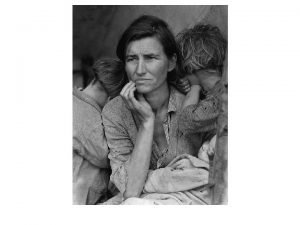

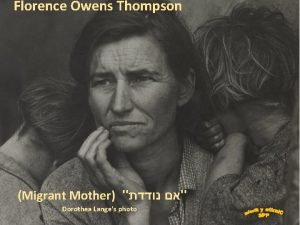

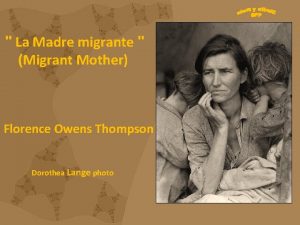

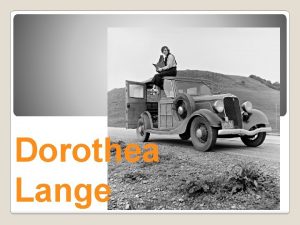

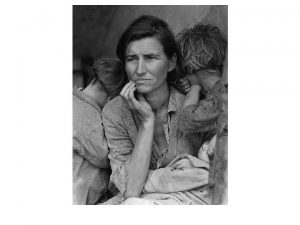

Dorothea Lange Destitute pea pickers in California Mother

- Slides: 14

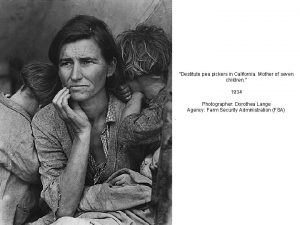

