Valuation of the Firms Cash Flows CHAPTER 9

- Slides: 31

Valuation of the Firm’s Cash Flows —CHAPTER 9—

Cash flows and investment decisions An assessment of anticipated cash flows lies at the heart of the firm’s investment decision making. Nevertheless, a great deal of uncertainty must inevitably surround any estimation of future cash flows. As the economist John Maynard Keynes put it: “Our knowledge of the factors that will govern the yield of an investment in some years hence is usually very slight and often negligible”.

“Uncertainty” versus “Risk” In Chapter 5, the estimated cash flow was represented as an expected outcome. In effect, we were assuming that the future is uncertain in the sense that we have some range of outcome possibilities together with their attached probabilities. We were, in effect envisioning the future as that of throwing a dice: we do not know the outcome, but we do know the range of possibilities and the probability to be attached to each. Such a state is technically referred to a one of risk. Thus, we were in fact substituting a state of “risk” for what in reality is more likely to be a case of “genuine uncertainty”.

A framework for discounting cash flows Nevertheless, if we are to make a start at some kind of meaningful assessment of the future cash flows from a project, it becomes almost necessary that we seek to identify the future with a finite range of possible cash flows, to each of which we are able to attach some notion of probability (the equivalent of throwing a dice). Notwithstanding that such a model fails to adequately capture the genuine uncertainty facing an investment, the exercise can be useful in serving to highlight the key variables relating to the investment that are likely to determine the financial success or failure of the undertaking. The exercise is dangerous, however, when we allow ourselves to be seduced by the model to the point of losing a critical recognition of the model’s limitations.

Discounting can lead to heated debate! The discounting of future cash flows is particularly important in situations when a firm’s valuation is a basis for negotiation between two parties; for example, in cases of contested mergers and acquisitions. In these negotiations, both sides will seek to argue as to how the cash flows should be discounted as it suits their purpose to either talk up or talk down the outcome valuations. The discounting of future cash flows is also applied to the regulation of utility industries (electricity, water, etc. ), where the discounted valuation of cash flows determines the price at which the utility must be priced to the public. Again, arguments as to “correct discounting” can be fiercely contested. The discounting of future cash flows is also required in the privatization of state enterprises, when such calculations are applied to determine the fair offer price to the public.

Methods of discounting: the CFE (k. E) approach It is possible to identify the firm’s projected cash flow to shareholders as projected dividends to shareholders. Alternatively, we may focus on the free cash flow to equity (CFE) that the project (firm) makes available to shareholders.

