Arthur Cecil Pigou 1877 1959 and John Maynard

![Keynes’s General Theory: Chapter 2 This [second postulate of Classical economics] is compatible with Keynes’s General Theory: Chapter 2 This [second postulate of Classical economics] is compatible with](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/9e4265b52495c2512590957a4ff5fbc4/image-17.jpg)

![Keynes’s General Theory: Chapter 2. . . [T]he contention that the unemployment which characterizes Keynes’s General Theory: Chapter 2. . . [T]he contention that the unemployment which characterizes](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/9e4265b52495c2512590957a4ff5fbc4/image-18.jpg)

![Keynes’s General Theory: Chapter 2 [The] fundamental objection, which we shall develop in the Keynes’s General Theory: Chapter 2 [The] fundamental objection, which we shall develop in the](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/9e4265b52495c2512590957a4ff5fbc4/image-20.jpg)

- Slides: 30

Arthur Cecil Pigou (1877 -1959) and John Maynard Keynes (1883 -1946)

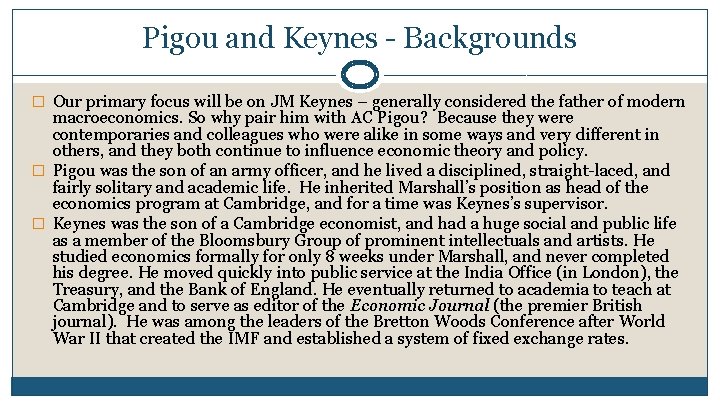

Pigou and Keynes - Backgrounds � Our primary focus will be on JM Keynes – generally considered the father of modern macroeconomics. So why pair him with AC Pigou? Because they were contemporaries and colleagues who were alike in some ways and very different in others, and they both continue to influence economic theory and policy. � Pigou was the son of an army officer, and he lived a disciplined, straight-laced, and fairly solitary and academic life. He inherited Marshall’s position as head of the economics program at Cambridge, and for a time was Keynes’s supervisor. � Keynes was the son of a Cambridge economist, and had a huge social and public life as a member of the Bloomsbury Group of prominent intellectuals and artists. He studied economics formally for only 8 weeks under Marshall, and never completed his degree. He moved quickly into public service at the India Office (in London), the Treasury, and the Bank of England. He eventually returned to academia to teach at Cambridge and to serve as editor of the Economic Journal (the premier British journal). He was among the leaders of the Bretton Woods Conference after World War II that created the IMF and established a system of fixed exchange rates.

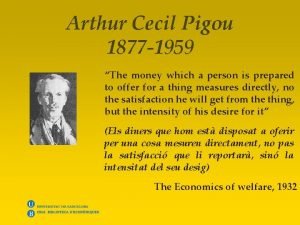

Pigou’s Contributions to Economics � Pigou, unlike Keynes, was generally content to build on the work of the British economists who preceded him. Thus, in the very first footnote of his book, The General Theory, Keynes said the following: “The classical economists” was a name invented by Marx to cover Ricardo and James Mill and their predecessors, that is to say for the founders of theory which culminated in the Ricardian economics. I have become accustomed, perhaps perpetrating a solecism, to include in “the classical school” the followers of Ricardo, those, that is to say, who adopted and perfected theory of the Ricardian economics, including (for example) J. S. Mill, Marshall, Edgeworth and Prof. Pigou. � So Keynes declared that his contemporary Pigou was writing in the Classical tradition of Smith, Say, Ricardo, Marshall – a tradition that Keynes was attempting to “escape. ” Still, Pigou made at least one important contribution to theory and policy that is remembered today…

