121806 JeanPaul Sartre 1905 1980 1946 some of

![The Cartesian cogito F F [Many of our critics charge us] with imprisoning the The Cartesian cogito F F [Many of our critics charge us] with imprisoning the](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/1b43ef7f93bbfe43bc3dfb01d44b387f/image-34.jpg)

![The Unavoidability of Choice and the Call of Freedom F F [W]hat is not The Unavoidability of Choice and the Call of Freedom F F [W]hat is not](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/1b43ef7f93bbfe43bc3dfb01d44b387f/image-38.jpg)

- Slides: 42

12/18/06 Jean-Paul Sartre (1905 -1980) (1946)

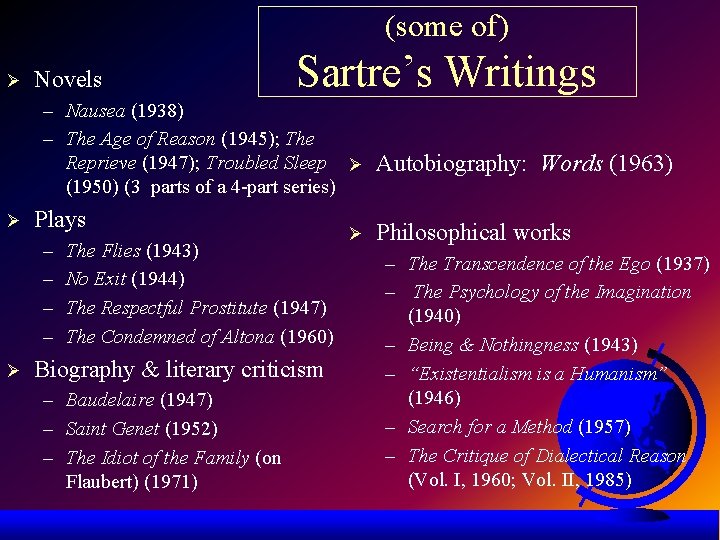

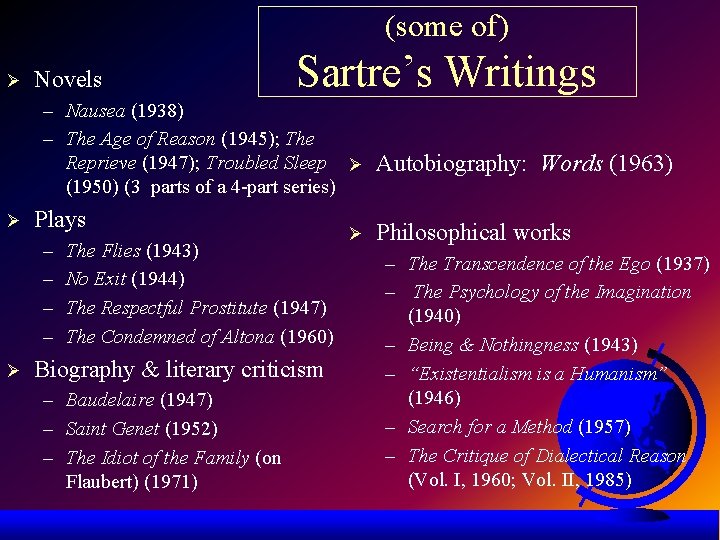

(some of) Ø Novels Sartre’s Writings – Nausea (1938) – The Age of Reason (1945); The Reprieve (1947); Troubled Sleep Ø Autobiography: Words (1963) (1950) (3 parts of a 4 -part series) Ø Plays – – Ø The Flies (1943) No Exit (1944) The Respectful Prostitute (1947) The Condemned of Altona (1960) Biography & literary criticism – Baudelaire (1947) – Saint Genet (1952) – The Idiot of the Family (on Flaubert) (1971) Ø Philosophical works – The Transcendence of the Ego (1937) – The Psychology of the Imagination (1940) – Being & Nothingness (1943) – “Existentialism is a Humanism” (1946) – Search for a Method (1957) – The Critique of Dialectical Reason (Vol. I, 1960; Vol. II, 1985)

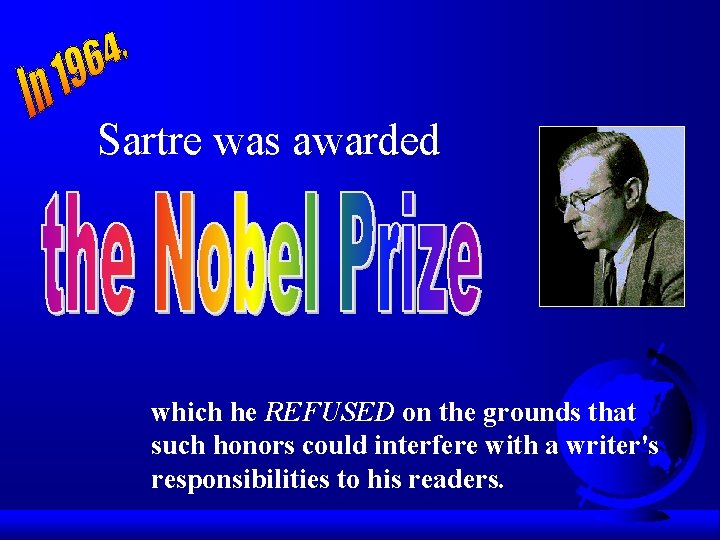

Sartre was awarded which he REFUSED on the grounds that such honors could interfere with a writer's responsibilities to his readers.

