3 Ethnographic methods Entering the field Doing participant

- Slides: 12

3. Ethnographic methods: Entering the field. Doing participant observation. Writing fieldnotes Qualitative Research Methods in Nationalism and Ethnic Studies 2019 Central European University Nationalism Studies Margit Feischmidt

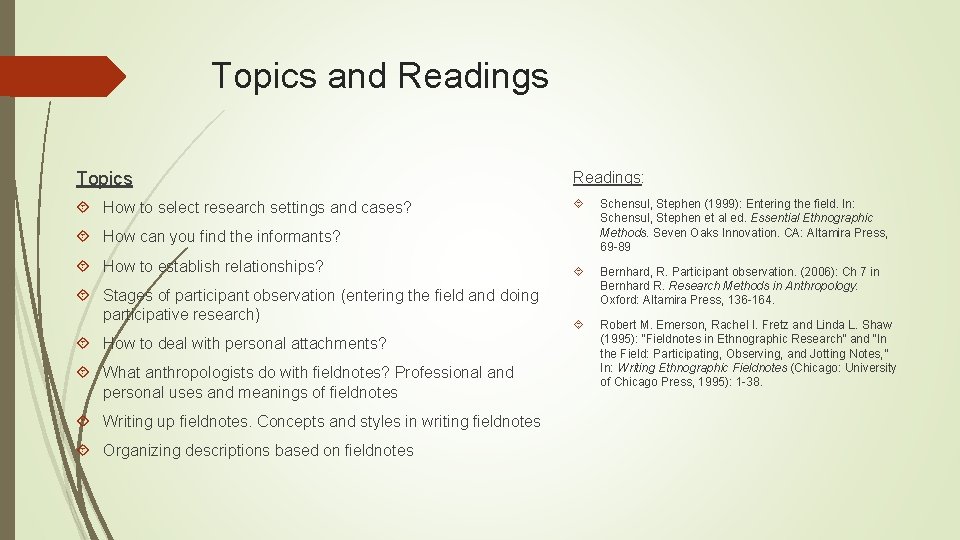

Topics and Readings Topics Readings: How to select research settings and cases? Schensul, Stephen (1999): Entering the field. In: Schensul, Stephen et al ed. Essential Ethnographic Methods. Seven Oaks Innovation. CA: Altamira Press, 69 -89 Bernhard, R. Participant observation. (2006): Ch 7 in Bernhard R. Research Methods in Anthropology. Oxford: Altamira Press, 136 -164. Robert M. Emerson, Rachel I. Fretz and Linda L. Shaw (1995): “Fieldnotes in Ethnographic Research” and “In the Field: Participating, Observing, and Jotting Notes, ” In: Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995): 1 -38. How can you find the informants? How to establish relationships? Stages of participant observation (entering the field and doing participative research) How to deal with personal attachments? What anthropologists do with fieldnotes? Professional and personal uses and meanings of fieldnotes Writing up fieldnotes. Concepts and styles in writing fieldnotes Organizing descriptions based on fieldnotes