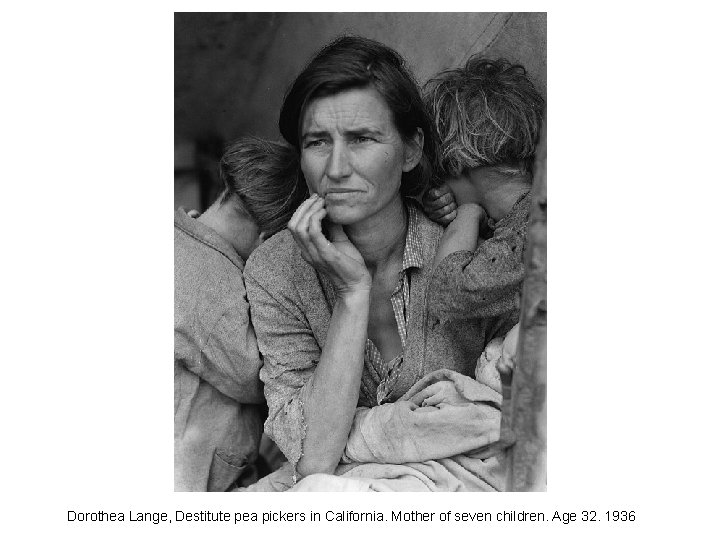

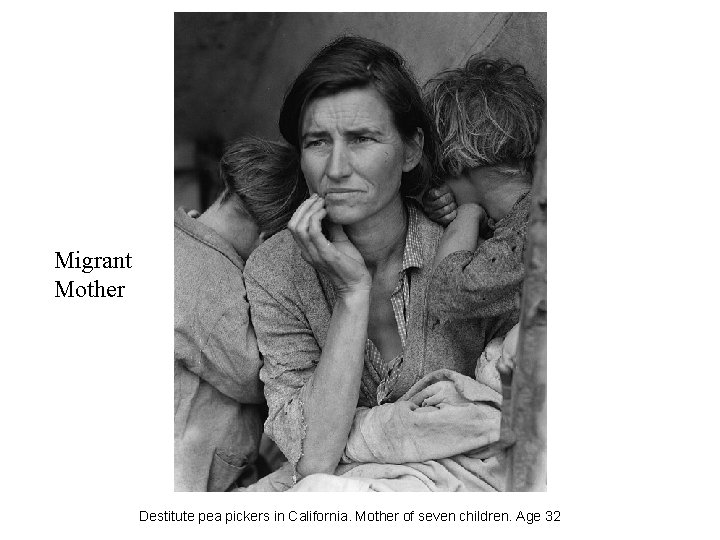

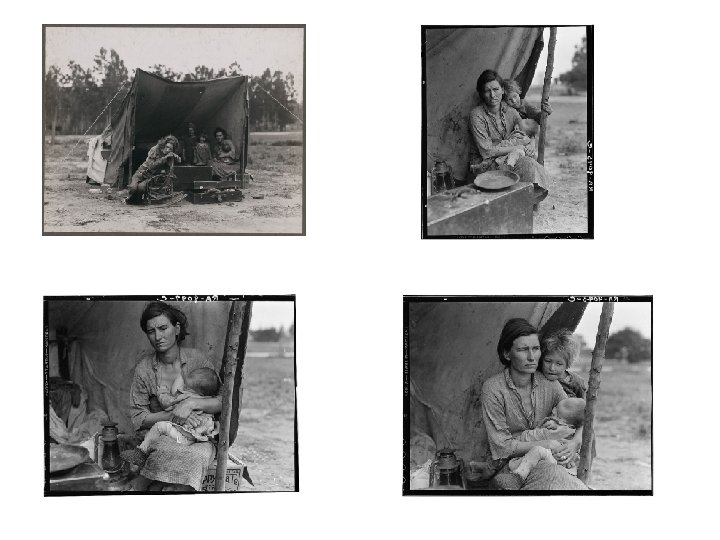

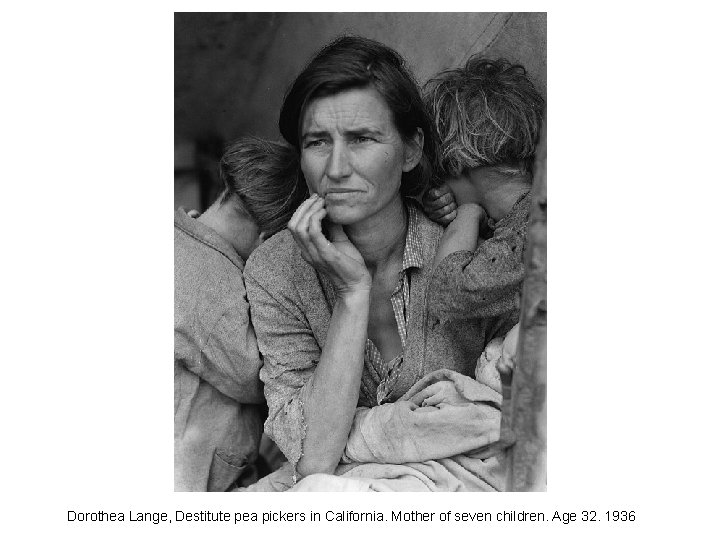

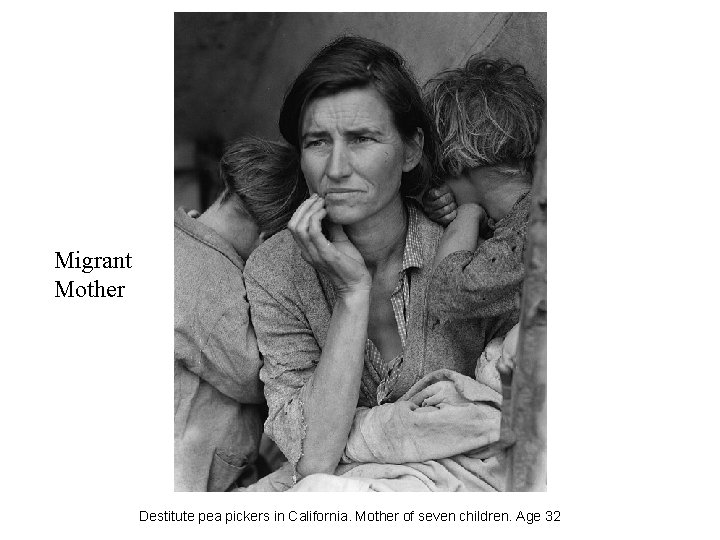

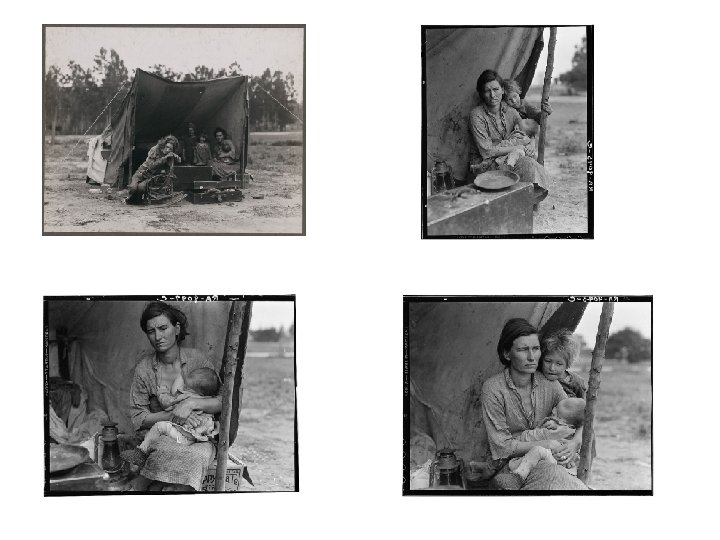

Dorothea Lange, Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age 32. 1936