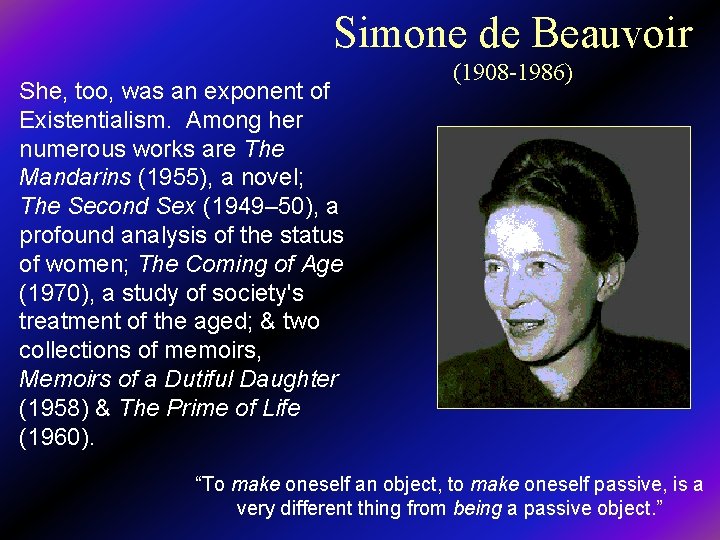

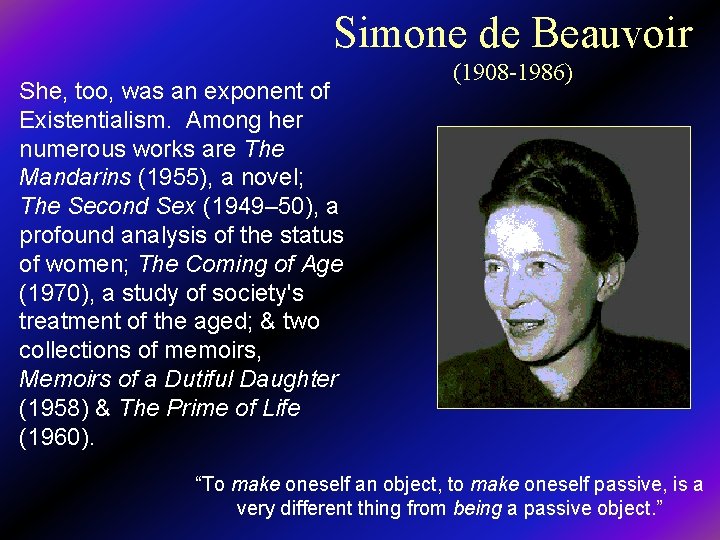

Sartre did not believe in “bourgeois marriage, ” but he had an intimate life partnership from the late 1920 s until his death in 1980 with. .

Simone de Beauvoir She, too, was an exponent of Existentialism. Among her numerous works are The Mandarins (1955), a novel; The Second Sex (1949– 50), a profound analysis of the status of women; The Coming of Age (1970), a study of society's treatment of the aged; & two collections of memoirs, Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter (1958) & The Prime of Life (1960). (1908 -1986) “To make oneself an object, to make oneself passive, is a very different thing from being a passive object. ”

So, Sartre, What is Existentialism?

