University of Warwick Department of Sociology 201415 SO

- Slides: 14

University of Warwick, Department of Sociology, 2014/15 SO 201: SSAASS (Surveys and Statistics) (Richard Lampard) Clustering and Scaling (Week 19)

Distances. . . • Some quantitative techniques derive and/or use distances between variables, or distances between categories within variables, as the basis for the construction of maps or the division of items into sets of similar items. • These include multidimensional scaling, correspondence analysis, and cluster analysis.

Multidimensional scaling (MDS) • MDS is applied to a set of distances between all pairs of categories within a set of categories. • See Coxon (1982); Kruskal and Wish (1978)

Cluster analysis • In cluster analysis, distances between items (cases and/variables) are generated from the raw data, and then used to generate a categorisation of the items. • See Everitt (1993; see also later editions)

Classifying women’s occupations • Dale et al. (1985: see handout) used cluster analysis to develop an ‘alternative’ set of categories for women’s occupations.

The Cambridge Scale • The Cambridge Social Stratification scale was originally derived via the application of multidimensional scaling to occupation-based cross-tabulations matching the occupations of individuals and their ‘associates’. • It subsequently moved in the direction of using correspondence analysis (Prandy 1990; Prandy and Bottero 1998: 2. 6 - see handout).

‘Marriage and the Social Order’ • Prandy and Bottero (1998: handout) applied correspondence analysis to occupation-based cross-tabulations to locate occupations on a number of (highly correlated) occupational scales.

Correspondence analysis • Correspondence analysis in effect partitions the relationship in a cross-tabulation (and more specifically the chi-square statistic) into components reflecting a number of underlying dimensions (see Greenacre 2007). • More specifically, the difference between the distributions of values for two categories is split into components reflecting different underlying dimensions.

Association models • More recently the Cambridge scale and international equivalents have tended to use ‘association models’, which are a form of statistical model that echoes aspects of correspondence analysis. • See Goodman, L. A. 1986. ‘Some useful extensions to the usual correspondence analysis approach and the usual loglinear approach in the analysis of contingency tables (with comments)’, . Int. Statist. Rev. 54: 243 -309. • See also: http: //www. camsis. stir. ac. uk/

Evaluating the NS-SEC • In Rose and Pevalin (2003), various chapters (by Mills and Evans [see extract in handout], Coxon and Fisher, and Fisher) involved the application of cluster analysis, multidimensional scaling, and association models to the relationship between employment relations measures and occupational categories.

More references… • Cluster analysis: Hair, J. F. Jr. and Black, W. C. 2000. ‘Cluster Analysis’. In In L. Grimm and P. R. Yarnold (eds) Reading and Understanding More Multivariate Statistics. Washington, DC: APA Press. • Multidimensional scaling: Stalans, L. J. 1995. ‘Multidimensional scaling’. In L. Grimm and P. R. Yarnold (eds) Reading and Understanding Multivariate Statistics. Washington, DC: APA Press. • Correspondence analysis: Phillips, D. 1995. ‘Correspondence Analysis’, Social Research Update 7. (http: //sru. soc. surrey. ac. uk/SRU 7. html)

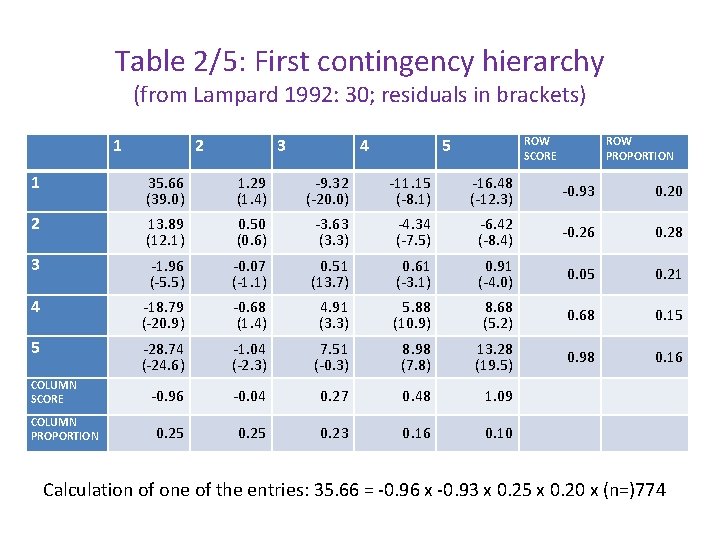

Row and column scores in correspondence analysis These are chosen in such a way that each successive dimension explains as much of the cross-tabulation’s chi-square statistic as possible, by contributing to a contingency hierarchy (see next slide) which is as small a chi-square ‘distance’ as possible from the residuals of the independence model applied to the original cross -tabulation (i. e. from the expected values within the calculation of the chi-square statistic. )

