Understanding the Language Language Poetry and Prose Shakespeares

- Slides: 11

Understanding the Language

Language -- Poetry and Prose Shakespeare’s plays are written in a combination of prose and poetry. � Prose ◦ Written or spoken language in its ordinary form, without metrical structure. � Poetry ◦ A form of literature that uses aesthetic and rhythmic qualities.

Terms You Know � Personification, alliteration, assonance, onomatopoeia, rhyme, and repetition—you know these. � Imagery – using words to create a mental image � Oxymoron – two (opposite) words brought together: sweet sorrow, heavy lightness, feather of lead. � Verse – succession of metrical feet written, printed, or orally composed as one line; one of the lines of a poem.

Terms You Should Also Know �Stanza – a poetic paragraph �Monologue – a long speech by one actor to other characters on stage. �Soliloquy – a long speech by an actor speaking his/her thoughts aloud. �Aside – a brief remark by the characters revealing his thoughts or feelings to the audience, unheard by the other actors.

Terms You Ought to Know (because they’re fun) � Puns – using a word(s) with more than one meaning for a comic effect: “Ask for me tomorrow, and you shall find me a grave man. ” grave = serious, or a place to be buried. ◦ I’ve been to the dentist several times so I know the drill. ◦ I wondered why the baseball was getting bigger, then it hit me. ◦ I’m glad I know sign language; it’s pretty handy. ◦ To write with a broken pencil is pointless.

Poetic Terms Meter or Foot –a unit of rhythm, the pattern of beats. � Meters with two-syllable feet: ◦ IAMS of IAMBIC – a short followed by a long or unstressed followed by a stressed (x /) : That time of year thou mayst in me behold ta-DUM, ta-DUM) ◦ TROCHEES or TROCHAIC –long followed by short, or stressed followed by unstressed (/ x): ◦ Tell me not in mournful numbers TA-dum, TA-dum ◦ SPONDEES or SPONDAIC – two equally accented syllables (/ /): Cry, cry! Troy burns, or élse let Hélen gó. � Meters with three-syllable feet: ◦ ANAPESTIC (x x /): And the sound of a voice that is still ta-ta-DUM, ta-ta-DUM ◦ DACTYLIC (/ x x): This is the forest primeval, the murmuring pines and the hemlock (a trochee replaces the final dactyl) TA-dum, TA-dum

Poetic Terms Continued Each line of poetry contains a certain number of feet. � Trimeter [tri-meh-ter] – verse of three feet. � Tetrameter [te-tram-i-ter] – a verse of four feet. � Pentameter [pen-tam-i-ter] – a line of verse consisting of five metrical feet. � Hexameter – [hex–am-i-ter] a line of verse containing six metrical feet.