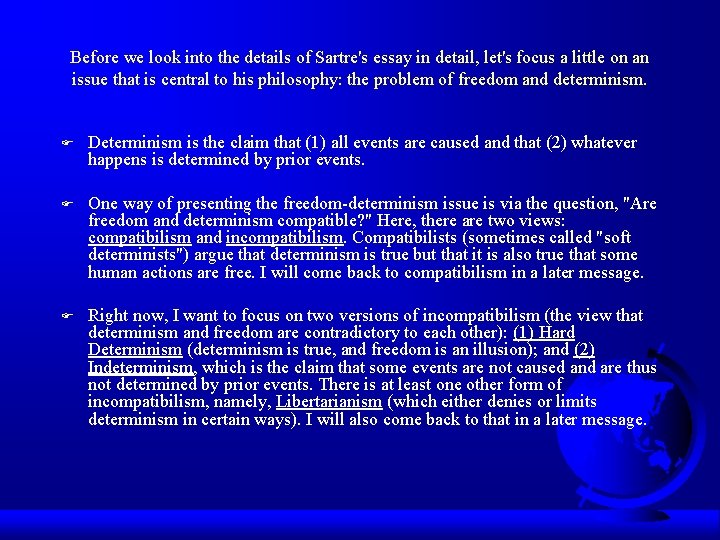

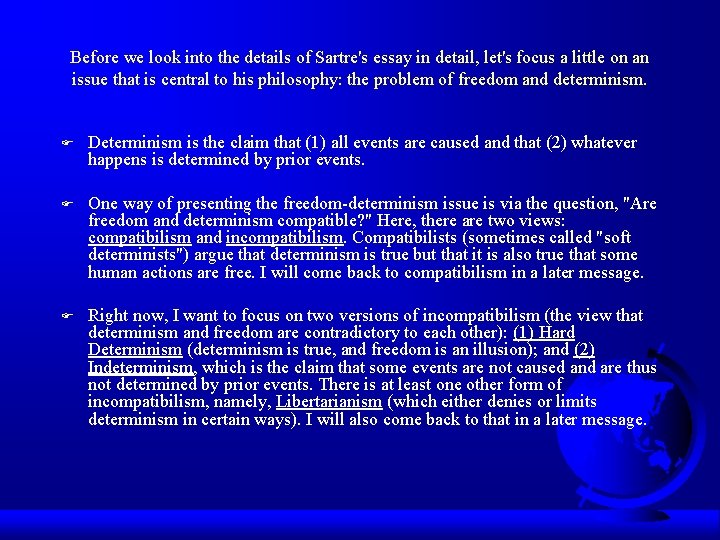

Before we look into the details of Sartre's essay in detail, let's focus a little on an issue that is central to his philosophy: the problem of freedom and determinism. F Determinism is the claim that (1) all events are caused and that (2) whatever happens is determined by prior events. F One way of presenting the freedom-determinism issue is via the question, "Are freedom and determinism compatible? " Here, there are two views: compatibilism and incompatibilism. Compatibilists (sometimes called "soft determinists") argue that determinism is true but that it is also true that some human actions are free. I will come back to compatibilism in a later message. F Right now, I want to focus on two versions of incompatibilism (the view that determinism and freedom are contradictory to each other): (1) Hard Determinism (determinism is true, and freedom is an illusion); and (2) Indeterminism, which is the claim that some events are not caused and are thus not determined by prior events. There is at least one other form of incompatibilism, namely, Libertarianism (which either denies or limits determinism in certain ways). I will also come back to that in a later message.

Here a couple of arguments for (1) Hard Determinism and for (2) Indetrminism Here is an argument for Hard Determinism: 1. Whatever happens is determined by prior events. 2. I act freely only if I am able to act otherwise. 3. If my action is determined (Premise 1), then I am not able to act otherwise. ------------------------------------------------4. I never act freely. And here is an argument based on Indeterminism, which also seems to rule out the reality of freedom: 1. If determinism is true, we can never do other than we do; so we are not free. 2. If indeterminism is true, then some events (and actions) are random. 3. If some events or actions are random, then we are not their authors; so we are not free. 4. Either determinism or indeterminism is true. ------------------------------------------------------5. We never act freely. Any thoughts on these arguments? What would Sartre (a radical libertarian incompatibilist) say in response to them?

Continuing on the freedom-determinism theme, here is some commentary on the perspectives of Soft Determinism (Compatibilism) and Libertarianism (one kind of Incompatibilism). (Sartre is a Libertarian on this issue. ) F Soft Determinism: Determinism and freedom are compatible. All events - including human actions are caused by prior events. However, freely chosen human actions are caused by the actor's character, beliefs, and desires (events and causes internal to the actor). As long as one's chosen actions are not caused by external coercion or some kind of internal pathological compulsion, those actions are "free. " F Libertarianism: Determinism and freedom are incompatible. If all actors and all actions are events, and if all events are caused by prior events, then there is no freedom. However, a human actor - a self - is not an event. It is a "substance, " a primary reality, which is the "uncaused cause" of its own actions. Actions are caused, but not all actions are caused by prior "events. " Some actions - the ones chosen by the self - are caused by the self, which is not an "event" but a "substance. " The self is not caused (determined) to choose as it does. It chooses on the basis of its own free reasoning and deliberation (remember Aristotle's discussion of this? ). As some critics have pointed out, this theory does present the "self" as something of a minor god (since God is also often depicted as the absolutely free creator - the ultimate Uncaused Cause - of the existence of the cosmos). F Sartre supports the Libertarian position. I hope everyone sees that as they read his essay on Existentialism. F That's all too brief and perhaps unclear. I hope to supplement this later (if I can find the time!). F Each of the (four) approaches to the freedom-determinism issue has its problems. Can you see what they might be? (The four approaches: Hard Determinism, Indeterminism, Soft Determinism, and Libertarianism. ) [See my earlier bbd message on this. See also the links under Supplementary Study Materials icon item 7. 4. ]

OK, Let's get into Sartre's essay on the nature of Existentialism….

“Existence” is Prior to “Essence” Text, 481 -2

S’s “phenomenological” starting point (What is phenomenology? ) An approach to reality from the standpoint of subjectivity (consciousness) If I approach reality from that point of view, what do I find?

I find a difference v between subjects & objects, v between persons & things, v between beings that are conscious & beings that are not conscious. What is the difference?