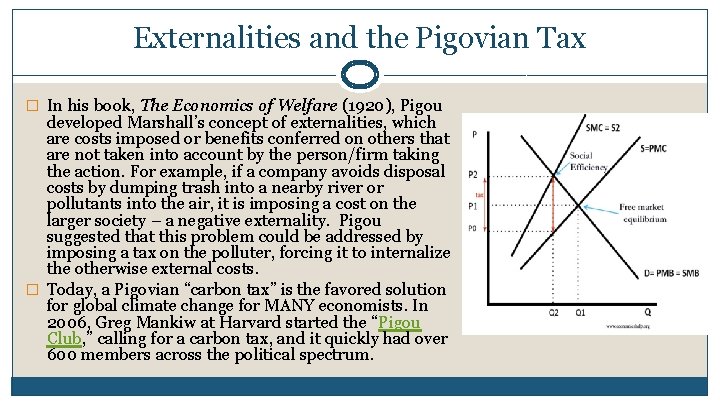

Externalities and the Pigovian Tax � In his book, The Economics of Welfare (1920), Pigou developed Marshall’s concept of externalities, which are costs imposed or benefits conferred on others that are not taken into account by the person/firm taking the action. For example, if a company avoids disposal costs by dumping trash into a nearby river or pollutants into the air, it is imposing a cost on the larger society – a negative externality. Pigou suggested that this problem could be addressed by imposing a tax on the polluter, forcing it to internalize the otherwise external costs. � Today, a Pigovian “carbon tax” is the favored solution for global climate change for MANY economists. In 2006, Greg Mankiw at Harvard started the “Pigou Club, ” calling for a carbon tax, and it quickly had over 600 members across the political spectrum.

Keynes and the Macro Focus � Keynes, it seems, never said much about the Pigovian tax or other topics in microeconomics, because his public service experience gave him a stronger interest in the macroeconomy. During WW I, he was involved in monetary affairs at the Treasury. After the war, he tried unsuccessfully to keep the victorious powers from imposing such heavy reparations costs on the Germans that it would cause social unrest and lead to another war. He also argued against the imposition of a gold standard in Britain, saying that it was unnecessarily depressing the economy – an argument that finally prevailed in 1931 after the outbreak of the Great Depression. � During the events above, Keynes had diminishing faith in the Classical orthodoxy he had learned from Marshall and Pigou at Cambridge – an orthodoxy based on Say’s Law, suggesting that the market system will always generate aggregate demand equal to any level of production and trend quickly toward full employment if there are no continuing obstacles or disruptions, such as wars, civil unrest, or excessive governmental controls. Keynes famously said that the market system may eventually correct itself in the long run, but “in the long run we’re all dead. ”

Keynes and the Macro Focus � Keynes, it seems, never said much about the Pigovian tax or other topics in microeconomics, because his public service experience gave him a stronger interest in the macroeconomy. During WW I, he was involved in monetary affairs at the Treasury. After the war, he tried unsuccessfully to keep the victorious powers from imposing such heavy reparations costs on the Germans that it would cause social unrest and lead to another war. He also argued against the imposition of a gold standard in Britain, saying that it was unnecessarily depressing the economy – an argument that finally prevailed in 1931 after the outbreak of the Great Depression. � During the events above, Keynes had diminishing faith in the Classical orthodoxy he had learned from Marshall and Pigou at Cambridge – an orthodoxy based on Say’s Law, suggesting that the market system will always generate aggregate demand equal to any level of production and trend quickly toward full employment if there are no continuing obstacles or disruptions, such as wars, civil unrest, or excessive governmental controls. Keynes famously said that the market system may eventually correct itself in the long run, but “in the long run we’re all dead. ”

