Medicaid Can Do More to Help Smokers Quit

- Slides: 28

Medicaid Can Do More to Help Smokers Quit Leighton Ku, Ph. D, MPH Professor, Health Policy & Management October 2016

Background • Smoking: #1 preventable cause of morbidity and mortality • About 32% of Medicaid enrollees smoke. Twice the rate of the general population (17%) [2014 NHIS] • Medicaid: largest insurance program in the US, serving about 70 million. Still growing due to ACA. • About 15% of Medicaid expenditures due to smoking. About $75 billion in 2016. • 1998 Master Settlement Agreement: tobacco industry paid over $200 billion to states due to high Medicaid costs. • National health objectives to reduce smoking include expanding smoking cessation coverage in Medicaid.

Big Picture: Insurance & Prevention • US spends more than $3 trillion for health care and insurance, mostly for acute care after problems occur. • Insurance pays medical bills and define what is covered. Key concept is “medical necessity” based on a diagnosis. • Historically, prevention services sometimes not covered because there was no diagnosis of an illness. • Insurers also worry that prevention might not lower cost burden in that year. • Prevention services gradually added. ACA required coverage for effective prevention services (e. g. , vaccinations, contraception, smoking cessation).

Massachusetts Tobacco Cessation • In 2006, MA began a comprehensive Medicaid cessation benefit, coupled with an outreach plan, including quitlines. • Land et al (2010 a) found smoking prevalence fell by about from 38% to 28%. • Land et al (2010 b) found the rate of cardiovascular hospitalizations among users fell by a third to half. • # of CVD deaths due to smoking exceeds lung-related. • Richard et al (2012) found that every $1 spent on cessation benefits was associated with about $3 in lower Medicaid hospital costs. A $2 return on investment.

Medicaid Coverage Policies • As of 2014, all states cover some tobacco cessation drugs and counseling. Not just for pregnant women. Often have barriers like copayments or prior authorization. • Many physicians & patients not aware of benefits. Use of counselling appears uncommon. • CDC collects info about tobacco coverage, but little known about use of benefits. • Broad aims: to assess state Medicaid efforts in smoking cessation and why states differ, how these are associated with actual smoking behavior and how to bolster smoking cessation.

FDA Approved Cessation Medications • Most smokers want to quit and try but relapse. Repeated attempts often needed. Medications increase quit rates. Help reduce craving for tobacco to ease withdrawal. • Nicotine Replacement Therapies (NRTs): patch, gum, lozenge (available over the counter and with prescription), plus spray and inhaler. • Bupropion (Zyban) use both for smoking cessation and as antidepressant. • Varenicline (Chantix). Brand name drug. Considered more effective, but more expensive. • E-cigarettes not approved, but many use to help quit.