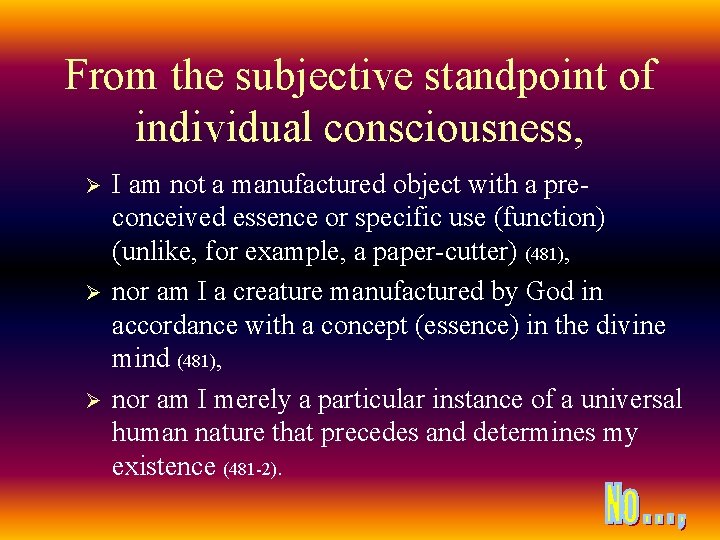

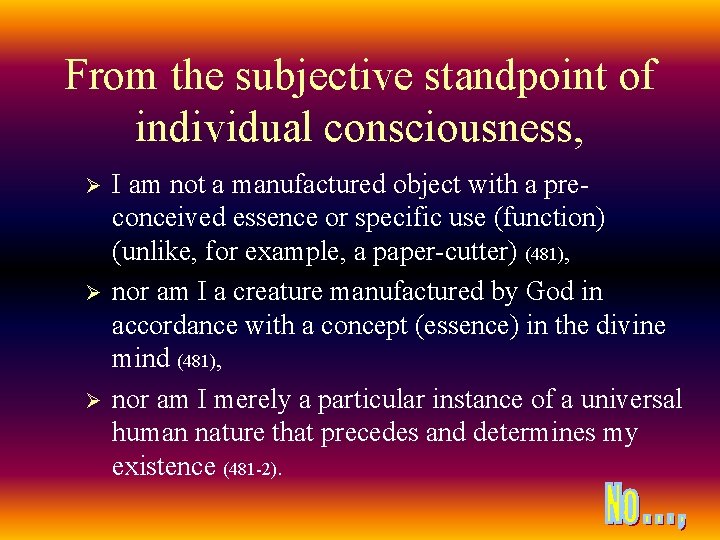

From the subjective standpoint of individual consciousness, Ø Ø Ø I am not a manufactured object with a preconceived essence or specific use (function) (unlike, for example, a paper-cutter) (481), nor am I a creature manufactured by God in accordance with a concept (essence) in the divine mind (481), nor am I merely a particular instance of a universal human nature that precedes and determines my existence (481 -2).

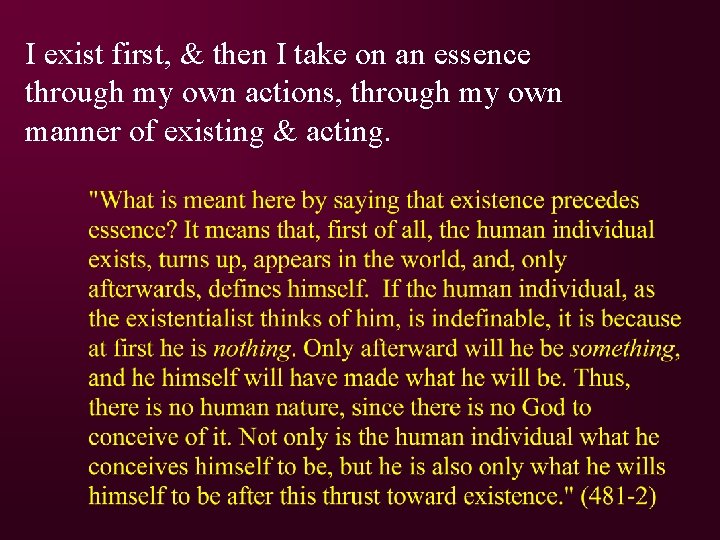

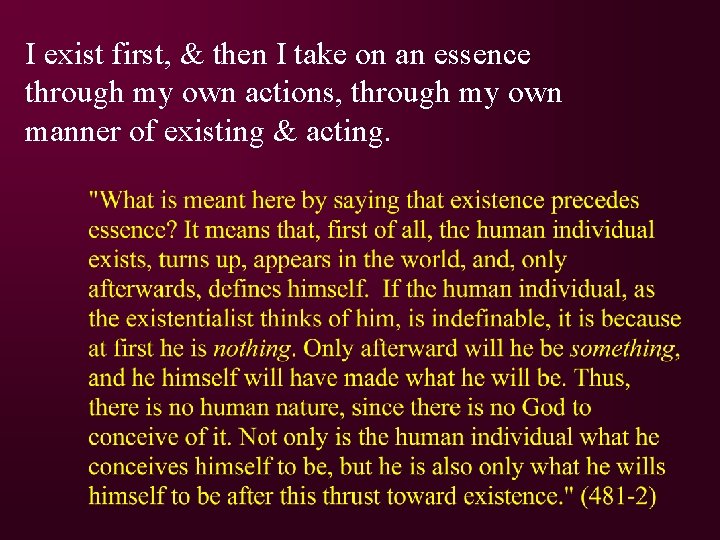

I exist first, & then I take on an essence through my own actions, through my own manner of existing & acting.

