WHAT ARE CONCORDANCES AND HOW ARE THEY USED

- Slides: 21

WHAT ARE CONCORDANCES AND HOW ARE THEY USED? C. Tribble

CONCORDANCE • A concordance is a collection of the occurrences of a word-form, each in its own textual environment. In its simplest form it is an index. Each wordform is indexed and a reference is given to the place of occurrence in a text. (Sinclair 1991: 32)

WORD-FORMS AND LEMMAS • Tokens : All the running words in the corpus • Word-forms = Type E. g. The verb to give has the forms give, gives, given, gave, giving, and to give. In other languages, the range of forms can be ten or more, and even hundreds • Lemma: the composite set of word-forms is called the lemma, e. g. GIVE.

WORD-FORMS AND LEMMAS • Typing all the word-forms you wish to find is to use the wild -card facility (regular expression in UNIX environments) which different concordancing programs offer. • A wild-card is a symbol which can be used to stand for one or many alpha-numeric characters. • To remember is that wildcard searches will usually produce a mix of wanted and unwanted results, especially in an unmarked-up corpus. Thus the search string cat* will give you cat and cats, but it also produces catch.

READING CONCORDANCES • Sinclair (2003: xvi–xvii) proposes a seven-stage procedure for working with concordance data. • Find all instances of ‘(19**) NOT in the context of ‘*. ’ 5 word-forms to the right [i. e. search for all dates included in round brackets that are NOT at the ends of sentences and which are therefore more likely to be associated with sentence integral citation forms]

STEP 1: INITIATE • This is a process of looking for patterns to the right or left of the node which have some kind of prominence, and which may be worth focusing on in order to assess their possible salience to the analysis in question (Figure 13. 17). • At the initiate stage in an analysis of this data you may first notice that there is a major pattern of SURNAME + (DATE).

STEP 2 INTERPRET Sinclair comments for this stage: • Look at the repeated words, and try to form a hypothesis that may link them or most of them. For example, they may be from the same word class, or they may have similar meanings. (Sinclair 2003: xvi) • In the present context, an initial working hypothesis could be: In academic writing, a pattern SURNAME + (DATE) is used to represent published work to which a reference is being made. Neither first name nor initials are used. Base pattern SURNAME (DATE)

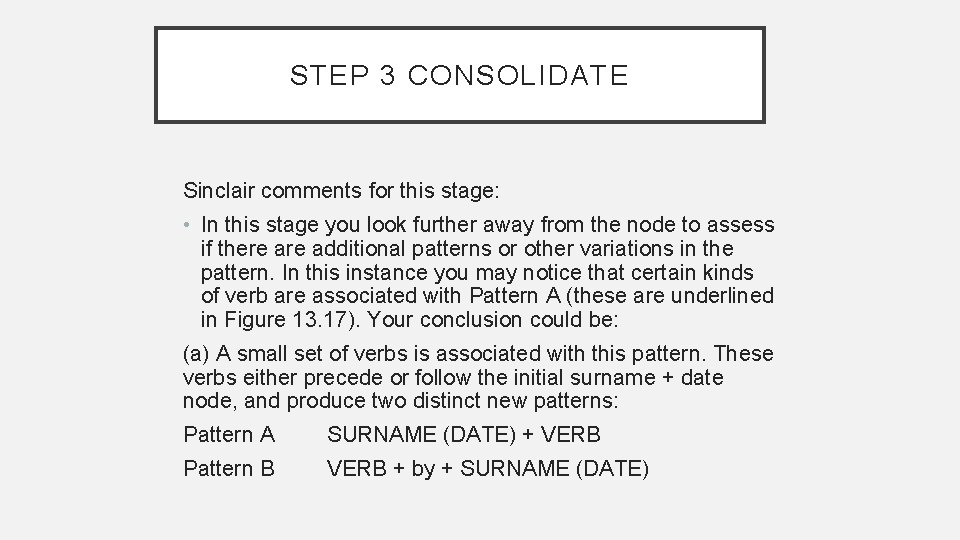

STEP 3 CONSOLIDATE Sinclair comments for this stage: • In this stage you look further away from the node to assess if there additional patterns or other variations in the pattern. In this instance you may notice that certain kinds of verb are associated with Pattern A (these are underlined in Figure 13. 17). Your conclusion could be: (a) A small set of verbs is associated with this pattern. These verbs either precede or follow the initial surname + date node, and produce two distinct new patterns: Pattern A SURNAME (DATE) + VERB Pattern B VERB + by + SURNAME (DATE)