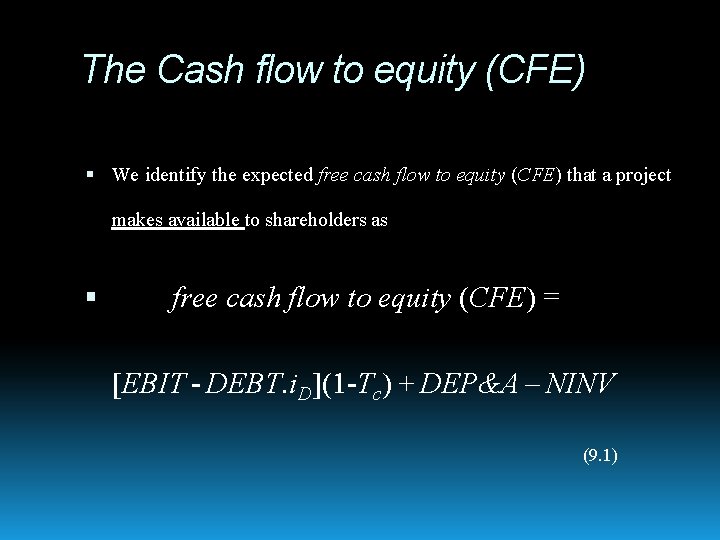

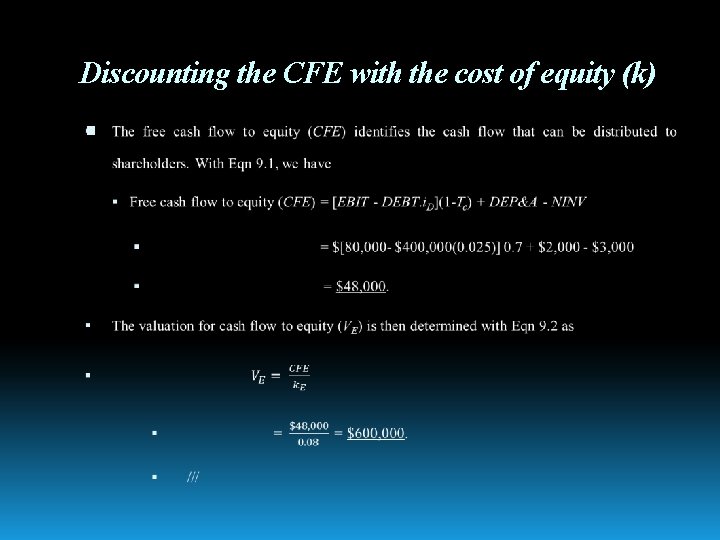

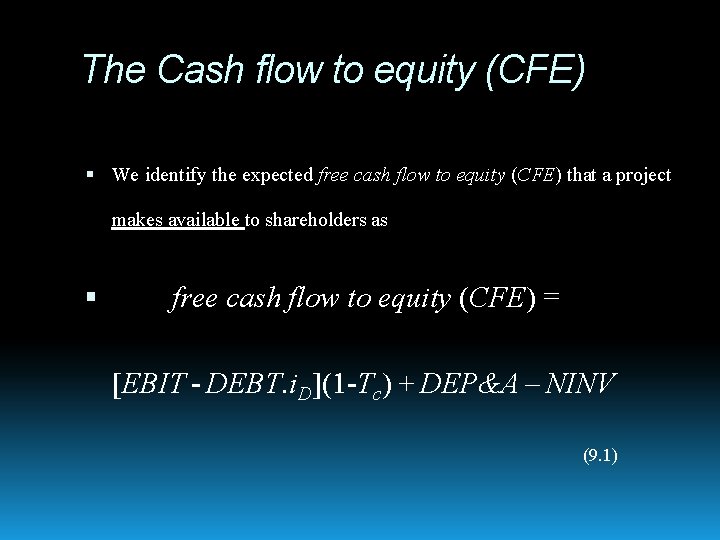

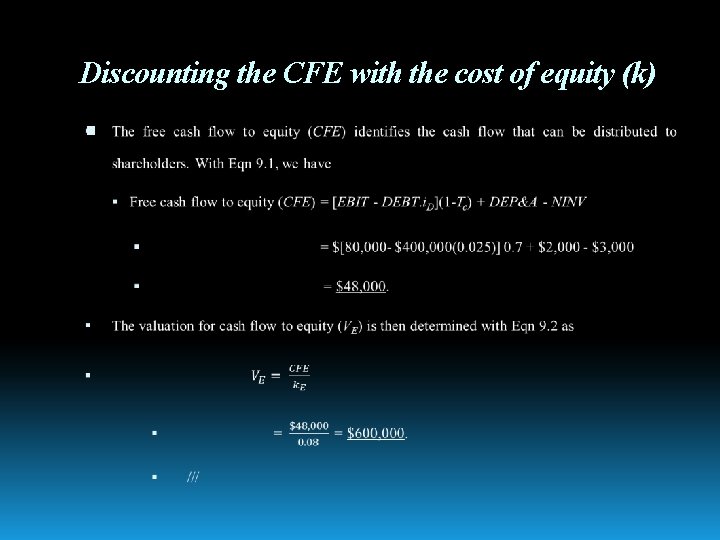

The Cash flow to equity (CFE) We identify the expected free cash flow to equity (CFE) that a project makes available to shareholders as free cash flow to equity (CFE) = [EBIT - DEBT. i. D](1 -Tc) + DEP&A – NINV (9. 1)

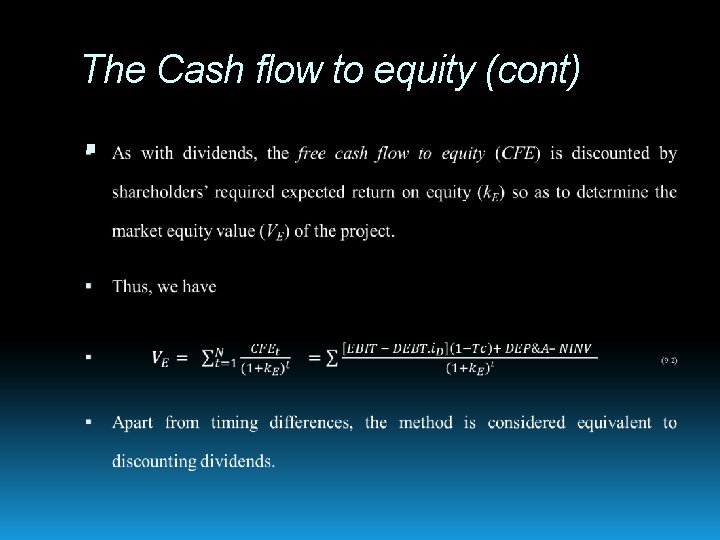

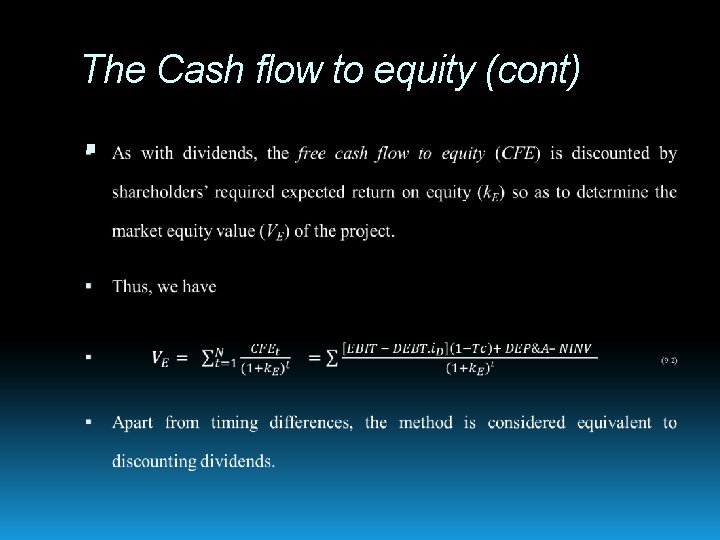

The Cash flow to equity (cont)