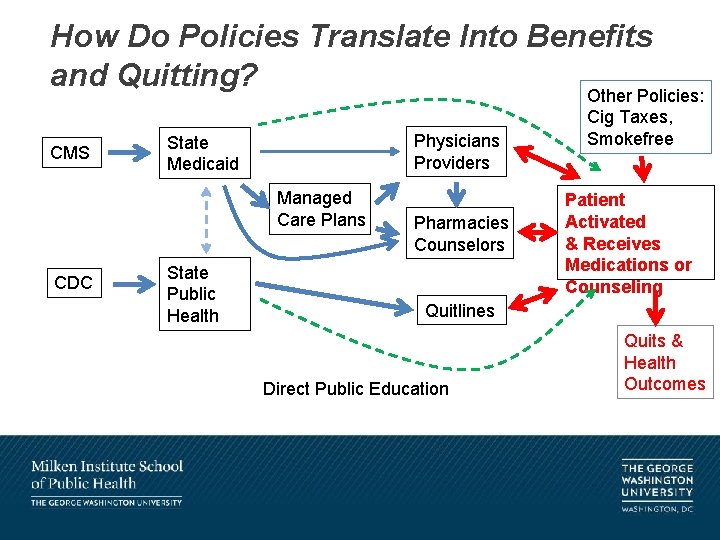

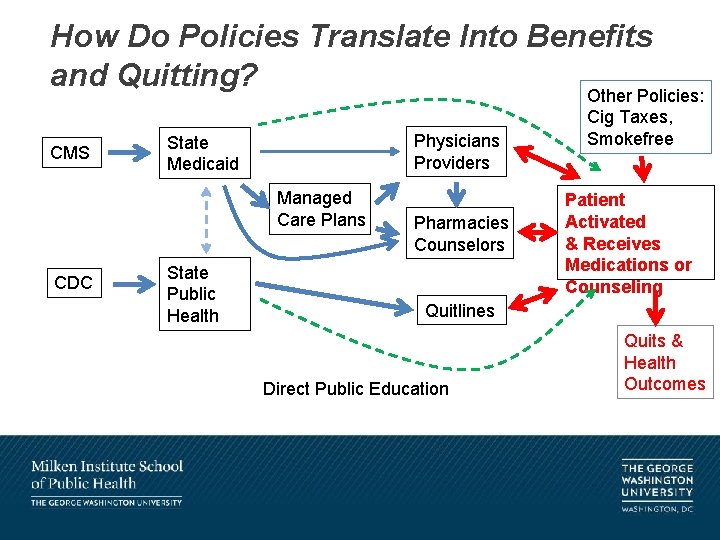

How Do Policies Translate Into Benefits and Quitting? Other Policies: CMS Physicians Providers State Medicaid Managed Care Plans CDC State Public Health Pharmacies Counselors Cig Taxes, Smokefree Patient Activated & Receives Medications or Counseling Quitlines Direct Public Education Quits & Health Outcomes

Medicaid Drug Utilization Data • Every 3 months states submit a complete list of medications Medicaid bought with specific drug data (NDC code), prescriptions, units and amounts paid. • Medicaid drug rebate system, over $16 billion/yr. • We extracted data for FDA-approved medications. • Bupropion sometimes used as anti-depressant. Hard to isolate purpose of prescription. Smoking and depression are linked. We limited data to 150 mg 12 hr dosage, which is most commonly used for cessation. • Before 2010, only FFS drugs. After 2010, also included managed care drugs.

Other Data • Drug utilization data is aggregate. No data about characteristics of users. • Medicaid claims data are available, but unwieldy and slow. Often exclude managed care data. Do not show who is smoker or not. • Drug utilization data show the numerator of use of medications, but not how many might need help. • Used annual Kaiser data about Medicaid enrollment of adults, aged and blind/disabled • Used annual BRFSS data about percent of low-income insured adults who smoke in each state