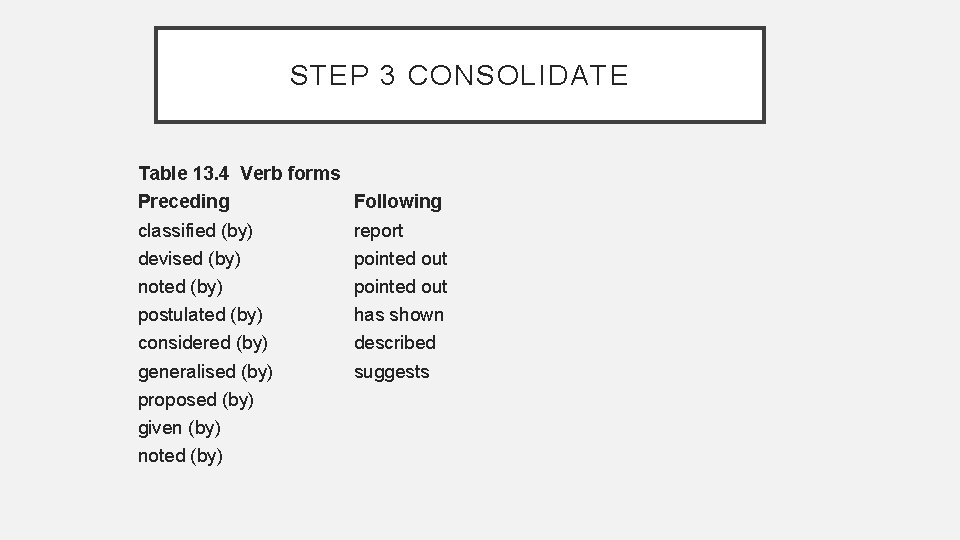

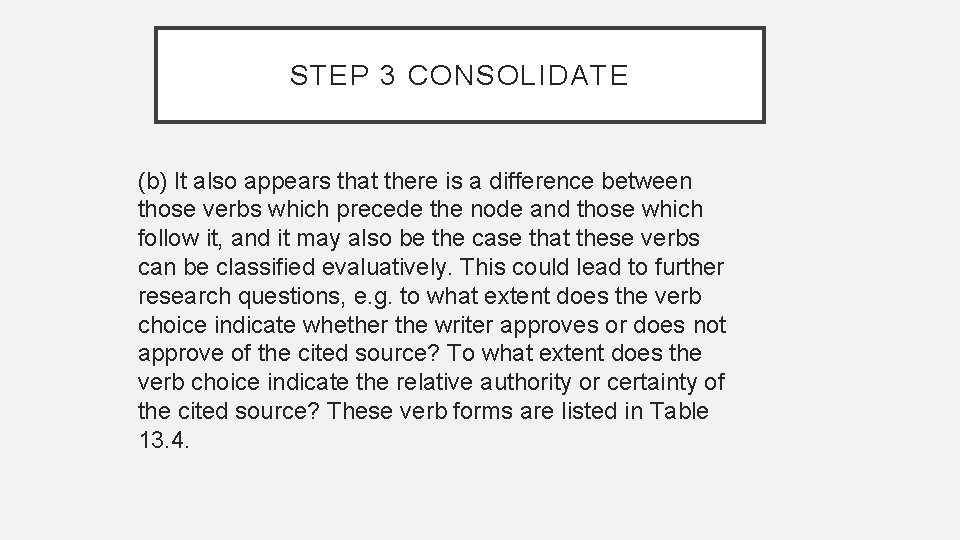

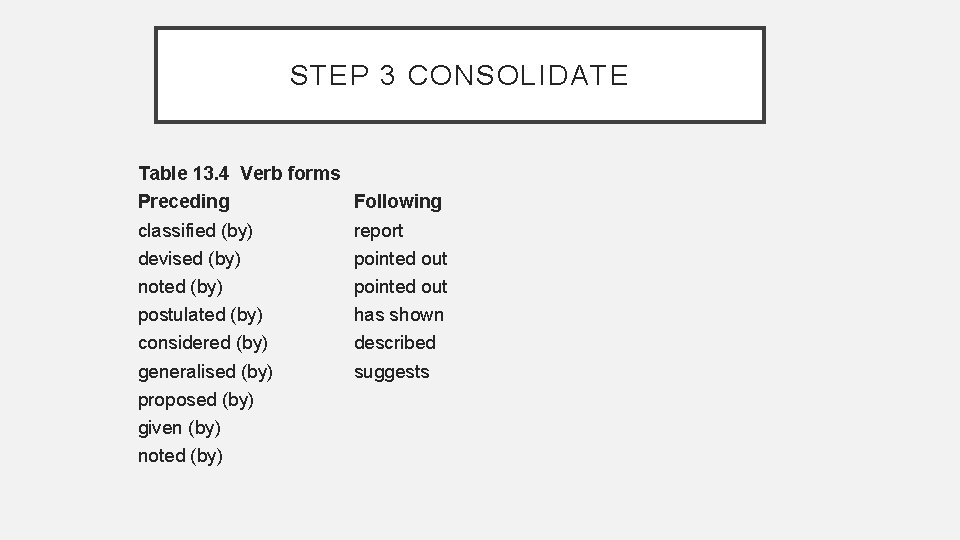

STEP 3 CONSOLIDATE (b) It also appears that there is a difference between those verbs which precede the node and those which follow it, and it may also be the case that these verbs can be classified evaluatively. This could lead to further research questions, e. g. to what extent does the verb choice indicate whether the writer approves or does not approve of the cited source? To what extent does the verb choice indicate the relative authority or certainty of the cited source? These verb forms are listed in Table 13. 4.

STEP 3 CONSOLIDATE Table 13. 4 Verb forms Preceding classified (by) devised (by) noted (by) postulated (by) considered (by) generalised (by) proposed (by) given (by) noted (by) Following report pointed out has shown described suggests