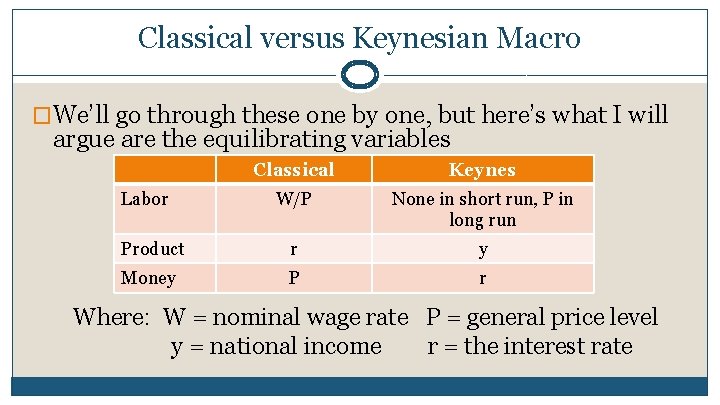

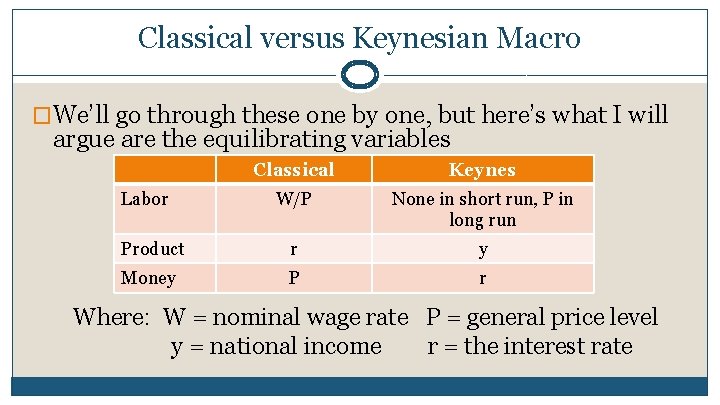

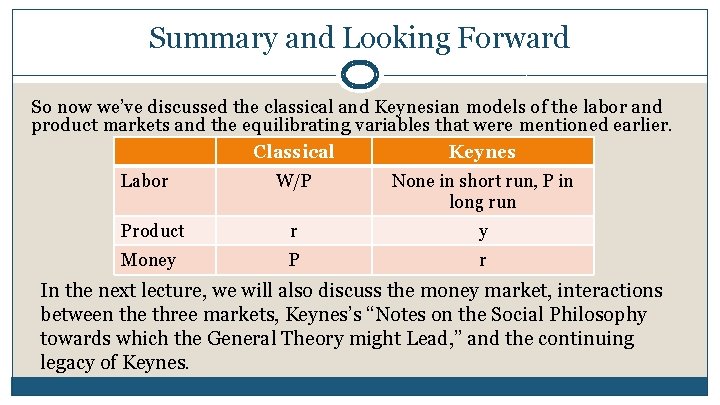

Classical versus Keynesian Macro �One way to think of the difference between Classical (long run) and Keynesian (short run) macroeconomics is to consider the equilibrating mechanisms in three major markets for labor, products, and money. In microeconomics, we say that if the quantities demanded and supplied of, say, corn are not equal to one another, they will be brought in line by changes in the price of corn (the equilibrating variable). So, what are the equilibrating variables for the macro labor, product, and money markets?

Classical versus Keynesian Macro �We’ll go through these one by one, but here’s what I will argue are the equilibrating variables Classical Keynes W/P None in short run, P in long run Product r y Money P r Labor Where: W = nominal wage rate P = general price level y = national income r = the interest rate

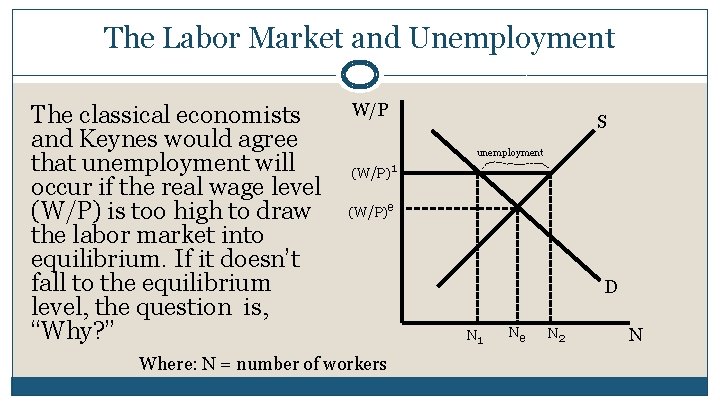

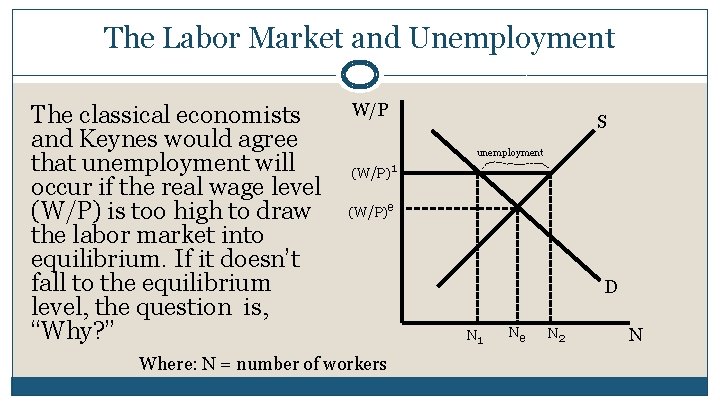

The Labor Market and Unemployment The classical economists and Keynes would agree that unemployment will occur if the real wage level (W/P) is too high to draw the labor market into equilibrium. If it doesn’t fall to the equilibrium level, the question is, “Why? ” W/P S unemployment (W/P)1 (W/P)e Where: N = number of workers D N 1 Ne N 2 N

The Labor Market and Unemployment � Keynes and the Classical authors have different answers to the question that was posed on the previous slide, but the difference between them has been misinterpreted in many (not all) textbooks, web pages, and other literature. Often, they have said (incorrectly) that the Classical authors believed the real wage would always fall quickly to the equilibrium level, so sustained unemployment would never happen. Keynes, they have said, was the guy who noted that nominal wages are “sticky” downward because of long-term union labor contracts, minimum-wage laws, and other institutions.