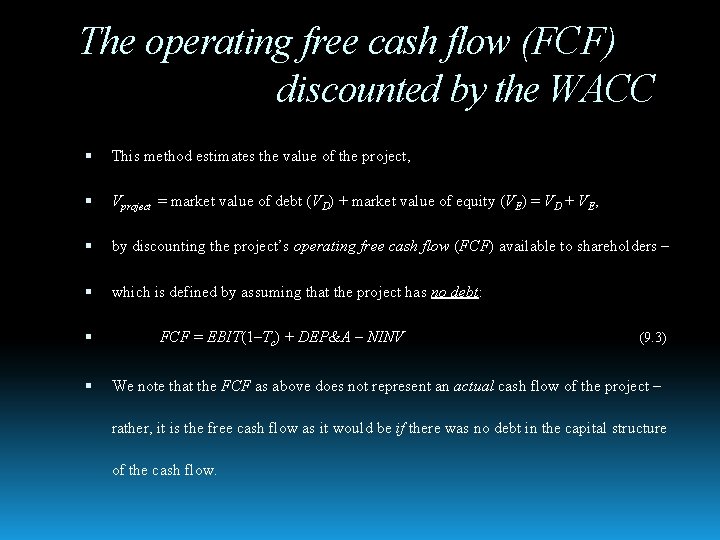

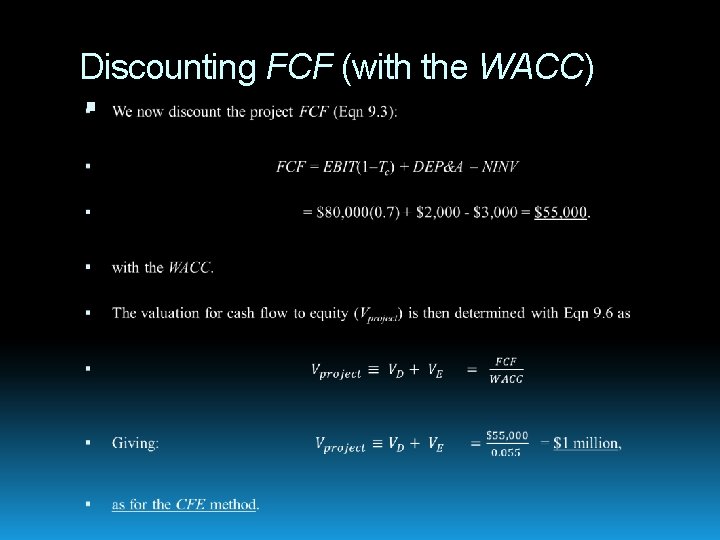

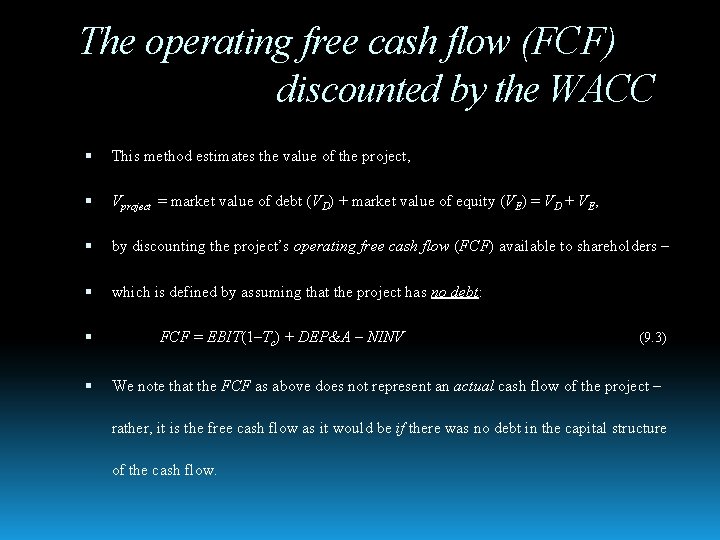

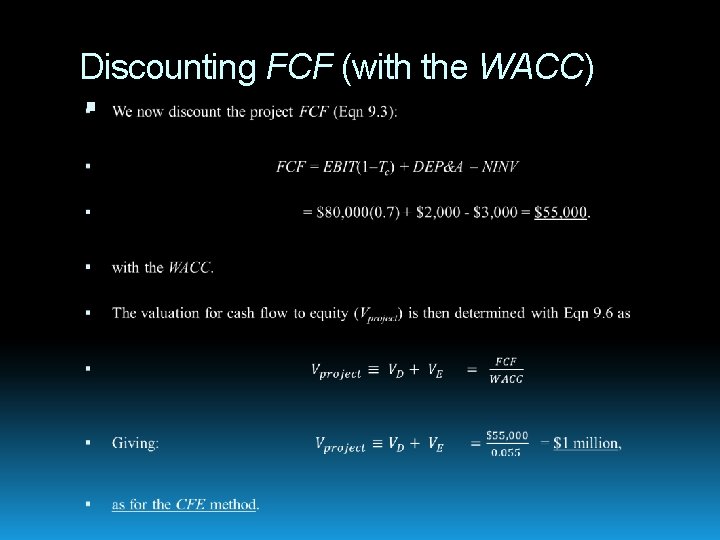

The operating free cash flow (FCF) discounted by the WACC This method estimates the value of the project, Vproject = market value of debt (VD) + market value of equity (VE) = VD + VE, by discounting the project’s operating free cash flow (FCF) available to shareholders – which is defined by assuming that the project has no debt: FCF = EBIT(1–Tc) + DEP&A – NINV (9. 3) We note that the FCF as above does not represent an actual cash flow of the project – rather, it is the free cash flow as it would be if there was no debt in the capital structure of the cash flow.