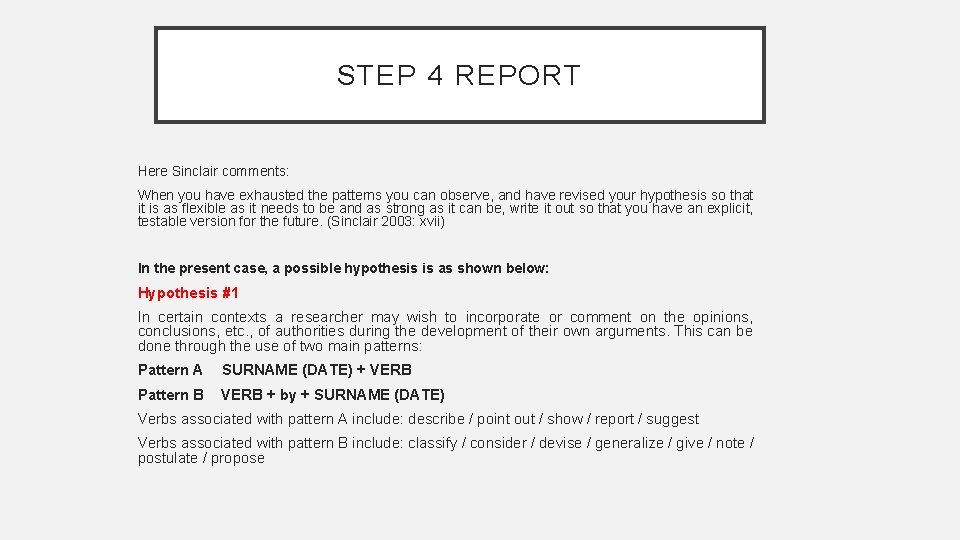

STEP 4 REPORT Here Sinclair comments: When you have exhausted the patterns you can observe, and have revised your hypothesis so that it is as flexible as it needs to be and as strong as it can be, write it out so that you have an explicit, testable version for the future. (Sinclair 2003: xvii) In the present case, a possible hypothesis is as shown below: Hypothesis #1 In certain contexts a researcher may wish to incorporate or comment on the opinions, conclusions, etc. , of authorities during the development of their own arguments. This can be done through the use of two main patterns: Pattern A SURNAME (DATE) + VERB Pattern B VERB + by + SURNAME (DATE) Verbs associated with pattern A include: describe / point out / show / report / suggest Verbs associated with pattern B include: classify / consider / devise / generalize / give / note / postulate / propose

