Shakespeares Style Prose and Poetry Prose Words or

![Sonnet from Romeo and Juliet: ROMEO [To JULIET] If I profane with my unworthiest Sonnet from Romeo and Juliet: ROMEO [To JULIET] If I profane with my unworthiest](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/810bf075e69f7ad0dbfd4d8cc4c234cc/image-11.jpg)

- Slides: 17

Shakespeare’s Style: Prose and Poetry

Prose Words or ideas are arranged in no fixed pattern of strong or weak beats Often used for “common” speech, by lower class characters Example: Sir Toby says, “What a plague means my niece to take the death of her brother thus? I am sure care’s an enemy to life” (1. 3. 1 -2).

Background: Poetry Up until the late 1500 s, all English plays were written in verse (poetry). Hence, playwrights in Shakespeare’s day were called poets. Audiences in Shakespeare’s day expected to hear the actors speak in verse. Shakespeare’s plays were meant to be heard (they weren’t published in his day, and most of the population was illiterate anyway) This rhythm made it easier to follow

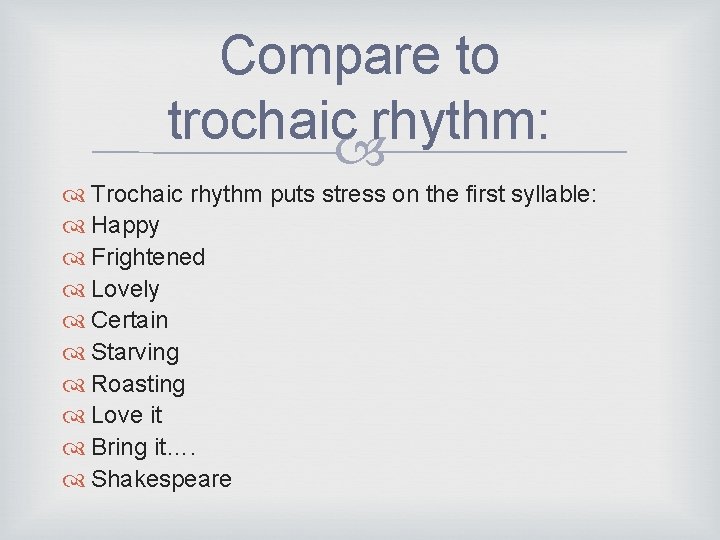

How the rhythm works: Iambic Place your right hand over your heart You’ll feel the familiar thump: DA-DUM, DA-DUM This rhythm is called “iambic” in other words, the weak beat is first and the strong beat is second: DA-DUM, DA-DUM

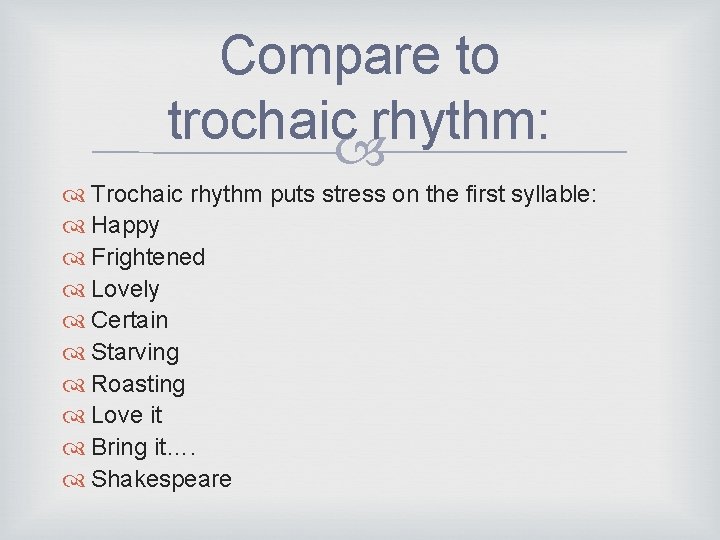

Some words with iambic rhythm: Although Because Unless Today Perhaps For sure I think Indeed delight

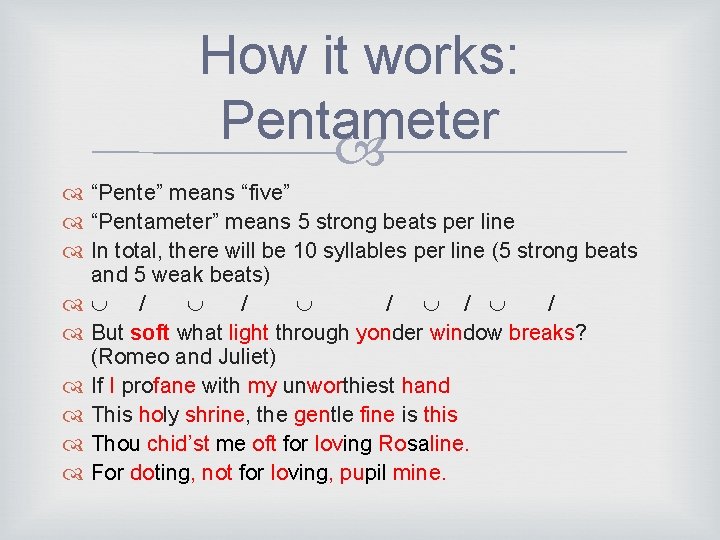

Compare to trochaic rhythm: Trochaic rhythm puts stress on the first syllable: Happy Frightened Lovely Certain Starving Roasting Love it Bring it…. Shakespeare