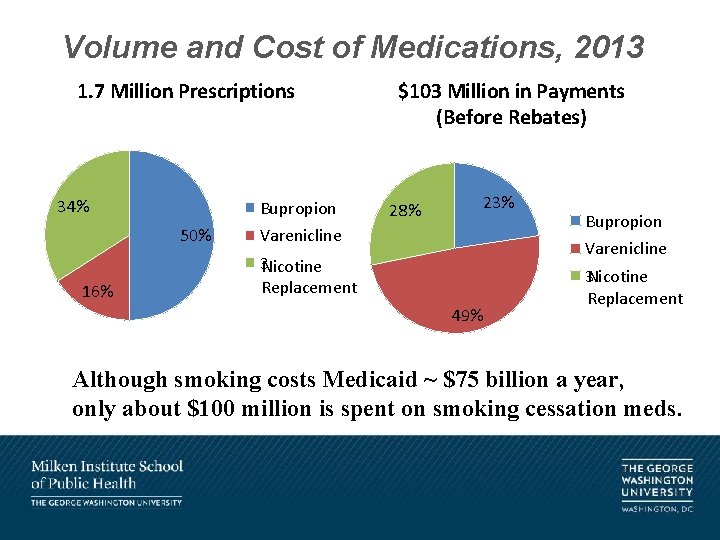

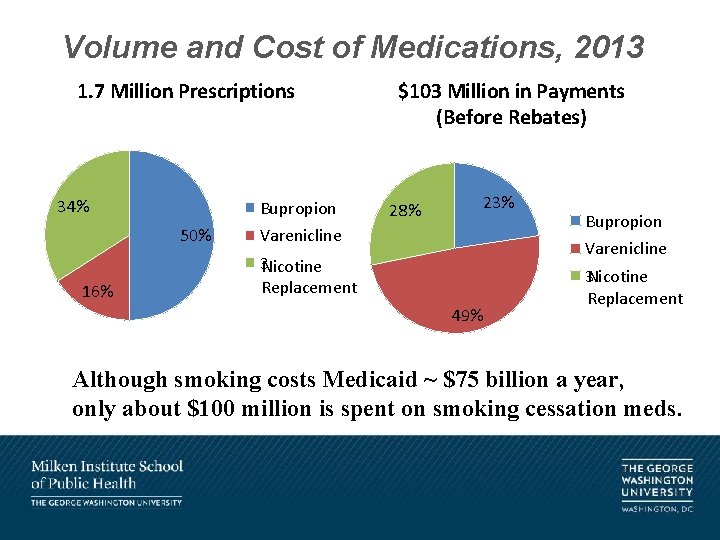

Volume and Cost of Medications, 2013 1. 7 Million Prescriptions 34% Bupropion 50% 16% $103 Million in Payments (Before Rebates) 28% 23% Varenicline Bupropion Varenicline 3 Nicotine Replacement 49% 3 Nicotine Replacement Although smoking costs Medicaid ~ $75 billion a year, only about $100 million is spent on smoking cessation meds.

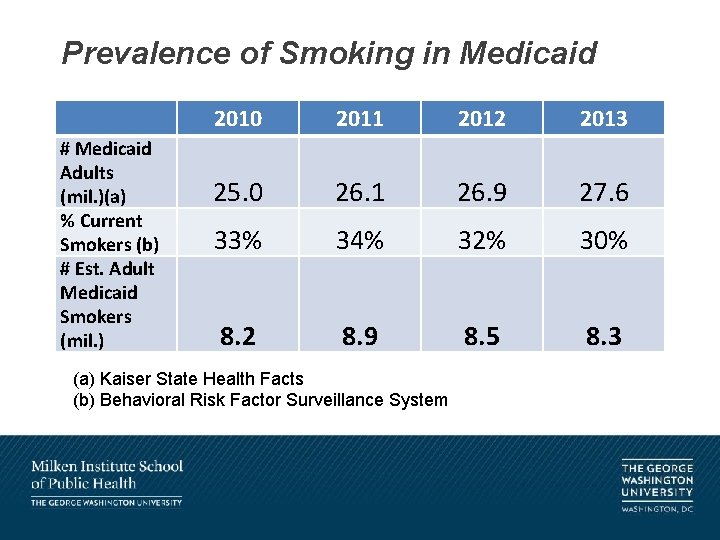

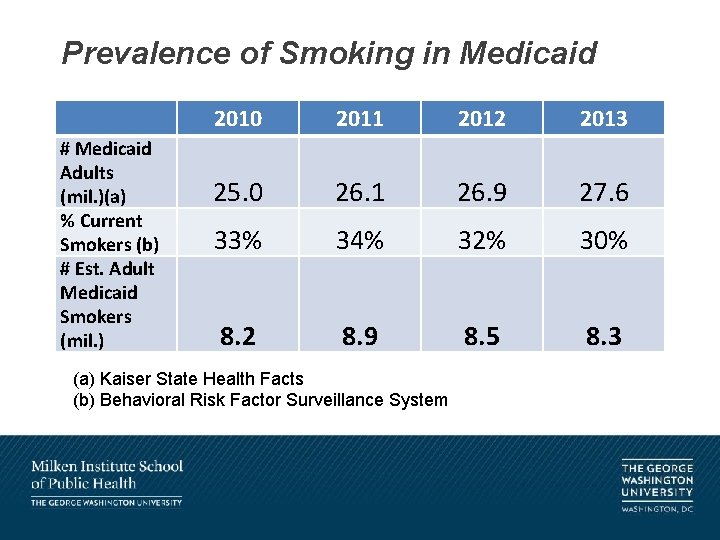

Prevalence of Smoking in Medicaid # Medicaid Adults (mil. )(a) % Current Smokers (b) # Est. Adult Medicaid Smokers (mil. ) 2010 2011 2012 2013 25. 0 26. 1 26. 9 27. 6 33% 34% 32% 30% 8. 2 8. 9 8. 5 8. 3 (a) Kaiser State Health Facts (b) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