STEP 5 RECYCLE This stage involves a further rigorous consideration of the extended contexts in which the node is found. This could lead to the discovery that evaluation or other comment on the authority cited may be shown through additional structures (Table 13. 6). This produces two further patterns: Pattern C ADVERBIAL [*] + SURNAME + (DATE) Pattern D VERB + by + SURNAME + (DATE) + VERB + TO INFINITIVE + EVALUATIVE ADJECTIVE

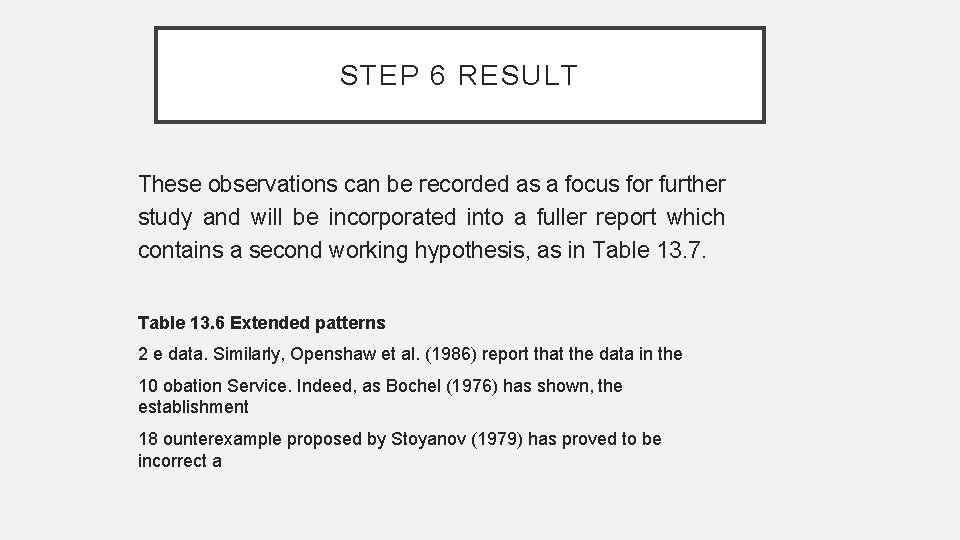

STEP 6 RESULT These observations can be recorded as a focus for further study and will be incorporated into a fuller report which contains a second working hypothesis, as in Table 13. 7. Table 13. 6 Extended patterns 2 e data. Similarly, Openshaw et al. (1986) report that the data in the 10 obation Service. Indeed, as Bochel (1976) has shown, the establishment 18 ounterexample proposed by Stoyanov (1979) has proved to be incorrect a