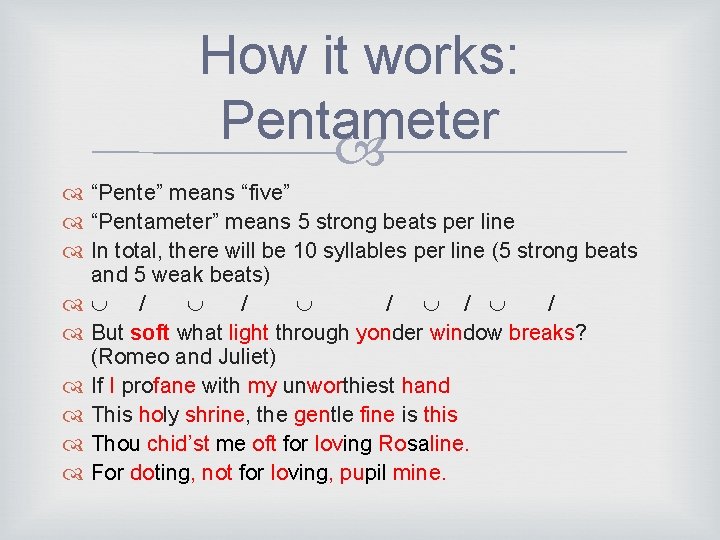

How it works: Pentameter “Pente” means “five” “Pentameter” means 5 strong beats per line In total, there will be 10 syllables per line (5 strong beats and 5 weak beats) / / / But soft what light through yonder window breaks? (Romeo and Juliet) If I profane with my unworthiest hand This holy shrine, the gentle fine is this Thou chid’st me oft for loving Rosaline. For doting, not for loving, pupil mine.

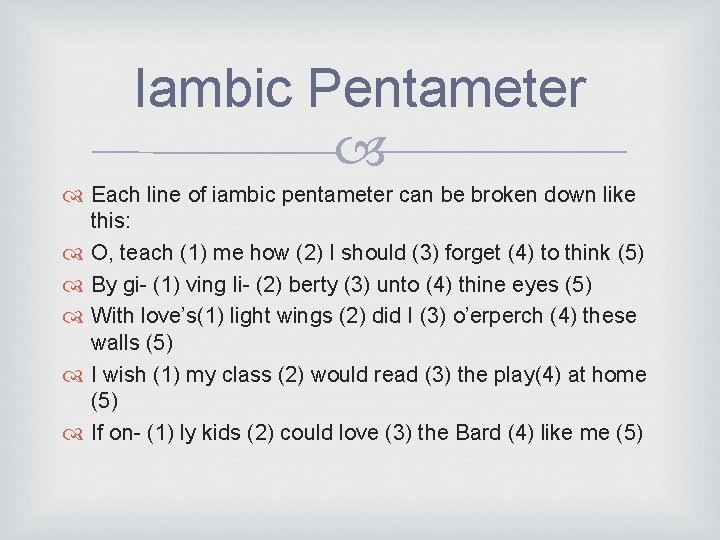

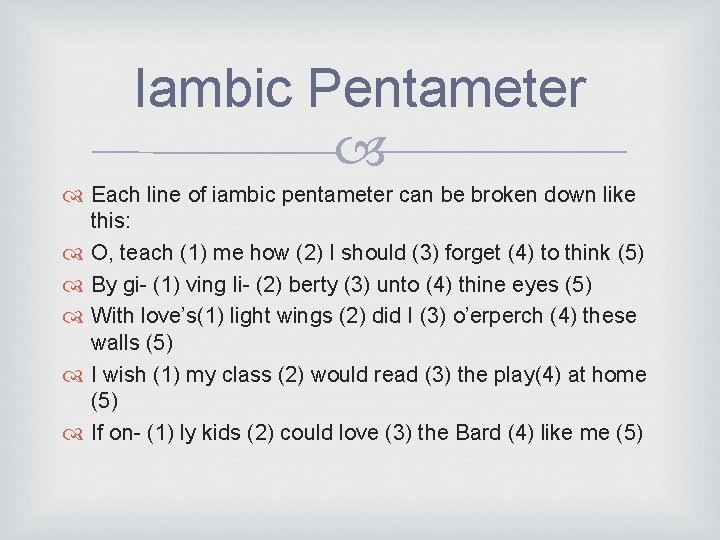

Iambic Pentameter Each line of iambic pentameter can be broken down like this: O, teach (1) me how (2) I should (3) forget (4) to think (5) By gi- (1) ving li- (2) berty (3) unto (4) thine eyes (5) With love’s(1) light wings (2) did I (3) o’erperch (4) these walls (5) I wish (1) my class (2) would read (3) the play(4) at home (5) If on- (1) ly kids (2) could love (3) the Bard (4) like me (5)

