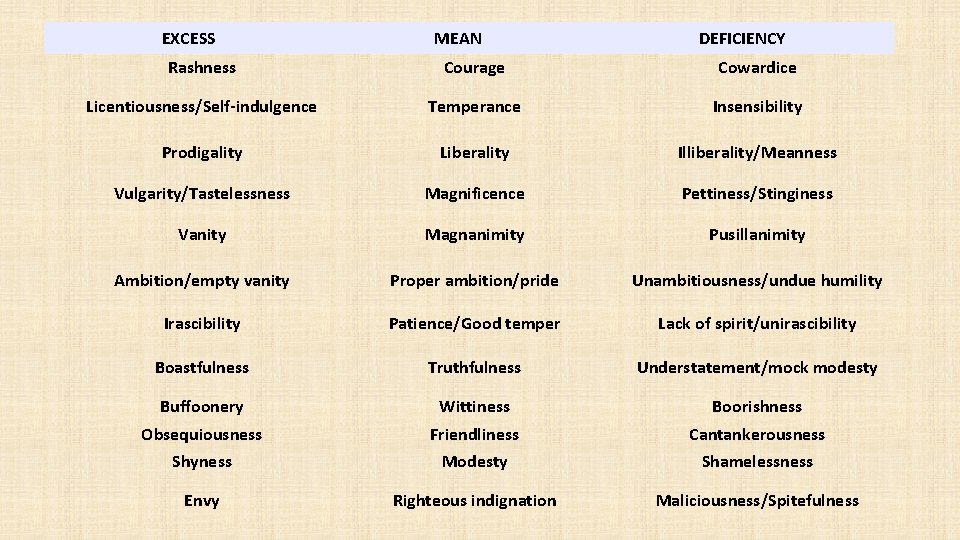

EXCESS MEAN DEFICIENCY Rashness Courage Cowardice Licentiousness/Self-indulgence Temperance Insensibility Prodigality Liberality Illiberality/Meanness Vulgarity/Tastelessness Magnificence Pettiness/Stinginess Vanity Magnanimity Pusillanimity Ambition/empty vanity Proper ambition/pride Unambitiousness/undue humility Irascibility Patience/Good temper Lack of spirit/unirascibility Boastfulness Truthfulness Understatement/mock modesty Buffoonery Wittiness Boorishness Obsequiousness Friendliness Cantankerousness Shyness Modesty Shamelessness Envy Righteous indignation Maliciousness/Spitefulness

• Virtue is acquired by practice. • As we practice the mean by considering excesses and deficiencies, we can acquire virtue or strength of character. • Virtue becomes “habitual. ” • Some of the ancients had “practice rooms” where they could rehearse frugality and deprivation.