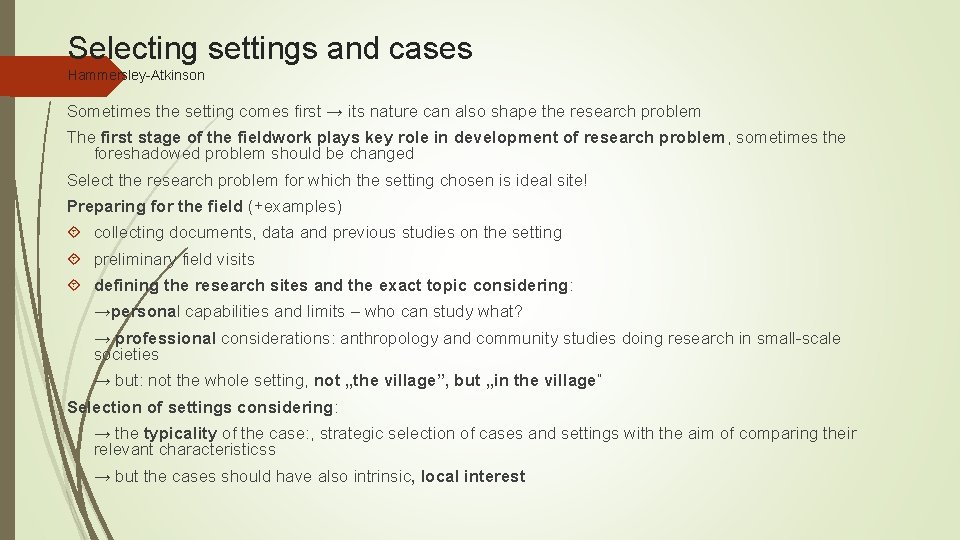

Selecting settings and cases Hammersley-Atkinson Sometimes the setting comes first → its nature can also shape the research problem The first stage of the fieldwork plays key role in development of research problem, sometimes the foreshadowed problem should be changed Select the research problem for which the setting chosen is ideal site! Preparing for the field (+examples) collecting documents, data and previous studies on the setting preliminary field visits defining the research sites and the exact topic considering: →personal capabilities and limits – who can study what? → professional considerations: anthropology and community studies doing research in small-scale societies → but: not the whole setting, not „the village”, but „in the village” Selection of settings considering: → the typicality of the case: , strategic selection of cases and settings with the aim of comparing their relevant characteristicss → but the cases should have also intrinsic, local interest

The field and the fieldwork The field Natural and, non-laboratory setting where activities in which the researcher is interested take place The fieldwork 1) Engagement in direct learning through physical and social involvement in the field setting 2) Personal! Researchers transform themselves into primary instruments of data collection, consequences: Our influence on the setting – Try to limit! How? Careful and ongoing reflection over your influence and relationships 3) Experiencing by observing, participating in conversations, daily activities and 4) Transforming these experiences into data through recording and interpreting observations

Advantages and validity of the ethnographic work Reduces the problem of reactivity Helps us to raise and answer sensible questions Gives us an intuitive understanding of what’s going on in a site and allows us to speak about the meaning of our data Many research problems can not be addressed by anything except participant observation EXAMPLES

Entering the field (Steps of your fieldwork) 1. Conceptual preparation for the fieldwork. Questions we take with us 2. Leaving our homes (communities, institutional settings, familiar behavioral and cognitive patterns) → enter an other social world or the same with a different approach 3. Take written documentation about yourself and the project and obtain formal permission 4. Spend some time to know the physical and social layout of your field 5. Learn how to function in the new setting (learn the language, cultural patterns, rules guiding social relationships) 6. Establish contact with people knowledgeable about the local setting 7. Identify and conduct interviews with local gatekeepers 8. Carry out observation from distance 9. Obtain introduction through local gatekeepers to others in the field 10. Gain direct involvement in the research setting with the assistance of gatekeepers and key informants; focus more clearly on the subject

Establishing relationships Good ethnographers build relationship quickly, but to a certain extend everybody can learn how to do this Building trust is not only a professional question → our entry is very similar to nonresearchers’ entry to any new situation Importance of reciprocity in field relations, think about what you can offer (time, knowledge, expertise, small favors) “the cover story” – what we tell about ourselves and about our project – be confident, but there are some restrictions (What should we avoid to tell? Ex. study of ethnicity, nationalism) Whom we meet firstly? The marginal men, who hope to promote their own interests or enhance their personal status by befriending the researcher, Schensul: skeptic, MF: useful Gaining access to important social events and further people ENTERING THE FIELD: WHAT TO SAY ABOUT YOURSELVE? WHOM TO CONTACT?

Local gatekeepers Obtain formal (official) permission Contact local scholars and authorities Different approaches to continue: →bottom-up (starting among ordinary people and finishing by the authorities and power holders) → top-down (starting in the director’s or principal’s bureau) Gatekeepers: officialy or informaly control certain resources and the respective knowledge – ex. the mayor, head of the minority organization What to do with the gatekeepers? describe the project to them ask for their help interview them about themselves and the community ask them for further help maintain regular communication with them WHO IS THE OFFICIAL AND THE UNOFFICIAL GATEKEEPER IN YOUR WORK?