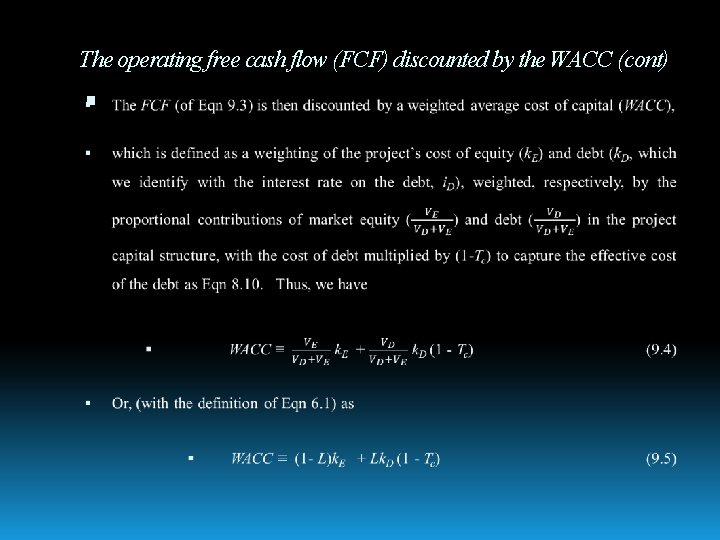

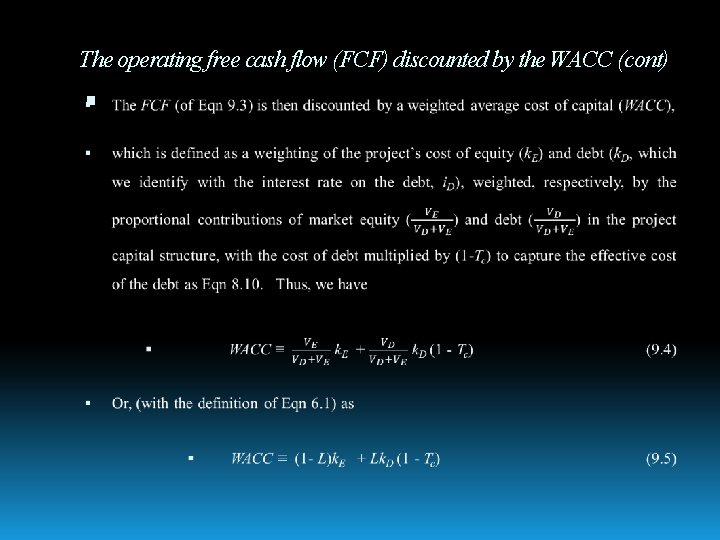

The operating free cash flow (FCF) discounted by the WACC (cont)

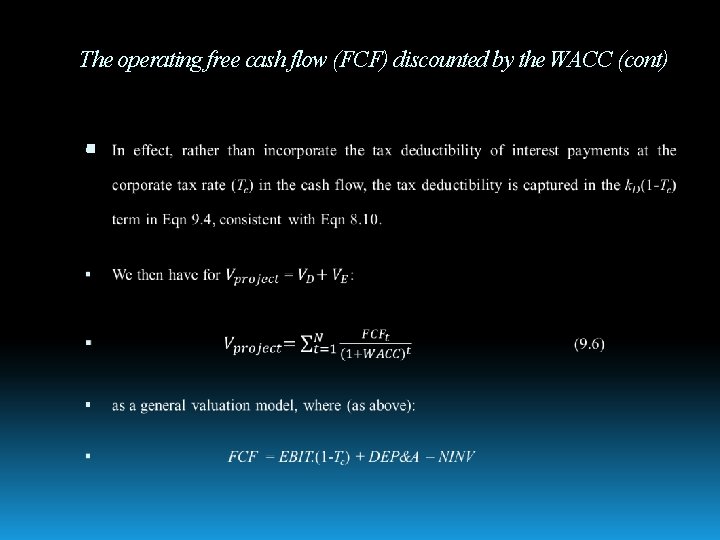

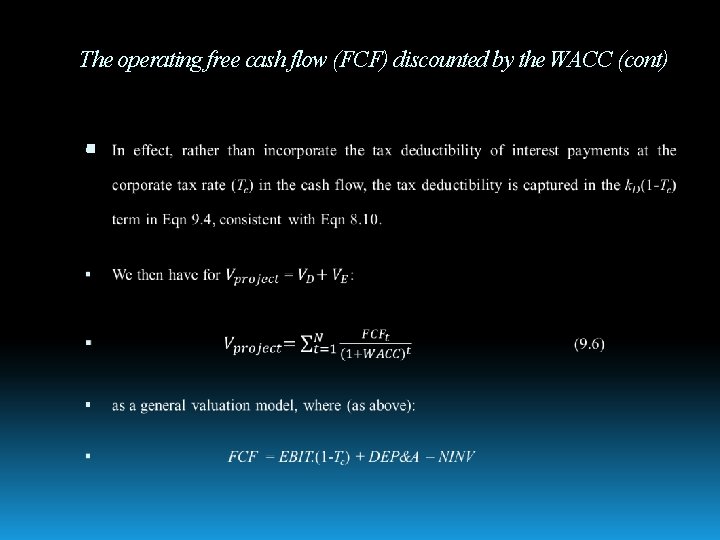

The operating free cash flow (FCF) discounted by the WACC (cont)