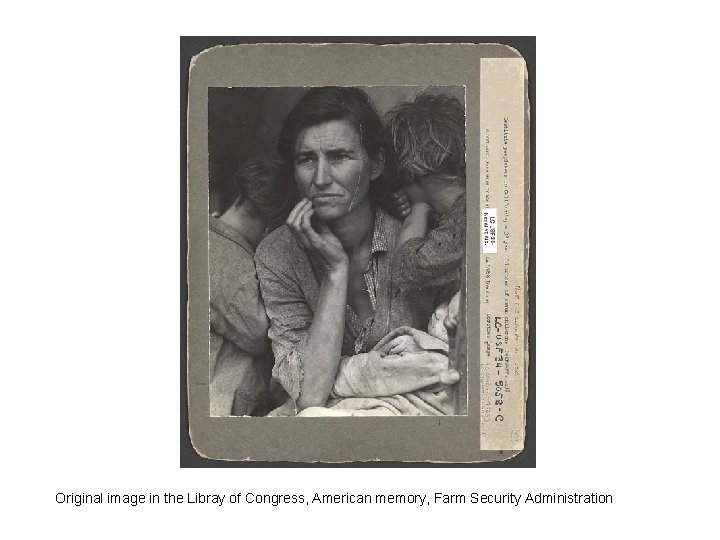

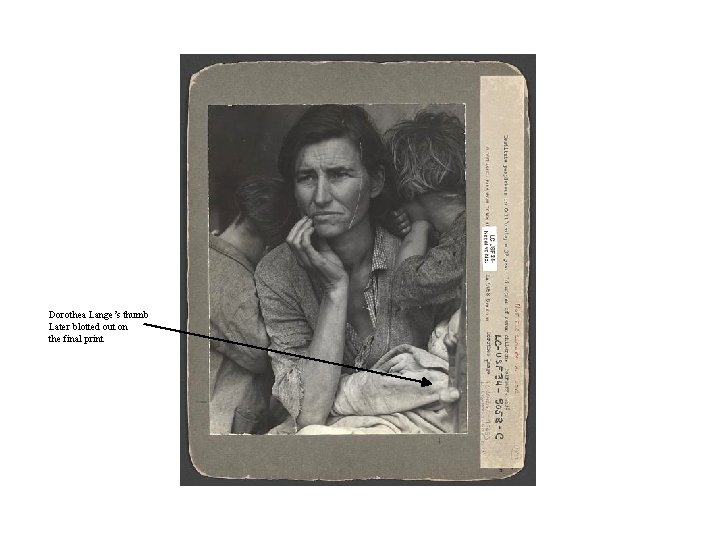

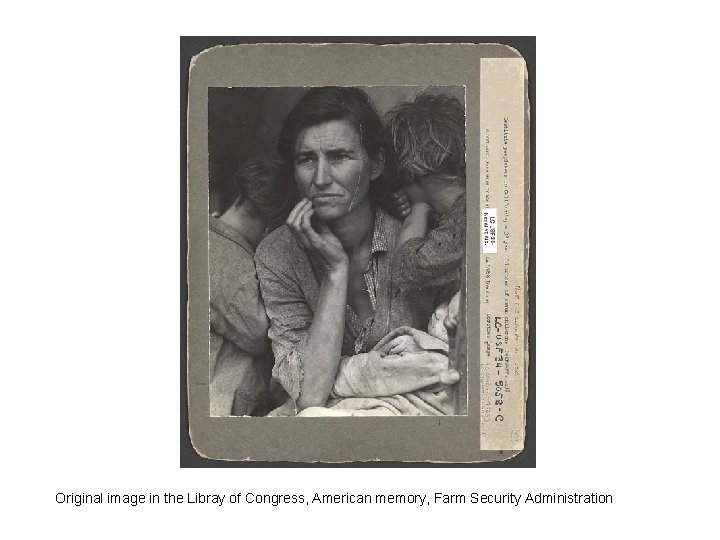

Original image in the Libray of Congress, American memory, Farm Security Administration

Migrant Mother Destitute pea pickers in California. Mother of seven children. Age 32