The Labor Market and Unemployment � Here a couple of online examples of the incorrect distinction that I noted on the previous side: “An innovation from Keynes was the concept of price stickiness – the recognition that in reality workers often refuse to lower their wage demands even in cases where a classical economist might argue it is rational for them to do so. https: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/John_Maynard_Keynes In establishing his theory of involuntary unemployment, Keynes rejected the classical assumption of wage-price flexibility. Money wages are rigid or inflexible in the downward direction… There are two reasons for wage inflexibility. First is the money illusion. Second is the institutional reason. Trade unions prevent wage rate from falling. Thus, any wage cut will be resisted. http: //www. economicsdiscussion. net/employment-theories/keynesian-theory-ofinvoluntary-unemployment-with-diagram/6209

The Labor Market and Unemployment �Why do I say that this is an incorrect distinction? First, because Pigou and other Classical authors were quite aware of the possibility that wage rigidity caused by union contracts and minimum-wage laws could cause long-term unemployment. Wage rigidities played a role in explaining unemployment in Pigou’s book, Unemployment (1914) and he noted that this problem had grown more serious in his Theory of Unemployment (1933, published 2 years before Keynes’s General Theory).

Pigou on Wages and Unemployment � Here’s what Pigou said on pp. 255 -256 of his Theory of Unemployment (1933, published 2 years before Keynes’s General Theory): � “Students of our problem in this country before [World War I], while recognizing maladjustments of a long-run character associated with wage policy as one of the factors responsible for unemployment, in general took the view that the part played by them was small. Unemployment, for these writers, was, in the main, a function of industrial fluctuations and labor immobility — of short-run frictions rather than of long-run tendencies… Since the post-Armistice boom, however, the unemployment situation has been very different… Instead of a percentage of unemployment amounting… to some 4. 5 per cent, post-war unemployment has moved about a mean from twice to three times as large as this. This circumstance suggests strongly that the goal of long-run tendencies in recent times has been a wage level substantially above that proper to nil unemployment, and that a substantial part of post-war unemployment is attributable to that fact… Wage policy as a possible long-run determinant of unemployment calls, therefore, at the present time, for closer study than would have been thought necessary twenty years ago. ” � So Pigou and the other Classical economists knew that wage rigidities could, and sometimes did, cause prolonged bouts of unemployment. So how was Keynes different?

Keynes’s General Theory: Preface � THIS book is chiefly addressed to my fellow economists. I hope that it will be intelligible to others. But its main purpose is to deal with difficult questions of theory, and only in the second place with the applications of this theory to practice. . . Those, who are strongly wedded to what I shall call “the classical theory”, will fluctuate, I expect, between a belief that I am quite wrong and a belief that I am saying nothing new. . . � This book. . . has evolved into what is primarily a study of the forces which determine changes in the scale of output and employment as a whole; and, whilst it is found that money enters into the economic scheme in an essential and peculiar manner, technical monetary detail falls into the background. A monetary economy, we shall find, is essentially one in which changing views about the future are capable of influencing the quantity of employment and not merely its direction. . . We are thus led to a more general theory, which includes the classical theory with which we are familiar, as a special case. . . � The composition of this book has been for the author a long struggle of escape, and so must the reading of it be for most readers if the author’s assault upon them is to be successful, — a struggle of escape from habitual modes of thought and expression. The ideas which are here expressed so laboriously are extremely simple and should be obvious. The difficulty lies, not in the new ideas, but in escaping from the old ones, which ramify, for those brought up as most of us have been, into every corner of our minds.

Keynes’s General Theory: Chapter 2 Introduction � MOST treatises on theory of value and production are primarily concerned with the distribution of a given volume of employed resources between different uses and with the conditions which, assuming the employment of this quantity of resources, determine their relative rewards and the relative values of their products. � The question, also, of the volume of the available resources, in the sense of the size of the employable population, the extent of natural wealth and the accumulated capital equipment, has often been treated descriptively. But the pure theory of what determines the actual employment of the available resources has seldom been examined in great detail. To say that it has not been examined at all would, of course, be absurd. For every discussion concerning fluctuations of employment, of which there have been many, has been concerned with it. I mean, not that the topic has been overlooked, but that the fundamental theory underlying it has been deemed so simple and obvious that it has received, at the most, a bare mention. � [Clearly a reflection on Ricardian economics, focusing on distribution and value]