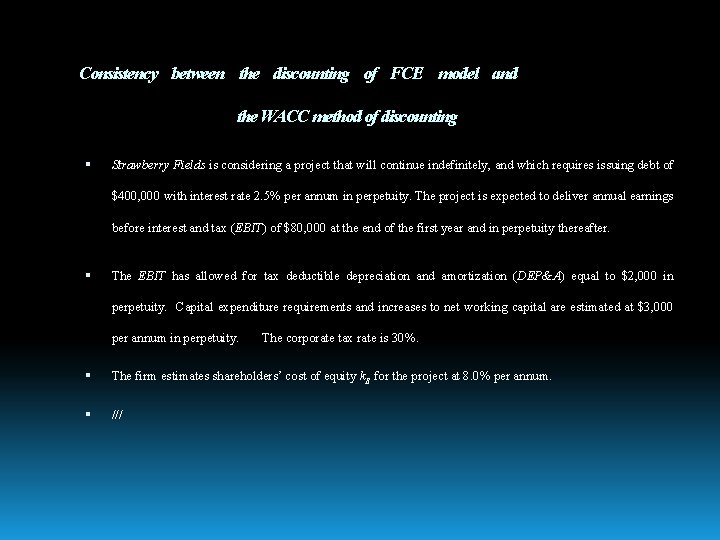

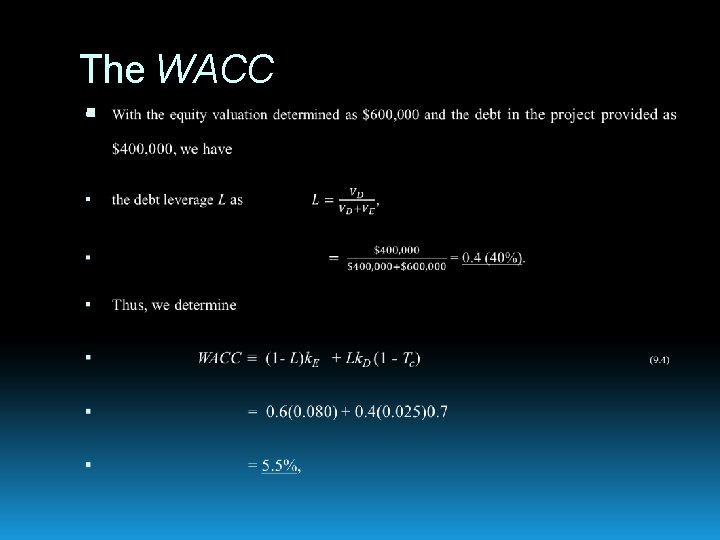

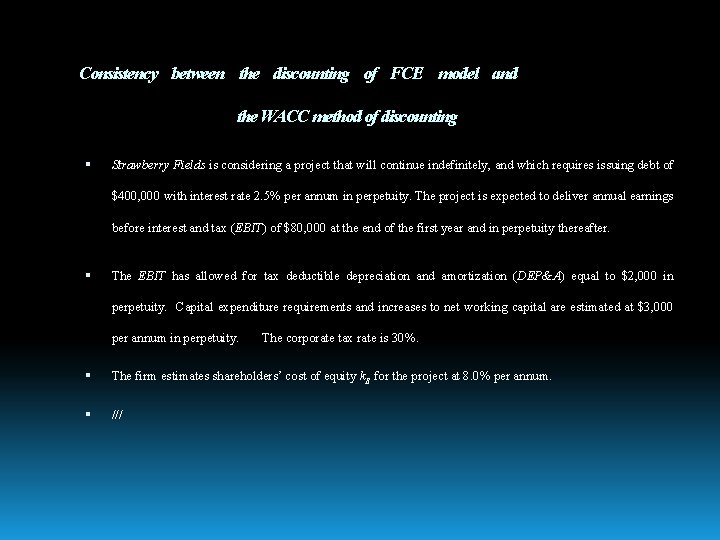

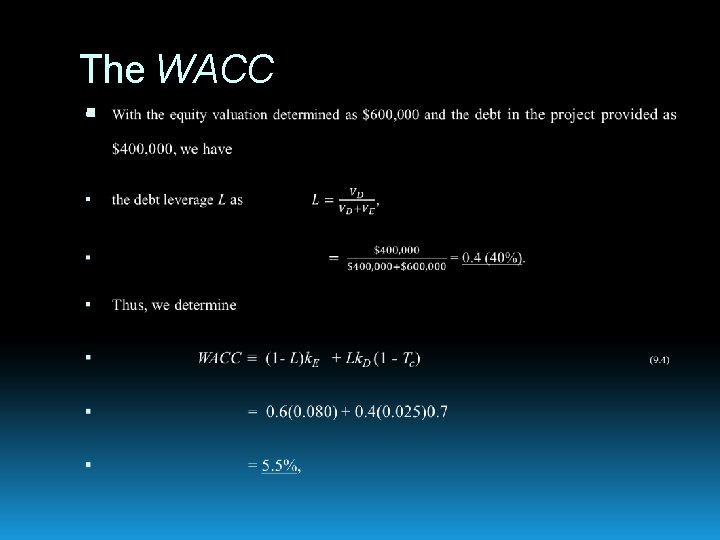

Consistency between the discounting of FCE model and the WACC method of discounting Strawberry Fields is considering a project that will continue indefinitely, and which requires issuing debt of $400, 000 with interest rate 2. 5% per annum in perpetuity. The project is expected to deliver annual earnings before interest and tax (EBIT) of $80, 000 at the end of the first year and in perpetuity thereafter. The EBIT has allowed for tax deductible depreciation and amortization (DEP&A) equal to $2, 000 in perpetuity. Capital expenditure requirements and increases to net working capital are estimated at $3, 000 per annum in perpetuity. The corporate tax rate is 30%. The firm estimates shareholders’ cost of equity k. E for the project at 8. 0% per annum. ///

Discounting the CFE with the cost of equity (k)

The WACC

Discounting FCF (with the WACC)