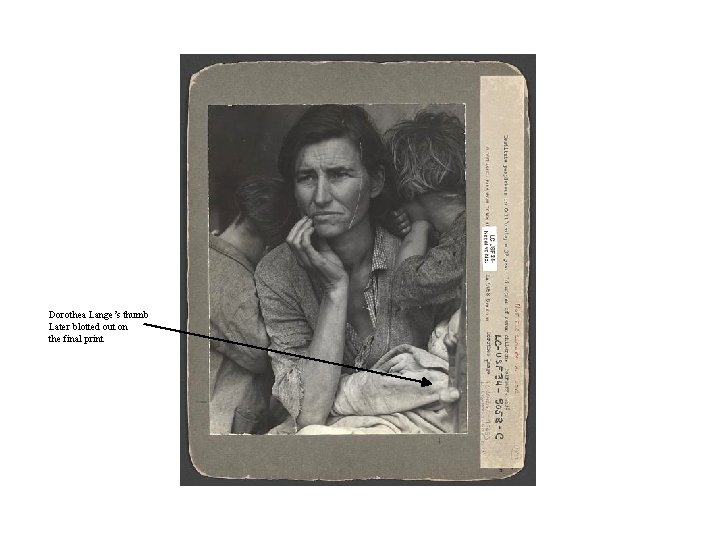

Dorothea Lange’s thumb Later blotted out on the final print

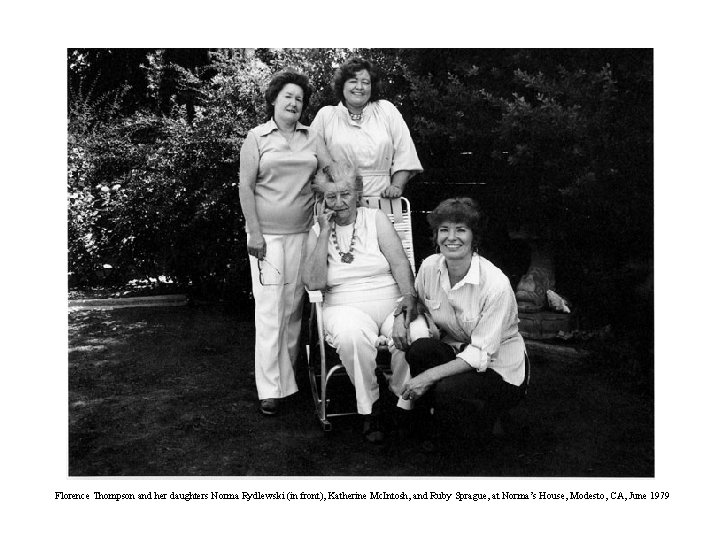

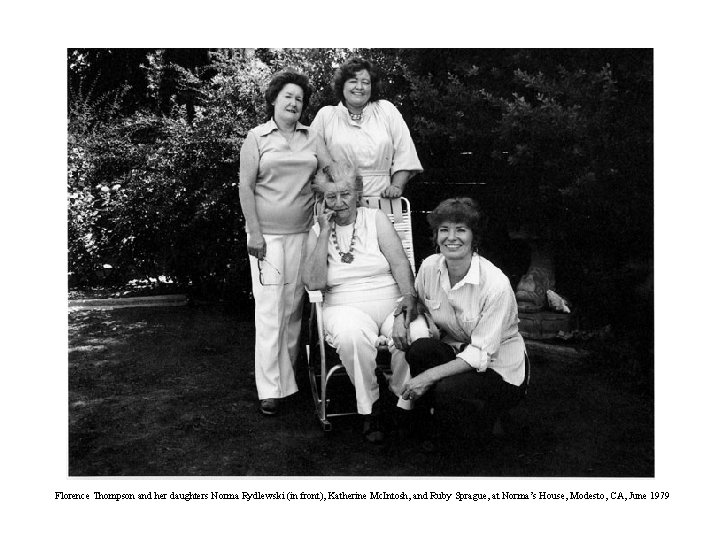

Florence Thompson and her daughters Norma Rydlewski (in front), Katherine Mc. Intosh, and Ruby Sprague, at Norma’s House, Modesto, CA, June 1979

Pour d’autres éléments sur Migrant Mother et d’autres images comparées 1936 -1980 : http: //ganzelgroup. com/books. html

« …le simple fait de rendre la réalité n’énonce rien quant à cette réalité. Une photo des usines Krupp ou de l’AEG ne révèle pas grand-chose sur ces institutions. La réalité proprement dite a glissé dans le fonctionnel. La réification des rapports humains, par exemple l’usine, ne révèle plus ce qui est en eux ultime. Il faut donc, en fait, construire quelque chose, quelque chose d’artificiel, de fabriqué. » Bertold Brecht cité par Walter Benjamin dans Petite histoire de la photographie

« La naissance, la mort ? Oui, ce sont des faits de nature, des faits universels. Mais si on leur ôte l’Histoire, il n’y a plus rien à en dire, le commentaire en devient purement tautologique ; l’échec de la photographie me paraît ici flagrant : redire la mort ou la naissance n’apprend, à la lettre, rien. Pour que ces faits naturels accèdent un langage véritable, il faut les insérer dans un ordre du savoir, c’està-dire postuler qu’on peut les transformer, soumettre précisément leur naturalité à notre critique d’hommes. » Roland Barthes, Mythologies, 1957