Keynes’s General Theory: Chapter 2 � The Postulates of the Classical Economics � The classical theory of employment — supposedly simple and obvious — has been based. I think, � � � on two fundamental postulates, though practically without discussion, namely: i. The wage is equal to the marginal product of labour That is to say, the wage of an employed person is equal to the value which would be lost if employment were to be reduced by one unit (after deducting any other costs which this reduction of output would avoid); subject, however, to the qualification that the equality may be disturbed, in accordance with certain principles, if competition and markets are imperfect. ii. The utility of the wage when a given volume of labour is employed is equal to the marginal disutility of that amount of employment. That is to say, the real wage of an employed person is that which is just sufficient (in the estimation of the employed persons themselves) to induce the volume of labour actually employed to be forthcoming… [So the demand for labor is determined by marginal productivity (employers will want to hire more workers when the value of their marginal is higher than the wage), and the supply of labor is explained by Jevons’s theory of utility maximization that we studied. ]

![Keyness General Theory Chapter 2 This second postulate of Classical economics is compatible with Keynes’s General Theory: Chapter 2 This [second postulate of Classical economics] is compatible with](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/9e4265b52495c2512590957a4ff5fbc4/image-17.jpg)

Keynes’s General Theory: Chapter 2 This [second postulate of Classical economics] is compatible with what may be called ‘frictional’ unemployment. For a realistic interpretation of it legitimately allows for various inexactnesses of adjustment which stand in the way of continuous full employment: for example, unemployment due to … the fact that the change-over from one employment to another cannot be effected without a certain delay, so that there will always exist … resources unemployed ‘between jobs’. In addition to ‘frictional’ unemployment, the postulate is also compatible with ‘voluntary’ unemployment due to the refusal or inability of a unit of labor, as a result of legislation or social practices or of combination for collective bargaining or of slow response to change or of mere human obstinacy, to accept a reward corresponding to the value of the product attributable to its marginal productivity. But these two categories of ‘frictional’ unemployment and ‘voluntary’ unemployment are comprehensive. The classical postulates do not admit of the possibility of the third category, which I shall define below as ‘involuntary’ unemployment. � [So Keynes acknowledged that the Classical authors were aware of unemployment caused by institutional wage inflexibility – but that’s voluntary. His contribution would be to explain the source of involuntary unemployment]

![Keyness General Theory Chapter 2 The contention that the unemployment which characterizes Keynes’s General Theory: Chapter 2. . . [T]he contention that the unemployment which characterizes](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/9e4265b52495c2512590957a4ff5fbc4/image-18.jpg)

Keynes’s General Theory: Chapter 2. . . [T]he contention that the unemployment which characterizes a depression is due to a refusal by labor to accept a reduction of moneywages is not clearly supported by the facts. It is not very plausible to assert that unemployment in the United States in 1932 was due either to labor obstinately refusing to accept a reduction of money-wages or to its obstinately demanding a real wage beyond what the productivity of the economic machine was capable of furnishing wide variations are experienced in the volume of employment without any apparent change either in the minimum real demands of labor or in its productivity. Labor is not more truculent in the depression than in the boom — far from it. Nor is its physical productivity less. These facts from experience are a prima facie ground for questioning the adequacy of the classical analysis. . .

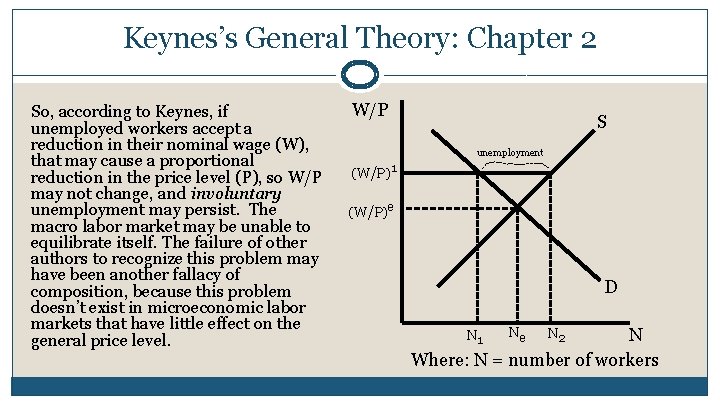

Keynes’s General Theory: Chapter 2 But there is a more fundamental objection. The second postulate flows from the idea that the real wages of labor depend on the wage bargains which labor makes with the entrepreneurs… The traditional theory maintains, in short, that the wage bargains between the entrepreneurs and the workers determine the real wage… Now the assumption that the general level of real wages depends on the money-wage bargains between the employers and the workers is not obviously true. Indeed it is strange that so little attempt should have been made to prove or to refute it. For it is far from being consistent with the general tenor of the classical theory, which has taught us to believe that prices are governed by marginal prime cost in terms of money and that money -wages largely govern marginal prime cost. Thus if money-wages change, one would have expected the classical school to argue that prices would change in almost the same proportion, leaving the real wage and the level of unemployment practically the same as before. . .