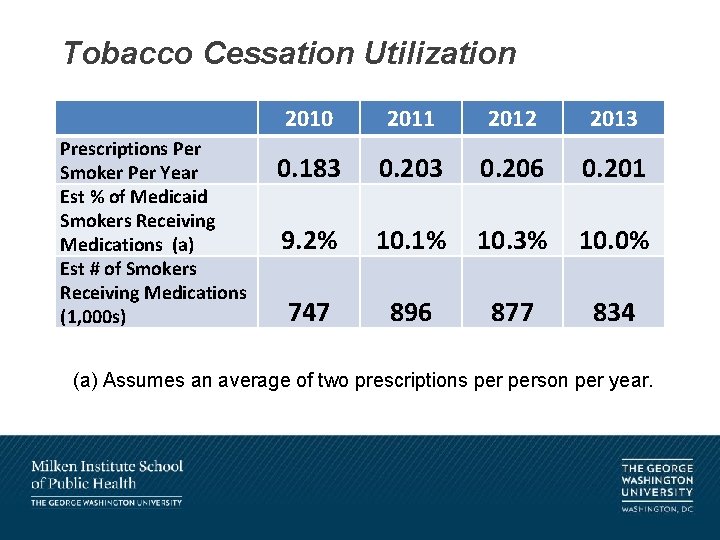

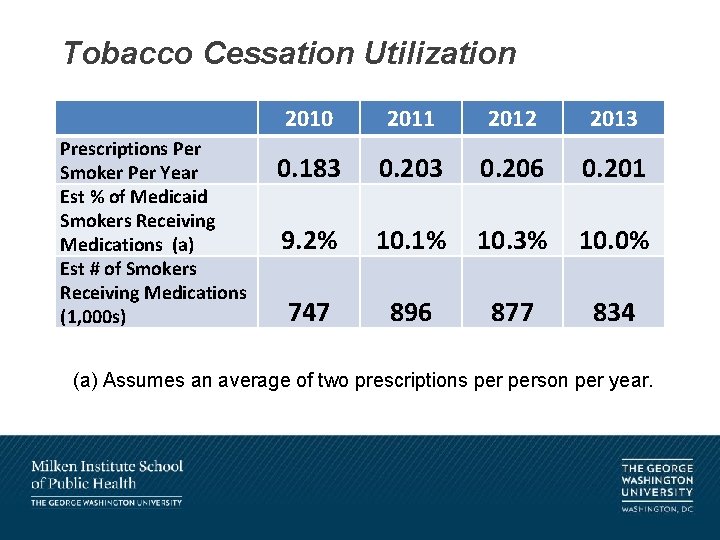

Tobacco Cessation Utilization Prescriptions Per Smoker Per Year Est % of Medicaid Smokers Receiving Medications (a) Est # of Smokers Receiving Medications (1, 000 s) 2010 2011 2012 2013 0. 183 0. 206 0. 201 9. 2% 10. 1% 10. 3% 10. 0% 747 896 877 834 (a) Assumes an average of two prescriptions person per year.

Most States Can Do More • Large differences in utilization across states: from high of. 53 prescriptions/user in MN (~27% of smokers) to. 01 in TX (<1% of smokers) • Most states could do more to promote smoking cessation in Medicaid. • There also differences in prevalence of smoking. No clear correspondence of smoking prevalence and cessation utilization. • We don’t know why these differences exist and are beginning to explore this. Having Medicaid and public health agencies give priority to this is a good start.