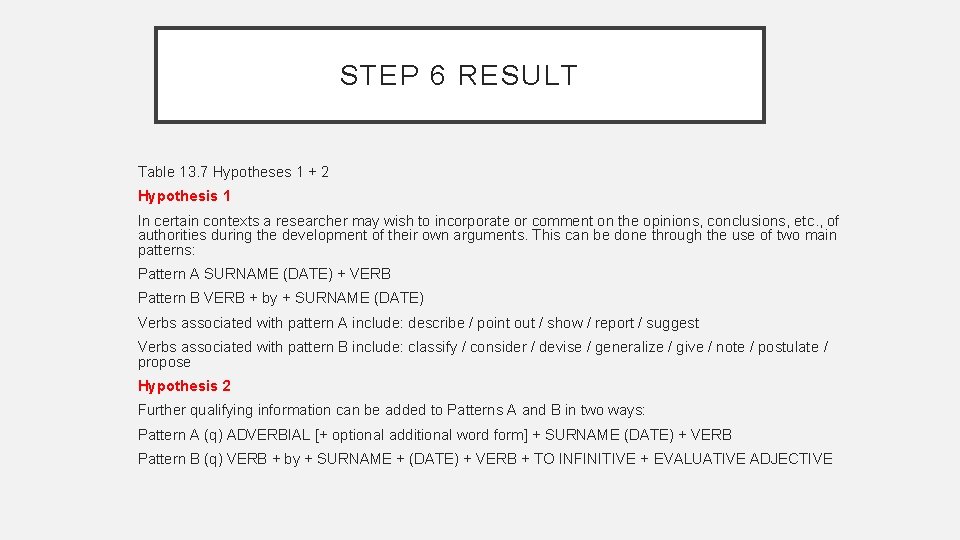

STEP 6 RESULT Table 13. 7 Hypotheses 1 + 2 Hypothesis 1 In certain contexts a researcher may wish to incorporate or comment on the opinions, conclusions, etc. , of authorities during the development of their own arguments. This can be done through the use of two main patterns: Pattern A SURNAME (DATE) + VERB Pattern B VERB + by + SURNAME (DATE) Verbs associated with pattern A include: describe / point out / show / report / suggest Verbs associated with pattern B include: classify / consider / devise / generalize / give / note / postulate / propose Hypothesis 2 Further qualifying information can be added to Patterns A and B in two ways: Pattern A (q) ADVERBIAL [+ optional additional word form] + SURNAME (DATE) + VERB Pattern B (q) VERB + by + SURNAME + (DATE) + VERB + TO INFINITIVE + EVALUATIVE ADJECTIVE

STEP 7 REPEAT The seventh stage in this process (but not the final stage!) is to repeat the process with more data. This enables the researcher to test, and then extend, refine or revise the hypothesis in order to render it as robust and useful as possible for your particular purposes.

WHY CONCORDANCES ARE NOT ENOUGH Herein lies one of the limitations of the concordance and the reason why it has been necessary to develop new approaches to corpus investigation which make it possible to identify how lexical items collocate and how they are differentially distributed within and across texts and text collections.

EXPLORING CONCORDANCE LINES • Concordancing is a valuable analytical technique because it allows a large number of examples of an item to be brought together in one place, in their original context. It is useful both for hypothesis testing and for hypothesis generation. In the case of the latter, a hypothesis can be generated based on patterns observed in just a small number of lines, and subsequently tested out through further searches.

SEARCHING AND SORTING • A concordance program allows any item (a single word, a wild-card item or a string of words) to be searched for within a corpus, and the results of that search displayed on the screen. These results are known as concordances or concordance lines. All the occurrences of the target item (or node word) are displayed, vertically centred, on the screen along with a preset number of characters either side.