![Keyness General Theory Chapter 2 The fundamental objection which we shall develop in the Keynes’s General Theory: Chapter 2 [The] fundamental objection, which we shall develop in the](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/9e4265b52495c2512590957a4ff5fbc4/image-20.jpg)

Keynes’s General Theory: Chapter 2 [The] fundamental objection, which we shall develop in the ensuing chapters, flows from our disputing the assumption that the general level of real wages is directly determined by the character of the wage bargain. In assuming that the wage bargain determines the real wage the classical school have slipt in an illicit assumption. For there may be no method available to labor as a whole whereby it can bring the general level of moneywages into conformity with the marginal disutility of the current volume of employment. There may exist no expedient by which labor as a whole can reduce its real wage to a given figure by making revised money bargains with the entrepreneurs. This will be our contention. . .

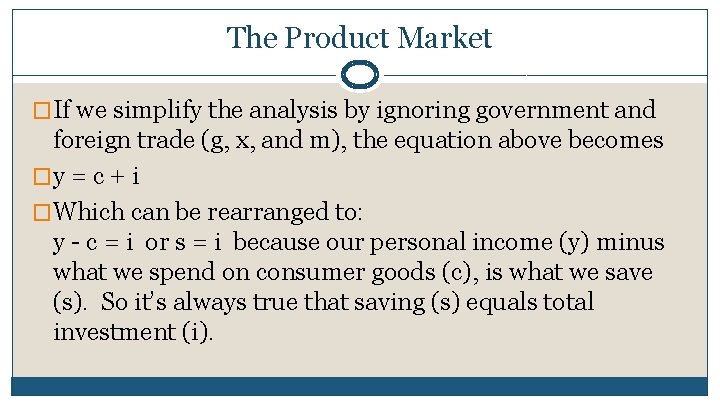

Keynes’s General Theory: Chapter 2 So, according to Keynes, if unemployed workers accept a reduction in their nominal wage (W), that may cause a proportional reduction in the price level (P), so W/P may not change, and involuntary unemployment may persist. The macro labor market may be unable to equilibrate itself. The failure of other authors to recognize this problem may have been another fallacy of composition, because this problem doesn’t exist in microeconomic labor markets that have little effect on the general price level. W/P S unemployment (W/P)1 (W/P)e D Ne N Where: N = number of workers N 1 N 2

The Product Market � Now, moving from the labor market to the product market, we begin with the formula for national income and product and the components of demand: � y = c + i + g + (x-m) � Where y = national income and product c = consumer purchases i = investment g = government purchases x = exports m = imports which just says that everything that is produced (y) ends up in somebody’s possession.

The Product Market �If we simplify the analysis by ignoring government and foreign trade (g, x, and m), the equation above becomes �y = c + i �Which can be rearranged to: y - c = i or s = i because our personal income (y) minus what we spend on consumer goods (c), is what we save (s). So it’s always true that saving (s) equals total investment (i).

The Product Market � However, total investment (i) has several components. Important for our purposes, part of investment is intended, and part is often unintended. Companies intentionally invest in plant and equipment and families intentionally invest in houses. If a company willingly increases its stock of inventories to serve its customers better, that’s also a form of intentional investment. However, if a company’s sales fall short of expectations, and it “gets stuck” with additional inventories that it didn’t intend to accumulate, that’s called “unintended investment in inventories. ” Conversely, if sales are better than expected, the company may experience “unintended disinvestment in inventories. ” If companies are unintentionally gaining or losing inventories, they are likely to take corrective action, so we will say the product market is not in equilibrium. If unintentional investment is zero, and businesses are operating according to plan, we’ll say the product market is in equilibrium.

The Product Market �Once again, s = i or s = ii + iu (intended +unintended investment) �In equilibrium, iu = 0 or s = ii Also note that iu = s - ii , so iu will be positive (there will be unintended investment in inventories) if s > ii �So, for the product market, the question is, according to the Classics and Keynes, if s ≠ ii , what will draw them into equality?