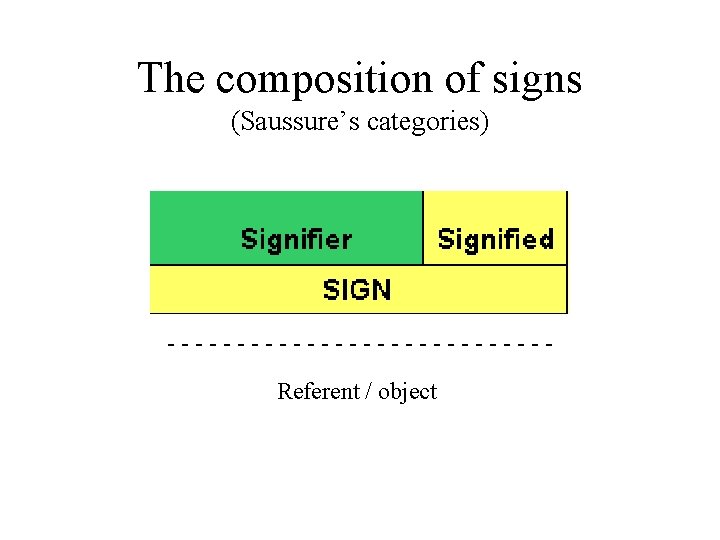

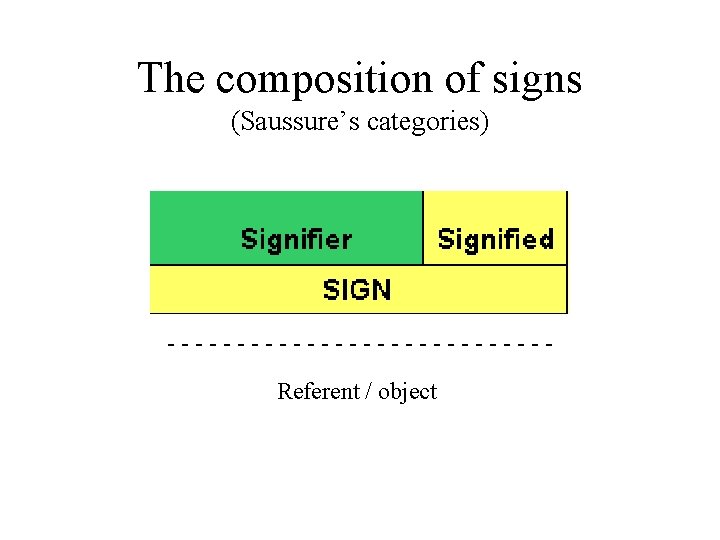

The composition of signs (Saussure’s categories) --------------Referent / object

La question des codes

Codes (from : http: //www. aber. ac. uk/media/Documents/S 4 B/sem 08. html In 1972 NASA sent into deep space an interstellar probe called Pioneer 10. It bore a golden plaque (see previous slide). The art historian Ernst Gombrich offers an insightful commentary on this: The National Aeronautics and Space Administration has equipped a deep-space probe with a pictorial message 'on the offchance that somewhere on the way it is intercepted by intelligent scientifically educated beings. ' It is unlikely that their effort was meant to be taken quite seriously, but what if we try? These beings would first of all have to be equipped with 'receivers' among their sense organs that respond to the same band of electromagnetic waves as our eyes do. Even in that unlikely case they could not possibly get the message. Reading an image, like the reception of any other message, is dependent on prior knowledge of possibilities; we can only recognize what we know. Even the sight of the awkward naked figures in the illustration cannot be separated in our mind from our knowledge. We know that feet are for standing and eyes are for looking and we project this knowledge onto these configurations, which would look 'like nothing on earth' without this prior information. It is this information alone that enables us to separate the code from the message; we see which of the lines are intended as contours and which are intended as conventional modelling. Our 'scientifically educated' fellow creatures in space might be forgiven if they saw the figures as wire constructs with loose bits and pieces hovering weightlessly in between. Even if they deciphered this aspect of the code, what would they make of the woman's right arm that tapers off like a flamingo's neck and beak? The creatures are 'drawn to scale against the outline of the spacecraft, ' but if the