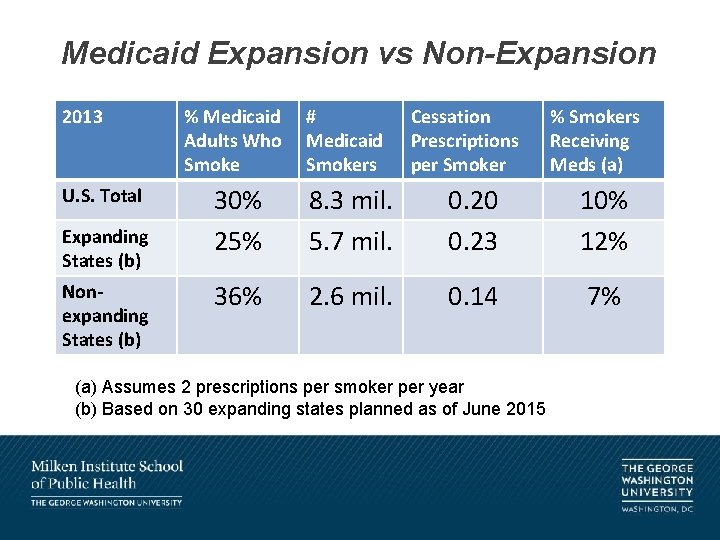

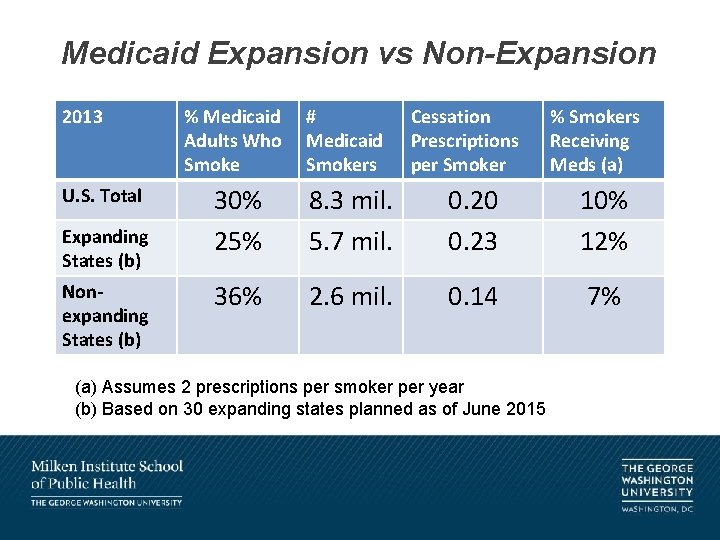

Medicaid Expansion vs Non-Expansion 2013 U. S. Total Expanding States (b) Nonexpanding States (b) % Medicaid Adults Who Smoke # Medicaid Smokers Cessation Prescriptions per Smoker % Smokers Receiving Meds (a) 30% 25% 8. 3 mil. 5. 7 mil. 0. 20 0. 23 10% 12% 36% 2. 6 mil. 0. 14 7% (a) Assumes 2 prescriptions per smoker per year (b) Based on 30 expanding states planned as of June 2015

Expansion vs Non-Expansion • We don’t believe non-expansion policies cause more smoking or less use of cessation medications. • But there are public health consequences. Non-expanding states have higher smoking prevalence, lower cessation utilization and fewer people will get access to cessation assistance through Medicaid. • Could lead to growing gap in tobacco-related health burdens across the states.

State Policies & Collaborations • Triple Aim: improve patient experience, cost control and population health. • Medicaid tobacco cessation should be low hanging fruit. A joint responsibility of Medicaid and public health. Often in the same department. • Medicaid generally covers cessation benefits already. • Examples of strong state initiatives involved Medicaid public health collaborations. • But agencies are typically in silos, with separate jurisdictions even when they are in the same department.

Factors Affecting Cessation Utilization • Determinants of medication use (prescription fills per smoker) for every state from 2010 -14 (n= 5 * 51) • Traditional analyses based on coverage policies, but they might not be main determinants. • Independent variables included: – Medicaid coverage of NRTs, bupropion, varenicline – Coverage restrictions (copays, preauthorization, requirement for counseling) – Cigarette taxes, smoke-free laws – Overall smoking prevalence – Quitline medication availability