Break time

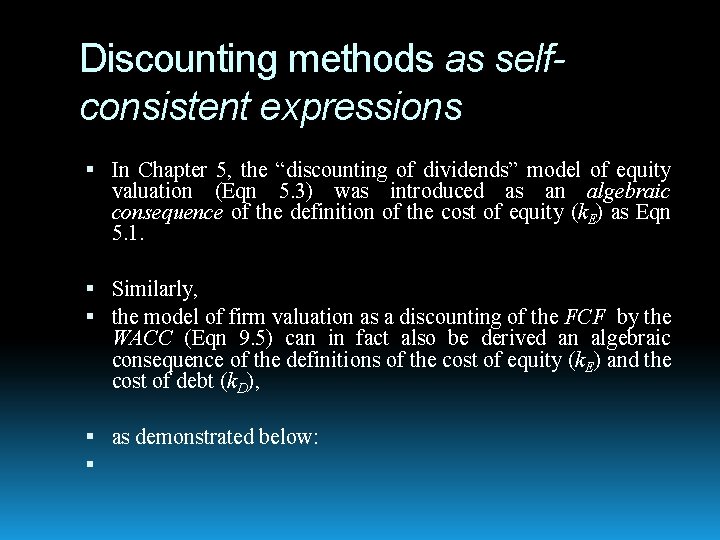

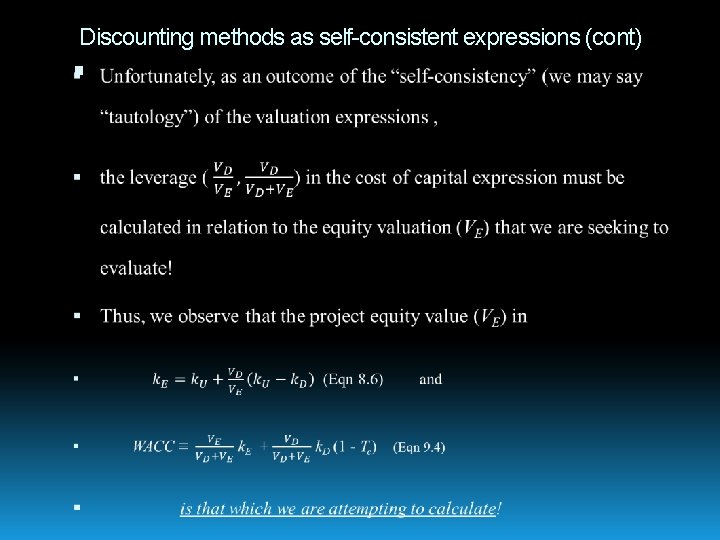

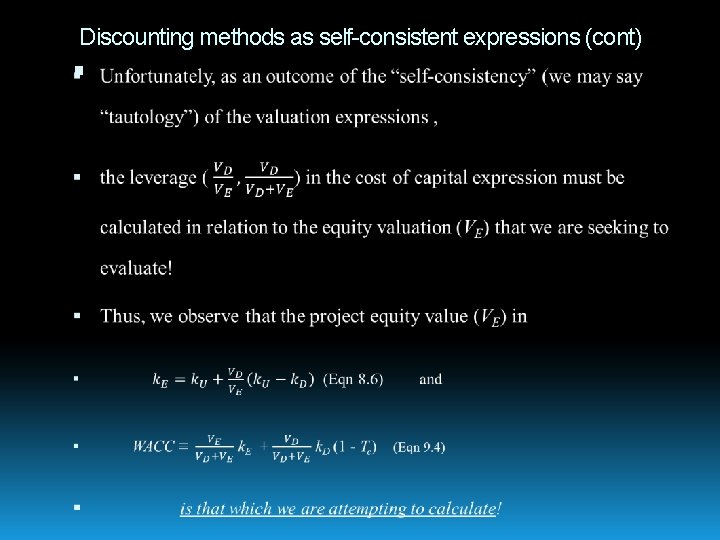

Discounting methods as selfconsistent expressions In Chapter 5, the “discounting of dividends” model of equity valuation (Eqn 5. 3) was introduced as an algebraic consequence of the definition of the cost of equity (k. E) as Eqn 5. 1. Similarly, the model of firm valuation as a discounting of the FCF by the WACC (Eqn 9. 5) can in fact also be derived an algebraic consequence of the definitions of the cost of equity (k. E) and the cost of debt (k. D), as demonstrated below:

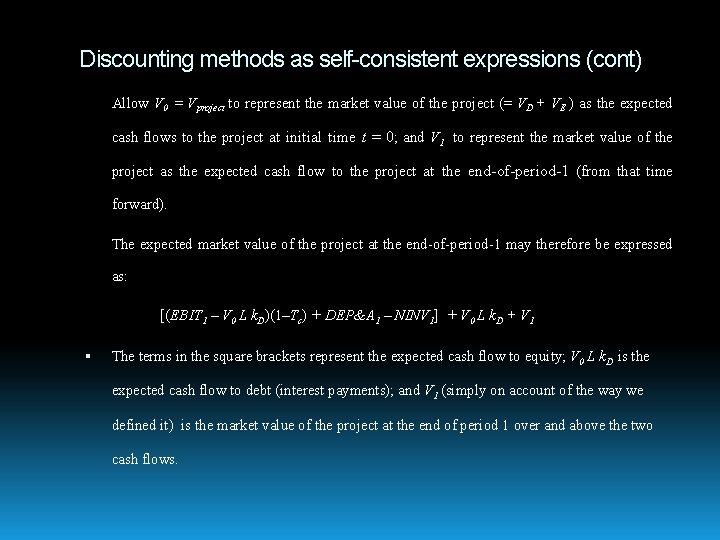

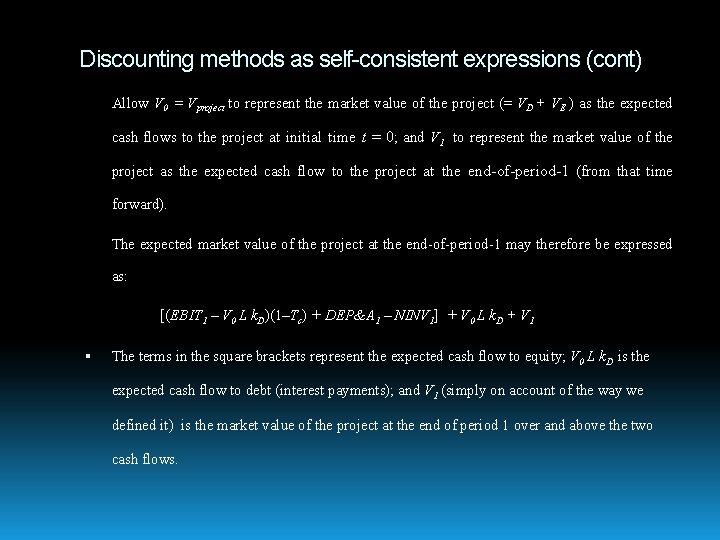

Discounting methods as self-consistent expressions (cont) Allow V 0 = Vproject to represent the market value of the project (= VD + VE ) as the expected cash flows to the project at initial time t = 0; and V 1 to represent the market value of the project as the expected cash flow to the project at the end-of-period-1 (from that time forward). The expected market value of the project at the end-of-period-1 may therefore be expressed as: [(EBIT 1 – V 0 L k. D)(1–Tc) + DEP&A 1 – NINV 1] + V 0 L k. D + V 1 The terms in the square brackets represent the expected cash flow to equity; V 0 L k. D is the expected cash flow to debt (interest payments); and V 1 (simply on account of the way we defined it) is the market value of the project at the end of period 1 over and above the two cash flows.