Self-Creation & Personal Responsibility Text, 482

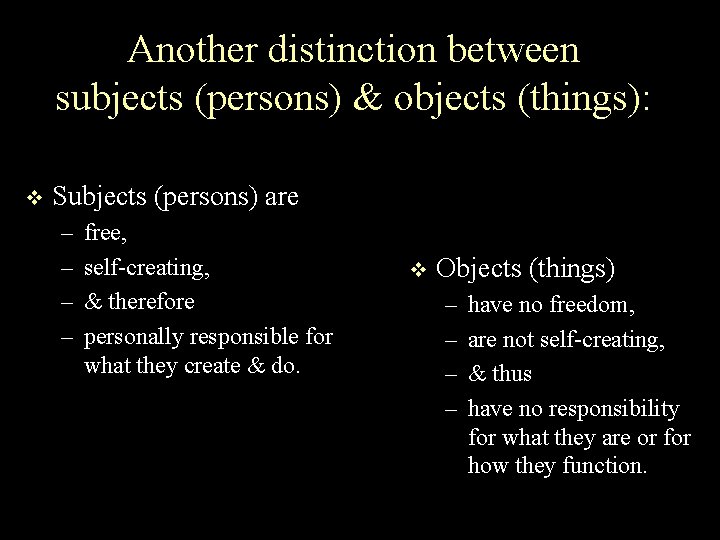

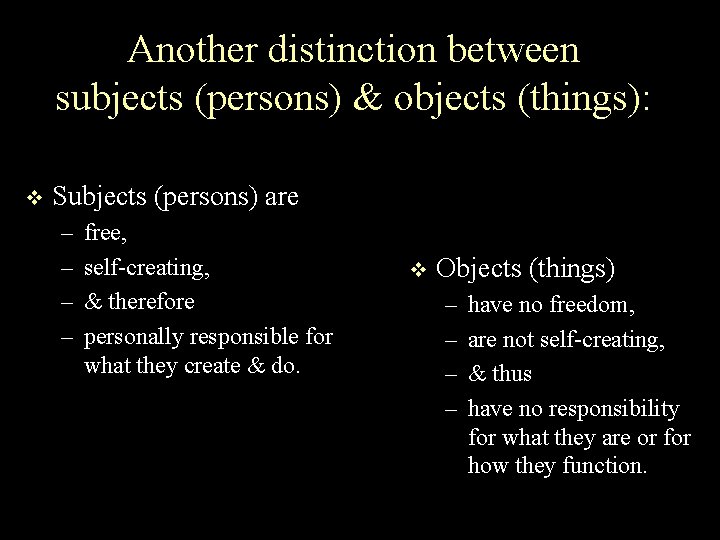

Another distinction between subjects (persons) & objects (things): v Subjects (persons) are – – free, self-creating, & therefore personally responsible for what they create & do. v Objects (things) – – have no freedom, are not self-creating, & thus have no responsibility for what they are or for how they function.

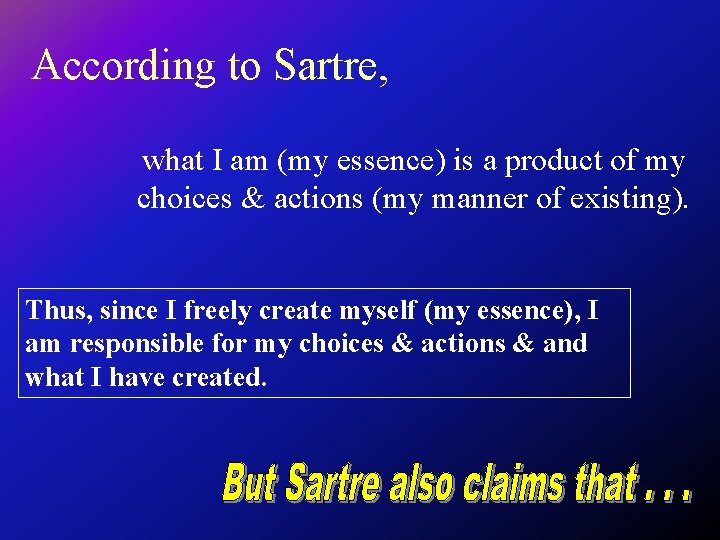

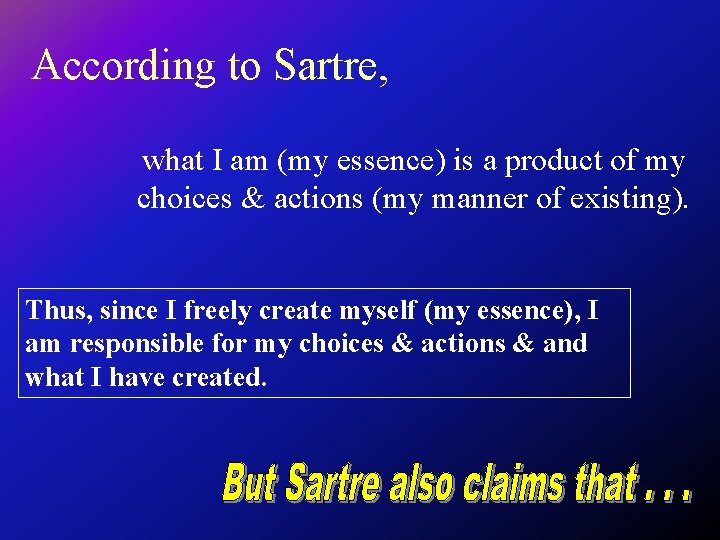

According to Sartre, what I am (my essence) is a product of my choices & actions (my manner of existing). Thus, since I freely create myself (my essence), I am responsible for my choices & actions & and what I have created.

“Therefore, I am responsible for myself and for everyone else. ”

According to Sartre, if I recognize that I am not made to be what I am but rather freely choose my own “essence, ” F that what I am is my own responsibility because my self is my own creation, F that, through my choices, I become responsible not only for myself but also for [all? ] others, & F that I cannot look to God for guidance in this process since God does not exist, F

Anguish, Forlornness, & Despair Text, 482 -6

Existential Anguish a response to the burden of responsibility

What’s wrong with the following claims? F “But everyone doesn’t act that way” (in response to the question, “What if everyone acted that way? ”). F “An angel of God or God Himself commanded me to do it. ” F “My anguish keeps me from acting. ”

Existential Forlornness a response to the non-existence of God

Implications of the nonexistence of God: F No foundation for objective & absolute values. F All values are human creations. F Man is “condemned to be free. ” F We are alone, with no justifications & no excuses. Dostoevsky: "If God does not exist, then everything is permitted. "

Looking for answers Ø How to resolve moral dilemmas: A student’s struggle with conflicting moral obligations. (484 -5) Ø How to define the meaning of one’s life: A young priest’s interpretation of the “signs. ” (485) How do these examples illustrate Sartre’s explanation of existential forlornness?