recipients are supposed to understand foreshortening, they might also expect to see perspective and conceive the craft as being further back, which would make the scale of the manikins minute. As for the fact that 'the man has his right hand raised in greeting' (the female of the species presumably being less outgoing), not even an earthly Chinese or Indian would be able to correctly interpret this gesture from his own repertory. The representation of humans is accompanied by a chart: a pattern of lines beside the figures standing for the 14 pulsars of the Milky Way, the whole being designed to locate the sun of our universe. A second drawing (how are they to know it is not part of the same chart? ) 'shows the earth and the other planets in relation to the sun and the path of Pioneer from earth and swinging past Jupiter. ' The trajectory, it will be noticed, is endowed with a directional arrowhead; it seems to have escaped the designers that this is a conventional symbol unknown to a race that never had the equivalent of bows and arrows. (Gombrich 1974, 255 -8; Gombrich 1982, 150 -151).

Norma rydlewski

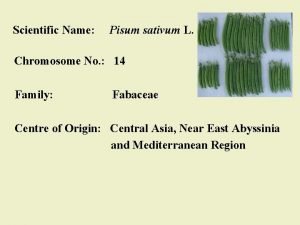

Norma rydlewski Palam triloki is a variety of

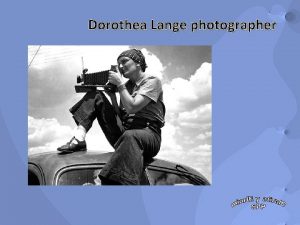

Palam triloki is a variety of Dorothea lange farm security administration

Dorothea lange farm security administration Land distribution meeting extremadura spain 1936

Land distribution meeting extremadura spain 1936 Dorothea lange jackson pollock

Dorothea lange jackson pollock Florence owens thompson norma rydlewski

Florence owens thompson norma rydlewski Dorothea lange photos

Dorothea lange photos Bull market apush

Bull market apush Dorothea lange manzanar

Dorothea lange manzanar Dorothea lange photos

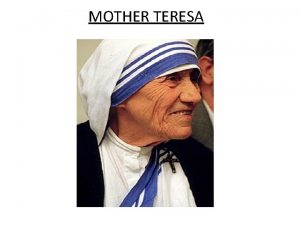

Dorothea lange photos Mother teresa poem

Mother teresa poem Bellerphon

Bellerphon Wie lange dauerte der hundertjährige krieg

Wie lange dauerte der hundertjährige krieg Yerkes dodson law

Yerkes dodson law James-lange theory

James-lange theory