Blank verse… Iambic pentameter that does not rhyme is called blank verse Example: Rebellious subjects, enemies of peace, Profaners of this neighbour-stained steel, Will they not hear? —What, ho! You men, you beasts, That quench the fire of your pernicious rage With purple fountains issuing from your veins,

Sonnet A 14 line poem Rhyme scheme: abab cdcd efef gg Shakespeare wrote 154 sonnets Sometimes characters’ lines combine to make a sonnet

![Sonnet from Romeo and Juliet ROMEO To JULIET If I profane with my unworthiest Sonnet from Romeo and Juliet: ROMEO [To JULIET] If I profane with my unworthiest](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/810bf075e69f7ad0dbfd4d8cc4c234cc/image-11.jpg)

Sonnet from Romeo and Juliet: ROMEO [To JULIET] If I profane with my unworthiest hand This holy shrine, the gentle fine is this: My lips, two blushing pilgrims, ready stand To smooth that rough touch with a tender kiss. JULIET Good pilgrim, you do wrong your hand too much, Which mannerly devotion shows in this; For saints have hands that pilgrims' hands do touch, And palm to palm is holy palmers' kiss. ROMEO Have not saints lips, and holy palmers too? JULIET Ay, pilgrim, lips that they must use in prayer. ROMEO O, then, dear saint, let lips do what hands do; They pray, grant thou, lest faith turn to despair. JULIET Saints do not move, though grant for prayers' sake. ROMEO Then move not, while my prayer's effect I take.

Soliloquy Speech spoken by one person, seemingly to himself/herself but really to inform the audience of his motives and to reveal true character. Often is it a kind of internal debate. Example: (2. 2. 38 -42) “Tis but thy name that is my enemy; Thou art thyself, though not a Montague. What’s Montague? It is nor hand, nor foot, Nor arm, nor face, nor any other part Belonging to a man. O, be some other name!

Oxymoron A figure of speech in which two or more contrasting ideas are placed beside each other, often in parallel grammatical form. The purpose is to emphasize the ideas being contrasted Examples: Romeo: O brawling love! O loving hate! (1. 1. 172) Juliet: Parting is such sweet sorrow. (2. 2. 184)

Aside Actor’s comment or a short speech meant to be heard by the audience and not by other performers Example: on the balcony, while Juliet is speaking to herself… Romeo: [Aside. ] Shall I hear more, or shall I speak at this? (2. 2. 37)

Rhyming couplet Two rhyming lines are called a rhyming couplet A rhyming couplet will usually complete a long speech or a scene Example: Hence will I to my ghostly father’s cell, His help to crave, and my dear hap to tell. (2. 2. 188 -9)

Allusion A reference to a historical, literary, religious, mythological figure, event or object (the reader makes the association) Example: “She’ll not be hit with Cupid’s arrow She hat Dian’s wit. (1. 1. 205 -6) At lovers’ perjuries, / They say, Jove laughs. (2. 2. 934)

Sources: Gibson, Rex, and Field-Pickering, Janet. Discovering Shakespeare’s Language. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1998. Print. “Stressing Shakespeare. ” Literary Cavalcade 54. 7 (2002): 10. Literary Reference Center Plus. Web. 16 May 2013.

Shakespeare tragedy about racism and jealousy

Shakespeare tragedy about racism and jealousy Shakespeare tragedy about racism and jealousy

Shakespeare tragedy about racism and jealousy Romeo's father

Romeo's father Shakespeare career

Shakespeare career Hamlet themes

Hamlet themes Idioms shakespeare

Idioms shakespeare Uil prose and poetry

Uil prose and poetry Drama acrostic poem

Drama acrostic poem Quiz on elizabethan drama

Quiz on elizabethan drama Elizabethan poetry and prose

Elizabethan poetry and prose Unseen prose

Unseen prose Hebrew poetry characteristics

Hebrew poetry characteristics Elizabethan poetry and prose

Elizabethan poetry and prose Types of unseen prose

Types of unseen prose Poetry commentary example

Poetry commentary example Unseen prose and poetry

Unseen prose and poetry Russell prose style

Russell prose style Scientific prose style examples

Scientific prose style examples