Existential Despair a response to the unreliability of others (relying on what is subject to one’s own will, not on things or persons external to one’s will)

Comment (and Questions) on Sartre's Atheism q There is a difference between Sartre's atheism and theism of philosophers like Anselm of Canterbury, or Thomas Aquinas, or Rene Descartes: The latter offer *philosophical arguments* in support of their belief in the reality of God. Sartre offers no arguments or reasons in support of his atheism. He has been called a "postulatory atheist, " which means that he simply "postulates" (assumes without proof) the non-existence of God and goes on from there. If God does not exist, he reasons, then we are on our own, and we must face up to the fact that a life without God, if lived honestly, is a life full of anxiety, forlornness, and despair. If we don't face up to that, then we are not taking the non-existence of God seriously enough. We are not facing up to the full and real implications of being completely on our own in a meaningless universe. If we don't face up to that, then we are in serious denial - we are, truly, kidding ourselves. q Sartre never gives any reasons for thinking that God does not exist. He does not find God present in his experience (phenomenologically considered). He just *postulates* the nonexistence of God. He feels no obligation to prove that God does not exist. He probably thinks that the *burden of proof* for the *existence* of God is on theists, and he no doubt does not find any of theistic arguments (e. g. , of Anselm, Aquinas, Descartes, etc. ) persuasive. q However, Sartre is an atheist with a difference. He is not happy that God does not exist. Without God, we must live in anxiety, forlornness, and despair -- on our own, with no ultimate guidance, and also with no excuses for ourselves. Each one of us finds her/himself totally responsible for her/his existence. q Wouldn't many theists *agree* with Sartre on the existential implications of the non- existence of God (without, of course, agreeing with him that God does not exist)? In a way, doesn't Sartre (perhaps contrary to his intentions) give aid and comfort to theism?

-7 6 8 4 , t x Te A Philosophy of Action

A Philosophy of Action F F F Actually, things will be as humanity will have decided they are to be. Does that mean that I should withdraw from life, retreat into inaction? No. First, I should engage myself; then act on the old saying, “Nothing ventured, nothing gained. ” Nor does it mean that I shouldn’t belong to a [political] party, but rather that I shall have no illusions and shall do what I can. For example, suppose I ask myself, “Will true socialism ever come about? ” All I can know is that I’m going to do everything in my power to bring it about. Beyond that, I can’t count on anything. There are people who say, “Let others do what I can’t do. ” Existentialism says the very opposite. It declares, “There is no reality except in action. ” Moreover, it goes further, since it adds, “Man is nothing but his project; he exists only to the extent that he fulfills himself; he is therefore nothing but the totality of his acts, nothing but his life. ” According to this, we can understand why our philosophy horrifies certain people. Quite often, the only way they can bear their misery is to think, “Circumstances have been against me. What I’ve been and done doesn’t show my true worth. To be sure, I’ve had no great love, no great friendship, but that’s because I haven’t met a man or woman who was worthy. The books I’ve written haven’t been very good because I haven’t had enough time to spend on them. I haven’t had children to devote myself to because I didn’t find a man with whom I could have spent my life. So there remains within me, unused but quite alive, a host of tendencies, inclinations, and possibilities that one wouldn’t infer from the mere series of things I’ve done. ” Now, for the existentialist, there is really no love other than one that manifests itself in a person’s being in love. There is no genius other than one that is expressed in works of art. The genius of [Marcel] Proust [1871 -1922] is the sum of his works; the genius of [Jean] Racine [1639 -1699] is his series of tragedies. Outside of that, there is nothing. Why say that Racine could have written another tragedy when he didn’t write it? A man is engaged in life, leaves his mark on it, and outside of that there is nothing. To be sure, this may seem a harsh thought to someone whose life hasn’t been a success. But. . . it prompts people to understand that reality alone is what counts, that dreams, expectations, and hopes do no more than to define a man as a disappointed dream, as miscarried hopes, as vain expectations — in other words, to define him negatively and not positively. However, when we say, “You are nothing but your life, ” that does not necessarily mean that the artist will be judged solely on the basis of his works of art. A thousand other things will contribute toward defining him. What we mean is that a man is nothing but a series of undertakings, that he is the sum, the organization, the collection of the relationships that make up these undertakings. .

A Philosophy of Action F F F In our works of fiction, we write about people who are soft, weak, cowardly, and sometimes even downright bad. Our fiction is often called pessimistic, but not because the characters depicted are soft, weak, cowardly, or bad. If we were to say, as [Emile] Zola [1840 -1902] did, that they are that way because of heredity, the workings of the environment, society, or because of biological or psychological determinism, our critics would be reassured and comforted. They would then say, “Well, that’s what we’re like; no one can do anything about it. ” But when an existentialist writes about a coward, he says that this coward is responsible for his cowardice. He’s not like that because he has a cowardly heart or lung or brain; he’s not like that because of his physiological makeup. No, he’s like that because he has made himself a coward by his [own] actions. There’s no such thing as a cowardly constitution. There are nervous constitutions; there is poor blood, as the common people say; and there are strong constitutions. But the man whose blood is poor is not a coward for that reason. What makes cowardice is the act of renouncing or yielding. A [physiological] constitution is not an act. The coward is defined on the basis of the acts he performs. People feel, in a vague sort of way, that this coward we’re talking about is guilty of being a coward, and the thought frightens them. What people would like is for a coward or a hero to be born that way. . That’s what people really want to think. If you’re born cowardly, you may set your mind perfectly at rest. There’s nothing you can do about it. You’ll be cowardly all your life, whatever you may do. If you’re born a hero, you may set your mind just as much at rest. You’ll be a hero all your life. You’ll drink like a hero and eat like a hero. What the existentialist says is that the coward makes himself cowardly, that the hero makes himself heroic. There’s always a possibility for the coward not to be cowardly any more and for the hero to stop being heroic. What counts is total involvement. Some one particular action or set of circumstances is not total involvement. .