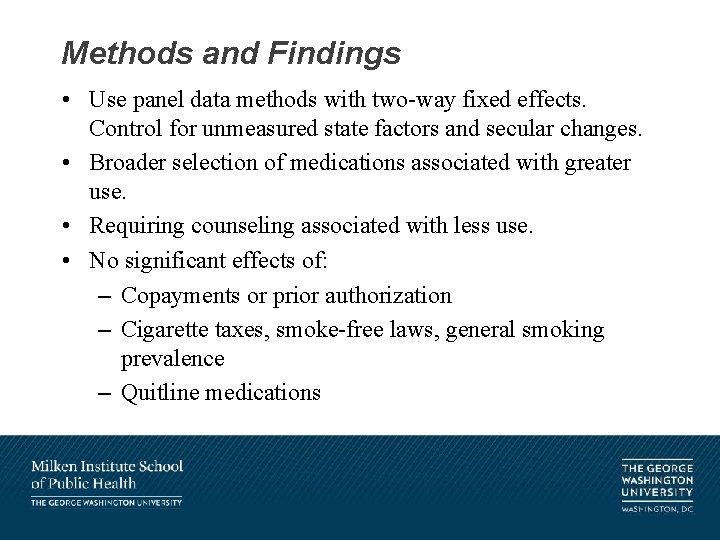

Methods and Findings • Use panel data methods with two-way fixed effects. Control for unmeasured state factors and secular changes. • Broader selection of medications associated with greater use. • Requiring counseling associated with less use. • No significant effects of: – Copayments or prior authorization – Cigarette taxes, smoke-free laws, general smoking prevalence – Quitline medications

Limitations & Issues • Could not account for special state initiatives • Tested variants due to measurement uncertainties about managed care policies and medications (bupropion). Findings are robust and consistent. • Somewhat puzzled by lack of significant effects of copayments, cigarette taxes, smokefree laws.

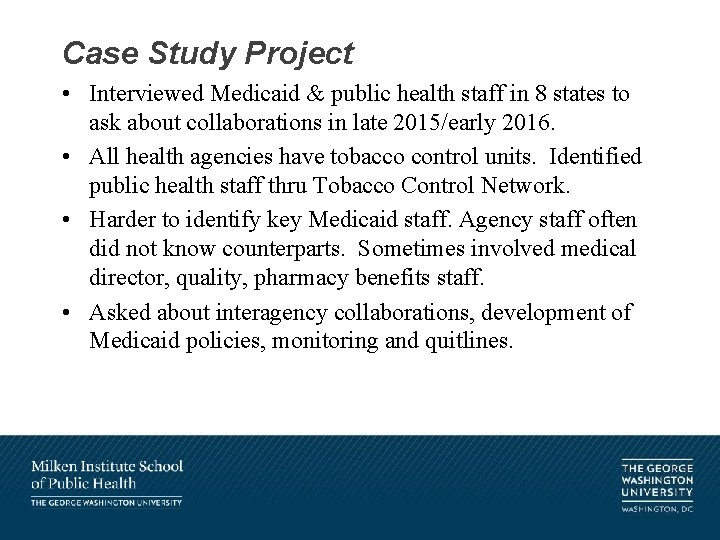

Case Study Project • Interviewed Medicaid & public health staff in 8 states to ask about collaborations in late 2015/early 2016. • All health agencies have tobacco control units. Identified public health staff thru Tobacco Control Network. • Harder to identify key Medicaid staff. Agency staff often did not know counterparts. Sometimes involved medical director, quality, pharmacy benefits staff. • Asked about interagency collaborations, development of Medicaid policies, monitoring and quitlines.