Discounting methods as self-consistent expressions (cont)

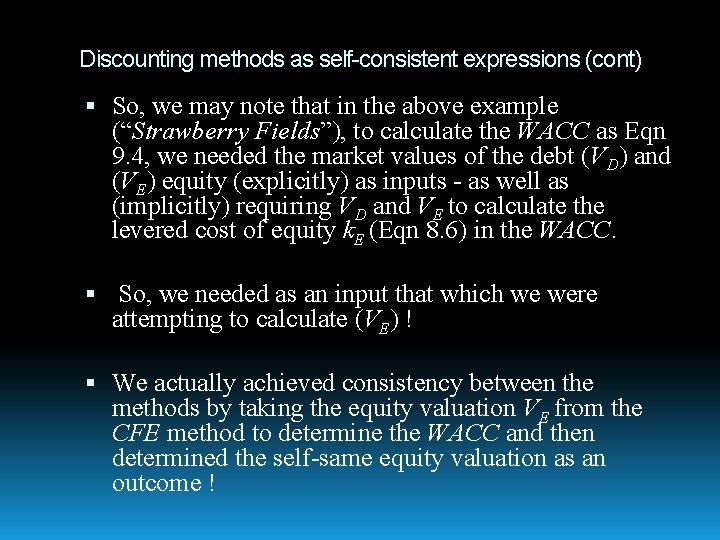

Discounting methods as self-consistent expressions (cont) So, we may note that in the above example (“Strawberry Fields”), to calculate the WACC as Eqn 9. 4, we needed the market values of the debt (VD) and (VE) equity (explicitly) as inputs - as well as (implicitly) requiring VD and VE to calculate the levered cost of equity k. E (Eqn 8. 6) in the WACC. So, we needed as an input that which we were attempting to calculate (VE) ! We actually achieved consistency between the methods by taking the equity valuation VE from the CFE method to determine the WACC and then determined the self-same equity valuation as an outcome !

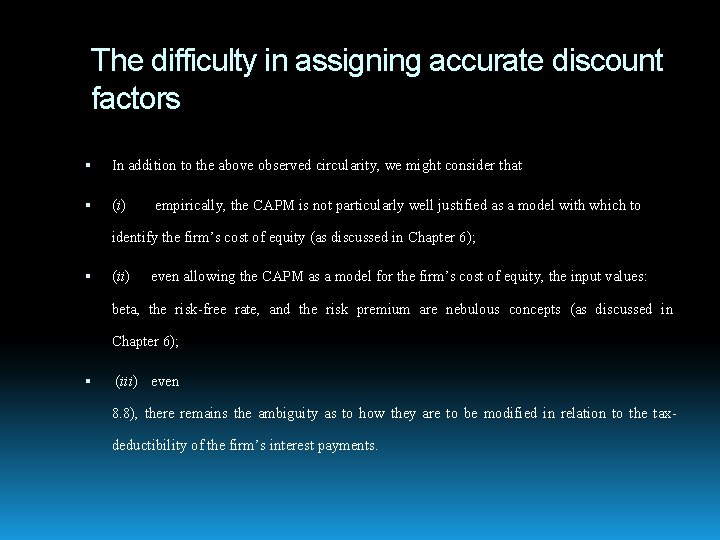

The difficulty in assigning accurate discount factors In addition to the above observed circularity, we might consider that (i) empirically, the CAPM is not particularly well justified as a model with which to identify the firm’s cost of equity (as discussed in Chapter 6); (ii) even allowing the CAPM as a model for the firm’s cost of equity, the input values: beta, the risk-free rate, and the risk premium are nebulous concepts (as discussed in Chapter 6); (iii) even 8. 8), there remains the ambiguity as to how they are to be modified in relation to the taxdeductibility of the firm’s interest payments.

The Reality In other words, Not only do we generally not have a great deal of confidence in (1) the project cash flows to be discounted, but, we do not generally have a great deal of confidence in (2) the appropriate discount rate to be applied.