Existential Subjectivity 8 7 8 Te 4 , t x

![The Cartesian cogito F F Many of our critics charge us with imprisoning the The Cartesian cogito F F [Many of our critics charge us] with imprisoning the](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/1b43ef7f93bbfe43bc3dfb01d44b387f/image-34.jpg)

The Cartesian cogito F F [Many of our critics charge us] with imprisoning the human individual in his private subjectivity. . The subjectivity of the individual is indeed our point of departure, and this for strictly philosophical reasons. . There can be no other truth to start off from than this: I think; therefore, I exist. [1] There we have the absolute truth of consciousness becoming aware of itself. Every theory that removes man from the moment in which he becomes aware of himself is, at its very beginning, a theory that hides truth, for outside the Cartesian cogito, all views are only probable, and a theory of probability that is not bound to a truth [that is certain] dissolves into thin air. In order to describe the probable, you must have a firm hold on the truth. Before there can be any truth whatsoever, there must be an absolute truth. And this one [the cogito] is simple and easily arrived at; it’s on everyone’s doorstep; it’s [just] a matter of grasping it directly. Also, this theory is the only one that gives the human individual dignity, the only one that does not reduce him to an object. The effect of all [forms of philosophical] materialism is to treat all humans, including the one who is philosophizing, as objects, that is, as a series of determined reactions in no way distinguished from the collection of qualities and phenomena that constitute a table or a chair or a stone. Existentialists definitely wish to establish the human realm as a set of values distinct from the material realm.

Self and others — intersubjectivity But the subjectivity that we have thus arrived at, and which we have claimed to be. . . [fundamentally real], is not a strictly individual [or private] subjectivity, for we have shown that one discovers in the cogito, not only oneself, but others as well. . [T]hrough the I think, I reach my own self in the presence of others, and the others are just as real to me as my own self. So one who achieves self-awareness through the cogito also discovers all others, and he discovers them as the condition of his own existence. He realizes that he cannot be anything (in the sense that we say that someone is spiritual or nasty or jealous) unless others recognize it as such. In order to get any truth about myself, I must have contact with the other. The other is indispensable to my own existence, as well as to my knowledge about myself. This being so, in discovering my inner being, I discover the other at the same time, who appears before me as a free being that thinks and wills only for or against me. Hence, let us at once announce the discovery of a world that we shall call intersubjectivity. This is the world in which a person decides what he is and what others are.

The human condition F F Furthermore, although it is impossible to find in every person some universal essence that would be human nature, yet there does exist a universal human condition. It’s not by chance that today’s thinkers speak more readily of the human condition than of human nature. By condition they mean, more or less definitely, the fixed limits that outline humanity’s fundamental situation in the universe. Historical situations vary. A person may be born a slave in a pagan society or a feudal lord or a proletarian. What does not vary is the necessity for him (1) to exist in the world, (2) to be at work there, (3) to be there in the midst of other people, and (4) to be mortal there. These limits are neither subjective nor objective, or, rather, they have an objective and a subjective side. Objective because they are to be found everywhere and are recognizable everywhere [that is, they are universal]; subjective because they are lived and are nothing if a person does not live them, that is, if he does not freely determine his existence with reference to them. And though the ways in which people respond to the human condition may differ [from time to time, place to place, person to person]. . . , none of these responses is completely strange to me because they all appear as attempts either to pass beyond the limits of the human condition or to recede from them or to deny them or to adapt to them. Consequently, every human situation, no matter how individual it may be, has a universal value. .

The Unavoidability of Choice & the Call of Freedom (Text, 488)

![The Unavoidability of Choice and the Call of Freedom F F What is not The Unavoidability of Choice and the Call of Freedom F F [W]hat is not](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/1b43ef7f93bbfe43bc3dfb01d44b387f/image-38.jpg)

The Unavoidability of Choice and the Call of Freedom F F [W]hat is not possible is not to choose. I can always choose, and I ought to recognize that if I do not choose, I am still choosing. . [M]an is an organized project in which he himself is involved. Through his choice, he involves all humankind, and he cannot avoid making a choice: either he will remain unmarried, or he will marry without having children, or he will marry and have children. Anyhow, whatever he may do, it is impossible for him not to take full responsibility for the way he handles his problems. . Man makes himself. He isn’t completely defined at the start. In choosing his values, he makes himself, and the force of circumstances is such that he cannot abstain from choosing a set of values. . Existentialism defines the human situation as involving free choice, with no excuses and no hiding places. Everyone who takes refuge behind the excuse that he is driven by his passions, everyone who sets up any kind of determinism, is dishonest [that is, guilty of mauvaise foi, bad faith]. . I declare that freedom in every concrete circumstance can have no other aim than to want itself. If a person has once become aware that in his forlornness he creates and imposes values, he can no longer want but one thing, and that is freedom — freedom as the foundation of all values. That doesn’t mean than he wants it in the abstract. It means simply that the ultimate meaning of the acts of honest people is the quest for freedom as such. One who belongs to a communist or revolutionary union wants to reach concrete goals; these goals imply an abstract desire for freedom; but this freedom is wanted in something concrete. We want freedom for freedom’s sake and in every particular circumstance. And in wanting freedom, we discover that it depends entirely on the freedom of others, and that the freedom of others depends on ours.