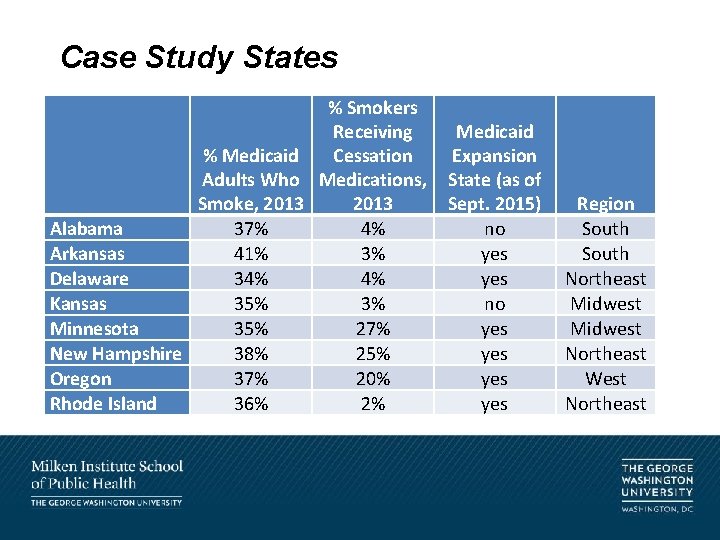

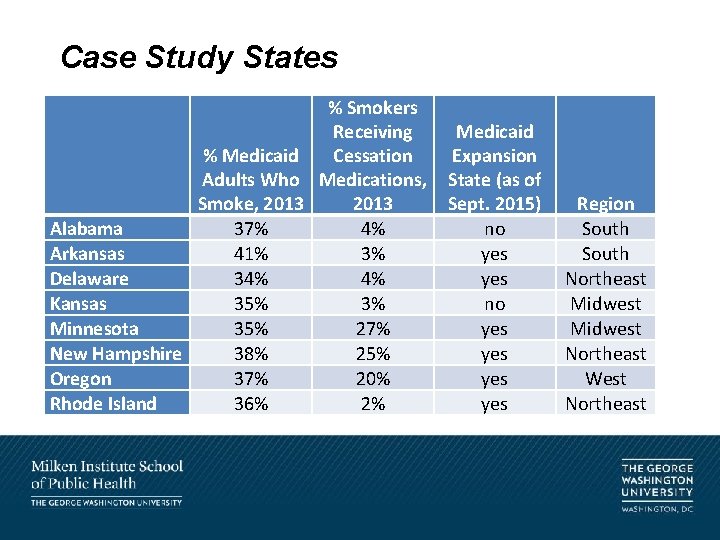

Case Study States % Smokers Receiving % Medicaid Cessation Adults Who Medications, Smoke, 2013 Alabama 37% 4% Arkansas 41% 3% Delaware 34% 4% Kansas 35% 3% Minnesota 35% 27% New Hampshire 38% 25% Oregon 37% 20% Rhode Island 36% 2% Medicaid Expansion State (as of Sept. 2015) no yes yes yes Region South Northeast Midwest Northeast West Northeast

Not Much Collaboration • Generally little or no collaboration. No joint projects. • Limited high level or external leadership. • Medicaid agencies developed coverage policies without input from health dept. • Public health agencies operated tobacco prevention and education programs, but not really focused on Medicaid. • Main area of interaction was quitlines, run by health dept, • Some wanted Medicaid funding. Many callers are Medicaid recipients. Usually did not get Medicaid funding.

Example of Different Mindsets • In Minnesota, Medicaid said it covered quitline medications. Quitline disagreed and it got no support. • Discrepancy explained by what “coverage” means • Medicaid had policy to pay for medications provided by quitline to Medicaid beneficiaries if quitline used an approved pharmacy. Had done so in the past. • Quitline changed contractor. New contractor did not have approved pharmacy. • To Medicaid “coverage” meant there was a policy to pay under right circumstances. • To quitline, “coverage” meant Medicaid actually pays.

What Can States Do? • We are still in progress to understand why some states are doing better than others. • Ultimate goals are to encourage providers to help with cessation (5 As) and engage patients to quit successfully. • But a first step is to make smoking cessation a priority for Medicaid, managed care organizations and to work with public health agencies. • Another step is to begin to develop measures to monitor efforts and outcomes. • CDC and CMS beginng to encourage states to focus on smoking cessation, particularly thru CDC’s 6|18 Initiative.

Thinking More Broadly • Triple Aim for health policy: (1) improve patient experience of care (quality and satisfaction), (2) limit health care costs and (3) improve population health. • How can we better align health care policy goals with public health goals? • Can health policy and public health officials work together to improve population health? What are roles of primary (community) and secondary (clinical) prevention? • How can we increase engagement by clinicians, patients and communities?

Support • Supported by National Cancer Institute grant R 15 CA 176600 and Robert Wood Johnson Evidence 4 Action grant.

References • Ku, L. , Brantley, E. , Bysshe, T. , Steinmetz, E. , Bruen, B. How Medicaid and Other Public Policies Affect Utilization of Tobacco Cessation, Preventing Chronic Diseases, 2016. • Ku L, Bruen B, Steinmetz E & Bysshe T. Medicaid Tobacco Cessation: Big Gaps Remain in Efforts to Get Smokers to Quit, Health Affairs, 2016 Jan. 35(1) • Richard P, West K & Ku L. The Return on Investment of a Medicaid Tobacco Cessation Initiative in Massachusetts. PLo. S One. 2012; 7(1).