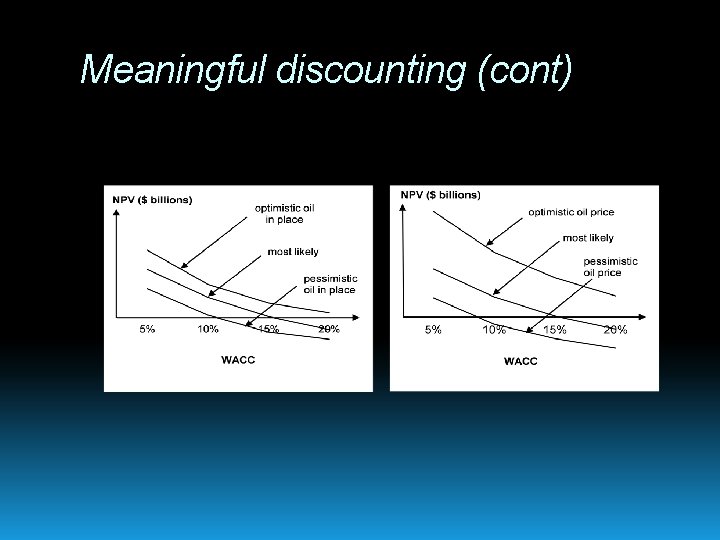

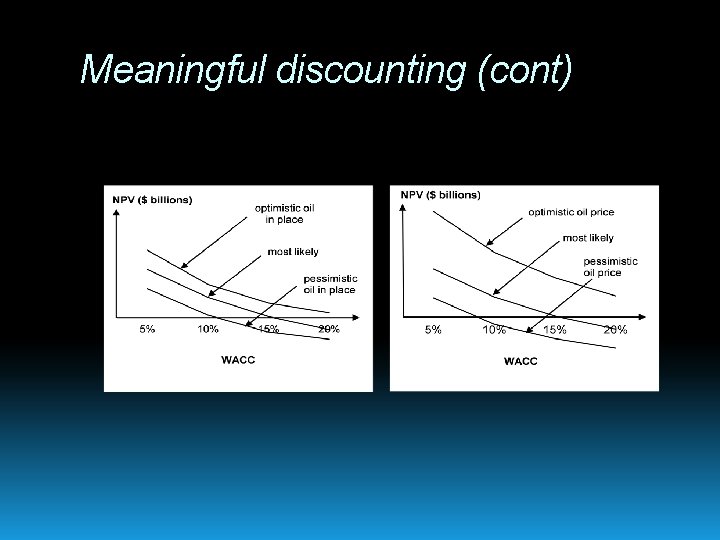

Meaningful discounting However, meaningful cash flow valuations are possible provided the valuations are made to highlight the sensitivity of the cash flow to key variables across a range of discount rates. To see what might be involved, consider an assessment for the development of a petroleum reserve. The key input variables that are likely to “make or break” such a project are generally identified as (i) the size of the reserves, and (ii) the future price of oil. Thus, the company geologists will typically be asked to provide an “optimistic”, “most probable” and a “pessimistic” estimate of the petroleum reserves, while the economists are charged with estimating “optimistic”, “most probable” and “pessimistic” estimates of future oil prices.

Meaningful discounting (cont) Suppose that the company uses a WACC of, say, 10%. With such value it can calculate a NPV with the most likely estimates of the inputs in the calculations. However, rather than “run with a single NPV” value, the calculations will typically be presented as a function of the discount factor for each variation of the key input variables (size of the reserve, future price of oil) as depicted over.

Meaningful discounting (cont)

Meaningful discounting (cont) Intelligently presented, NPV calculations assist the decision- maker to highlight the financial viability of the project. Nevertheless, we might bear in mind the reality that both (i) the projected cash flows, and (ii) the discount factor to be applied to cash flows, are both highly uncertain entities.

Meaningful discounting (cont) Not perhaps surprisingly, there is more to important investment decision-making than the calculation of a single NPV ! The behavioral dimensions of people making decisions in organizations against an uncertain future imply that decision-making is ultimately socially constructed in the context of the firm.

Meaningful discounting (cont) Chapter 12 seeks to convey how investment decision-making in large firms is a more complex phenomenon than the mechanistic calculation of net present values (NPVs). “Reputations based on past performance” and “commitment and trust relationships” contribute to the ultimate decision to either accept or reject a project.

Review The “discounting of dividends” (alternatively, cash flow to equity) model, and the WACC model are algebraically equivalent. The WACC model is much preferred on account of being less sensitive to leverage (debt in the project). Nevertheless, the WACC model is strictly “circular” in requiring as input the valuation that is the objective of the exercise. However, meaningful cash flow valuations are possible provided the valuations are made to highlight the sensitivity of the cash flow to key variables across a range of discount rates.

Raw materials budget example

Raw materials budget example Prepaid expense in cash flow statement

Prepaid expense in cash flow statement Capital budgeting

Capital budgeting Chapter 13 statement of cash flows

Chapter 13 statement of cash flows Chapter 23 statement of cash flows

Chapter 23 statement of cash flows Chapter 13 statement of cash flows

Chapter 13 statement of cash flows Flow chapter 13

Flow chapter 13 Cash received from customers

Cash received from customers Intermediate accounting chapter 23

Intermediate accounting chapter 23 Chapter 6 discounted cash flow valuation

Chapter 6 discounted cash flow valuation Fixed income valuation

Fixed income valuation At the most fundamental level firms generate cash and

At the most fundamental level firms generate cash and Pv of cash flows formula

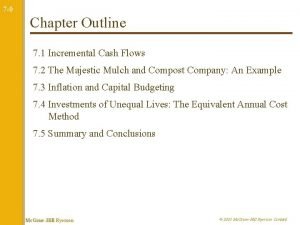

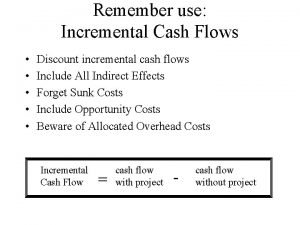

Pv of cash flows formula Incremental cash flows

Incremental cash flows Payback time formula

Payback time formula Cash flow indirect method

Cash flow indirect method Incremental cash flows

Incremental cash flows Incremental cash flow

Incremental cash flow Incremental cash flows definition

Incremental cash flows definition Examples of incremental cash flows

Examples of incremental cash flows Partial statement of cash flows

Partial statement of cash flows Operating investing and financing activities

Operating investing and financing activities Pro forma statement of cash flows

Pro forma statement of cash flows The statement of cash flows reports

The statement of cash flows reports 2/10 net 30

2/10 net 30 Relevant cash flows definition

Relevant cash flows definition The statement of cash flows classifies items as

The statement of cash flows classifies items as The statement of cash flows helps users

The statement of cash flows helps users Cash flow estimation

Cash flow estimation Statement of cash flows partial

Statement of cash flows partial What is incremental cash flow

What is incremental cash flow Managing operating exposure

Managing operating exposure