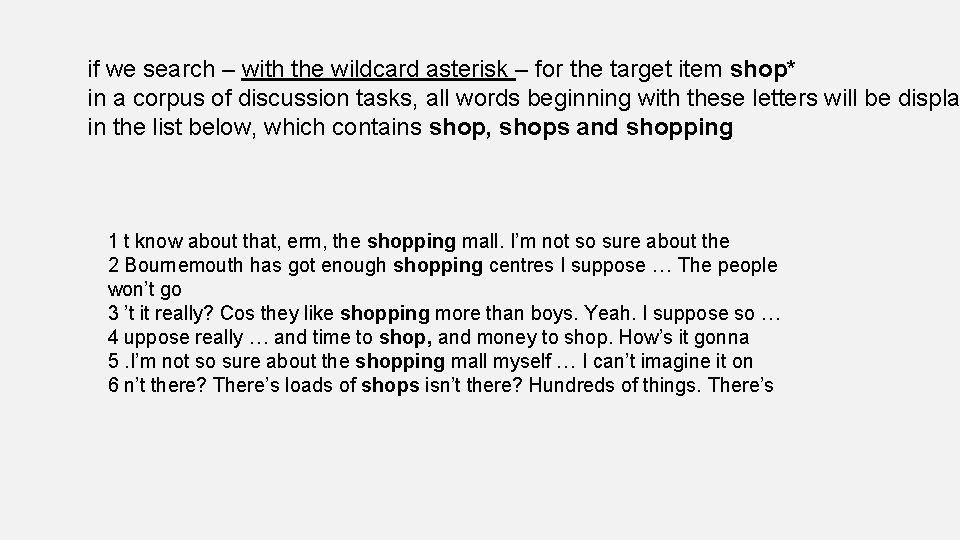

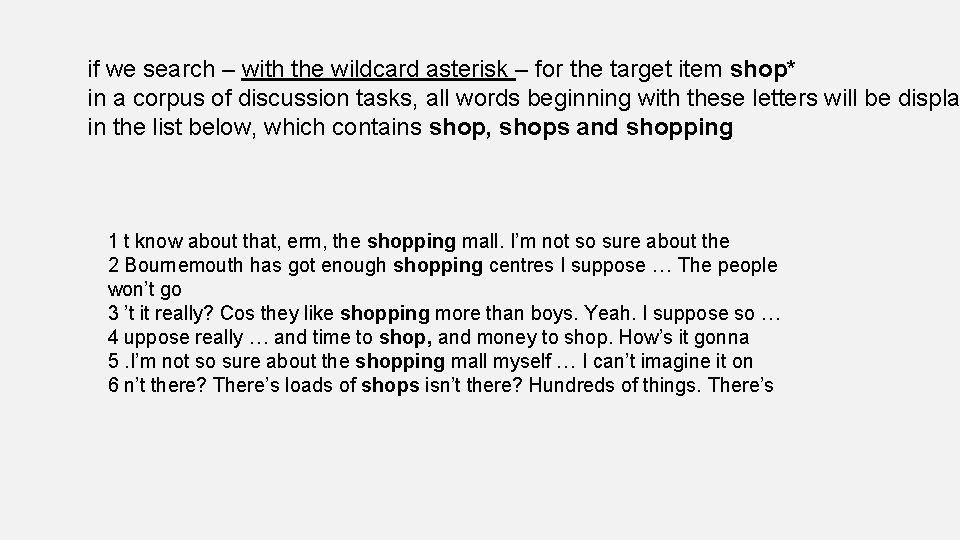

if we search – with the wildcard asterisk – for the target item shop* in a corpus of discussion tasks, all words beginning with these letters will be displa in the list below, which contains shop, shops and shopping 1 t know about that, erm, the shopping mall. I’m not so sure about the 2 Bournemouth has got enough shopping centres I suppose … The people won’t go 3 ’t it really? Cos they like shopping more than boys. Yeah. I suppose so … 4 uppose really … and time to shop, and money to shop. How’s it gonna 5. I’m not so sure about the shopping mall myself … I can’t imagine it on 6 n’t there? There’s loads of shops isn’t there? Hundreds of things. There’s