The Classical Product Market The Classical idea of the product markets was based on Say’s Law, which Keynes summarized with the phrase, “supply creates its own demand. ” If goods are produced in the right proportions to one another, the market will adjust to ensure that any volume of goods can be bought. If I produce goods, I will want to quickly sell them, and I will typically use the proceeds to buy other goods. If I save part of the proceeds, my savings will be loaned to somebody else who wants to buy goods, and the interest rate will adjust to insure that my willingness to loan is matched by the willingness of others to borrow and spend. So, in the end, the full value of production will be converted into a demand for goods, and production can grow without interruption.

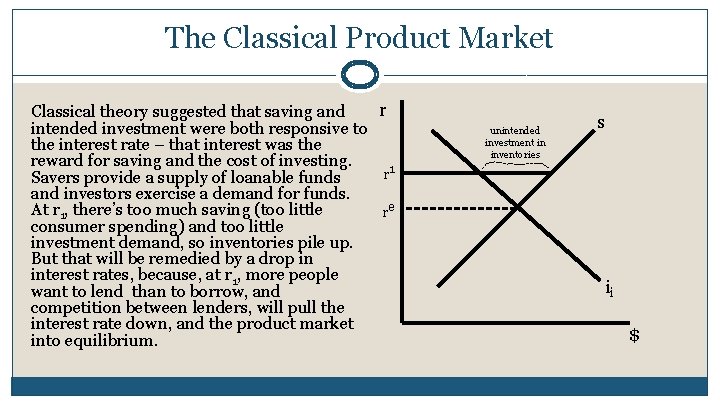

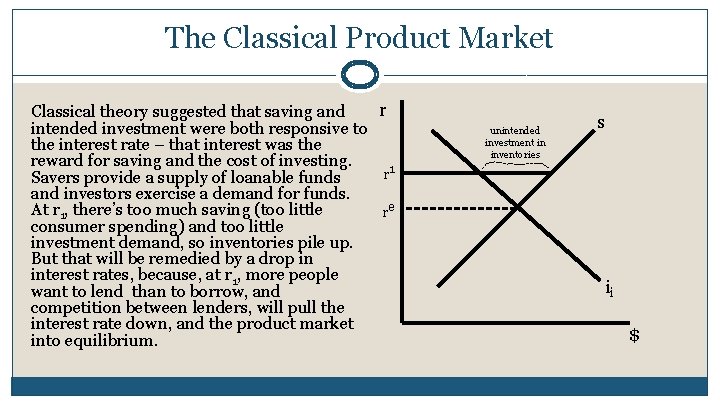

The Classical Product Market r Classical theory suggested that saving and intended investment were both responsive to the interest rate – that interest was the reward for saving and the cost of investing. r 1 Savers provide a supply of loanable funds and investors exercise a demand for funds. At r 1, there’s too much saving (too little re consumer spending) and too little investment demand, so inventories pile up. But that will be remedied by a drop in interest rates, because, at r 1, more people want to lend than to borrow, and competition between lenders, will pull the interest rate down, and the product market into equilibrium. unintended investment in inventories s ii $

Keynes’s Critique of Classical Product Market Theory � Keynes argued that the interest rate didn’t have sufficient power over intended investment to draw it into equality with saving. It has been supposed that any individual act of abstaining from consumption necessarily leads to, and amounts to the same thing as, causing the labor and commodities thus released from supplying consumption to be invested in the production of capital wealth. . . Those who think in this way are deceived, nevertheless, by an optical illusion, which makes two essentially different activities appear to be the same. They are fallaciously supposing that there is a nexus which unites decisions to abstain from present consumption with decisions to provide for future consumption; whereas the motives which determine the latter are not linked in any simple way with the motives which determine the former. . . � Investment is driven, Keynes said, by the “animal spirits” or the optimism/pessimism of investors who must make decisions today without knowing the future. I will not borrow money today, even at a zero interest rate, to build a factory if I am fearful that an impending recession will make it impossible to sell the output of the factory.