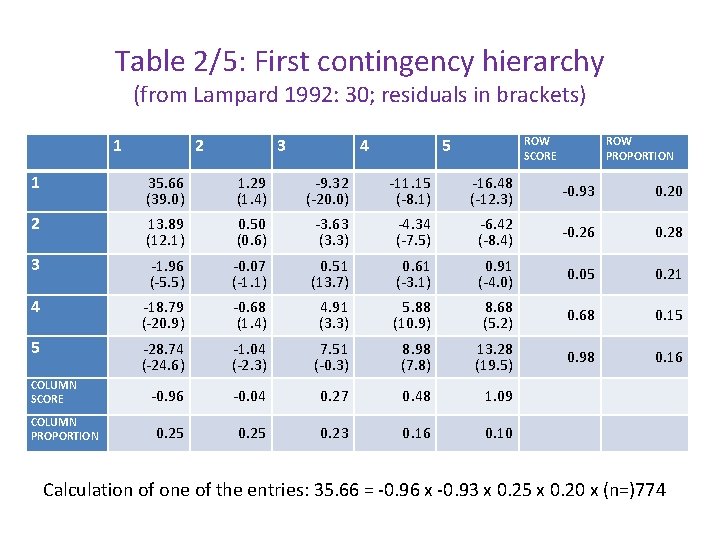

Table 2/5: First contingency hierarchy (from Lampard 1992: 30; residuals in brackets) 1 2 3 4 5 ROW SCORE ROW PROPORTION 1 35. 66 (39. 0) 1. 29 (1. 4) -9. 32 (-20. 0) -11. 15 (-8. 1) -16. 48 (-12. 3) -0. 93 0. 20 2 13. 89 (12. 1) 0. 50 (0. 6) -3. 63 (3. 3) -4. 34 (-7. 5) -6. 42 (-8. 4) -0. 26 0. 28 3 -1. 96 (-5. 5) -0. 07 (-1. 1) 0. 51 (13. 7) 0. 61 (-3. 1) 0. 91 (-4. 0) 0. 05 0. 21 4 -18. 79 (-20. 9) -0. 68 (1. 4) 4. 91 (3. 3) 5. 88 (10. 9) 8. 68 (5. 2) 0. 68 0. 15 5 -28. 74 (-24. 6) -1. 04 (-2. 3) 7. 51 (-0. 3) 8. 98 (7. 8) 13. 28 (19. 5) 0. 98 0. 16 -0. 96 -0. 04 0. 27 0. 48 1. 09 0. 25 0. 23 0. 16 0. 10 COLUMN SCORE COLUMN PROPORTION Calculation of one of the entries: 35. 66 = -0. 96 x -0. 93 x 0. 25 x 0. 20 x (n=)774

So what’s left? • Note that the five biggest discrepancies between the residuals and the contingency hierarchy are in the third row and/or third column; these are consequently the focus of the second contingency hierarchy. • However, the first contingency hierarchy accounts for 131. 6 of the original chi-square statistic of 153. 2 (i. e. 85. 9%), leaving only 21. 6 for the subsequent contingency hierarchies.

Warwick university sociology

Warwick university sociology Warwick sociology modules

Warwick sociology modules Warwick physics department

Warwick physics department 01926 600036

01926 600036 Cryer elevator uses

Cryer elevator uses The warwick model

The warwick model Leicester warwick medical school

Leicester warwick medical school Leicester warwick medical school

Leicester warwick medical school Edman tsang

Edman tsang Kerry pinny

Kerry pinny Business coach warwick

Business coach warwick Susan carruthers warwick

Susan carruthers warwick Warwick rudd

Warwick rudd Warwick bartlett

Warwick bartlett Warwick maths modules

Warwick maths modules