Choice & Freedom F F F Of course, freedom as the definition of man does not depend on others, but as soon as there is involvement, I am obliged to want others to have freedom at the same time that I want my own freedom. I can take freedom as my goal only if I take that of others as a goal as well. Consequently, when, in all honesty, I’ve recognized that man is a being in whom existence precedes essence, that he is a free being who, in various circumstances, can want only his freedom, I have at the same time recognized that I can want only the freedom of others. [Does this last point follow necessarily from what S has said? ] Therefore, in the name of this will for freedom, which freedom itself implies, I may pass judgment on those who seek to hide from themselves the complete arbitrariness and the complete freedom of their existence. Those who hide their complete freedom from themselves out of a spirit of seriousness or by means of deterministic excuses, I shall cowards. Those who try to show that their existence is governed by necessity, when in fact it is. . . contingency [that marks] man’s appearance on earth, I shall call stinkers [salauds]. . I’m quite disturbed that’s the way it is; but if I’ve discarded God the Father, there has to be someone to invent values. You’ve got to take things as they are. Moreover, to say that we invent values means nothing. . . but this: life has no meaning prior to the individual’s existence. Before you come alive, life is nothing. It’s up to you to give it a meaning, and value is nothing. . . but the meaning that you choose. .

Existentialist Humanism Text, 489

Existentialist Humanism F [Existentialism is a certain kind of humanism, namely, a humanism that says that] man is constantly outside himself; in projecting himself, in losing himself outside of himself, he makes for man’s existing; and. . . it is by pursuing transcendent goals that he is able to exist; man, being this state of passing-beyond, and seizing upon things only as they bear upon this passing-beyond, is at the heart, at the center of this passing-beyond. There is no universe other than a human universe, the universe of human subjectivity. This connection between transcendence, as a constituent element of human existence — not in the sense that God is transcendent, but in the sense of passing-beyond — and subjectivity, in the sense that man is not closed in on himself but is always present in a human universe, is what we call existentialist humanism. Humanism, because we remind man that there is no law-maker other than himself, and that in his forlornness he will decide by himself; because we point out that man will fulfill himself as man, not in turning toward himself, but in seeking outside of himself a goal that is just this liberation, just this particular fulfillment. F Existentialism [that is, Sartre’s version of Existentialism] is nothing but an effort to draw out [and face up to] all the consequences of a coherent atheistic position. .

Finis

1980-1946

1980-1946 Sartre pensiero

Sartre pensiero Lycee jps

Lycee jps Essencia sartre

Essencia sartre Zaprta vrata

Zaprta vrata Jean paul sartre

Jean paul sartre Jean paul sartre zaprta vrata

Jean paul sartre zaprta vrata Existencialismo sartre

Existencialismo sartre Olivier sartre

Olivier sartre Crash course philosophy existentialism

Crash course philosophy existentialism Sartre adalah

Sartre adalah Sartre

Sartre Serialidade sartre

Serialidade sartre El ente nihilizador es el hombre

El ente nihilizador es el hombre Ospyciu

Ospyciu Modernisme kenmerken literatuur

Modernisme kenmerken literatuur Russian industrialization ap world

Russian industrialization ap world Poor law commission 1905

Poor law commission 1905 Umur basal adalah

Umur basal adalah Etisk realisme

Etisk realisme 1905-1828

1905-1828 Tradisjonell lyrikk

Tradisjonell lyrikk 1905 time

1905 time Mesaj expresionist apelativ

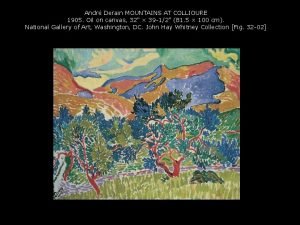

Mesaj expresionist apelativ Mountains at collioure

Mountains at collioure The poor law commission of 1905

The poor law commission of 1905 Vene revolutsioon 1905

Vene revolutsioon 1905 Pintor frances

Pintor frances Russian revolution of 1905 definition ap world history

Russian revolution of 1905 definition ap world history Carta da paz social 1946

Carta da paz social 1946 Maksud berkerajaan sendiri

Maksud berkerajaan sendiri 1946 born

1946 born 1946 römische zahlen

1946 römische zahlen Romania in perioada razboiului rece ppt

Romania in perioada razboiului rece ppt Ruang lingkup pkn di sd

Ruang lingkup pkn di sd Lbb 1946/00

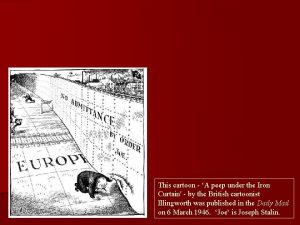

Lbb 1946/00 Joe iron curtain

Joe iron curtain Hungary inflation rate 1946

Hungary inflation rate 1946 Apakah tujuan ordinan pelajaran 1952 diwujudkan

Apakah tujuan ordinan pelajaran 1952 diwujudkan Iso 1946

Iso 1946 Nueva resurrección (1946)

Nueva resurrección (1946) Dator 1946

Dator 1946 Hungary inflation rate 1946

Hungary inflation rate 1946