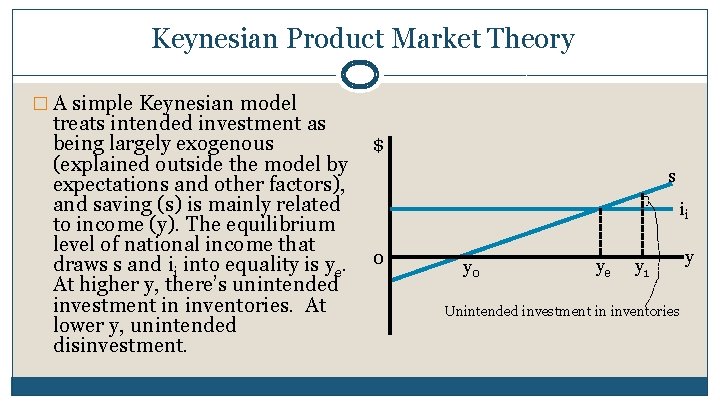

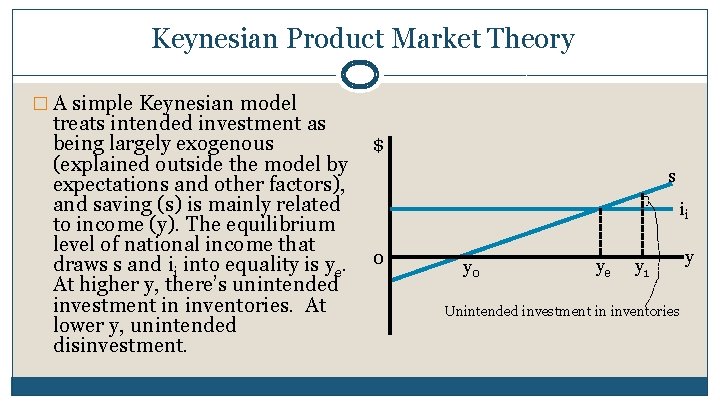

Keynesian Product Market Theory � A simple Keynesian model treats intended investment as being largely exogenous (explained outside the model by expectations and other factors), and saving (s) is mainly related to income (y). The equilibrium level of national income that draws s and ii into equality is ye. At higher y, there’s unintended investment in inventories. At lower y, unintended disinvestment. $ s ii 0 ye y 1 Unintended investment in inventories y

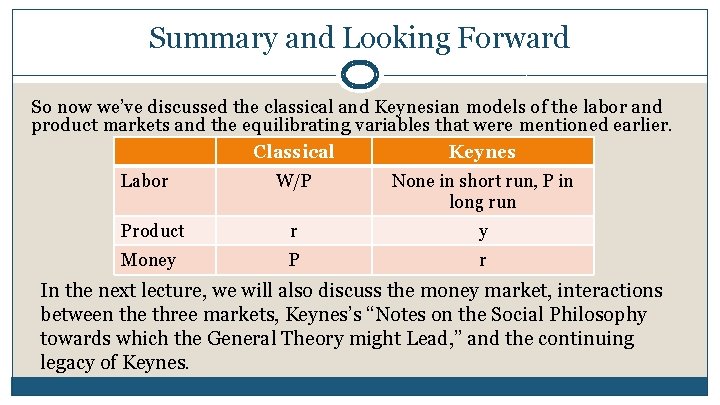

Summary and Looking Forward So now we’ve discussed the classical and Keynesian models of the labor and product markets and the equilibrating variables that were mentioned earlier. Classical Keynes W/P None in short run, P in long run Product r y Money P r Labor In the next lecture, we will also discuss the money market, interactions between the three markets, Keynes’s “Notes on the Social Philosophy towards which the General Theory might Lead, ” and the continuing legacy of Keynes.

Meritorische güter

Meritorische güter Pigou féle adó

Pigou féle adó Principle of maximum social advantage

Principle of maximum social advantage Musgrave maximum social advantage

Musgrave maximum social advantage Pigou féle adó

Pigou féle adó Economia del bienestar pigou

Economia del bienestar pigou Albany movement

Albany movement John arthur singer

John arthur singer Interdependenztheorie

Interdependenztheorie Richard emerson social exchange theory

Richard emerson social exchange theory John thibaut dan harold kelley

John thibaut dan harold kelley 1877 to 1918 cloze notes

1877 to 1918 cloze notes Compromise of 1877 apush

Compromise of 1877 apush Anthony comstock apush

Anthony comstock apush Compromise of 1877

Compromise of 1877 Gilded age labor strikes

Gilded age labor strikes Whats the compromise of 1877

Whats the compromise of 1877 Whats the compromise of 1877

Whats the compromise of 1877 1877 golden 1

1877 golden 1 Tanssija 1877-1927

Tanssija 1877-1927 Reconstruction art definition

Reconstruction art definition The gilded age 1877 to 1898 worksheet answers

The gilded age 1877 to 1898 worksheet answers 1894 railroad strike

1894 railroad strike The key tradeoff featured in the compromise of 1877

The key tradeoff featured in the compromise of 1877 Dissolved oxygen and chlorine molecules act as

Dissolved oxygen and chlorine molecules act as Cecil rhodes

Cecil rhodes Triada de cecil gray

Triada de cecil gray A hard frost diction

A hard frost diction Francis cecil sumner

Francis cecil sumner The british octopus cartoon meaning

The british octopus cartoon meaning Cecil rhodes political cartoon

Cecil rhodes political cartoon