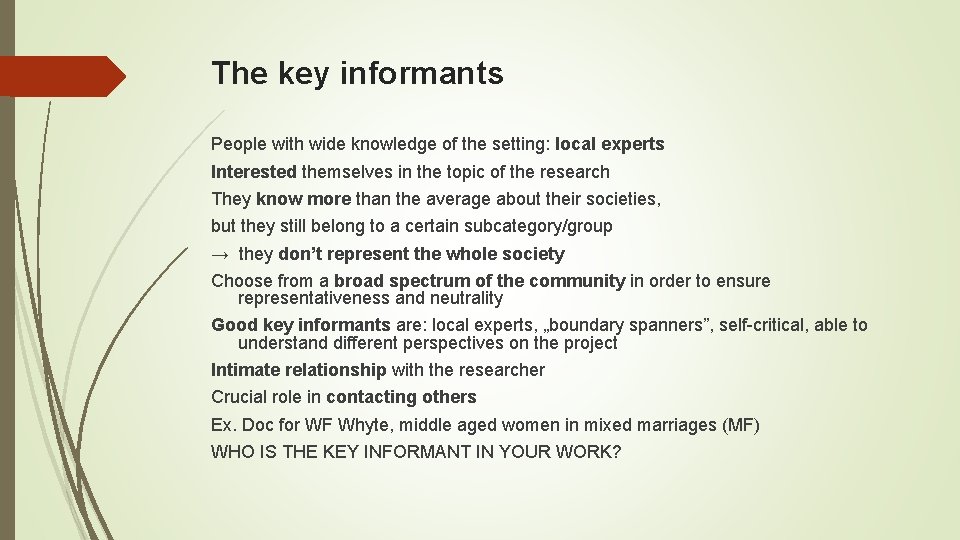

The key informants People with wide knowledge of the setting: local experts Interested themselves in the topic of the research They know more than the average about their societies, but they still belong to a certain subcategory/group → they don’t represent the whole society Choose from a broad spectrum of the community in order to ensure representativeness and neutrality Good key informants are: local experts, „boundary spanners”, self-critical, able to understand different perspectives on the project Intimate relationship with the researcher Crucial role in contacting others Ex. Doc for WF Whyte, middle aged women in mixed marriages (MF) WHO IS THE KEY INFORMANT IN YOUR WORK?

Writing fieldnotes. General advices (Emerson) 1. Document closely the learning process of your field, the discovery, rather than a later point in light of some final, ultimate interpretation of their meaning 2. Write about your first impressions, a range of incidents and interactions 3. As fieldwork progresses – be more focused on issues, interactions of the same type 4. The “microscopic” commitment in observation events, note every fine detail → close, detailed reports on interactions (to grasp the active “doing” of social life) 5. Take fieldnotes in ways that capture and preserve different indigenous meanings - “polivocality”

Practical advices: the content of fieldnotes (Emerson) Jottings keywords + quotations of action and talk, very concretely (who does, with whom, what do they say etc. ) write jotting that evoke memoires concrete sensatory details (specific circumstances, emotions) avoid generalizations Writing up fieldnotes I. withdraw for writing every day (every time people forget and simplify experience) type it in your computer and not in your copybook when turning back from the field a synthesis is needed

Emerson: Practical advices – writing strategies Describing basic settings Focus on description rather than argumentation Use concrete sensatory details, that the image can be clearly visualized Avoid evaluative adjectives and verbs, and never permit a label Use visual documentation (photography, short video) Presenting dialogue between people: phrases quoted verbatim should be placed between quotation marks, others should be recorded as indirect quotations, members own stories, descriptions of their experiences, supplement the fieldnotes by tape recordings Characterizing individuals who appear in the account, showing what and how that person talks, acts and relates to others