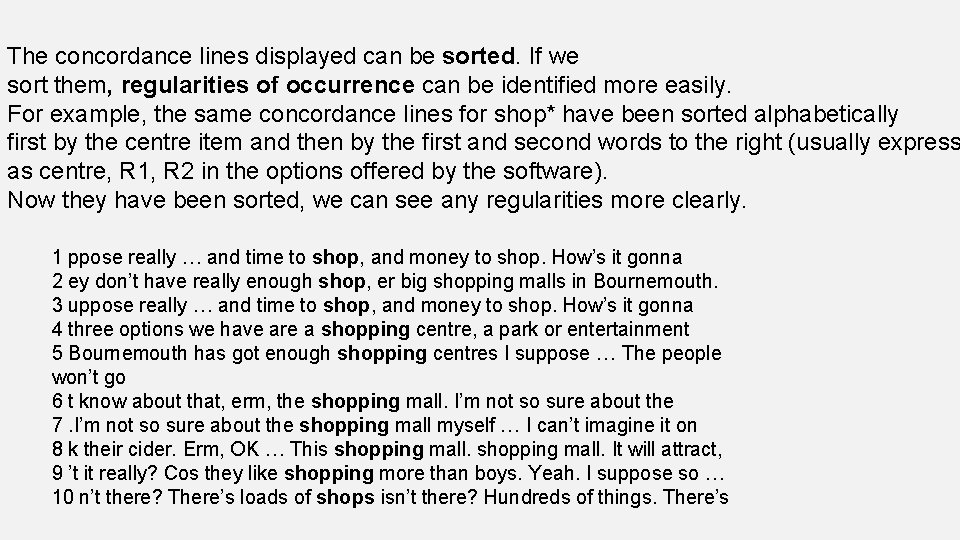

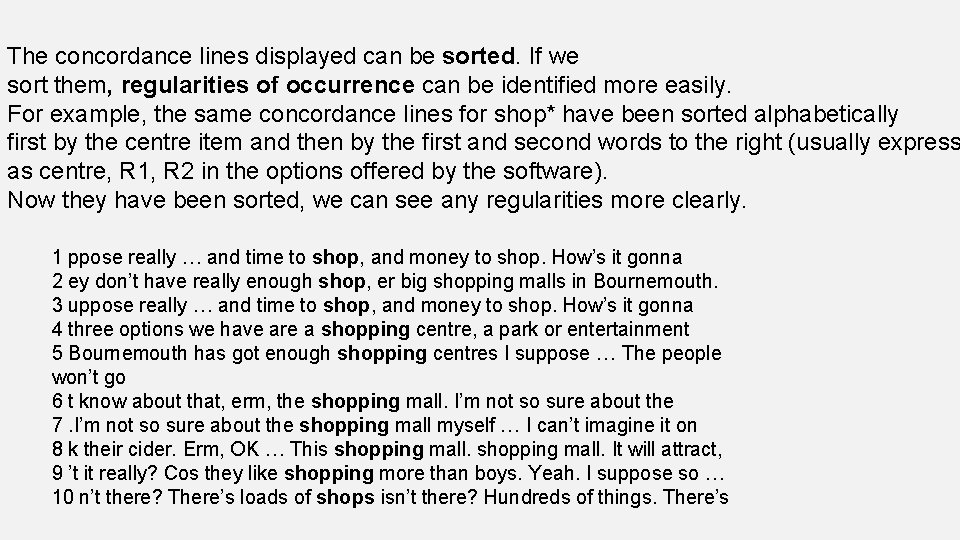

The concordance lines displayed can be sorted. If we sort them, regularities of occurrence can be identified more easily. For example, the same concordance lines for shop* have been sorted alphabetically first by the centre item and then by the first and second words to the right (usually express as centre, R 1, R 2 in the options offered by the software). Now they have been sorted, we can see any regularities more clearly. 1 ppose really … and time to shop, and money to shop. How’s it gonna 2 ey don’t have really enough shop, er big shopping malls in Bournemouth. 3 uppose really … and time to shop, and money to shop. How’s it gonna 4 three options we have are a shopping centre, a park or entertainment 5 Bournemouth has got enough shopping centres I suppose … The people won’t go 6 t know about that, erm, the shopping mall. I’m not so sure about the 7. I’m not so sure about the shopping mall myself … I can’t imagine it on 8 k their cider. Erm, OK … This shopping mall. It will attract, 9 ’t it really? Cos they like shopping more than boys. Yeah. I suppose so … 10 n’t there? There’s loads of shops isn’t there? Hundreds of things. There’s

SEARCHING AND SORTING • These very simple concordance lines demonstrate the versatility of concordance programs, and show the potential that they have to provide insight into the typicality of item use. In particular, concordance analysis can provide evidence of the most frequent meanings, or the most frequent collocates (co-occurring items) such as shopping centre or shopping mall (see Biber et al. 1998; Scott 1999; Tognini Bonelli 2001; Hunston 2002; Reppen and Simpson 2002; Mc. Enery et al. 2006).

What are concordances

What are concordances Insidan region jh

Insidan region jh Rankings: what are they and do they matter?

Rankings: what are they and do they matter? How would you describe the costumes and props they used

How would you describe the costumes and props they used Milady face shapes

Milady face shapes If we meet him tomorrow we will say hello

If we meet him tomorrow we will say hello We seek him here we seek him there

We seek him here we seek him there You are not rejected

You are not rejected Jordan 14

Jordan 14 Grammar rules frustrate me they're not logical they are so

Grammar rules frustrate me they're not logical they are so For they not know what they do

For they not know what they do Knowledge not shared is wasted

Knowledge not shared is wasted Once upon a time okara

Once upon a time okara When should hand antiseptics be used?

When should hand antiseptics be used? Laugh with their hearts meaning

Laugh with their hearts meaning Hands search my empty pockets

Hands search my empty pockets How are they used?

How are they used? In a premix burner used in fes the fuel used is

In a premix burner used in fes the fuel used is In a premix burner used in fes the fuel used is

In a premix burner used in fes the fuel used is Poetic devices onomatopoeia

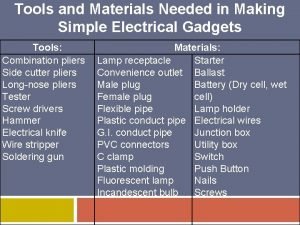

Poetic devices onomatopoeia Electrical tools with pictures and uses

Electrical tools with pictures and uses Write the character sketch of margie

Write the character sketch of margie