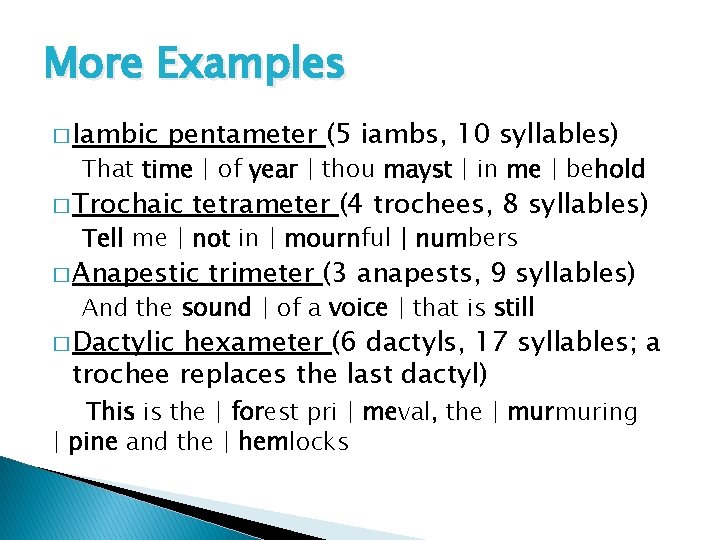

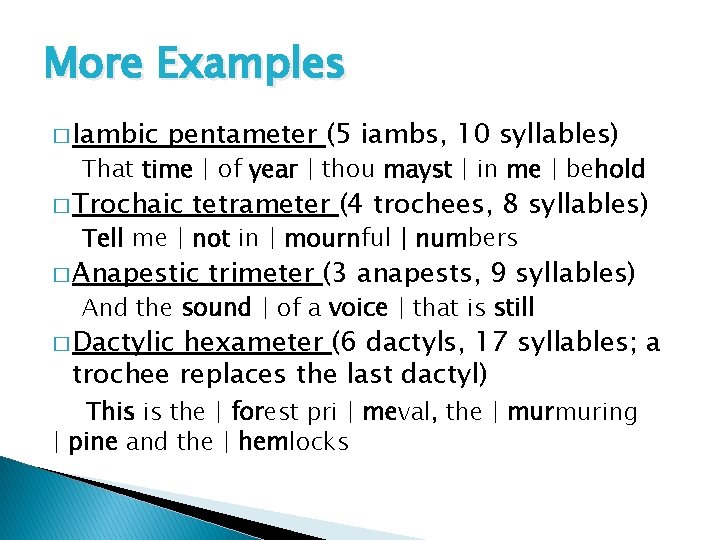

More Examples � Iambic pentameter (5 iambs, 10 syllables) That time | of year | thou mayst | in me | behold � Trochaic tetrameter (4 trochees, 8 syllables) Tell me | not in | mournful | numbers � Anapestic trimeter (3 anapests, 9 syllables) And the sound | of a voice | that is still � Dactylic hexameter (6 dactyls, 17 syllables; a trochee replaces the last dactyl) This is the | forest pri | meval, the | murmuring | pine and the | hemlocks

Language -- Pronouns � ‘Thou’ can imply either closeness or contempt, friendship towards an equal, or superiority over a social inferior. � ‘You’ is a more formal and distant form of address suggesting respect for a superior or courtesy to a social equal. � Note: Shakespeare never stuck rigidly to any of the aforementioned rules.

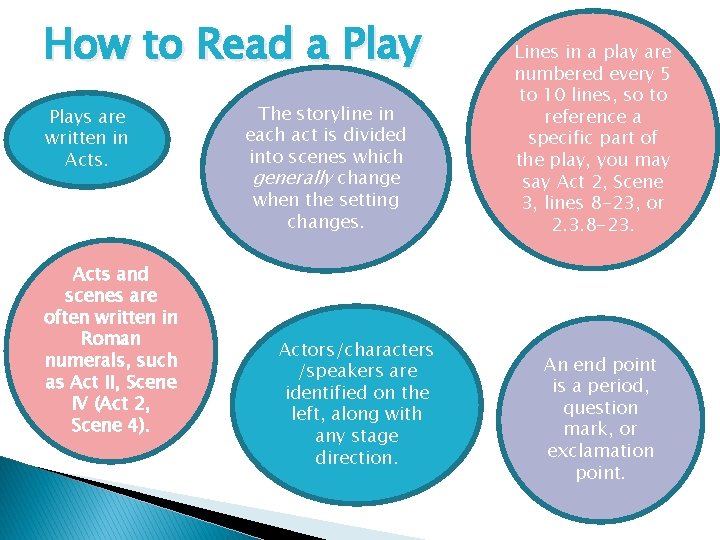

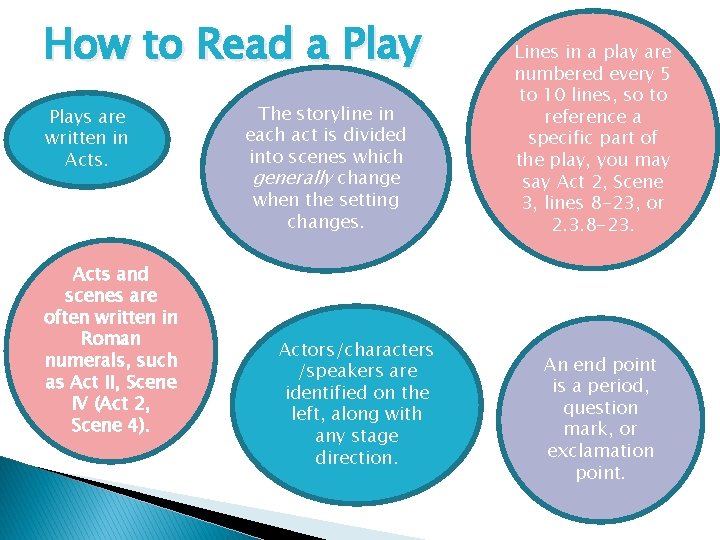

How to Read a Plays are written in Acts and scenes are often written in Roman numerals, such as Act II, Scene IV (Act 2, Scene 4). The storyline in each act is divided into scenes which generally change when the setting changes. Actors/characters /speakers are identified on the left, along with any stage direction. Lines in a play are numbered every 5 to 10 lines, so to reference a specific part of the play, you may say Act 2, Scene 3, lines 8 -23, or 2. 3. 8 -23. An end point is a period, question mark, or exclamation point.

Play Types